Autumn of the Patriarchs

This year’s New York Film Festival, the 41st, seemed to mark a changing of the guard: perhaps by happenstance, elder statesmen such as Godard, Rohmer, and Oliveira were not in evidence, moving Young Turks like Lars von Trier and Gus Van Sant into the front rank. To be sure, Claude Chabrol turned up with the suave if inconsequential The Flower of Evil, and Clint Eastwood scored a triumph with Mystic River. But if one had hoped to find in Lester James Peries, the 84-year old Ceylonese director of Mansion by the Lake, an undiscovered Asian master on the order of Im Kwon-taek, this disappointing clunker turned out to have more affinities with Ed Wood, as inept actors hopelessly stood around waiting to spout shrill back-story dialogue. (Noël Burch would have loved the absence of match cuts.) No, this festival seemed shaded more by filial contemplations of the world our fathers made, and the internal struggle between killing or sheltering the patriarch—a dialectic exemplified by Errol Morris’s noble study of Robert McNamara, The Fog of War, which probed the limits of a human being’s capacity to understand himself in the context of history.

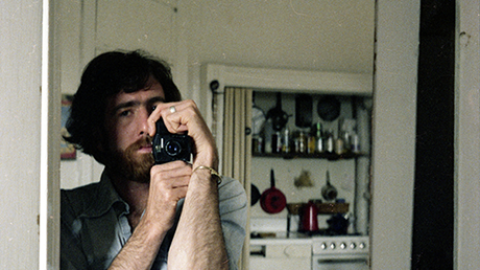

A fascinating counterpoint to Morris’s investigation was fellow Cambridge filmmaker Ross McElwee’s far gentler but equally thoughtful essay-film Bright Leaves, his best since Sherman’s March. McElwee has long engaged in a comic, rearguard action of propping up the patriarchy, and in this case he extends the defense upward to his grandfather and downward to himself, vis-à-vis his son. Ostensibly focusing on his family’s undervalued role in developing the North Carolina tobacco industry, the filmmaker meanders with playful digressiveness from the harmful effects of cigarettes to Patricia Neal’s affair with Gary Cooper, from swimming the English Channel to melodrama versus cinema vérité. The point is to hang out with the reflective McElwee, sharing his homesick, Zen-like pleasure at watching the world (especially the South), and his rueful anxiety at trying to parse its meaning. “Only from unnecessary things in art can you expect something unexpected,” the film theorist Vlada Petric, interviewed here, offers his ex-colleague, who obviously takes the advice to heart.

