A Boquet of Grief and Sex

Grief, sex, work (or the lack thereof), and dreams were the staples of the 39th New York Film Festival. Perhaps that’s true of all film festivals, but this year the relevance of grief was particularly evident from the subdued mood of moviegoers, still raw from September 11, asking each other: “Are you all right? Did you lose anyone?”

Needing escape, I managed to see all the features this year, and can’t help reassembling them in my mind, like bouquets, by preference and theme. My favorites (to kill the suspense immediately) were the Oliveira, Lynch, Breillat, Rohmer, Tsai Ming-liang, and Lanzmann; my biggest disappointments, the Imamura, Moretti, Chereau, and Godard. That left the majority of films in the modestly likable or conflicted-response category, for reasons that follow.

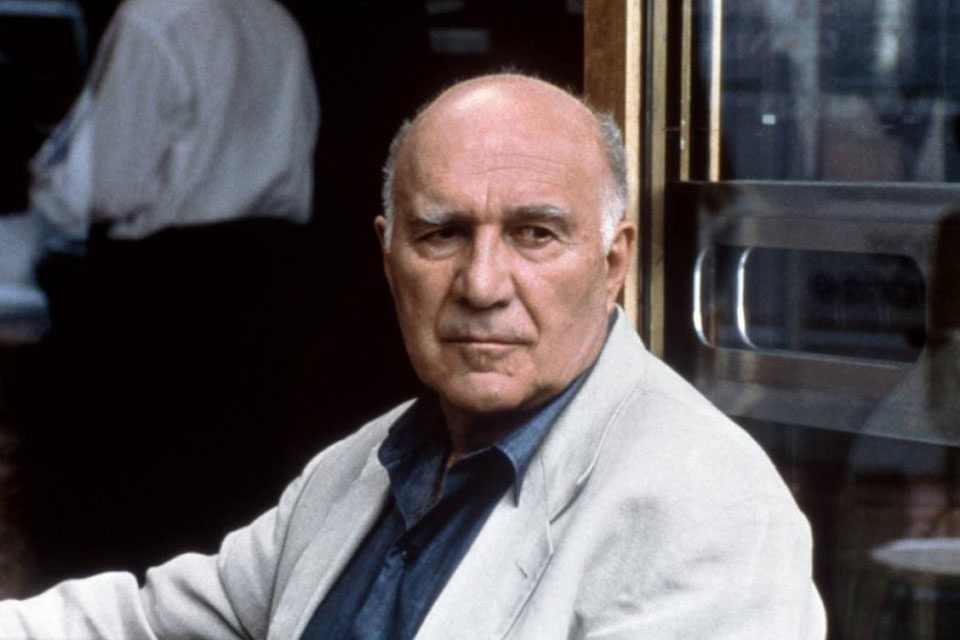

I will start with what to me was the best film in the festival (still without a distributor): Manoel de Oliveira’s I’m Going Home. A surprising work from the Portuguese master of stylization, much more realistic, rather like late Claude Sautet, this extremely well written and impeccably shot study of an elderly actor (Michel Piccoli) who must cope with the accidental deaths of his wife, daughter, and son-in-law has an equilibrium steeped in elderly wisdom. Piccoli turns in a magnificently rounded performance, braiding stoicism and irritability, solipsistic pride and openness to the world. For a film with so dark a subject, it’s surprisingly light and comic in places, as the actor seeks pleasure in his work and his grandson, whom he is now raising. But the final shot, showing the child’s face registering that he may soon suffer another loss, as his grandfather falteringly climbs the staircase, is one of the most piercing on film.

I’m Going Home

Perhaps Oliveira’s restraint in not beating us over the head with Grief Management made the film all the more powerful for me, whereas Nanni Moretti’s The Son’s Room, about a family jolted by the death of their teenage boy, had the concocted, programmed air of an Elisabeth Kübler-Ross diagram. In the past I’ve been a huge fan of Moretti, but this time he has expunged the comic, and with it goes his intelligence. Particularly “off” is Moretti himself as the protagonist: forgoing the usual dose of contrarian eccentricity, his character is left too undefined, a conventionally simpatico shrink who listens badly. The embarrassing therapy scenes all show the patients self-indulgent and their doctor bored. Moretti’s protagonist is never given the chance to process through his professionalism, like Piccoli’s, the unassimilable facts of grief.

