Murnau’s Midnight and Sunrise

The following essays on NOSFERATU and SUNRISE, together with the essay on TABU already published in FILM COMMENT (Summer 1971), date in their original form from 1970-1. They were conceived as the basis for a book on Murnau (actually promised when the TABU piece appeared). Two factors delayed further work on the book: 1. First the American, then (as a direct consequence) the British publisher withdrew when the great film book slump started; 2. With so many of Murnau’s films lost or inaccessible, I hoped at least to cover all his Hollywood work, and there were repeated rumors of the survival of a print of THE FOUR DEVILS, which was imminently expected to re-surface.

Ironically, when I at last found a publisher a year or so ago, I realized that I no longer wanted to write the book. Reading over my material, it seemed (with a number of revisions I have now made) complete, though not of course as a definitive work on Murnau. I felt no desire at all to produce a “scholarly” work that would cover all the available films. Within the surviving canon, NOSFERAW, SUNRISE, and TABU seem to me, though made in different parts of the world, against very different cultural backgrounds, and over a period of almost ten years, to form a single complex text based on the permutation (eventually, the inversion) of a recurrent structural pattern: a united heterosexual couple threatened by a sinister, partly mysterious, usually male, figure.

That pattern recurs in other Murnau films too (TARTUFFE, FAUST, CITY GIRL) but not with quite the same resonances. TARTUFFE is interesting for the way in which Murnau converts hypocrite into a figure of great power and repressed sensual energy; FAUST is interesting for the fact that the threatening figure there becomes literally the Devil (though Jannings’s unwatchable amateur-night-at-the-opera performance deprives it of all resonance); CITY GIRL is most interesting for the fact that there the threatening figure becomes literally the Father (a point that might become crucial in a strictly psychoanalytic reading of the films). Yet none of these manifestations adds significantly to the overtones and implications present in my Murnau “trilogy,” and none of these other films (though CITY GIRL, at least, is splendid) carries quite the same aura of suggestion. They do, however, underline and confirm the strange process whereby the threatening figure is transformed from Id (NOSFERATU, FAUST, SUNRISE) to Superego (CITY GIRL, TABU).

In my work on Murnau I was greatly helped and encouraged by my then wife, Aline; the films meant a lot to us personally. I dedicate these essays to her, with gratitude and affection.

NOSFERATU

It is difficult to talk other than tentatively about the work of F. W. Murnau. He directed twenty-two films, of which a number are apparently lost. Of the remainder, all but a few exist only in prints in inaccessible archives. But three of the films still in intermittent circulation seem to me among the cinema’s great achievements—which is why it is necessary to make some attempt at discussing Murnau despite the handicaps.

NOSFERATU, SUNRISE, and TABU are not merely remarkable individually. One senses between them a fascinatingly complex relationship of likeness and opposition. The three are widely separated in time and space: Murnau shot NOSFERATU, his tenth film, in Germany in 1922, SUNRISE in Hollywood in 1927, TABU in the Pacific islands in 1930 (it was his last film). Oddly, it is NOSFERATU and TABU, the furthest separated in time, that reveal at once the deepest affinities and the strongest contrasts.

What, in simple terms, have these three obviously very different films in common? SUNRISE and TABU are easy to relate in that both are single-mindedly concerned with the couple, with the sense of the marriage relationship as having prime and central significance in human life. Beyond this, both films share what one might call the Romantic attitude to nature—a life close to nature, based on “natural” simplicities, being upheld against the corruption and artificiality of the City (SUNRISE) and of white civilization (TABU)—though nature in both films is shown to have a dark, terrible aspect beneath its surface appearance of sunshine and health. But NOSFERATU is an early version of DRACULA, antedating Tod Browning and Terence Fisher; its most striking, and apparently central, figure is the vampire Count; the film is for the most part a fairly straight retelling of Bram Stoker’s familiar narrative that for most people nowadays, at first viewing anyway, seems to live (if at all) by virtue of certain arresting images and compositions, of which the shot of Nosferatu against sky and rigging from the hold of the ship, may stand as an example. What has such a horror-fantasy to do with universal concepts like “nature” and “the couple”? The answer is, in Murnau’s hands, everything.

The introductory caption might alert us to what is essential in the film: it mentions the Bremen plague, then tells us that “at its origin and its climax were the innocent figures of Jonathan Harker and his young wife Nina.” I am going to argue that in NOSFERATU we have one of the cinema’s finest and most powerfully suggestive embodiments of what I call the “Descent myth”—one of those universal myths that seem fundamental to human experience. Reduced to its simplest essentials, the Descent myth shows characters existing in a state of innocence who by a process of (often literal) descent are led to discover a terrible underlying reality of whose existence they had scarcely dreamed. They either are destroyed by the experience or emerge from it sadder and wiser.

