Private Investigations

Nathaniel Dorsky says his recent works are the products of long walks. With his camera always at arm’s reach, he gathers his material on foot, later editing it into films. Walking fires the intellect and assists meditation, which in turn not only facilitates Dorsky’s process but becomes a part of the film itself. The viewer can intuit through every frame of his most recent work, Love’s Refrain, that it is the result of such adventures—a series of incandescent shots bound by chance. Dorsky’s film serves as a coda to three previous works, Triste (96), Variations (98), and Arbor Vitae (00), and derives its subtle narrative from a montage of everyday images, long in duration and remarkable for their texture, vivid color, gentle movement, interplay of light and shadow, and capacity to convey profound emotion. The shots are loosely linked and never repeated, but certain motifs recur, encouraging us to make our own associations—the color red, light streaming through trees, images of equilibrium—the wind gently moving a boat moored by rope, or flowers held in place by string, their tethers relaxing and then becoming taut again, each object constrained yet free to move. Dorsky’s work is always silent, prompting the viewer to devote full attention to the image. Again, if walking promotes introspection and such concentrated thinking subdues the noise of our surroundings, then the film’s silence, in combination with its leisurely pace and use of images drawn from daily life, makes the experience of watching it much like being led by a generous guide through familiar surroundings; the beauty that arises from such intensified observation is a great gift to the viewer. Dorsky’s work, born out of endless curiosity, is committed to the power of the visual image and the singular bond between filmmaker and audience. For this reason Love’s Refrain was a perfect place to begin the NYFF’s fifth annual Views from the Avant-Garde programs, concerned as many of the films were with cinema in its most spare and fundamental forms.

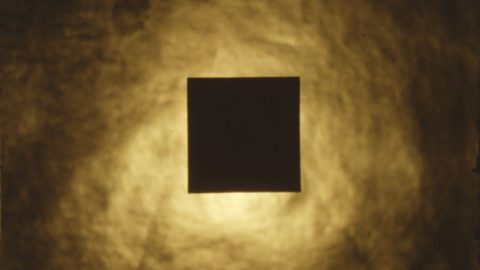

For example, Minyong Jang’s The Dark Room is on one level an exploration of cinema’s pre-history. It was shot entirely inside “The Giant Camera,” a camera obscura (literally: “dark room”) located above San Francisco’s Ocean Beach. The device is essentially a giant pinhole camera with a lens located in a revolving turret, a characteristic unique to this particular camera obscura. Light enters the room through the lens, and is reflected by a mirror onto a concave basin that acts as a screen. Its imagery is limited by its location, but what does change is the quality of light, something that’s dependent upon the time of day and year. Since he’s shooting the image projected onto the basin, the result is dark and faint, the film beginning with a fragile view of the ocean framed in the shape of an oval. As it progresses, the frame’s dimensions expand, the camera moves closer to the ocean’s surface, and the water’s movement becomes more dramatic—in various shots it descends steeply, roils violently, and appears to defy gravity altogether. At one point Jang uses the turret’s movement to execute a grand gesture, a pan from the highway that runs alongside the shore, across the beach, and out across the sea. The most amazing thing about The Dark Room is its broad scope, which it achieves in spite of physical restrictions. Though its images are taken directly from nature, they’re manipulated by the camera in ways that seem to run counter to all natural laws, offering the kind of disorienting views and limitless perspectives only cinema can provide.