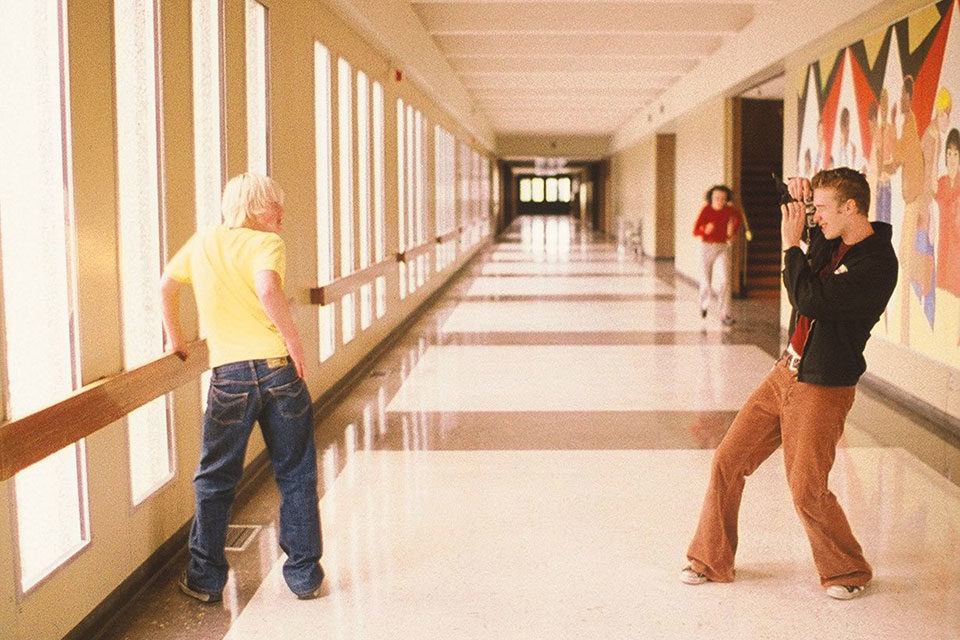

Marco Bellocchio takes the opposite tack, in Good Morning, Night, by eliminating any scrap of the “unnecessary” and bearing down on the inevitable with virtuoso ferocity. In this reenactment of the kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigade, the solemn young parricides cannot even allow themselves the gleeful personal satisfaction that might come with Killing the Father, so self-deluded are they in their belief in imminent revolution. Bellocchio refrains from developing the terrorist cell members into individual characters (probably a mistake), instead concentrating all his compassion on the one woman in the group, who, though fairly inarticulate, is allowed to express scruples through her dream-life. Moro himself is sympathetically portrayed, though Bellocchio indicts the Pope and the politicos for allowing the President to die—more so, perhaps, than he does the Red Brigade. Whatever his political point, Bellocchio’s filmmaking skills have never been more solidly employed. He brings Bressonian rigor to the process of confinement, tinged with swelling moments of Viscontian operatics in the score, making for an intriguing if ultimately too narrow treatment of the subject, which calls for a little more insight. Trying to understand the mind of the killer—or, in broader terms, the mentality behind the senseless shedding of human life—was a recurrent preoccupation of a number of films here. The problem is that murder, like suicide, is at once so over—and under-determined an act that trying to dramatize the supposed motivations or timelines leading up to it can seem arbitrary at best. Perhaps for this reason, I was more persuaded by the killers in the documentaries than in the dramatic features. In Rithy Panh’s amazing S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, seeing the actual guards return to the scene of their crimes and express a chilling combination of self-pity, regret, pride, and selective recall, watching them re-create their wakeup procedures in the cells, was shocking but utterly convincing. (It helped that the film has an austere formal intelligence as well as a sledgehammer power.) Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, based on the Columbine High School shootings, had formal elegance to spare, and I loved everything about it—except for the parts spent with the killers: getting ready for their rampage by watching Nazi footage on television, kissing in the shower, and taking naps. They seemed entirely too Warhol-lax for their Götterdämmerung. Similarly, I could believe Robert McNamara’s on-camera confession that firebombing Tokyo possibly constituted a war crime, but had a harder time buying as killers the subdued, colorless ideologues in the Bellocchio (though that may have been his point). As for Sebastian Dehnhardt’s 156-minute Stalingrad, a conventionally made PBS-type documentary, you watch millions being slaughtered in the bloodiest battle of WWII, at the behest of two mad dictators, Hitler and Stalin, and feel alternately moved and numb by the glut of information.

Elephant

A small gem, Since Otar Left, about three generations of Georgian women waiting for their beloved male relative who will never return, was distinguished by its patient observation of family dynamics and a stunning triumvirate of performances, led by Esther Gorinton as the intellectual, Francophile grandmother. Julie Bertuccelli’s fiction debut has a documentary look in exteriors and a wry regard for everyday rituals, cruelties, and coping mechanisms. Everyone lies; everyone speaks her mind sooner or later. To label this film “humanistic” or “Chekhovian” is correct but shorthand; it does not get at the mysterious skill that draws us into these women’s lives and convinces us that we are watching something truthful.

The Austrian-made Free Radicals was another strong (if muddled) film by a young woman director, Barbara Albert. This ensemble drama follows a group of city people tied together, almost without their knowledge, by catastrophe and grief. Albert imposes one miserable rejection, embarrassing humiliation, or suicide threat after another on these poor neurotics, until her plotting verges on the sadistic; then she lets in little stabs of happiness, or at least hope. Characters go on a TV show called “Forgive Me” to say they’re sorry, or enact their traumas in group therapy, in scenes both satiric and sympathetic. The film is overstuffed with bits of observation, and excessively willed at times, but there is a true personal vision underneath it, and a remarkably assured technique, which moves from detached to subjective with startling ease.

