Dersu Uzala

Akira Kurosawa’s favorite directors are Ford, Wyler, Capra, and Antonioni. One of his pet recollections is a meeting with Ford in London: the American director sent the Japanese director chrysanthemums “and treated me just like his own son.” Dersu Uzala (★★★★) is Kurosawa’s most Fordian picture since Yojimbo (1961) and seemed the only new film in this year’s festival to be marked by a breath of greatness.

The Japanese-Russian co-production, set in Siberia, begins in 1911 when an army captain makes a pilmigrage to the grave of a friend. The rest is flashback to this friendship, begun when the captain, assigned to a topographic survey, encountered the old trapper who became his guide. Dersu lives in total harmony with the elements and converses with them—fire, water, wind—“All are men because they were alive.” When stalked by a tiger, he reasons with the animal: “Why are you following us? There is room in the forest for both of us.” The tiger retreats.

The two men meet again years later and the captain persuades the ailing Dersu to come to town and settle with the captain’s family. Dersu cannot adapt to civilization and returns to the forest where he is murdered for the rifle the captain had given him as a parting gift.

The film’s finest passage occurs when the hunter and the captain are stranded on a frozen lake—a harrowing, spooky-gorgeous spectacle of supernatural realism. During the seventeen-day festival there was no performance as memorable as that of Maxim Munzuk—who looks like a benign wizened Nibelung—as Dersu Uzala.

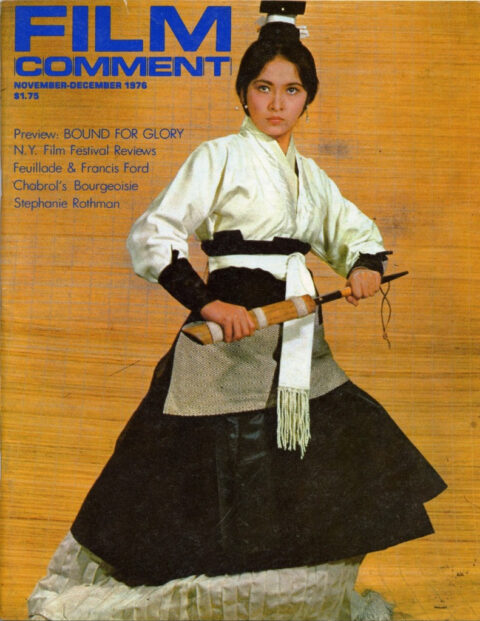

Touch of Zen

Until this festival my experience with Hong Kong cinema had been limited to a few minor products from the Run Run Shaw Factory. The splendor of Touch of Zen (★★★) came as a major surprise. King Hu—its director, executive producer, scenarist, editor, and set and costume designer—is not any old one-man band: he is skilled at each instrument.

Hu was born in Peking in 1931, in 1949 moved to Hong Kong where he worked as an actor and screenwriter. He was with Shaw for several years, then formed his own production company.

With the first shots of Zen we are plunged into a nature marked by eerie majesty—close-ups and spiders seizing their prey in huge webs, mountains in the background, low-rolling fog which never seems to dissipate: Ching-lu fort, a haunted place in fourteenth-century China.

The film’s first hour, though of startling visual elegance, plods a bit in the process of getting some low comedy out of the way and clarifying the lines of combat. The center of interest (at least at the start) is a young artist who lives with his dunderhead Ma, and is in awed admiration of the mysterious Miss Yang who has moved into the Old Dark House next door. She is a fugitive, sought by the forces of a malevolent warlord, Eunuch Wei—he has her father murdered, just one of his twenty-four crimes! Yang is now allied to a party of no-nonsense monks, all of them masters of defensive Kung fu.

The last two hours sweep us through a series of stylized battle scenes (shot at imposing Taiwan and Hong Kong locations) which are breathtaking and refreshingly free of gory mayhem. The movement during these magical clashes in forest, on mountains, and at riversides are derived from the choreographic style of the Peking Opera. Frisky Hsu Fend is great shakes as the whirling, twirling, high-vaulting heroine, and Roy Chiao Hung an interesting pillar of solidity as the Buddhist monk who bleeds gold when wounded.

King Hu was the revelation of this year’s festival. When do we get to see The Fate of Lee Khan and Valiant Ones?

Ossessione

“Golden Oldie” choices this year could not be disputed: Renoir’s Nana (1926) and Visconti’s Ossessione (1942). The festival program calls Ossessione (★★★) the “first neo-realist film,” and while this is hardly the truth, it is the first film of one of the key directors of our time.