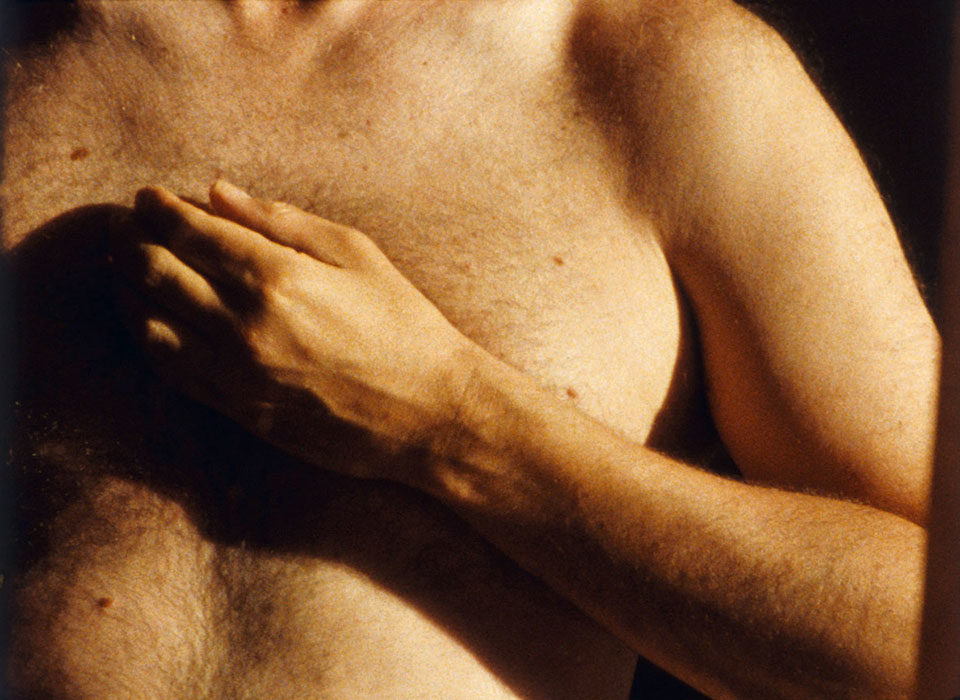

Like Love’s Refrain, Robert Beavers’s The Ground employs a subtle narrative, establishing a parallel between stonecutting and film making. Beavers poetically suggests that constructing images is much like laying bricks, a painstaking process of joining pieces that eventually form a whole made more profound than the sum of its parts. The Ground’s camera movements are more emphatic than those in Love’s Refrain, and although its palette of repeated sounds and images is limited, they’re presented in new combinations throughout, prompting new interpretations of each visual and aural device. Intended to serve as the last film in three cycles composed of 18 films altogether, The Ground was shot in Greece at the same location as one of Beavers’s very first films. It opens with a shot of a tower in ruins. With its earth tones that set the film’s color scheme, and its crags and spiked bushes, the landscape is at once warm and forbidding. Beavers cuts from the tower to his own bare torso as he holds his cupped hand against his chest and rotates it outward as though releasing something. Following this, we see a shot of a mason hammering a chisel into a rock. The filmmaker eventually makes a fist, its shape resembling that of the circular tower, and hits his own chest. The Ground’s photography is exquisite, but it’s the film’s percussive rhythm that really cuts to the quick. The thud of Beavers’s fist, the flapping of birds’ wings, and the crack of chisel on rock convey the tangible physical presence of the body and its surroundings.

The Ground

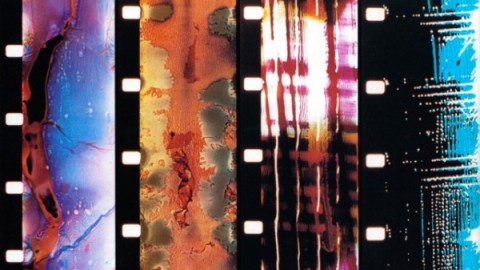

An assortment of ticking clocks throughout Peter Tscherkassky’s Dream Work (for Man Ray) lend it a similarly percussive quality. Since the film is an homage to Man Ray, its steady beat calls to mind Ray’s metronome, “Object Indestructible”; in fact, Dream Work takes off from Ray’s Rayographs, images created by shining light on or through physical objects placed directly onto unexposed film stock. Tscherkassky’s film is the third in his CinemaScope trilogy, all of which employ contact printing to transfer found footage. Lifting shots from the disturbing 1982 horror film The Entity, (also the source of his 1999 found footage film Outer Space), Tscherkassky tells the story of a woman who falls asleep and begins to dream. Gradually, recognizable shapes and faces are replaced by abstract images flickering on the screen, seemingly spiraling through space. These strobing forms, in concert with the stuttering soundtrack, convey an alarming vision of menace and doom.

