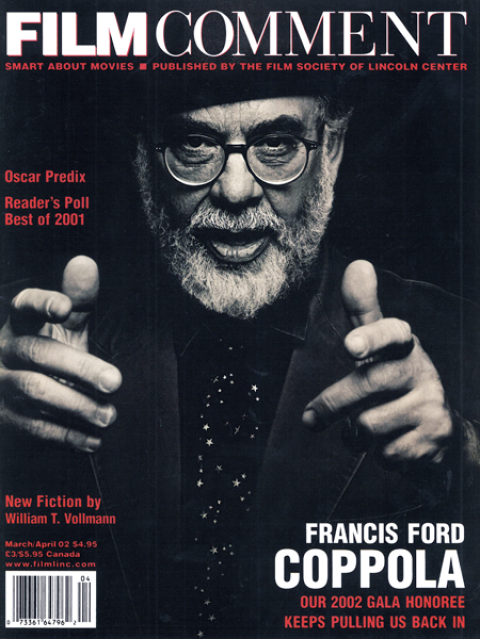

Myth Maker: Francis Ford Coppola

To celebrate the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Film Comment will be making some classic pieces from our archive available online. This week, read Kent Jones’s appreciation of Francis Ford Coppola, FSLC’s 2002 Chaplin Award Gala honoree.

There are few spectacles in American cinema more touching than the career of Francis Ford Coppola, one-time Roger Corman protegé and script-doctoring wunderkind, now creative grand old man of Hollywood.

The mammoth undertaking of the Godfather trilogy; the exhaustively documented ordeal of Apocalypse Now; the impossible dream of American Zoetrope, that eternally returning, mythological entity, first as a mere production company, then as a cinematic artists’ utopia and multimedia empire, that once brought Michael Powell, Jean-Luc Godard, and Monte Hellman under its wing; the endless tinkering with The Escape Artist and Hammett, and the various presentations of Syberberg, Kurosawa, and Koyaanisqatsi, among others; the real-life misadventure of The Cotton Club; the long stretch of insolvency, nipped in the bud by Bram Stoker’s Dracula: what do all these various enterprises and legends add up to? Coppola has cultivated the image of a brilliant, nervous impresario who alights on projects according to the dictates of his fancy—a wine label here, a phantom casting call for On the Road or a new publishing venture there. Clearly, a man with a phantom project called Megalopolis on the back burner has a whole universe in his head, far more expansive and more magical than anything possible in drab old reality. And what’s so touching is the way he attempts to share the oceanic vastness of his imagination with his audience. Thus the very public tug of war between projects both manageable and unmanageable, real and unreal, between supreme confidence and punishing self-doubt, and between the grand gesture and the intimate exchange. The man who once dreamed of turning Goethe’s slim Elective Affinities into an epic holographic movie to be projected on special glass screens that overlooked the Rockies is the same man who cooked up a big batch of sausage and bean soup and ladled it out to the customers waiting on line to see One from the Heart at Radio City Music Hall. There’s something uniquely moving about Coppola’s need to bring us all under his tent and waltz together to the music of the spheres. It accounts for the lovable goofiness of some of his smaller films, where he’s looking for a shortcut to grandeur. Like The Outsiders, his little teenage film “without any English on it,” in which the bodies appear mountainous and the images seem like they’ve been coated with the nectar of the gods. Or the lunatic gorgeousness of the reviled but hypnotic One from the Heart, in which a quartet of affable performers playing “ordinary people” is sent gliding through action that feels like it could be taking place on the moon.