Although Visconti was inspired by Verga and the verismo school (as were some of the neo-realists later—the first neo-realist film was Rossellini’s Open City, released in 1945), mementoes of late Thirties French cinema, in particular Carné and Renoir, are omnipresent in Ossessione. It was Renoir who suggested The Postman Always Rings Twice to him as a possible subject. The Renoir influence is most evident in the way the characters are related to landscape. The opening sequence—a long tracking shot ending in front of the gas station with the introduction of Gino (Massimo Girotti) descending from a truck into the bleak Po Valley boondocks—is handled with a simple uncluttered maestri unfortunately absent from later Visconti works.

The raw warm poetry of Ossessione has nothing to do with neo-realism; the film is unencumbered by ideology and political commitment, two trademarks of that school. This unique picture fits snuggly into no school. Gino has always seemed to me closer to a character in a Pasolini story than to any protagonist in other Visconti films. Odd, then, that it was at Saló that Ossessione’s negative was destroyed by the Italian “government.”

Story of Sin

Borowczyk’s Story of Sin (★★★) is claustrophobic hot-house cinema at its busiest. Hand-held cameras burry through murky apartments filled with endless corridors and fin-de-siècle bric-a-brac in a frantic rush to catch up with the heroine’s breakneck amour fou for an anthropologist-lodger as her love leads her to degradation, prostitution, infanticide, adulticide. The skeletal support of Boro’s art-nouveau Stations of the Cross is relatively simple, but it all works out in terms of more convoluted plotting per square millimeter of film than anywhere in recent memory. Strands of Adele H., of Lola Montès, of Pandora’s Box, lie strewn here and there. There may be less than meets the eye, but the eye is met with a great deal. Even if Sin is nothing more than Gran Guignol garni, I want to see it again for the pleasure of finding out.

Cadaveri eccellenti

Francesco Rosi’s Cadaveri eccellenti (★) is a glum threnody of fashionable paranoia, a commentary on the confused political situation in Italy, although it takes place in never-name land. What should be gripping gets quickly embalmed by the production’s soigné aestheticism. The last sequence—murders in slow-motion (for a change), investigator Lino Ventura gunned down in a museum, under the cold gaze of antique statuary—is a final empty stylistic gesture and mere piss-elegance. I wouldn’t give up on Rosi, though, who did, in C’ERA UNA VOLTA (1967; in the U.S., MORE THAN A MIRACLE), give us one of the most ravishing Italian films ever made.

Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (★★★), Alain Tanner’s best film, is a (sort of) Socialist You Can’t Take It with You populated by (mostly) Swiss post-1968 (semi) dropouts. No standard plot line, just eight persons wandering into each other’s lives and eventually forming a loose but vital community. Their alienation is channeled into nervous verbal energy, winning, bright, free from cant. Humanisme sans le schmalz. I took everyone to heat, especially bedraggled Miou-Miou, the supermarket cashier, and her friend, old Charles, beautifully underplayed by mournful, bleary-eyed Raymond Bussière, veteran of many Carné, Clouzot and René Clair films.

Marcel Ophuls’ The Memory of Justice (★★) examines German war guilt, as judged at Nuremberg, through the muddy prisms of Dresden, Hiroshima, Algeria, Vietnam. At five hours running time, with nearly fifty interviews, there is something for nearly everyone here, except for those who require easy answers. But as hour succeeded hour and interview was intercut with interview, a numbing Chinese box effect took over. I was grateful for what I found in some of the boxes, and shall not soon forget Johanna Kortner, simply and with great restraint, relating her return to Germany after the war, or the extraordinary strength and beauty in Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier’s face.

A lengthy interview with Albert Speer (arguably the most complex and fascinating major figure of the Third Reich) should have been of great interest. But the voice-over technique used in the version released by Paramount in this country put a wall between me and Ophuls’ film. I realize that, in a “talking head” picture, the alternative would be a glut of subtitles. Voice-over, however, is just genteel dubbing, and even more infuriating than bad dubbing. Looking at Speer, hearing him start a sentence in German, then having his voice suddenly replaced by stodgy English tones droning lines apparently read from a paper—it made me feel the man was having his soul stolen in front of my eyes. If not a crime against humanity like the bombing of Dresden, voice-over is an aesthetic misdemeanor which mars the film as a “document.” Curiously, Hitler is the only non-English speaker in The Memory of Justice who does not get the treatment.

Harlan County U.S.A.