Jacques Rivette’s Va savoir has much to tell us about the consolations of work amidst desire’s confusions. It’s an elegant, gracefully adult film, especially in the scenes between the actress (Jeanne Balibar) and her director-lover (Sergio Castellitto). I was entranced for the first two-thirds, then ungratefully irritated that it didn’t deepen, like a Lubitsch, but stayed obstinately playful, with its farcical last act of lost rings and trampolines, and its unnecessary brother-sister subplot. On the other hand, I stayed contented all the way with Tsai Ming-liang’s What Time Is It There?, in which whimsy and grief go hand-in-hand—perhaps because its Taiwanese melancholy had the final word. You have only to watch the fishbowl scene, the hero feeding a cockroach to his pet fish, or his mother summoning her dead husband by any means necessary, including masturbating with an urn containing his ashes, to appreciate the mix.

Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners is a charming, becomingly modest ensemble piece—the first Danish Dogme film I could bring myself to like. What worked for me were the uncartooned, well-observed characters, maimed and grief-stricken in different ways (three have recently lost family members!), all shyly seeking each other out, through the pretext of studying Italian. Especially appealing is Anders W. Berthelsen’s intelligent performance as the new minister, trying to stay human behind his robes. The movie is tender and sweet, terms that need not be taken pejoratively.

Silence. . . We’re Rolling

Another light, oddball treat was the veteran Egyptian director Youssef Chahine’s Silence. . . We’re Rolling. This deliriously goofy pastiche about a diva (played by the Tunisian singer Latifa) who falls in love with a younger, celebrity-mad gigolo pretending to be a psychoanalyst mixes elements of Imitation of Life, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Band Wagon with the stock comic bits and minor characters that show up on Egyptian cable—the Middle Eastern version of Bollywood. Do not expect a sociological glimpse of modern Cairo: you will, however, see Latifa don a series of stunning gold, turquoise, and carmine gowns and sing fabulously. She is irresistible as a woman who cannot stop playing to the hilt whatever part life has thrown her: the rejected wife, the infatuated divorcee, the self-abnegating mother.

