Not Buying It

History develops; art stands still.”—E.M. Forster

Movie lovers seem to have been gripped by fear for the fate of our beloved medium for almost as long as cinema has existed. If we’re particularly worried now, here at the beginning of the third decade of the weird 21st century, it’s probably because we’ve devalued, soiled, and decimated art, beauty, and nature at the hands of capital, and one can’t completely separate the state of cinema from the fate of the planet. As humans, we have expedited our own extinction via an industrial process that has been generally concurrent with the technological ascent, commercialization, and decline of the movies across the 20th century.

It would appear that the popular art form of the motion picture is in terrible shape. Yet the cloud of inevitability that hangs over the way we talk about movies and their destruction is probably as harmful to their cultural longevity as any rapid shift itself. This is not because I’m naïve enough to think that the threats to that culture aren’t alarmingly real, but because the outcomes of those feelings of inevitability can have detrimental effects rather than inspiring the proper reaction, which is, of course, resistance. Whether in our political system or the health of the arts, after all, capitulation is the worst response to feelings of helpless eventuality. It’s the response that leads to the over-corporatizing of festivals, the closing down of “niche” or “boutique” services, the conflation of whipped-up online fearmongering with “discussion,” and the shuttering of publications. There are facts, and there is rhetoric, and often in our fragile industry the two are confused.

Before going any further, here’s a short, inexhaustive catalog of what’s ailing the movies—or at least the American movie business—as we begin 2020. The studios have become a cohort of entirely risk-averse bottom-liners, resulting in an arsenal of franchise products aimed at the wallets of mostly teen boys, but also their infantilized parents, in a natural progression—or perhaps the endgame—of where the business has been headed since the mid-’70s. This sense of homogenization has been dangerously compounded by the fact that Disney is in the process of all but taking over the industry, its gut-busting portfolio including not only Pixar, Lucasfilm, and Marvel, but also, as of just last year, the studio no longer to be known as 20th Century Fox. At the same time, the streaming revolution has been ever so gradually monopolized by a handful of goliaths—Netflix and Apple, in addition to the Mouse House—desperate for subscribers to help them break even, churning out the kinds of mega-entertainments they hope can compete with (and one day replace) the big-screen experiences we once thrilled to. In related bad news for the health of a culturally and economically diverse society, in November 2019, the United States Justice Department moved to overturn the 1948 Paramount Decree, the court decision that split up the studios’ monopolies on U.S. film exhibition—a landmark in antitrust lawmaking and a bedrock historical point for anyone who took a film studies course over the past half-century. That postwar decision came at a time when television was beginning its march toward cultural domination; that the reverse is happening as we face the very real threat of streaming-service takeover says a lot about a political moment shaped by deregulation and corporate coddling. Understandably, it makes mainstream cinematic culture seem as dubious a prospect as it ever has in our lifetimes.

All that said—and not even taking into account the online arguments that so often make movies, born of nuance and collaboration, seem like prizefighters duking it out—why am I feeling that we’re heading into a good, maybe even inspiring moment in the history of the movies? Part of it is that through adversity comes triumph, yes, but more importantly, I think it has to do with the empowerment in recalibrating expectations—in treating the “inevitable” as a challenge rather than a reason to stop fighting. Money men saw the potential in cinema as a mass cultural leveler at least as far back as 1908, when ownership fights between the Edison Manufacturing Company and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company resulted in the competition-destroying Motion Picture Patents Company. But the battle to recoup the movies as art has been ever thus, and that battle remains stronger than those who wish to prognosticate its demise.

Susan Sontag wrote in her February 25, 1996 New York Times Magazine essay “The Decay of Cinema” that “the commercial cinema has settled for a policy of bloated, derivative film-making, a brazen combinatory or recombinatory art, in the hope of reproducing past successes.” That’s hard to deny, especially 24 years on, as is this: “The reduction of cinema to assaultive images, and the unprincipled manipulation of images (faster and faster cutting) to make them more attention-grabbing, has produced a disincarnated, lightweight cinema that doesn’t demand anyone’s full attention.” It’s become a common refrain, one that’s only grown louder and more prevalent, among those of us wary and weary of a cinema that often seems like a series of jolts from a joy buzzer. But the belief that rapid cutting and condensed visual storytelling will have some kind of stroboscopic, brain-melting effect on our dear children has a familiar ring to it, and has contributed to a lot of alarmism about Generation Z’s alleged lack of attention spans. (The perspicacious and patient students in the New School film studies class I taught this past fall proved such stereotypes to be categorically untrue.)

