A Stitch in Time

Harry Smith’s legacy suggests a peculiar paradox. He collected and preserved ephemera-paper airplanes, Ukrainian painted eggs, string art-yet destroyed many of his own films. Even those that remain seem fragile, near dissolution. Since cinema is used to record, document, and preserve experience, it’s ironic that Smith’s own film work seems as perishable as a string figure. Perhaps this reflected his view that it is uniquely human to want to make something by hand, however trivial. Smith’s Film Number 15: Untitled Seminole Patchwork Film was just one of the works that embodied this notion in the sixth edition of Views From the Avant-Garde, a two-day, eight-program event that consistently generated an ideal intimacy between artist and audience.

Static and spare, Smith’s ten-minute film is a catalogue of details of quilts shot in close-up. The montage of geometric patterns and colors reveals a discrepancy between the regular, repeated shapes and the irregularities produced by hand-stitching. Periodically, Smith cuts to the quilts’ undersides to reveal the jumble of thread behind their precise designs. Though the quilts’ patterns appear simple, the mottled clusters on their reverse sides suggest an unfamiliar language-one which, to the initiated, represents years of tradition and rigorous craftsmanship. Smith gives us a precious opportunity to view these quilts in a new light, and in doing this, he foregrounds the extent to which their language is as complex and highly personal as the one he speaks through film.

Also inspired by film’s capacity to record and preserve, German filmmaker Heinz Emigholz traveled around Switzerland and the Midwest to complete Maillart’s Bridges and Sullivan’s Banks. Both are biographical portraits of 20th-century architects (Robert Maillart and Louis Sullivan) as represented by the bridges and banks they designed, which are presented as they exist today, in order of their creation. Emigholz’s stationary shots capture the manner in which these artists expressed themselves personally within the parameters of engineering. Grouping structures that would otherwise require weeks of travel to view, he condenses the partial biographies of his respective subjects into these compact films, which run to 24 and 38 minutes. In so doing, he’s created the cinematic equivalent of an idea Sullivan expressed in his lectures, when he spoke of our potential capacity to intuit life through the man-made forms around us.

Regarding Penelope’s Wake

In keeping with Harry Smith’s affection for ephemera, Emigholz’s The Basis of Make-Up (II) adopts a different approach to biography. Again working from sync-sound footage shot with a fixed camera in multiple locations, the filmmaker meticulously records the contents of 69 notebooks compiled over 16 years—one part of the director’s own creative output. We’re shown every page in every book, in shots that last a few seconds at the most. The handwritten texts are impossible to read, but we glimpse hundreds of images clipped from magazines and newspapers, representing years of pop cultural detritus pasted onto virtually every page. Like the monuments in his architecture films, this collection of writing and collage effectively turns The Basis of Make-Up (II) into a profile of a man in dialogue with his own culture. Emigholz has taken Sullivan’s message to heart, ensuring that his own ideas will endure because they’ve been given material form, catalogued on paper and definitively recorded on film.