Sharing The Ground‘s emphasis on concrete physical presence, Scott Stark’s Angel Beach was easily the most accomplished and satisfying film in the five programs. Stark animates 70 stereoscopic slides of young women in bathing suits taken by an anonymous photographer on Northern California beaches some 30 years ago. The slides consist of two photos shot simultaneously from fractionally different perspectives to give the effect of three-dimensionality, and so by cutting rapidly back and forth between them, Stark makes the figures appear to shake and vibrate. The result: an orgiastic beach movie filled with fleshy young bodies shuddering in apparent arousal. Women are caught in the act of bending down or standing up, their breasts heaving and hips gyrating, the illusion of movement accentuating the overt sexuality originally present in the photos, one that’s either expressed by the subjects themselves or via the photographer’s attitude towards them. The beachgoers are evidently unaware that they are being photographed, so there’s a perverse aspect to Stark’s film—as you wonder how and why the photographer was able to get so close, the pleasure that comes with looking at these lithe young women in various states of seeming ecstasy is mixed with a sense of unease. Angel Beach occupies a fascinating position, somewhere between documentary (inviting us to scour the images for clues as to their origins) and extremely voyeuristic spectacle.

The same mix of voyeurism and detective work is apparent in Lewis Klahr’s The Aperture of Ghostings. Like Stark, Klahr found his material in a thrift store—contact sheets of photographs in which three different women assume the seductive poses of aspiring actresses or models. Klahr attempts a mixture of actual and fictive biography through animated collage. Exploring the possible histories of each women in turn, the triptych of films evokes an early Sixties iconography of cocktail culture and utopian aspiration coexisting with the vibrant calendar grids and color samples that lend Klahr’s work its own pop art sensibility.

The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found)

