My Three Powerfully Effective Commandments

Experience should be gained before one reaches forty, so a wise man has said. After forty it is permissible for one to comment.

I venture to say that the reverse might apply in my case. No one under forty was more certain of his theories and no one more willing to elucidate them than I was. No one knew better or could visualize more.

But now that I am somewhat older I have become rather more cautious. The experience that I have gained, and which I am still sorting out, is of such a kind that I am unwilling to express myself on the art of the filmmaker. I know for a fact that my work involves technical skill and mental ability, but I know, too, that even my greatest experience will be uninteresting to others, except perhaps to the potential filmmaker.

Moreover, it is my opinion that an artist’s work is the only real contribution that he can make to a critical discussion of art. Thus I find it rather unseemly to get involved in such discussion, even with explanations or excuses.

No, the fact that the artist remained unknown was a good thing in former times. His relative anonymity was a guarantee against irrelevant outside influences, material considerations and the prostitution of his talents. He brought forth his work in spirit and truth as he saw it, and he left the judgment to the Lord. Thus he lived and died without being more or less important than any other artisan. Eternal values, immortality and masterpieces were terms not applicable in his case.

His work was to the glory of God. The ability to create was a gift and an accomplishment. In such a world there flourished natural assurance and invulnerable humility—two qualities that are the finest hallmarks of art.

But in life today the position of the artist has become more and more precarious; the artist has become a curious figure, a kind of performer or athlete who chases from job to job. His isolation, his now almost holy individualism, his artistic subjectivity, can all too easily cause ulcers and neurosis. Exclusiveness becomes a curse that he eulogizes. The unusual is both his pain and his satisfaction.

It is possible that I have made a general rule from my own idiosyncrasies. But it is also possible that the conflict of responsibility has been intensified and the moral problems made so difficult because of dependence on popular support and also due to unreasonable economic burdens.

Anyway, I now find that I need to clarify what I have been thinking, what my standards are and what constitutes my position. This will be a personal and not an authoritative pronouncement on film art, with some quite subjective notes on the technical and ethical problems of the filmmaker.

Script

Often it begins with something very hazy and indefinite—a chance remark or a quick change of phrase, a dim but pleasant event, yet one that is not specifically related to the actual situation . It can be a few bars of music, a shaft of light across the street. It has happened in my theatrical work that I have seen performers in fresh make-up in yet unplayed roles.

All in all these seem to be split-second impressions that disappear as quickly as they come, yet nevertheless leave an impression behind just like a pleasant dream.

Most of all they are a brightly colored thread sticking out of the dark sack of the unconscious. If I begin to wind up this thread and do it carefully, a complete film will emerge.

I would like to say that this is not a case of Pallas Athene in the mind of Zeus, but an unconnected phenomenon, more a mental state than an actual story, but for all that abounding with fertile associations and images.

All this is brought out with pulse-beats and rhythms that are very special and characteristic of the different films. Through these rhythms the picture sequences take a separate pattern, according to the way they were born and mastered by the motive.

This primitive life-cell strives from the beginning to achieve form, but its movements may be lazy and perhaps even a little drowsy. If in this primitive state it shows itself to have enough strength to transform itself into a film, I then decide to give it life, and I begin work on the script.

The feeling of failure occurs mostly before the writing begins. The dreams become merely cobwebs; the visions fade and become grey and insignificant; the pulse-beat is silent; feelings become small, tired fancies without strength and reality.

I have thus decided to make a certain film, and now begins the complicated and difficult mastered work—to transfer rhythms, moods, atmosphere, tensions, sequences, tones and scents into words and sentences in a readable or at least understandable script.

This is difficult but not impossible.

The vital thing is the dialogue, but dialogue is a sensitive matter that can offer resistance. We have learned (or should have learned) that the written dialogue of the theater is like a score that is almost incomprehensible to the ordinary person. Interpretation of theatrical dialogue demands a technical skill and a certain amount of imagination and feeling, qualities so often lacking in the theatrical profession.

One can write dialogue, but the directions on how the dialogue should be handled, the rhythms and the tempo, the speed at which it is to be taken, and what is to take place between the lines—all that must for practical reasons be left out because a script containing so much detail would be unreadable.

I can squeeze directions and locations, characterizations and atmosphere into my film—scripts in understandable terms, provided I am a tolerable writer and the reader has a fair reading ability, which is not always the case.