More than any other director since the silent era, Coppola thinks like a conductor. There have been plenty of musically inclined filmmakers, but precious few for whom all the elements of a film function like the different sections of an orchestra, or for whom the musical experience serves as such an apt metaphor for the effect of the final product. On a scene-by-scene level, it’s reflected in his absolutely perfect sense of rhythm: Coppola is such a graceful filmmaker that he makes a Lean or a Hitchcock seem fussy by comparison. The helicopter attack in Apocalypse Now is unparalleled for its command of space (physical and sonic), motion, and momentum, culminating in that deeply, disturbingly satisfying swoop down over the frightened, running peasants. No less spectacular is Mickey Rourke’s Motorcycle Boy in Rumble Fish, revving his engine, launching his bike at his brother’s stunned assailant, and sending the kid sky high. Or the slow, careful buildup to the blood bubbling up from the toilet in The Conversation. On a less ornate but no less ominous level, there’s the exquisitely timed entrance of the deadly Don Lucchesi in The Godfather Part III. The camera is on Andy Garcia and Eli Wallach, they hear the sound of weapons clicking, they turn and Coppola cuts to reveal this smiling, modest European gentleman appearing as if by magic amidst a throng of bodyguards.

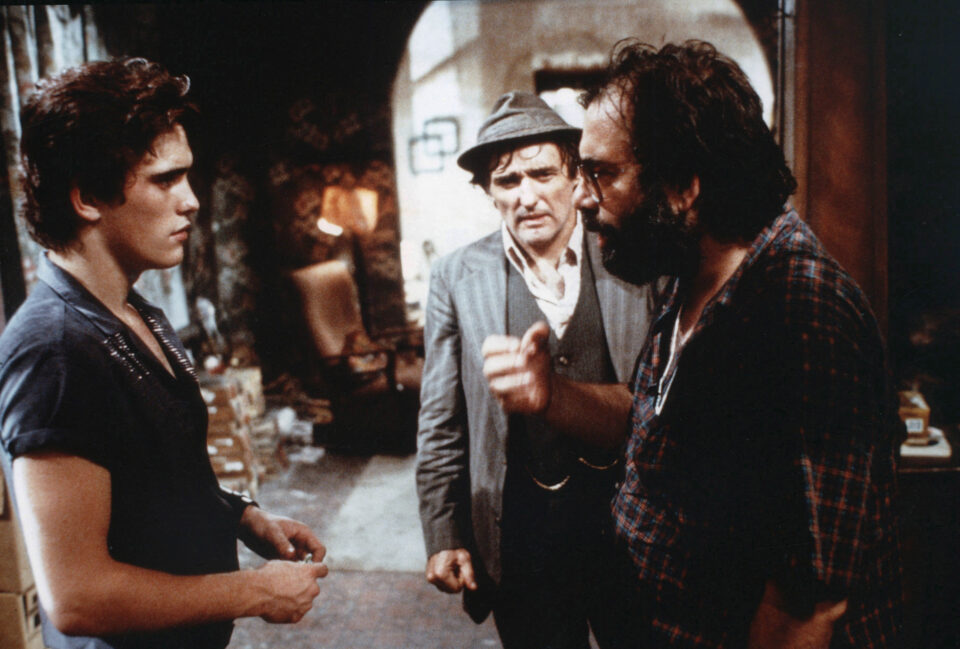

Matt Dillon, Dennis Hopper, and Francis Ford Coppola on the set of Rumble Fish, 1983

The arc of Coppola’s great films is uncomplicated, in the way that the arc of a Verdi opera is uncomplicated, quite different from the spiky, modern trajectories of a Kubrick, a Scorsese, or a Malick. With Coppola, the sweep of emotion contains history, politics, philosophical uncertainty, everything. I want to emphasize the word “contains,” so that it won’t be confused with “eclipses,” because that’s what makes him a great director as opposed to a calculating entertainer. Coppola uses history—recent history—as his template, and tunnels deeper and deeper until he arrives at a molten core of emotion, always revolving around issues of power and security: the all-consuming, paranoid amassing of power at the end of The Godfather, multiplied by ten at the end of Part II; the obsessive cultivation, or hoarding, of security, consuming itself at the end of The Conversation; the brutal logic of murder as the end point of Apocalypse Now; and finally, the ultimate fragility of power at the end of The Godfather Part III. Even in a film of lesser scope like Rumble Fish, where a teenage novel is retooled into a mythological narrative, the security dilemma is still there: how do you step out of the shadow cast by a charismatic older brother and become yourself? Loneliness is the thread that runs through all of Coppola’s work, from Shirley Knight’s runaway wife to Michael Corleone to Harry Caul to Captain Willard to Peggy Sue and beyond. But it’s a very particular brand of loneliness. It has to do with the sense of feeling like you’re in the world but not quite of it, cut off whether by accident, temperament or destiny. Even Jeff Bridges’s Tucker, the annoyingly ebullient maverick (minored by the monotonously bright, disappointingly one-note film around him), is a man alone with his dream. This aloneness is what gives the films their poignancy.