To decry the evils of a form based on sensation is to deny that it’s born of a technology that was itself born of the demands of modernity. Walter Benjamin wrote in 1939, “In a film, perception in the form of shocks was established as a formal principle. That which determines the rhythm of production on a conveyor belt is the basis of the rhythm of reception in the film.” The faster, bigger, louder principle that fuels everything from automotive actioners to “boys/girls behaving badly” comedies to children’s entertainments featuring CGI critters voiced by Emma Stone or Tony Hale is just the natural outgrowth of the rapid tempo and visual fragmentation that has been steadily expanding since the late 19th century; it’s just become more sleek and soulless through corporate commodification.

To bemoan film culture—and augur its demise—only by pointing to its crassest products is to do a disservice to an art form that has always only been as good as its outliers. Yet it’s easy to forget that individualized auteurs were always the outliers in an industry that boasted of them as its exemplars. When Sontag wrote “The Decay of Cinema,” she was coming off of a year that saw the release of such studio-financed films as Clint Eastwood’s The Bridges of Madison County, Spike Lee’s Clockers, Amy Heckerling’s Clueless, Tim Robbins’s Dead Man Walking, Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress, Michael Mann’s Heat, Jodie Foster’s Home for the Holidays, Oliver Stone’s Nixon, David Fincher’s Seven, Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls, Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, Gus Van Sant’s To Die For, Forest Whitaker’s Waiting to Exhale, and the first Pixar feature, Toy Story. And this isn’t even acknowledging the smaller-budgeted independents picked up and released by mini-majors that year, including Todd Haynes’s Safe, Wayne Wang’s Smoke, and Jim Jarmusch’s—infamously buried—Dead Man. On a personal note, 1995 was the year I first started writing about movies as a semiprofessional biweekly critic—though I was still a high schooler—for the Chelmsford Independent, my little town newspaper, which has since gone sadly syndicated. (Foster’s raucous, bravely queer-tinged family farce was my first published review, and thus remains a milestone.) Considering the core-shaking excitement I felt for a medium that I was only starting to comprehend—years before I’d find out who Tsai Ming-liang, Claire Denis, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul were and my love would be kindled all over again—I would have been incredulous if I had been told that one of our foremost cultural essayists believed that cinema was in its final stages. I imagine younger cinephiles who have thrilled in recent years to Atlantics, Uncut Gems, Midsommar, If Beale Street Could Talk, The Souvenir, The Human Surge, or this year’s miraculous Best Picture winner Parasite might feel the same way, regardless of where or how they saw them.

