Night Gallery

The footage of David Lynch blinking back tears during the standing ovation at the Cannes premiere of the first two episodes of Twin Peaks: The Return is an obvious contender for wholesome meme of the year. But more than vindication for a man who entered the “booed at Cannes” canon with Fire Walk with Me 25 years earlier or a break from his mystical Eagle Scout routine, the tears spoke to something deeper yet plainly obvious, as they often do in Lynchland. It was one of the most notable times during his 50-year career that there wasn’t lag time between the work and the appreciation.

For someone who has left such an indelible mark on film history, Lynch has made just 10 feature films in 40-plus years. During the sizable gaps between his movies—which occurred more often than not because they were skewered by critics and ignored by audiences—Lynch paid the bills with odd jobs, be it a paper route (during and immediately following the interminable making of Eraserhead) or an Alka-Seltzer Plus commercial (between Fire Walk with Me and Lost Highway), and continued making paintings, sculpture, furniture, music (dance pop, industrial, surf rock, or all three at once), Flash animation, and web video shorts. Lynch is an artist who only becomes more himself as time passes, and his expressions in other media are inseparable from his films; his initial foray into filmmaking—1967’s Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), made while he was still a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts—was the result of his desire to make his paintings move. Why his cross-media output isn’t usually considered as a whole speaks to the richness of his films, the isolated nature of the art world, and the lack of film writers who are familiar or comfortable enough with art to think that way.

Despite its multimillion-dollar budget and cavalcade of musicians, stars, and “stars,” Twin Peaks: The Return is a moving image work that even more closely resembles the textures of his efforts in the plastic arts than the backlot nightmares of Inland Empire (2006). The first two episodes—more than worthy of that standing ovation—hint at the geographic, thematic, and visual expansiveness of the rest of the season. Much of the iconography of the original Twin Peaks (the Black Lodge) remains, and many of its classic elements have evolved (“the Arm,” the room above the convenience store), but there are also already unexpected images that instantly match their power: a twisted corpse with an anguished head that doesn’t match (a mix of Francis Bacon’s paintings and Marcel Duchamp’s The Illuminating Glass), a high-security room in Manhattan where a twentysomething kid watches a glass box (one of many metatextual nods to how people watch Twin Peaks), and Dr. Amp (formerly Dr. Jacoby), an Alex Jones–esque vlogger spray-painting some shovels gold with an elaborate, homemade device in his backyard, to hawk as merch.

This last image, which is our first vision of the town of Twin Peaks, is somewhat autobiographical. Dr. Amp’s artisanal production and choice of object reflects Lynch’s own home-studio methods and obsessions with painting certain tools or appliances, like telephones in “Hello” (2012) and telephone (undated), or the self-explanatory TV BBQ (2009). And whatever Phillip Jeffries (originally played by David Bowie in Fire Walk with Me) has gotten himself into looks like something that manufactures large quantities of tea or food for mass consumption—both a piece of heavy factory machinery and something you’d heat up a cuppa in.