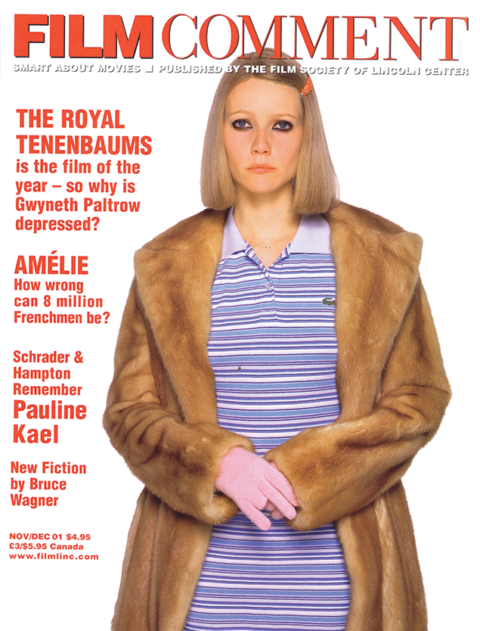

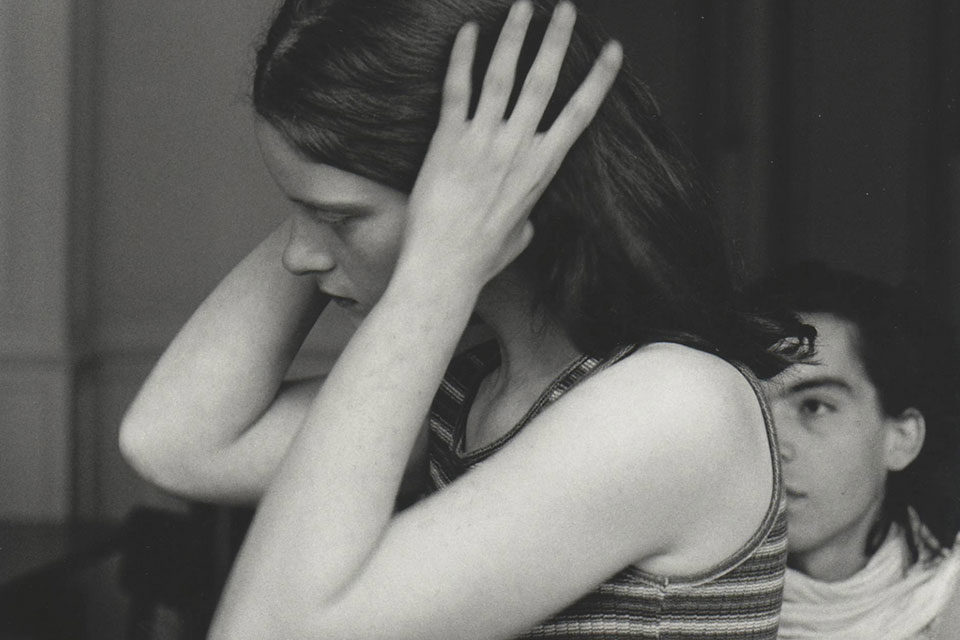

Where would film festivals be without the coming-of-age story? This year, we had Fat Girl, Baran, Storytelling, Y tu mama también, La Ciénaga, Deep Breath, and All About Lily Chou-Chou to remind us of the traumas of adolescence. Strongest by far is Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl, a consummate if astringent depiction of the power games played by, and on, teenage girls. Breillat shows a mastery of composition within the frame, especially in the long, triangulating bedroom scenes. Although the violent ending gave me problems—I was too won over by the patient, novelistic method that had preceded it to warm to this disruption—I remain in awe of the film’s psychological understanding and cinematic tact.

Fat Girl is being promoted as a “provocation,” but only the ending provokes; the rest is wry, realistic, and very sad. Todd Solondz, on the other hand, comes on in Storytelling as a provocateur, start to finish. You can feel him trying to irk you, with his sympathy for the devil and crude social satire. The aggressive sensationalism in Happiness turned me off, so I was surprised to be utterly taken by the first episode in his new two-part film. It’s not only that the self-absorbed student with cerebral palsy and the sexually rapacious yet weirdly truth-telling black creative writing professor are so outrageous, but that the outrageousness has a focus, a point. The scene in the bar, with the professor (Robert Wisdom) intimidating the coed (Selma Blair) into throwing herself at him, is perfectly paced, as Frederick Elmes’s exquisite color-noir photography catches the red glints in his eyes. Unfortunately, the longer second episode is more diffuse, sarcastic, and unoriginal: call it Happiness, Part 2.

Baran

The petulant Afghani teenager scratching out a living as a construction site errand boy in Majid Majidi’s Baran seems at first an unlikely candidate for our sympathy. We are deeply ensconced here in Iranian neo-realism: the film’s first half rewards our curiosity by offering unhurried glimpses of the work process and the construction site’s pecking order, with its legal and illegal workers, and its harried middle-man overseer. Gradually, the teenage boy realizes that the new worker whom he had detested as a weakling is a girl in disguise, named Baran, and he falls in love with her from a distance. Much of the film’s remainder is taken up with his watching her from behind trees and walls, not daring to approach. There is a wonderful moment towards the end when the girl, reveling in her newly found seductive power, lowers her veil, taking herself away forever, and simultaneously giving him hope, or at least a glimmer of what might lie in store. When he sees her doorway, it suddenly becomes, don’t ask me how, a mystical Sufi symbol of heaven’s portal. Majidi has been guilty in the past of syrupy, uplifting sentimentality; this time, the camerawork is more severe, the storytelling more measured. It’s his best film by far, but I still wonder if it’s not too simple, too allegorical.

The strongest documentary this year, Claude Lanzmann’s Sobibor, October 14, 1943, 4 P.M., also surpassed most of the feature films in sheer story power. The title refers to the one uprising by Jews in a Nazi-run concentration camp. The first part of the film alternates an interview with Yehuda Lerner, the lone survivor of that rebellion, with Lanzmann’s footage of appropriate landscapes and sites. Lanzmann has never been given the credit he deserves as a film craftsman. His images of Poland have a stark, graphic color palette, held just long enough. In the second half, Lerner’s testimony becomes so gripping that there is no point in cutting away from his face, the corner of his mouth twitching, the eyes ablaze with memory. The picture turns into a grisly, Hitchcockian murder story—Torn Curtain, say: first the Nazis kill the Jews, then the Jews kill the Nazis. Lanzmann’s sadistic side surfaces, as always, with his bludgeoning, raspy recitation of the transport figures for Sobibor; but, like everything else in the film, it works.