Characters are always nesting in Coppola, getting comfy in their lairs, hideouts, and home bases: the Corleone family in their Long Island and Tahoe compounds, Harry Caul in his apartment and his studio, Colonel Kurtz in his stronghold, the silent father retreating to the abandoned car in the undervalued The Rainmaker. Or, like Shirley Knight’s runaway wife in The Rain People, they’re looking for shelter. And this nesting effect is often echoed in the imagery. Coppola swathes his characters in light and shadow, leaving them comfortably ensconced within the frame, whether the subject matter is an upriver trek through Vietnam, a time-tripping journey back to adolescence, the career of a boundlessly confident car manufacturer, or a power struggle for control of the European conglomerate Immobiliare. Coppola composes images in which people and things exist in cozy harmony, and every wedding, nightclub, business meeting is a vision. Each moment in the young Vito’s tiny Lower East Side apartment in The Godfather Part II has the richness and warmth of Christmas dinner. Mickey Rourke’s Motorcycle Boy, the Camus of Tulsa, leans against a wall under a big clock in Rumble Fish, joined by Matt Dillon’s Rusty James. The deep black and white image, almost halated, feels like the Bergman of Persona, and the existential clock is right out of Wild Strawberries. But the feeling is a world away, as congenial as anything in Hawks or Walsh. The endings of The Godfather Part II and III are so uniquely powerful because the image is emptied out and Pacino is left alone in the frame, as exposed as the underfloor of Caul’s apartment at the end of The Conversation. A scene that encapsulates Coppola’s obsession with security and warmth: Kathleen Turner’s first rush of feeling when she realizes she’s a teenager again, back home with her mom and dad, in Peggy Sue Got Married.

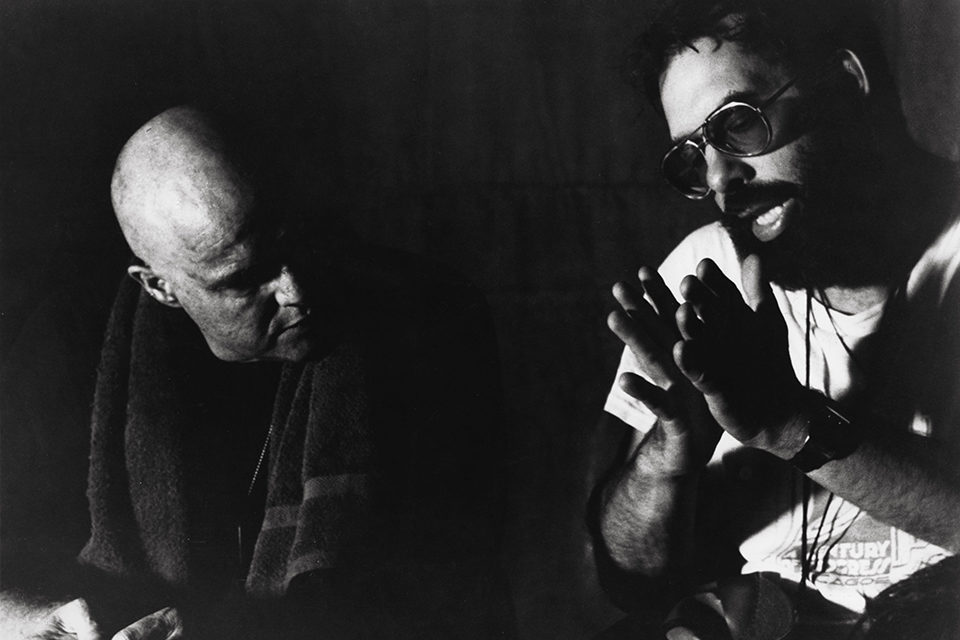

Marlon Brando and Francis Ford Coppola on the set of Apocalypse Now, 1979.