However, I now come to essentials, by which I mean montage, rhythm and the relation of one picture to the other—the vital “third dimension” without which the film is merely a dead product of a factory. Here I cannot give “keys” or an adequate indication of the empos of the complexes involved, and it is quite impossible to give a comprehensible idea of what gives life to a work of art. I have often sought a kind of notation that would give me a chance of recording the shades and tones of the ideas and the inner structure of the picture.

(Thus let us state once and for all that the film-script is a very imperfect technical basis for a film.)

In this connection I should draw attention to another fact that is often overlooked. Film is not the same thing as literature. As often as not the character and substance of the two art forms are in conflict. What this difference really depends on is hard to define but it probably has to do with the self-responsive process. The written word is read and assimilated by a conscious act and in connection with the intellect, and little by little it plays on the imagination or feelings. It is completely different with the motion picture. When we see a film in a cinema we are conscious that an illusion has been prepared for us, and we relax and accept it with our will and intellect. We prepare the way into our imagination. The sequence of pictures plays directly on our feelings without touching the mind. There are many reasons why we ought to avoid filming existing literature, but the most important is that the irrational dimension, which is the heart of a literary work, is often untranslatable, and that in its turn kills the special dimension of the film. If, despite this, we wish to translate something literary into filmic terms, we are obliged to make an infinite number of complicated transformations—which most often give limited or no result in relation to the efforts expended.

I know what I am talking about because I have been subjected to so-called literary judgment. This is about as intelligent as letting a music critic judge an exhibition of paintings or a football reporter criticize a new play.

The only reason for any and everyone believing himself capable of pronouncing a valid judgment on motion pictures is the inability of the film to assert itself as an art form, its need of a definite artistic vocabulary, its extreme youth in relation to the other arts, its obvious ties with economic realities, its direct appeal to the feelings. All these factors cause the motion picture to be regarded with disdain. The directness of expression of the motion picture makes it suspect in certain eyes, and as a result any and everyone thinks himself competent to say anything he likes in whatever way he likes on film art.

I myself have never had ambitions to be an author. I do not wish to write novels, short stories, essays, biographies or treatises on special subjects. I certainly do not want to write plays for the theater. Film-making is what interests me. I want to make films about conditions, tensions, pictures, rhythms and characters within me and that in one way or another interest me. I am a film-maker, not an author. The motion picture is my medium of expression, not the written word. The motion picture and its complicated process of birth are my methods of saying what I want to my fellow men. I find it humiliating for my work to be judged as a book when it is a film. It is like calling a bird a fish, and fire, water.

Consequently the writing of the script is a difficult period, but it is a useful one as it compels me to prove logically the validity of my ideas. While this is taking place I am caught in the difficult conflict of situations. There is a conflict between my need to find a way of filming a complicated situation and my desire for complete simplicity. As I do not intend my work to be solely for the edification of myself or for the few but instead for the public in general, the demands of the public are imperative. Sometimes I try a daring alternative, and it has been shown that the public can appreciate the most advanced and complicated developments.

For a very long time I have wanted to use the film medium for story-telling. This does not mean that I find the narrative form itself faulty, but that I consider the motion picture ideally suited to the epic and the dramatic.

I know, of course, that by using film we can bring in previously unknown worlds, realities beyond reality.

It is of great importance for our long-suffering industry to produce fine dreams, light frolics, germs of ideas, brilliant dazzling bubbles.

I do not say that these things never materialize, only that they are all too infrequent and all too half-hearted.