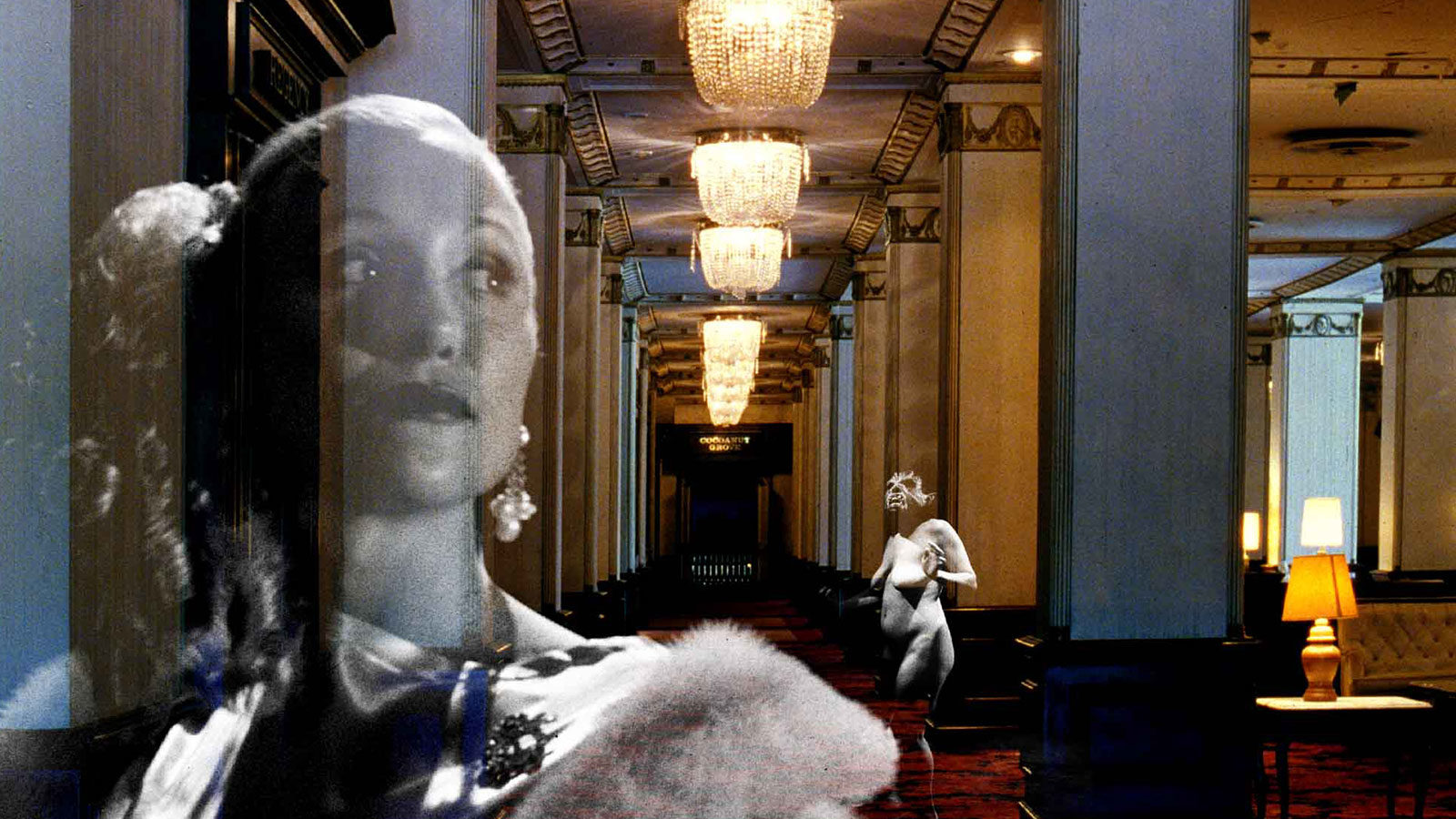

In Pat O’Neill’s bravura The Decay of Fiction, fragmentary, interwoven narratives are situated in Los Angeles’ deserted Ambassador Hotel. A former locus of Hollywood’s Golden Age and the site of Robert Kennedy’s assassination (and in the past 30 years, many low-budget movie shoots), the hotel now awaits demolition. O’Neill documents the building’s empty, rotting interiors with time-lapse photography and motion-control camera techniques, and entire days seem to pass in seconds. Over this footage, he layers black-and-white sequences of actors in period costume and combines sound clips from Forties and Fifties noirs with his own scripted dialogue. The translucent figures who move through the hotel’s spaces seem to bleed from the very walls, and the film assumes an increasingly horrific tone as its multiple scenarios expand to encompass sexual intrigue, betrayal, and murder, with demonic figures emerging at intervals, as if to celebrate the corruption on display. O’Neill’s effort to imagine and resurrect a world that might be sustained within the Ambassador’s once glamorous suites and hallways is a direct response to L.A. culture’s tendency to demolish buildings once they fall out of step with popular taste. And by layering documentary and fiction, the film also addresses the discrepancy between Hollywood’s version of reality and life as it’s actually lived. What remains unresolved is how O’Neill feels about the Ambassador: is it merely an empty shell, just another movie set, or does it embody the underside of human nature as he envisions it?

Echoing The Decay of Fiction, Michelle Smith’s elastic and monumental Regarding Penelope’s Wake is a litany of layered, incised, and reiterated found images whose juxtapositions convey humanity’s animalism. The circumstances of her film’s creation ennoble its depiction of our primal drives. Smith abandoned filmmaking for eight years to sell antiques, a trade that appears to have served her well—she has a collector’s eye. She took over 18 months to edit her material, which was mined from flea markets and acquired over the Internet. Silent and unfolding over two hours, Regarding Penelope’s Wake exists only as an unprojectable workprint—it was screened on video. Due to its length and the intensive manipulation and layering of its footage, the film is as much a sculptural object as a performance or experience. Its physical existence elucidates the action it portrays—the dedication behind its completion suggests that personal expression is as fundamental a need as eating, shitting, and fucking. Smith specifically aligns her approach with weaving a textile, which brings us back to Harry Smith’s quilts. Many of her techniques are found-footage filmmaking clichés (countdown leader, hand painting), but she adapts this pre-existing language to convey something about her life during the period in which she was making the film. At the same time, the material’s associations are subtle enough to leave room for viewers to make their own connections. It’s this characteristic that makes Regarding Penelope’s Wake a gift to its audience. Michelle Smith spent years recovering forgotten junk so that she could hold up a mirror and allow us to see ourselves.