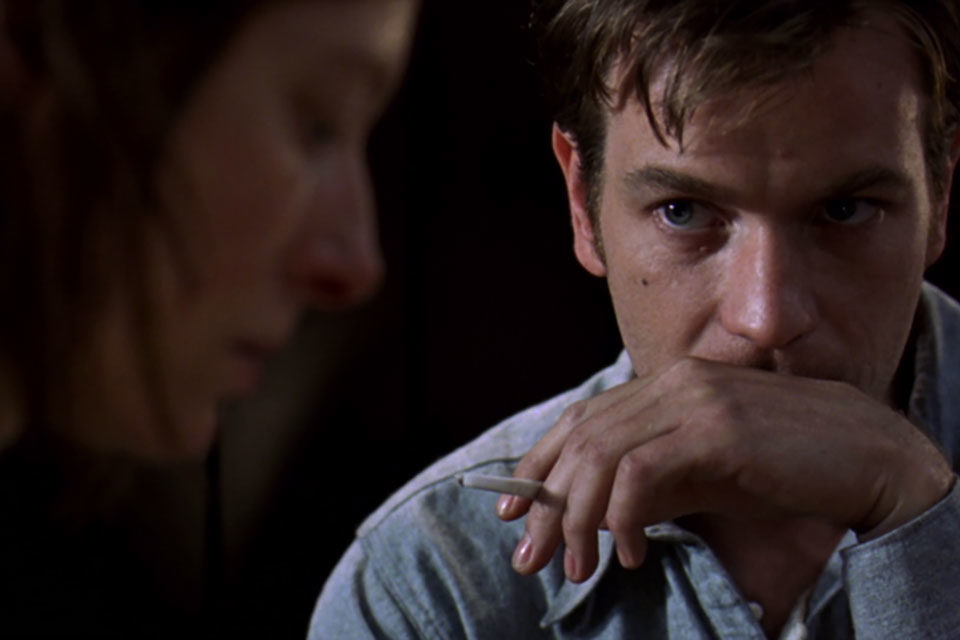

Pornography, from Polish director Jan Jakub Kolski, was a fine little film that seemed to get lost in the shuffle. This coolly intelligent Witold Gombrowicz adaptation refused to coddle or woo the audience, taxing the patience of daily reviewers. In truth, the film does take a while for all its elements to coalesce, but it builds to considerable power. The character of Fryderyk, the disenchanted manipulator of love games, played by Krzysztof Majchrzak, lingered in my mind for days afterward. So many of my favorite films in the festival, formal virtues notwithstanding, ultimately latched inside and took hold by reason of strong central characters: Hussein, the unforgettable pizza delivery hero/loser in Crimson Gold, with his delayed speech; Nicole Kidman’s Lady Bountiful in the steadily engrossing and meaty (to my surprise) Dogville; the solipsistic photographer Mahmut in Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s excellent Distant; Robert McNamara as himself in The Fog of War. By contrast, I found it difficult to engage with a film with a boring main character, however luminous the visuals. Ewan McGregor’s Joe, the sullen, bohemian drifter in David Mackenzie’s Young Adam, for instance, struck me as utterly vacuous (though the actor was obviously catnip to half the audience). I was also put off by close-ups of greasy egg dishes and other insistently grim in-your-face touches, not to mention the bleak industry of the sex scenes. Both heavy-handed and oblique, its hollow core made to seem complicated by scrambling the chronology, Young Adam was a tease, but I will allow that the waterfront canal scenes were prettily photographed.

Young Adam

For a much more subtle and deep study of masculine dogginess, one could not do better than Jacques Doillon’s Raja. Doillon, a French auteur of the first rank, too little-known in America, has been making psychologically complex features since the Seventies, and has never shrunk from probing the icky, power struggle aspects of male-female relationships (see The Woman Who Cries, for instance). At first Raja seems to be about imperialism: an older, wealthy Frenchman trying to seduce his 19-year-old Moroccan servant. But when his advances unloose the desires of this many-sided, vivacious teenager, he becomes confused and retreats, unable to believe she might actually care for him. Their mutual bolero of arousal, rarely in sync, offers a field day for cultural misunderstanding, for incorrect assumptions on both sides about the Other. Ultimately, the film strikes me as an honest analysis of male self-contempt, impotence, and fear of women—the protagonist’s supposed obsession with the girl masks his rejection of love, in a manner reminiscent of one of my favorite French films, Claude Sautet’s Un Coeur en hiver. The adroit, unobtrusively mobile mise-en-scène and the quietly expressive lighting (sun streaks on pink walls) make the film a sensual delight as well. It’s time for a full-scale Doillon retrospective.

Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn represented for me the perfect blend of narrative filmmaking and structuralist cinema. Using gorgeously composed master shots and keeping the camera patiently immobile, Tsai makes a near-empty theater the apotheosis of absence and presence, romantic disappointment and aesthetic ecstasy. Onscreen is a King Hu action movie, Dragon Inn, while off-screen, there’s enough rain, stasis, and decrepitude to satisfy Tarkovsky. The characters (a lame cleaning woman, a cruising Japanese homosexual, an elderly man whose eyes start to tear at a fight scene and you wonder what he’s actually thinking, a voluptuous slut cracking sunflower seeds with legs dangling over the seats) intersect spatially without yielding up their loneliness. Perhaps there’s some cinephile self-pity in this paean to the lost art of wasting one’s life in movie houses, but if so, the comic touches and the shimmering artistry of Liao Pen-jung’s photography redeem any hint of self-indulgence.

The Ozu retrospective, the fullest one ever mounted, was beyond praise, but its greatness made you realize what was often lacking in the main hall. Overall, this was not a particularly strong festival. I don’t blame the selection committee—they had to work with what was out there—but I do think the time has come to reconsider the festival’s structure and expand it beyond 26 events. In a year with a great crop (such as 2002), the exclusionary principle works well, and the festival becomes a kind of teaching seminar on the possibilities of cinema. In a weaker year, too many smallish, so-so films may be submitted to too harsh a critical scrutiny. Every year there are also heated discussions about edgy, problematic pictures that were omitted (such as last year’s Bowling for Columbine or demonlover); were the festival to be opened up to 50 or even just 35 features, it could be more boisterously provocative and representative in its inclusions, and less precious. The Film Society also needs to find a new venue for opening and closing nights than the acoustically challenged Avery Fisher Hall, especially for English-language pictures. Long may the New York Film Festival thrive; it is basically sound as is, but it need not be afraid to tinker with its structure.