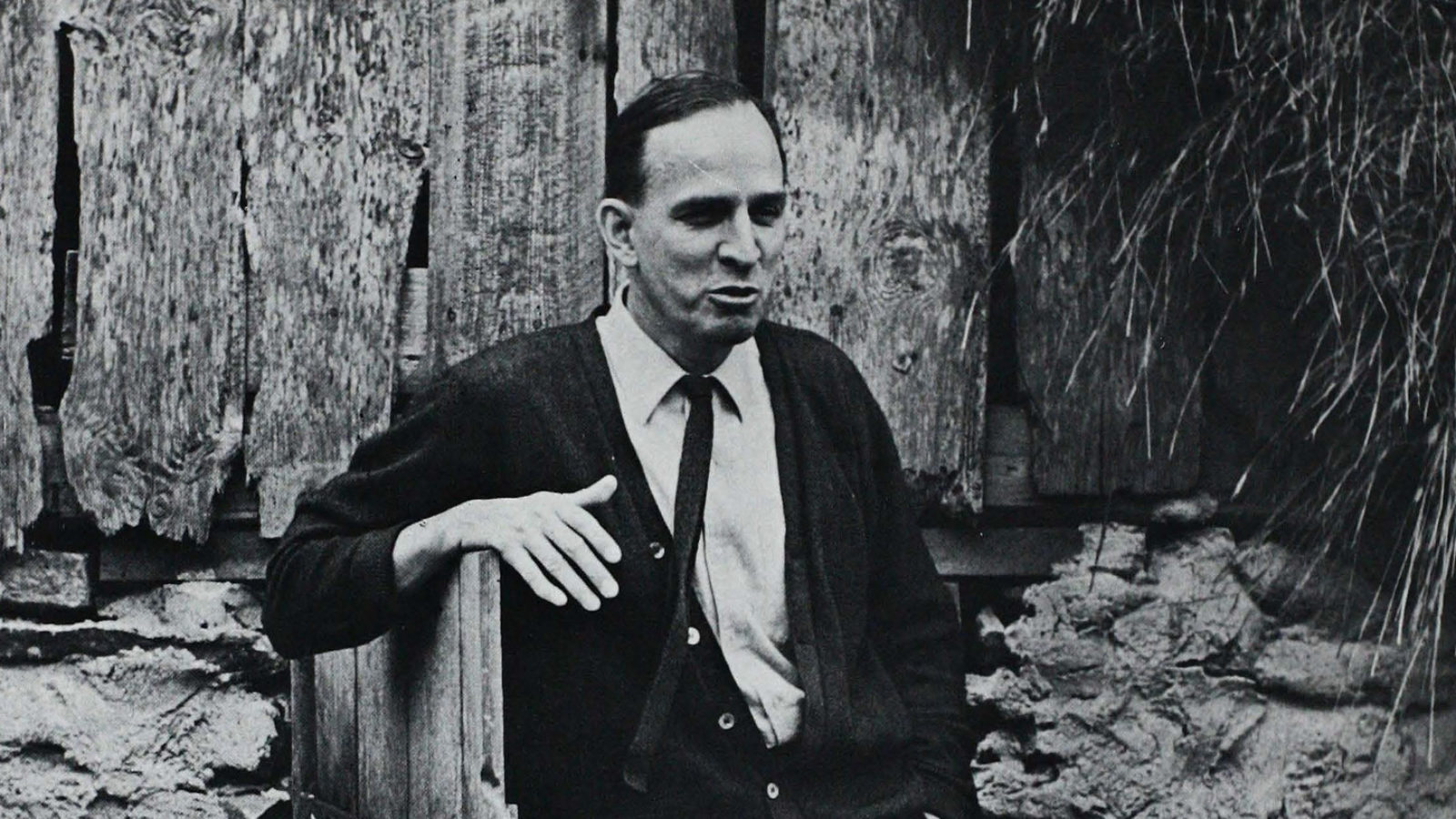

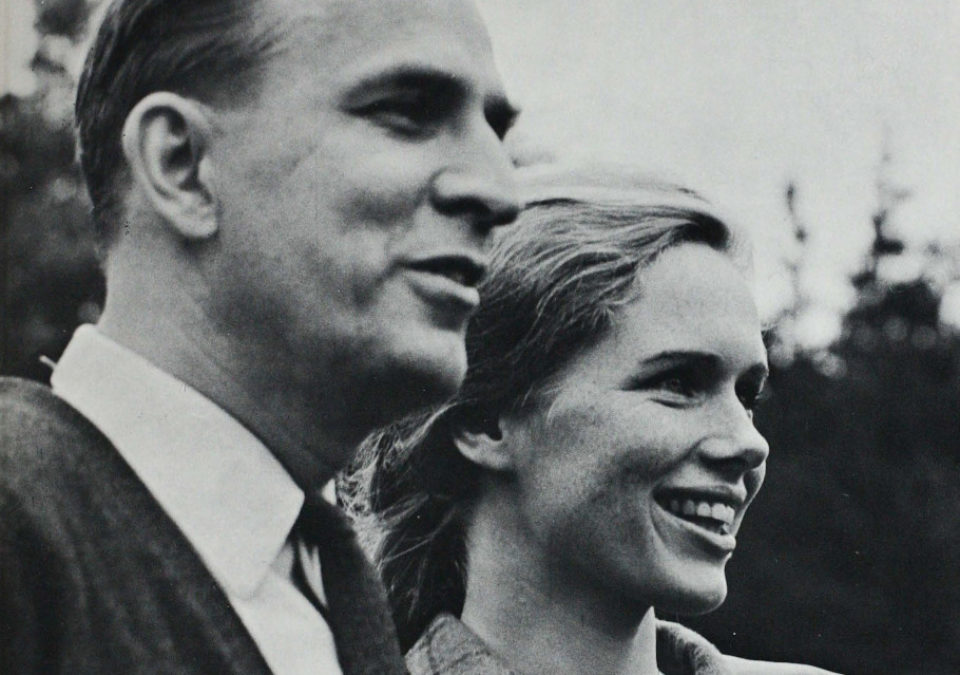

Ingmar Bergman and Liv Ullmann

Studio

It happens when I stand there in the half-light of the film studio with its noise and throng, the dirt and wretched atmosphere, I seriously wonder why I am engaged in this most difficult form of artistic creation.