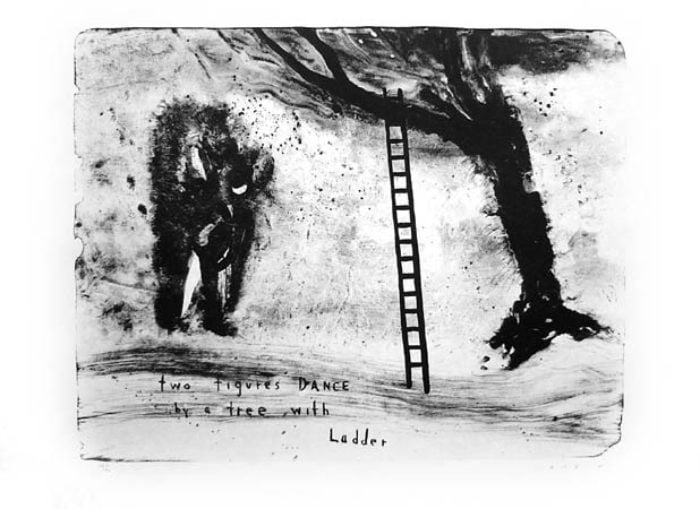

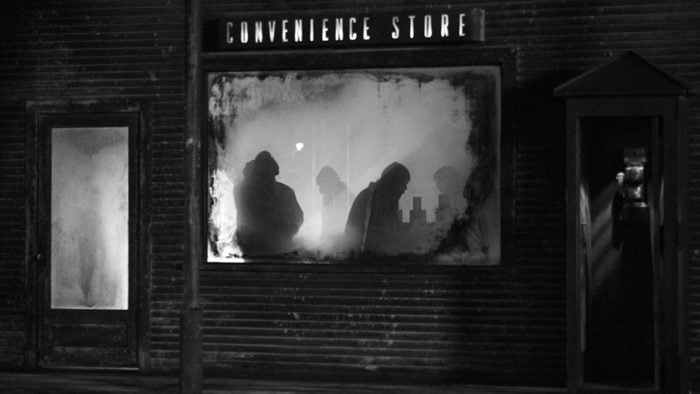

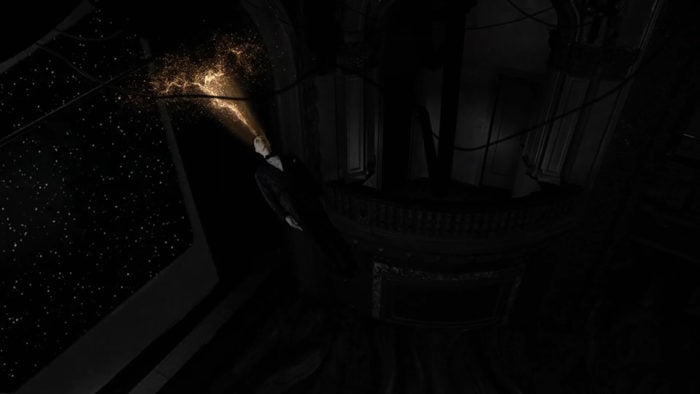

This crude and homemade ethos runs throughout many of the special effects in The Return, be it the convenience store (which is intercut with a scale model of it, punctuated with cherry-bomb-like explosions) in episode 8 or the sudden flash that takes Richard Horne’s life in episode 16. Rather than being clumsy, these effects have that same uncanny power of the baby from Eraserhead—an impossible nightmare that’s somehow animate, organic, and pissed off. Many of the show’s visual effects have a rough-hewn, lo-fi quality to them, such as when Cooper is ejected from the Black Lodge and falls through space, flattened like a Tex Avery character rolled over by a paving machine, splatting and then slowly sinking into that (still unexplained) glass box in Manhattan. The texture of his voyage finds its twin in the raised, lumpy canvas of Lynch’s A Figure Witnessing the Orchestration of Time (1990), in which a canary-colored figure begins to fuse with the darkened background, its head entrapped in a miniature wire fence while a burst of light and fire twists out of a triangular mountain. Such abstracted figures (which are often barely discernible as human) run throughout much of Lynch’s paintings and drawings, anguishing among raised brushstrokes, as in 1983’s Nihilistic Delusion. These figures and crudely realized special effects are carefully fabricated accidents of nature, things that follow the contours of feeling and intuition rather than linear cause-and-effect relationships. The woodsmen, Bob, and Bad Cooper’s automatons of evil could very easily be the all-black figures from works like Man Makes Crying Man (2012) or Two Figures Dance by a Tree with Ladder (2007).