In purely visual terms, every Coppola movie, from the Godfathers to Jack, is an eminently satisfying experience. The full measure of people and objects is always felt within the expanse of the frame and given a tremendous definition, whoever the cinematographer. Besides Walter Murch, Dean Tavoularis seems like the other key collaborator, always performing a superb balancing act between the monumental and the believable. The Godfather films offer one ingeniously organized set piece after another in a series of interiors in which every detail feels at once valid and pushed ever so gently into expressionism. Brando’s lair in the first film is probably too dark for anyone to get any actual work done, but the action is so carefully and subtly orchestrated that it never crosses your mind. One of the most famous scenes in American cinema offers a superb example of Coppola’s favorite move: immersing his viewers in one section of a room or space and then taking them by surprise with a cut to a wider expanse, revealing hitherto unseen onlookers. The briefing lunch in Apocalypse Now offers a more complex but equally fluid variant, shifting between close-ups of exotic food and sweaty faces, the distance between people kept ominously ambiguous. All this intricate spatial diversity gets a lift from Murch’s gift for building up off screen mysteries with his delicate soundtracks.

Coppola is a wizard with camera distance, and he always gets fresh, surprising angles and perspectives on any scene. Right from the start, he was light-years beyond the old master shot/medium/close-up structure, zeroing in on the dramatic possibilities of any given space. The Rainmaker may be a modest liberal melodrama, but every scene is rich in wonders. The outdoor deposition is a beauty, deftly juxtaposing viewpoints and moods in a few minutes of screen time. The details are superb: Danny Glover’s courtly judge greeting all the participants and ushering them into a believably run-down backyard; the team of million-dollar lawyers led by Jon Voight trudging through the mud and unkempt grass in their expensive shoes; a gnatlike Danny DeVito setting up his video camera, and Matt Damon’s touching formality as he introduces his cancer-ravaged client to the assembled crowd. The most surprising moment comes when Coppola cuts to a fresh angle on the silent father crossing the yard past the meeting and hiding out in his abandoned car. For a payoff, almost any other director would milk the dying client vs. arrogant insurance company lawyers for all it was worth. Coppola gives you just a sliver of confrontation and then discreetly finishes the scene off with some comic relief: DeVito going to the fence and offering his card to a nine-year-old with a broken arm.