The rules are many and burdensome. I must have three minutes of usable film “in the can” every day. I must keep to the shooting schedule, which is so tight that it excludes almost everything but essentials. I am surrounded by technical equipment that with fiendish cunning tries to sabotage my best intentions. Constantly I am on edge, I am compelled to live the collective life of the studio. Amidst all this must take place a process that is sensitive and that really demands quietness, concentration and confidence.

I mean: working with actors and actresses.

There are many directors who forget that our work in films begins with the human face. We can certainly become completely absorbed in the aesthetics of montage, we can bring together objects and still-life into a wonderful rhythm, we can make nature studies of astounding beauty—but the approach to the human face is without doubt the hallmark and the distinguishing quality of film. From this we might conclude that the film star is our most expensive instrument and that the camera merely registers the reactions of this instrument. In many cases the opposite can be seen: the position and movement of the camera is considered more important than the player, and the picture becomes an end in itself. But this can never do anything but destroy illusions and be artistically devastating.

In order to give the greatest possible strength to the actor’s expression, the camera movement must be simple, free and completely synchronized with the action. The camera must be a completely objective observer and only on rare occasions may it participate in the action.

We should realize that the best means of expression the actor has at his command is his appearance. The close-up, if objectively composed, perfectly directed and played, is the most forcible means at the disposal of the film director, while at the same time it is the most certain proof of his competence or incompetence. The lack or abundance of close-ups shows in an uncompromising way the nature of the film director and the extent of his interest in people.

Simplicity, concentration, full knowledge, technical perfection must be the pillars supporting each scene and sequence.

However, in themselves they are not enough.

All these factors exist—and it is necessary for them to do so—but still the one most important element is lacking, the spark that brings the whole thing to life. This intimate spark of life appears, or fails to appear, according to its will. This spark of life is crucial and indomitable.

For instance, I well know that everything for a scene must be prepared down to the last detail, each branch of the collective organization must know exactly what it is to do. The entire mechanism must be free from fault as a matter of course. These preliminaries mayor may not take a long time, but they should not be dragged out and tire those participating. Rehearsals for the take must be carried out with technical precision, with everyone knowing exactly what he is to do.

Then comes the take. From experience I know that the first take is often the happiest as it is the most natural. This is because with the first take the actors are trying to create something; this creative urge provides a spark of life and comes from natural identification. The camera registers this inner act of creation, which is hardly perceptible to the untrained eye or ear but which is recorded and preserved on the sensitive photographic film and on the sound-track.

I believe it is precisely this sudden act of creation by an actor that keeps me in films and holds me fascinated with the medium. The development and retention of a sudden burst of life gives me ample reward for the thousands of hours of grey gloom, trial and tribulation.

The actor must unconditionally identify himself with his part. This identification should be like a costume that is slipped on. Lengthy concentration, continuous control of feelings and high-pressure working are completely out. The actor must be able in the purely technical sense (and if possible with the director’s help) to take on and take off the character he is playing. Mental tensions and lengthy exertions are fatal to all filmic expression.

The director should not deluge the actor with instructions like autumn rain, but rather he should make his points at the right moments. His words should be too few rather than too many. For his performance the actor is little helped by the director’s intellectual analysis. What the actor wants are exact instructions at the moment and certain technical corrections without embellishments and digressions. I know that an intonation, a look or a smile from the director can often do far more good to the actor than the most penetrating analysis. This mode of directing sounds like witchcraft, but it is nothing of the sort; it is only a quiet and effective method of control over the actor by his director. Indeed, the fewer the discussions, talks and explanations, the more the affinity, silence, mutual understanding, natural loyalty and confidence.

Morality

Many imagine that a commercial film industry lacks morality or that its practices are so definitely based on immorality that an artistically ethical standpoint cannot be maintained. Our films are assigned to businessmen, who at times regard them with apprehension, as motion pictures have to do with something as unreliable as art.