Another mature chamber drama, as it were, haunted by history and bloodshed, was Eric Rohmer’s The Lady and the Duke. I loved this movie, much more warm-blooded than Rohmer’s earlier period films. Set in the French Revolution, it makes scant attempt to re-create the spectacle onscreen, using paintings as backdrops, yet it shows the deepest imaginative engagement with the times, ideas, and historical characters. At its center is Grace Elliott (Lucy Russell) a plucky Scotswoman who has emigrated to France and become more Royalist than the king. The French treat her with polite condescension, like a foreigner who just doesn’t “get” it, perhaps because the rights she insists the aristocracy receive have a rather English ring to them. The duke, her ex-lover, now in the Jacobin camp, insists he won’t talk politics with her, yet keeps returning, possibly to hear from her lips the old monarchical rhetoric he grew up with. The scenes between these two are reminiscent of My Night at Maud’s: liberal and conservative trying to wear each other down. This time it’s the woman who’s conservative, and their erotic passion’s already spent, but there is still the intellectual respect, and the sparks it strikes. (It’s the reverse of Patrice Chereau’s execrable Intimacy, whose two protagonists rut at each other, but don’t become fully realized characters capable of articulate dialogue until the movie is almost over.)

In Praise of Love

Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love, Richard Linklater’s Waking Life, Shunji Iwai’s All About Lily Chou-Chou and Laurent Cantet’s Time Out all address, in different ways, the numbness and melancholy of future shock, brought on by present-day problems such as technology, globalization, unemployment, and virtual reality. Godard’s latest is a continuation of the essayistic, ramblingly epigrammatic style he used in Germany Year Ninety, Hélas pour moi, and For Ever Mozart. Not since Nouvelle vague, however, has he shot anything with visuals this breathtakingly composed; and you have to go back to his New Wave classics to rival the footage of Paris. The images are as ravishing as the anti-American polemic is tedious. Godard, not happy about the way the modern world has turned out, has a ready villain to blame for everything slimy. He also asserts, fatuously, that Americans have no grasp of the past, and so they must go around buying up the memories of Europeans who resisted tyranny. I have no more patience for this petulant scapegoating. I hope when Godard is 90 he will have acquired the wisdom to make a film as deeply fair as Oliveira’s.

What might be called the Baudrillard problem—the eradication of real life by the media’s programmed dreams—is given full expression in Richard Linklater’s Waking Life. The innovative animation, which translates digitally-shot live footage into the equivalent of a flow of paintings by Alex Katz or David Hockney, keeps the viewer consistently off-balance, while the constant talk, everything from intelligent speculation to dormitory bullshit to paranoid raps, makes it necessary to pay close attention. Though one character comments on “how exciting alienation can be,” the young wanderer who links it all seems less excited than scared. For all the allusions to parallel universes and dream-states, the film has a documentary sound (like one of Fred Wiseman’s place-studies, such as Bangor, Maine) which plunges us without introduction into the middle of obsessive conversations. Does it build? I’m not sure yet. What I take from it is: a) the giddy excitement of formal experiment; and b) an underlying malaise of surprising intensity, less reconciled than the mood in Linklater’s earlier “epic,” Slacker. A radically alienated discontent—offered as a special sensitivity of youth—also under-girds Iwai’s All About Lily Chou-Chou. I might be tempted to see this misery as specifically contemporary, the result of a deracinated, globalized Japan, were it not for the fact that Japanese youth has long been drawn to morose pessimism, from Osamu Dazai, the cult writer who committed suicide in 1948, onwards. The film follows, more or less, a group of teenagers saturated with suicidal loneliness, as they ache for a transcendence only to be found in rock music. Iwai, who has made many music videos, can do anything he wants with mood, lighting, color, and composition; he is one bravura filmmaker, and he rains down this polished, empathic imagery on our heads for two and a half hours. The story does not so much unfold through its characters as accumulate in atmospheric globs and violent bursts. Maybe this is where films are headed: a cascade of pre- or post-cortical affect. Laurent Cantet’s Time Out, a preemptive strike on the Coming Unemployment, is positively Apollonian, or Chabrolian, as it calmly tracks its protagonist, a fired office worker pretending to his family that he is still on the job. A hit with audiences, I found it to be a one-note tour de force, not nearly as gripping as his terrific debut film, Human Resources. Still, the scenes of the hero hanging out in a corporate tower, pretending to take a meeting, are not easy to shake. Another film that generated considerable buzz, Lucrecia Martel’s La Ciénaga, won me over with its accomplished, long-shot camera style and behavioral attentiveness. Following in the footsteps of Buñuel, Torre-Nilsson, and Almódovar, this newcomer nevertheless accords her dysfunctional, fucked-up families a cool regard purged of camp. By bringing us news from an outlying precinct of the world, in a solidly sophisticated film style, La Ciénaga typified the pleasures to be gotten from this year’s NYFF—all in all, a pretty good lineup.