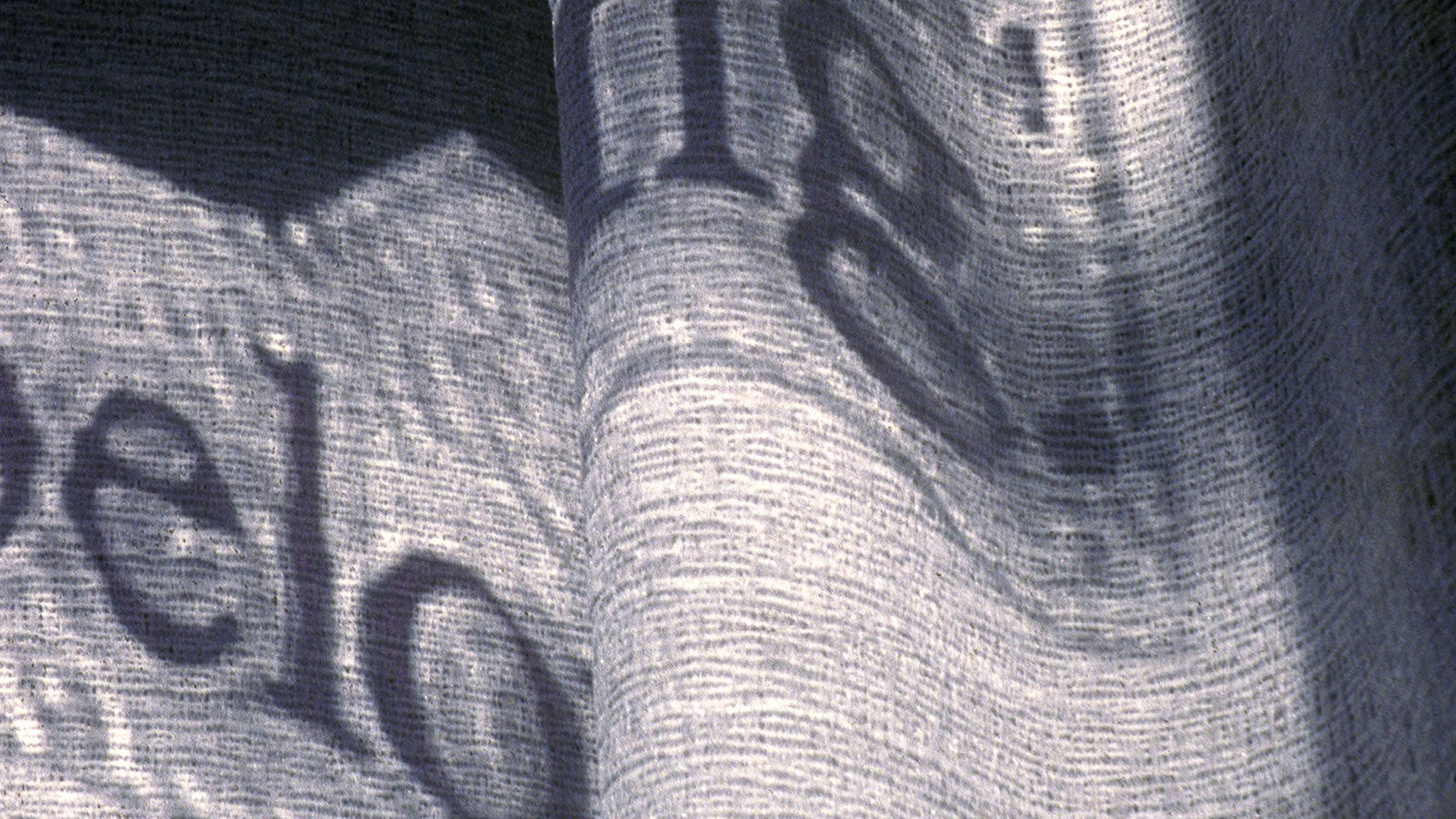

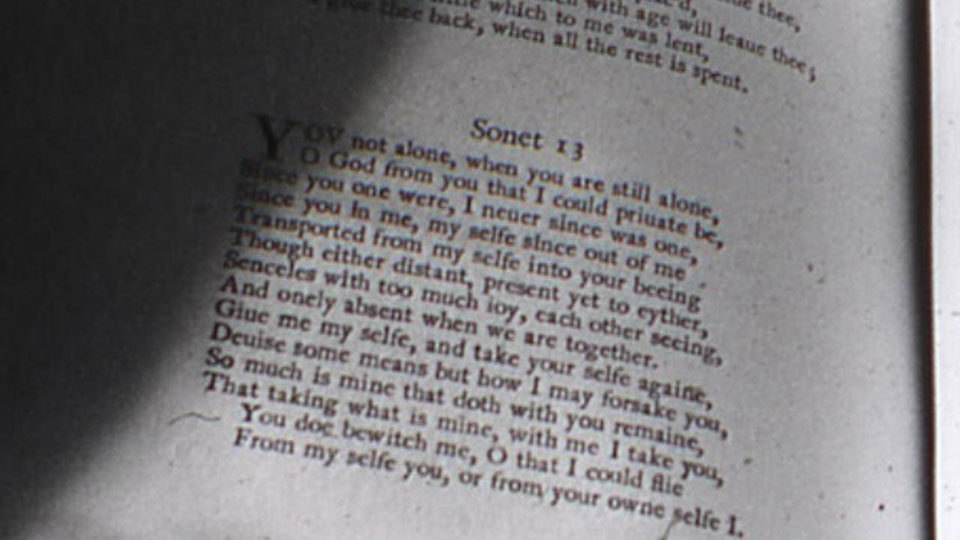

David Gatten’s film The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found) is also a biographical investigation, but rather than interpreting the lives of 18th-century Virginian William Byrd and his daughter Evelyn through their images, Gatten approaches his subjects primarily through text. Divided into three parts, the film begins with a series of what appear to be microfiche catalogue entries for books from the Byrd family’s vast collection. The words become increasingly difficult to read until we’re forced to accept them as purely graphic elements. The second section maintains the same microscopic scrutiny, studying what appears to be a candle in such extreme close-up that the accumulation of wax forms cell-like clusters analogous to the books that together constitute the Byrd library. The third section shows the spines and edges of books favored by Evelyn, including a shot of one open to a page featuring a poem by Drayton. Gatten’s approach to biography is unique: the books that he cites have been selected for what they reveal about his subjects. The film’s devotion to reading as a solitary and deeply personal pursuit is a romantic one, and its implication that the art we surround ourselves with will live on as evidence of our existence is both consoling and inspiring.