The single feature-film world premiere at the festival was that of Harlan County U.S.A. (★★), mostly an account of the thirteen-month strike (1973-74) at Brookside, Kentucky. Few documentaries rivet you to your seat; this one does. The guts it took to make are up there on the screen, in the footage shot by director Barbara Kopple and cameraman Hart Perry during the violent encounters between scabs (mostly KKK members) and strikers. It is obvious that Kopple’s rapport with the miners’ wives was extremely close; the women all come through strongly, especially Lois Scott, the Jane Darwell earth mother of Harlan who totes a gun in her cleavage. This is a partisan film, far from flawlessly made. Watching it, one becomes a partisan of the miners of Harlan County. I wish it wide distribution.

The Middleman

Satyajit Ray’s The Middleman (★) is a predictable tale, set in Calcutta, concerning a young Brahmin who has just been graduated from the University and cannot find a “proper job.” He becomes a robber and enters the corrupt world of wheeling and dealing where his work soon involves pimping. There are lively near-Dickensian passages in the business sequences of the picture, especially those featuring Rabi Ghosh, a wonderful actor who portrays the “public relations” man who becomes the Brahmin’s mentor in petty capitalism. But the burden falls on Pradip Mukherjee, a drab performer whose loss of innocence is uninvolving.

The Strongman Ferdinand

Alexander Kluge’s The Strongman Ferdinand (★) is a sweet-and-sour spoof at the expense of West Germany’s mania for law and order. One-dimensional skits, however sympathetic and intelligent, not so easily compose a satisfactory feature film. The director of Abschied von gestern is capable of more than this.

Serail

Are we in for a devouring house cycle? Anyone with time and patience to spare who desires to compare a bad commercial crowd-pleasing film with a bad “new narrative” crowd-displeasing film—both jerry-built on similar farfetched premises—should rush to Dan Curtis’s BURNT OFFERINGS, then truck on down to Eduardo de Gregorio’s Serail (★). An exceedingly favorable, dead-serious review of the latter appeared I the June 1976 issue of the French magazine Cinématogrpahe, under the signature of Pierre Maraval. Maraval states that De Gregorio’s film is like a vaginal cramp. I have never been seized with one of those, but I have experienced Serail, and although this is not a favorable notice, I am willing to let it got at that: Serail is a vaginal cramp.

Duelle

De Gregroio collaborated on the screenplay of Jacques Rivette’s Duelle (★). The script is a model of abject silliness. Myths, fairy tales are pointless—even for children—unless a minimum of resonance is struck. This “non-existent myth” about the struggles of a moon and a sun goddess for a diamond talisman will not yield to any amount of disambiguation. The face behind the mask is not there (at the press conference, Rivette admitted he hadn’t a clue as to what this film was about), and the mask itself is not worth two hours of scrutiny, in spite of some stylish tracking shots.

Those who doubt that a fanciful fairy tale concerning the loss and recovery of a magic talisman can be the basis of a deeply moving work of art should refer to von Hofmannstahl’s libretto for Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten. Duelle is the sort of bad bad movie which gives good bad movies a bad name. Wild horses mounted by Jonathan Rosenbaum could not get me back to see it again.

Die Marquise von O

Die Marquise von O… did not cry out to be made into a movie. Had it done so, I wish it had shrieked in Buñuel’s direction and been answered. Eric Rohmer’s interpretation (★) of Kleist’s tart tall tale pretends to literalness it does not achieve, and is too “pleasant” by half. Kleist is not a pleasant writer. This picture, all gussied up into stage tableaux, looks like a Goethe House Gala performed in Bloomingdale’s Show Rooms.

In the vital role of the Russian Count, Bruno Ganz is a disaster incarnate, a silly bumpkin played for facile sympathy, rather than Keist’s complex hero, capable of assuming his actions with brio.

Why this film? At his press conference, Rohmer said that with his modern tales finished, he felt a desire to return to the past. He is currently planning a picture set I the Middle Ages; after that there will be one in Classical Antiquity—perhpas one set even further back…Ma nuit chez le brontosaurus is bound to be a moral gas.

Small Change

Truffaut’s Small Change (★) is a negligible opus about kids. Corny, cutesy, dull. The subtitles written by Helen Scott for Truffaut seemed awkward and illiterate. Why? The lady speaks excellent French and English. Why are subtitle so lousy? Those for Duelle were too large and too bright, distracting from the image; the titles for Serail—credited to August Films—were ridiculously large and really ugly, full of misspellings and mistranslations, one of which totally botched the last line of dialogue, and important clue to what the film thought it was about; Jan Dawson’s good titles for Ferdinand were sabotaged by dozens of misspellings; The Middleman’s titles were scrappy and ungrammatical; those for Story of Sin were cryptic gobbledygook; the subtitles for Zen informed us that the hero’s mother was thirty years old. Bully for he, her son was also thirty!