“A breathless eagerness in the audience…”

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, whom Leigh Hunt described as a “sweet faced young lady,” wrote the novel Frankenstein during her brief marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley, the British poet. Written partly as a Gothic horror story but also as recreation to while away dark winter evenings, Frankenstein was an enormous hit in its time, both as a novel and in stage adaptation. Louis Untermeyer has speculated that in terms of popular interest her work far exceeded that of Shelley. She was a naturally talented writer and had been reared in a lively household—her mother was a champion of women's rights and her father was William Godwin, the political philosopher.

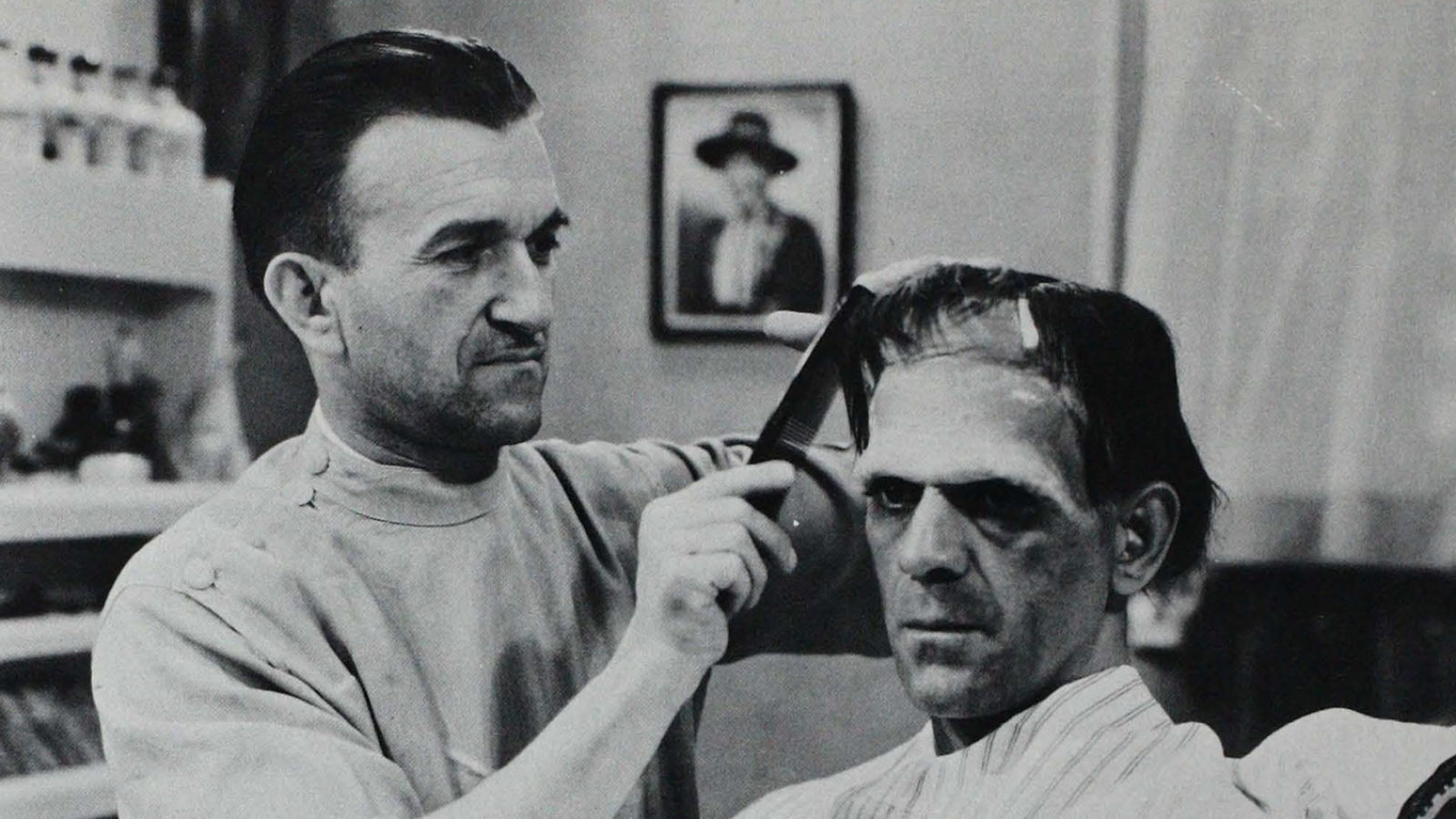

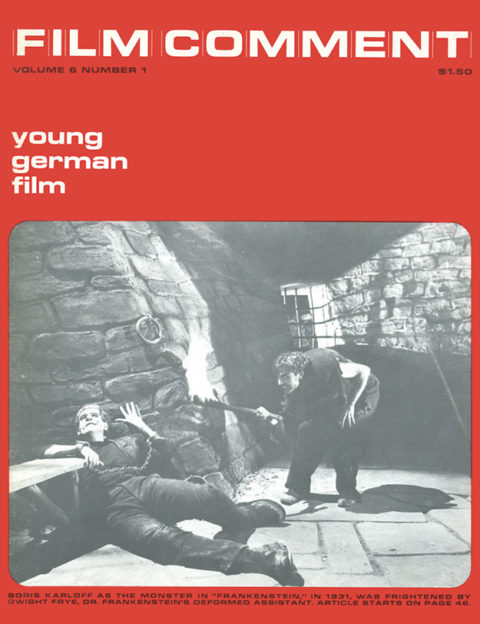

“It is doubtful whether Mr. Boris Karloff, with all the aids which cinematic technique can give him, looks any ghastlier or frightens any more people into fits than did T. P. Cooke,” writes historian Elizabeth Nitchie. Cooke was the foremost actor-interpreter of the role of the Monster, in Presumption, Or The Fate of Frankenstein, written by Richard Brinsley Peake.