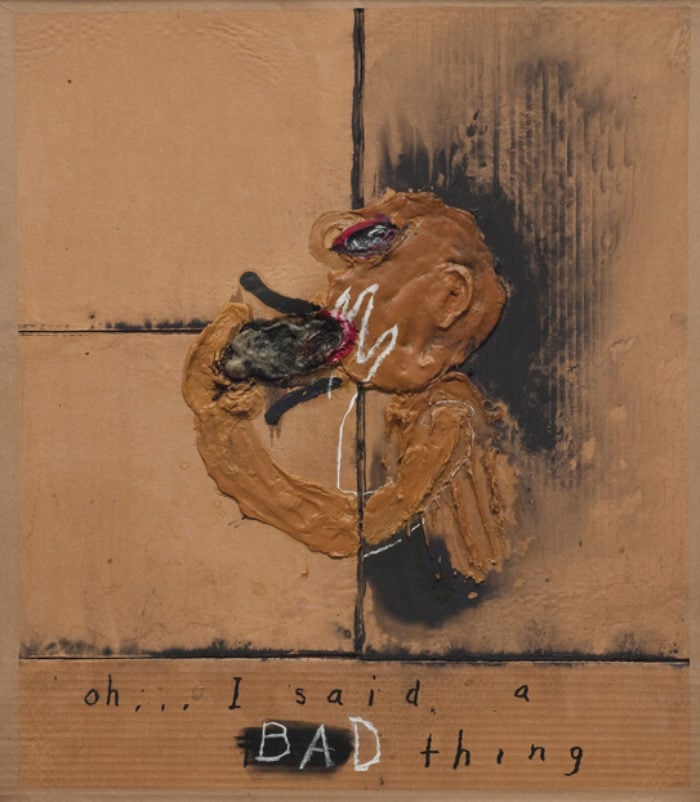

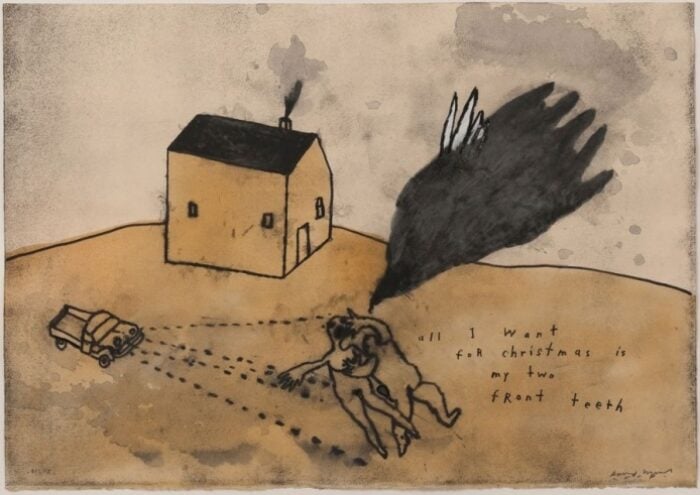

The more elegant VFX for The Return were created by the French effects company BUF (who also did the VFX for Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void), such as Agent Cooper’s attempt to take Laura Palmer away from Leo and Jacques’s cabin in the penultimate episode. But even the fantasias of episode eight—a radioactive reimagining of the stargate sequence of Kubrick’s 2001 and a creation myth of the Twin Peaks universe—are informed by motifs found in Lynch’s art. The creation/release of Bob during the atomic bomb test on July 16, 1945, offers a variation on the blobs emerging from (or descending into) figures’ heads in paintings like I See My Love (2012), All I Want for Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth (2012), or even Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times). The horrifying bug that crawls into the sleeping girl’s mouth at the end of this episode is echoed in Oh… I Said a Bad Thing (2009), save for the fact that the figure here is consciously stuffing the winged insect down its gullet. The transference of good and bad energies is a theme that runs throughout many of Lynch’s narratives, from Blue Velvet (1986) to Lost Highway (1996). Aside from bugs or mushroom clouds, the movement of these energies is literalized in The Return during episode six, when, after Richard Horne’s traumatic hit-and-run, Carl Rodd witnesses a translucent green mass exiting the dead boy’s body, which then disappears into some power lines. Methodical Peaks fans will also note the number on the power line’s pole, and how the scene is almost identical to one at the Fat Trout trailer park in Fire Walk with Me—except then no one could see the energy.

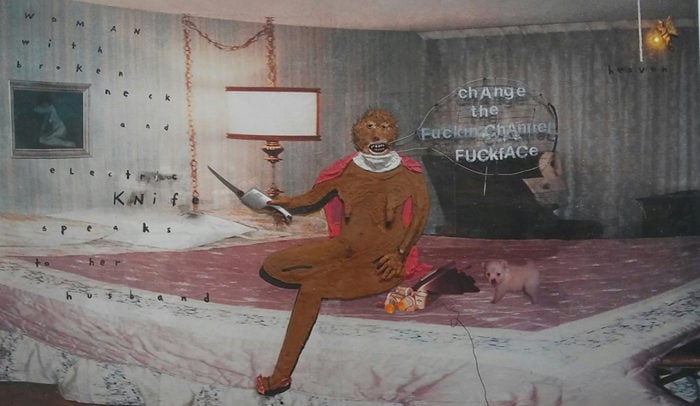

Despite the multiple narrative or casting connections to Fire Walk with Me, there is, thankfully, a lot of mystery left in The Return, in large part thanks to the familiar but never nostalgic occultation of Lynch’s visuals. (A Reddit user suggested that Judy is actually jiao-dai, which is the Chinese verb for “explain.”) The raw, rubber-glove-punching showdown between Good and Evil at the Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Station in the second-to-last episode employs the wonky spatial dynamics and incongruous objects in mixed media canvases like I Burn Pinecone (2009) or Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface (2008-9), and is about as illusively clear. The worlds that Lynch creates—on his canvases or for television—are very much like our own, the ugliness and disorder on or very near the surface rather than safely underneath it. In Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface, a nude woman sits on a bed facing us while brandishing a knife. We know she wants us to change the channel, right now—but why, and who are we to her? Are we a client or a lover? Is this a hotel, our marital suite, or a tract-house bedroom? Why is “heaven” labeled with a white skyward arrow? Well, who wants to know, really?

Closer Look: Showtime will release Twin Peaks: The Return on DVD and Blu-ray on December 5.