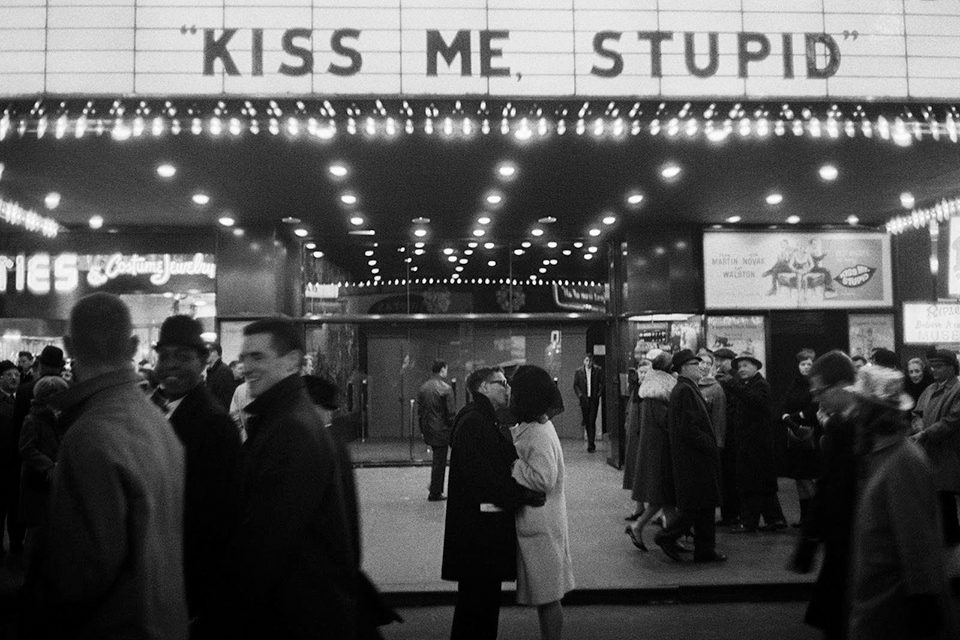

Courtesy of Joel Meyerowitz, Howard Greenberg Gallery

Martin Scorsese, whose thrilling, risky Universal production Casino was also released in ’95, wrote his own New York Times broadside just this past year, occasioned by perfectly reasonable comments he made about Marvel movies not being “cinema.” Sontag’s mourning for the loss of risk-taking, personalized studio productions persists in his essay, though the situation may appear a little more dire today: “In many places around this country and around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen. It’s a perilous time in film exhibition, and there are fewer independent theaters than ever. The equation has flipped and streaming has become the primary delivery system.” Couple this thought with the fact that Scorsese was at the same time acknowledging the release of his first film for streaming king Netflix, The Irishman—an exquisite, interiorized portrait of mortality and loss that seems designed to feel at every aching moment like the last of a certain kind of movie—and you’ve got a head-spinning moment in our culture, when the delivery system many see as heralding the doom of a traditional art form seems to be the only major studio actively upholding it. When Sontag concluded, “If cinema can be resurrected, it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love,” surely she couldn’t have imagined this, in which a media giant wields classical auteurism as a kind of brand-building tool.

Sontag’s essay has long read to me, and surely to many movie lovers of my generation, like a travel guide to a kind of Shangri-La, a place we never had and knew we never would have. We never had those overwhelming, transporting movie palaces for our commercial studio products; neither did we experience the advent of the new cinephilia of the ’60s and ’70s that emerged around the international new waves and allegedly made Antonioni, Bergman, and Bertolucci household names. What my generation had was the very clear dichotomy between VHS home-viewing and the experience of going to multiplexes, where we would watch films of generic shape but invigorating variety, in dark theaters with appreciative communal audiences—films shown on film. How could we ever have known that even that would soon be fading away? And what would it have mattered? Looking back, I am glad to still have the sense memory of being rapt, disturbed, and delighted in that magical November 1993 by both The Piano and A Perfect World at the now-demolished Showcase Cinemas in Lawrence, Massachusetts—but I also know that to look back and mourn for some lost paradise is to give in to the idea of cinema as a mere shadow of itself.

Self-congratulatory clip shows and highlight reels set to “As Time Goes By” have always tried to sell us on nostalgia as one of cinema’s primary ingredients, on the idea that its present is only as good as its past. The converse couldn’t be truer. If the long-necessary cultural shake-ups over the past few years around representation on screens and behind the scenes—in terms of race, gender, and queerness—have yet to begin bearing real fruit (cf. the American films and performances acknowledged during this year’s award season), the coalescing of a communal dialogue around these matters indicates the healthiest progression and reorientation of the medium I can recall in my lifetime. The same old clip reels simply won’t do, but neither will feints at diversity for its own sake. Even if American film feels in finer fettle in the wake of Get Out, Little Women, and Moonlight, it must be remembered that Hollywood has never been able to make good on its righteous successes, has never made any promises, and has never been able to capitalize on William Goldman’s “nobody knows anything” admittance to benefit itself or its viewers. Parasite won’t beget more movies like Parasite, just more movies that are Parasite—a remake miniseries is in the works; after all, it’s already been tested. We can’t depend on the studios, especially in their current state; aside from turgid biopics of safely dead political figures, “doing the right thing” just isn’t their style. What we as cinephiles can continue to rely on is the same thing we’ve always had, and which will never go out of fashion: our passion. Our love, our need, our exultant advocacy for films, not products.