Presumption was the first stage adaptation, in 1823, of Mary’s novel. A frequent visitor to the theater, she later saw her characters in various other adaptations, including burlesque and melodrama. In a letter to Hunt, she described the 1823 performances of Wallack as Dr. Frankenstein and of T. P. Cooke as the Monster—who was listed as ________ in the program:

But lo and behold! I found myself famous. “Frankenstein” had prodigious success as a drama, and was about to be repeated, for the twenty-third night, at the English Opera House. The playbill amused me extremely, for, in the list of dramatis personae, came “________, by Mr. T. Cooke;” this nameless mode of naming the unnamable is rather good . . . Wallack looked very well as Frankenstein. He is at the beginning full of hope and expectation. At the end of the first act thestage represents a room with a staircase leading to Frankenstein’s workshop; he goes to it, and you see his light at a small window, through which a frightened servant peeps, who runs off in terror when Frankenstein exclaims, “It lives.” Presently Frankenstein himself rushes in horror and trepidation from room, and, while still expressing his agony and terror, (“________”) throws down the door of the laboratory, leaps the staircase, and presents his unearthly and monstrous person on the stage. The story is not well managed, but Cooke played ________’s part extremely well; his seeking, as it were, for support; his trying to grasp at the sounds he heard; all, indeed, he does was well imagined and executed. I was much amused and it appeared to excite a breathless eagerness in the audience.

There was no copyright hindrance in 19th-century theater, and many hack dramatists and producers exploited Mary’s highly original characters and her mysterious melodrama. But at first the play was picketed by orthodox moralists opposed to Percy Shelley’s atheism and to the play’s central action—the creation by man of another creature, usurping a godlike function. Producer S.J. Arnold, in rebuttal, printed in the playbill the following statement—“The striking moral exhibited in this story, is the fatal consequence of that presumption which attempts to penetrate, beyond prescribed depths, into themysteries of nature.” The very title of the play—Presumption, Or The Fate of Frankenstein—emphasizes that moral, which has recurred endlessly since then, and in various forms in films, perhaps best in The Invisible Man. On a related theme, based on medieval Jewish legend, Paul Wegener’s The Golem (Germany, 1920, photographed by Karl Freund) showed the terrible consequences of creating a great monster, fashioned by a wise but heretical rabbi. Only Things to Come, from the H.G. Wells novel, directed by William Cameron Menzies in 1935, makes a total assault on nature’s mystery, arguing that Man must know it all.

Following the first adaptation of Mary’s novel, in 1823, four burlesques followed in rapid succession. Cooke again portrayed the Monster three years later in Paris. A British company then presented an English- language translation of that French version. Various melodramatic versions were done in the following years. There were annual revivals, in various forms, and as late as 1887 a burlesque was produced at The Gaiety, in London. Since the 1930’s, there have been several serious British stage versions, and in the U.S. five films, all with Boris Karloff, as well as several non-Karloff Frankenstein films.

As “creator” of the role of Monster, Cooke is described in a contemporary magazine as of green and yellow visage, watery and lack-luster eye, long-matted and straggling black locks, with blue, livid hue of arm and leg, shriveled complexion, lips straight and black, and a horrible ghastly grin. Although Wallack as Dr. Frankenstein was the star of the first adaptation, Cooke always stole the show and was much praised by critics of that period for his pantomime portrayal of the Monster’s awakening to sense impressions and his embryonic human sympathy—as intended in Mary’s novel. Described as “…thebeau ideal of that speechless and enormous excrescence of nature,” Cooke toured the provinces with the role and took it to Paris later.

The Monster has died in various ways on stage, depending upon the adaptation: by avalanche, thunderbolt, fire, Arctic storm, drowning, suicide by leaping from a crag, and by plunging into the volcano of Mt. Etna. So many characters in theParis version of the play died on stage that Le Journal de Paris remarked that it would be difficult to do more, unless one killed also the prompter and musicians. In an English stage production of 1933, the Monster was shot to death. In films, he has perished in ingenious ways, including extinction in a pool of burning sulphur.

Among the burlesques, the well-intentioned doctor was variously named Frankenstitch and Frankinsteam, and the Monster appeared as a hobgoblin, bailiff, dwarf and mechanical man. In one burlesque, the Monster’s death comes in “…an awful Avalanche of Earthenware, a Tremendous Shower of Starch, and an Overwhelming Explosion of Hair Powder.”

Aside from the unacknowledged imitations, about fifteen different versions of Mary’s novel were produced, variously farcical or musical or serious, over the span of one century, and some enjoyed long, prosperous runs. Sang one character in an 1849 production—“You must excuse a trifling deviation, from Mrs. Shelley’s marvelous narration…”

The scenarists for the first Frankenstein film, Garrett Fort and Francis Edward Faragoh (it was directed by James Whale in 1931), drew in part upon Peggy Webling’s 1927 stage adaptation, particularly in the famous incident, both tender and terrifying, of the flower and the little peasant girl, whom Karloff as the Monster kills. Certain elements in other stage versions are echoed in subsequent Frankenstein films, wherein the brain of a dead criminal, cut down from the gallows, is used to create the Monster.

Of course, the Monster far over-shadows the good doctor in having captured such public devotion for 140 years. He expresses our basic fascination with death and with an artificial creation of life-potentially a theme of tragic grandeur. Critics in the 1820’s, as now, have lamented such depraved public curiosity. But the Monster persistently has been re-born, or rather, re-manufactured, in film and theater, despite the critics. Mary Shelley, who created the Monster long ago, at theage of nineteen, would doubtlessly have loved Boris Karloff, now recently deceased. Of the various monsters, perhaps he was the monstrous-est monster of them all.