If many may regard our activity as dubious, I must emphasize that its morality is as good as any and so absolute that it could almost cause us embarrassment. However, I have found that I am like the Englishman in the tropics who shaves and dresses for dinner every day. He does not do this to please the wild animals but for his own sake. If he gives up his discipline then the jungle has beaten him.

I know that I shall have lost to the jungle if I take a weak moral standpoint or relax my mental punctiliousness. I have, therefore, come to a certain belief that is based on three powerfully effective commandments. Briefly, I shall state their wording and their meaning. These have become the very fundamentals of my activity in the film world.

The first may sound indecent but really is highly moral. It runs:

THOU SHALT BE ENTERTAINING AT ALL TIMES.

This means that the public that sees my films and thus provides my bread and butter has the right to expect entertainment, a thrill, a joy, a spirited experience. I am responsible for providing that experience. That is the only justification for my activity.

However, this does not mean that I must debase my talents, at least not in any and every way, because then I would break the second commandment, which runs:

THOU SHALT OBEY THY ARTISTIC CONSCIENCE AT ALL TIMES.

This is a very tricky commandment because it obviously forbids me to steal, lie, prostitute my talents, kill or falsify. However, I will say that I am allowed to falsify if it is artistically justified, I may also lie if it is a beautiful lie, I could also kill my friends or myself or anyone else if it would help my art, it may also be permissible to prostitute my talents if it will further my cause, and I should indeed steal if there were no other way out.

If one obeyed one’s artistic conscience to the full in every respect then one would find oneself doing a balancing act on a tight-rope, and one would become so dizzy that at any moment one could fall down and break one’s neck. Then all the prudent and moral bystanders would say: “Look, there lies the thief, the murderer, the lecher, the liar. Serves him right.” Not a thought that all means are allowed except those which lead to a fiasco, and that the most dangerous ways are the only ones that are passable, and that compulsion and dizziness are two necessary parts of our activity. Not a thought that the joy of creation, which is a thing of beauty and a joy forever, is bound up with the necessary fear of creation.

One can incant as often as one desires, magnify one’s humility and diminish one’s pride to one’s heart’s content, but the fact still remains that to follow one’s artistic conscience is a perversity of the flesh as a result of years and years of mortification and radiant moments of clear asceticism and resistance. In the long run it is the same, however we reckon. First, on the point of fusion, comes the area between belief and submission, which can be called the artistic obvious. I wish to assert at this point that this is by no means my only goal, but merely that I try to keep to the compass as well as I can.

In order to strengthen my will so that I do not slip off the narrow path into the ditch, I have a third good and juicy commandment, which runs:

THOU SHALT MAKE EACH FILM AS IF IT WERE THY LAST.

Some may imagine that this commandment is an amusing twist of word-play or a pointless aphorism or perhaps simply a beautiful phrase about the complete vanity of everything. However, that is not the case.

It is reality.

In Sweden film production was interrupted for a whole year some years ago. During my enforced inactivity, I learned that because of commercial complications, and through no fault of my own, I could be out on the street before I knew it.

I do not complain about it, neither am I afraid or bitter; I have merely drawn a logical and highly moral conclusion from the situation: that each film is my last.

For me there is only one loyalty—that is my loyalty to the film on which I am working. What comes (or fails to come) after is insignificant and causes neither anxiety nor longing. This attitude gives me assurance and artistic confidence. The material assurance is apparently limited but I find that artistic integrity is infinitely more important. Therefore I follow the principle: each film is my last.

This conviction gives me strength in another way. I have seen all too many film workers burdened down with anxiety, yet carrying out to the full their necessary duties. Worn out, bored to death and without pleasure, they have fulfilled their work. They have suffered humiliation and affronts from producers, the critics and the public without flinching, without giving up, without leaving the profession. With a tired shrug of the shoulders, they have made their artistic contributions until they went down or were thrown out.

I do not know but perhaps the day will come when I shall be received indifferently by the public, perhaps together with a feeling of disgust in myself. Fatigue and emptiness will descend upon me like a dirty grey sack, and fear will stifle everything. Emptiness will stare me in the face.

When this happens I shall put down my tools and leave the scene, of my own free will, without bitterness and without brooding whether or not the work has been useful and truthful from the viewpoint of eternity.

Wise and far-sighted men in the Middle Ages used to spend nights in their coffins in order never to forget the tremendous importance of every moment and the transient nature of life itself.

Without taking such drastic and uncomfortable measures, I harden myself to the seeming futility and the fickle cruelty of film-making, with the earnest conviction that each film is my last.

This article was translated from Swedish by P. E. Burke and Lennart Swahn.