Coppola’s other strong suit has always been his novelistic gift for telling character traits and juicy situations inspired by events of the recent past (the Watergate hearings, the mysterious death of Pope John Paul I, the manic flurry of corporate takeovers) coupled with casting choices that rival Renoir in audacity. Casting Mickey Rourke as a flamboyant Memphis ambulance chaser is a stroke of genius; putting him in a turquoise suit with a white belt is nothing short of divine inspiration. The same goes for Michael Corleone’s sugar diabetes attacks in The Godfather Part III, Colonel Kilgore’s surfing mania in Apocalypse Now, a leather-skinned Roy Scheider, in the plushest baby blue cardigan, as an out-of-touch insurance magnate in The Rainmaker, the petty practical jokes and rivalries among the surveillance experts in The Conversation, or James Caan’s brain-damaged former football star paying an uncomfortable visit to his old girlfriend in The Rain People. Coppola always peoples his films with a wide variety of personality types and eccentrics, and every performer gets their moment to shine, flavoring the dish with another spice. Tom Waits may not be doing much real acting in Rumble Fish or The Cotton Club (on the other hand, he’s doing a whole lot of it in Dracula), but his languid presence, lanky body, and drawling voice certainly jolt your attention. The Cotton Club offers James Remar’s snarling, four-dimensional Dutch Schultz (he’s like a Bacon painting in motion), the wonderfully old-fashioned vaudeville team of Bob Hoskins and Fred C. Gwynne, Diane Lane and Lonette McKee as luscious (and lustrous) objects of contemplation, a team of the world’s greatest tap dancers, and, most excitingly of all, Joe Dallesandro and Julian Beck as dangerous hoods. And it’s amazing to consider that the sweep of The Godfather Part II contains Joe Spinell’s relaxed hit- man (“Yeah, that’s right senator—there were a lotta buffers”), Gastone Moschin’s cheek-pinching Don, Michael V. Gazzo’s lovable Frankie Pentangeli, Lee Strasberg’s crafty Hyman Roth (“We’re bigger than U.S. Steel”), and the great G.D. Spradlin’s pitch-perfect Senator Pat Geary. And that’s not to mention that vast array of wordless walk-ons or bit players, all of them spot on: the businessmen passing around that gold telephone, the bandleader at Anthony’s first communion extravaganza, Michael’s silent Sicilian bodyguard, Frankie’s old world brother. At times, you get the feeling that Coppola would be content to make a movie that was nothing more than an endless parade of scintillating character types and juicy situations. His collected works resemble a megalopolis of fragile, lonely souls of all shapes, sizes, and inclinations.

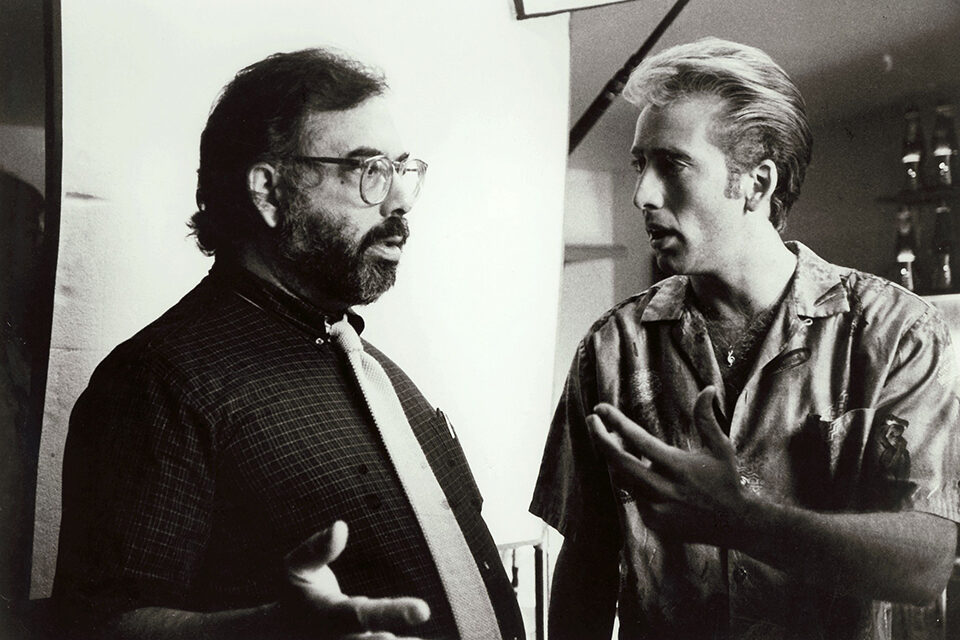

Francis Ford Coppola and Nicolas Cage on the set of Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986)