Who’s financing good movies is one thing—and something most of us have no control over—but just as important to note is who’s watching them, who’s talking about them, and who’s safeguarding their legacy. I don’t use the word “safeguard” as a way of sanctifying the gatekeepers of what has traditionally been an exclusionary business, but as a term for ensuring the intellectual health of the culture that’s currently set in place to protect the art. Independent traveling exhibition setups for films of uncommon shape and form, such as Argentine filmmaker Mariano Llinás’s Sociedad de Exhibidores Transhumantes; itinerant showcases like Acropolis Cinema, which runs Locarno in Los Angeles; and dedicated specialty streaming services like MUBI will prove increasingly invaluable. So will publications like Film Comment, which continue, against all perceived odds, to grow a readership and fan base despite their steadfast devotion to art, form, and substance rather than the drummed-up PR narratives and hot-new-thing stories that have taken over much of what’s called entertainment journalism. Meanwhile, the larger nonprofit arts institutions—festivals, museums, and devoted organizations like the one that publishes the magazine you’re currently holding in your hands—will become even more important for the continuing education and understanding of cinema as the gap grows ever larger between the art and the commercial enterprises that purport to buoy it, but in reality threaten to swallow it up.

To give in to the demands of capital does not reflect an inevitability; it proves a lack of imagination. It’s imperative that these institutions hold up these traditions: of championing challenging cinema, of maintaining independence from the companies that are using that cinema as a belt-notch for niche bona fides, of staving off what they believe to be inexorable tide-turning in an industry in which, after all, nobody knows anything. The cinematic world that true film lovers have long hoped for—one of rich diversity and challenging form—is only actually possible if we think of movies as works of art; as expressions of interior states; as reflections of genuine pain or elation; as redefined, reconfigured interpretations of a world that, ever since film was invented, seems like it has been spinning out of control.

The hard-won appreciation of cinema as something that is as worthy of consideration as paintings or poetry was always fought from the sidelines; it’s the adoration of cinephiles, rather than the whims of the casual weekend moviegoer, that’s made its longevity possible. Does that sound snobbish? Good, own that; remember that those who reject the idea of challenging art—or at least forms of expression not entirely reliant on brand management—are both revealing their threatened nature and trying to sell you on something else that was already sold to them. To remind readers of the still-minority opinion of cinema as an art form, Scorsese mentions Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising in the same breath as Bergman’s Persona and Donen and Kelly’s It’s Always Fair Weather, cleverly and crucially dissolving boundaries and hierarchies, and reiterating that film will only ever be as dynamic as its avant-garde, as healthy as its art-house cinema, as imaginative as its best studio endeavors. After all, at the same time that moviegoers were enjoying Executive Suite or crying over Old Yeller at the Paramount or the Oriental, curious adventurers were seeking out Rashomon at the Brattle, while devotees at Cinema 16 were being treated to Agnès Varda’s L’Opéra mouffe or Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour. The survival of the movies may, finally, depend on considering them as one large entity rather than separate, sectioned-off categories, of “right” and “wrong” types. If we think of the movies as different forms jousting to the death, we already know which side is going to win.

Three years after Sontag proclaimed cinema’s imminent demise, a new round of articles claiming a more literal death of film began springing up—most memorably and presciently by Godfrey Cheshire in the New York Press—this time wedded to the digital transition that was beginning to take hold in movie production and projection. Things were changing; it was inevitable, yet still abstract. At this time, I was a cinema studies undergrad at NYU, and often serving on crews for my friends’ film productions, all of which were still being shot on pricey 16mm or 35mm stock and edited on Steenbeck flatbeds. The thought of reapplying everything that had been taught about shooting on film to digital was barely even a consideration. Yet what I remember first and foremost is the thrill I felt around two events at the break of the millennium: the release of Varda’s The Gleaners and I, which foregrounded its own lightweight digital equipment and heralded a new diaristic mode of cinema made possible by its portability; and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (see p. 74), which utilized the smudgy, bleary aesthetic of low-grade video to visualize a persistently racist America as a diseased dystopia. Varda’s film was embraced, Lee’s was rejected, but both were, to anyone paying attention, clearly exciting works whose power came in large part from the way they wielded new technologies. The thrill of this transitional moment still reverberates for me. The form that movies have taken in the 20 years since then already feels radically different. Yet their shape hasn’t shifted as significantly as it one day will. Cinema’s progression will not be in a straight line, but it will be a progression. It’s inevitable. It will regenerate as long as there are people—and a planet—to sustain it, and as long as those tasked with its stewardship treat it like it’s the precious form it is, rather than a commodity.

Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer & Now & Then; and the author of Terence Davies (University of Illinois Press).