Coppola’s career is like no other in the history of the cinema, in the sense that it contains five films—one trilogy, one deep plunge into paranoia, and one all-consuming epic —that overshadow everything else. And in a very real sense, those films, four of which were made in a row, are all of a piece. Orson Welles’s career offers an interesting correlative, or maybe a mirror image. The Welles/Coppola connection has been pointed out often enough, and the connections are obvious—two boy geniuses with mercurial personalities and talent to burn, a precocious command of the medium, and a shared penchant for low-angled, monumental imagery, not to mention the Heart of Darkness thing. But whether by accident or design, Coppola’s career seems, in retrospect, like a form of revenge on behalf of Welles, as well as a corrective to his more self-destructive tendencies. All the directors of Coppola’s generation had the example of Welles’s career to look to, something to be at once emulated (for its artistry) and avoided (for its failures). Welles’s tug of war with his own success was writ large by Coppola, who built, ran, and crashed his own electric train, but who, in the process, put the concept of the American auteur on the map. The films made in the shadow of his great work are at once more flamboyant and more modest than Welles’s smaller conceptions, and in many cases more dramatically at war with themselves: where movies like Othello and Chimes at Midnight are stitched together spectacularly, The Cotton Club and Dracula are movies begging to be allowed to fall apart. The former is a gorgeous collection of scenes with a hollow center and a knockout cornball ending (it may be the most visually beautiful film Coppola’s ever made), while the latter is an insane free-for-all in which Coppola perversely throws his rhythmic gifts to the four winds and lets everything on the stove boil over and burn to a crisp. Rumble Fish is probably his Lady from Shanghai, a wealth of feeling mined from a potentially routine project. There are plenty of correlatives to The Stranger, of which The Rainmaker is the best, the most disciplined and moving.

And the combination of the first two Godfathers with Apocalypse Now is his Citizen Kane (The Conversation and The Godfather Part III could be considered addendums). But where Welles’s film remains a difficult, mysterious object, the Coppola films are undeniable, their shared vision belonging not to one man but to everyone. They are popular masterpieces, like Children of Paradise or Open City or The Big Parade, but on a scale at once grander yet more nuanced and intimately detailed than anyone could ever have imagined possible in the cinema. Any country that could elect both Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush president is obviously addicted to myths, and Coppola was the first to take on the enormous task of giving form to two great postwar American mythical abstractions—Family and Vietnam, both quagmires, both horror-inducing. Viewed from afar, his body of work is a cornucopia of physically immediate, powerfully resonant exchanges, images and passages: Fredo asleep in his black satin sheets next to his sluttish wife, getting a midnight call from Hyman Roth’s Sicilian messenger boy; plain old Harry Caul, in his dumpy raincoat, trying to connect with Cindy Williams as he walks alongside her in a dream (“He’d kill you if he had the chance”); Aurore Clement wrapping herself in white muslin and dissolving into the mist; an archbishop falling from a vast ceiling within the Vatican, his robes fluttering as he goes. The moments I treasure the most in Coppola’s cinema involve men and their brothers. Matt Dillon taking one last, rhapsodic ride with Mickey Rourke and hugging him for dear life, in Rumble Fish. And in The Godfather Part III, a film of variable parts that nonetheless adds up to a majestic whole, there’s Pacino’s impromptu confession to the future pope in a church courtyard, following a diabetic attack. The beauty of the scene has to do with the hollow, echoing sounds of hushed voices reverberating against ancient stones, and Pacino’s slack body in disarray, recovering his equilibrium with a glass of orange juice and a candy bar. And then there’s the confession itself, at which point Coppola cuts to a discreet angle that leaves Pacino protected and secure by the wall and the vine leaves: “I killed my father’s son. I killed my mother’s son.” The cardinal advises him that his sins are terrible and his suffering is just, but that he can be redeemed whether he believes it or not. “Ego te absolvo…”. It’s a surpassingly beautiful moment, as both a high point of one of the most magnificent actor/director collaborations in movies, and also for the way it leaves Michael Corleone more alone than he’s ever been, with the possibility that he will be deserted forever by his own guilt. There’s nothing else quite like it.

Beneath the mask of the impresario beats the loneliest heart in cinema.

Kent Jones is Film Comment’s editor-at-large.