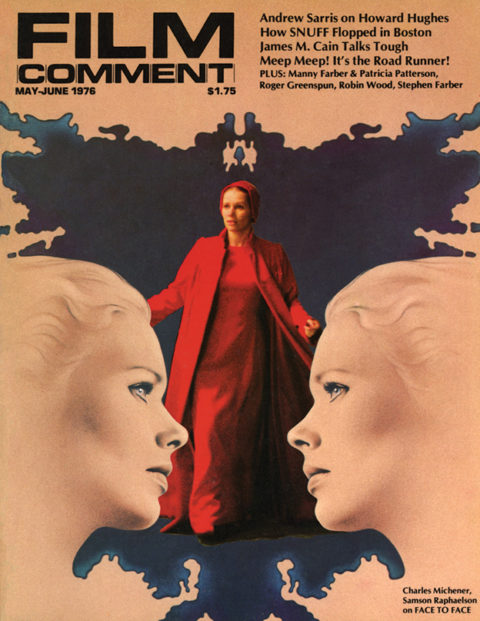

The myth is perhaps fundamental to all civilized existence, suggesting the darker depths beneath our civilized appearances; it also has an odd and ambiguous connection with the Garden of Eden myth. The classic Greek rendering is the myth of Persephone, where it is linked to nature and the seasons, with the Orpheus myth as a variant. But the main lines of the myth recur repeatedly in Western culture and probably in all cultures. In English literature one of its supreme embodiments (as my reference above will have suggested) is The Ancient Mariner; but its presence is at least equally striking in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In the cinema it can be seen as activating much of Hitchcock’s work, PSYCHO is one of the great Descent films. Recent Bergman, especially PERSONA and FACE TO FACE, can be explored in relation to such a myth. It is common in fairy tales and horror films; its outlines can be discerned, in an emasculated form, lurking in the background of CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG; its most powerful recent embodiment is in Gary Sherman’s DEATH LINE (or RAW MEAT, as the mutilated American release version was retitled).

The vampire myth and Bram Stoker’s development of it easily coalesce with the Descent myth. Indeed, it could be argued that almost everything I am seeking to demonstrate in NOSFERATU is inherent in vampire mythology. Yet this in no way diminishes the film’s stature. Through the power and suggestiveness of his imagery, Murnau really does justice to the rich potentialities of material that (with the notable exception of Dreyer’s VAMPYR) has generally been merely debased and exploited. It is the quality of the director’s response to his material that matters, and I am not concerned with the precise degree to which Murnau was conscious of the implications his film can be seen to have. NOSFERATU remains itself a myth, with figures who are more archetypes than psychologically rounded characters; Murnau doesn’t himself seek to explain the myth, but to embody it in images. What I am forced for the sake of clarity to spell out is, in the film, a matter of suggestive resonances arising from the intensity with which Murnau feels his material, rather than clear-cut allegory.

When Persephone was carried off by Pluto, the god of the underworld, she was gathering flowers in the spring meadows. NOSFERATU begins with Jonathan gathering flowers for his wife—whom we first see leaning over a flower-filled window-box to play with a kitten. Murnau very simply establishes an innocent, almost over-sweet, idyllic relationship—though even at the outset a distinction is suggested between the two characters: the young man seeming complacent and over-confident, while a look of sadness and tenderness comes over Nina’s face as he gives her the flowers. Jonathan is sent to negotiate a property sale, and early in the film we are shown the house in question, a great derelict building evoking decay and desolation. It is immediately opposite Jonathan and Nina’s house—like a mirror, but a mirror in which there is as yet no dearly defined reflection; its position is made much of, visually, in the film’s climactic sequences.

Nature is the real subject of NOSFERATU. The “nature” suggested by Nina’s flowers—the daytime nature of sunlight and harmony—is referred to at several points as the film progresses: in the shots of horses moving across a hillside in early morning sunshine, in the shots of the sea sparkling in the sun. But behind this, as it were, is the night-time nature, the terrible underworld into which Jonathan descends and whose forces he releases. Nosferatu is consistently associated with nature throughout the film. His castle, on its first appearance, is like a natural continuation of the rock, an outcrop. He is identified with the jackal prowling the woods at night—the jackal that startles and unsettles the horses—during the scene at the inn where the landlord warns Jonathan against continuing his journey. Nosferatu’s first appearance suggests a nocturnal animal emerging from its lair (the cave-like vault). His movements are not those of a human being; he seems to move silently, with a skulking, sidling motion. His ears are long and pointed, and have hair growing on them; his hands and fingernails are like talons or claws; his teeth are fangs.

This “nature” motif is taken up more explicitly elsewhere in the film, notably in Professor von Helsing’s lecture. The caption tells us that “Professor von Helsing was giving a course on the secrets of nature and their strange correspondences to human life.” The lecture we watch is concerned with the Venus fly-trap and a carnivorous polyp. After it we see Renfield, Nosferatu’s agent in the city, catching and eating flies in his madman’s prison cell; and slightly later he fascinatedly watches spiders devouring their victims in a web. In the sequences of his escape and pursuit Renfield seems to revert to an animal level, swinging down from rooftops like an ape, crouching behind a rotting tree stump, hopping like a frog or toad. These scenes suggest the continuity between the nature the film depicts and human nature—between the exotic Venus Flytrap, the commonplace spider, and Renfield, and by implication between Nosferatu and ourselves.

The film postulates, then, a duality in nature. Below the surface of sunlight, flowers, and innocence, a terrible undernature, precariously repressed, awaits its chance to surge up and take over. Horses (traditionally the friend of man) belong to the daytime nature; and this gives particularly macabre overtones to the sinister hooded horses that draw the vampire’s coach. The transition from the horses that draw Jonathan’s coach from the inn to the vampire’s horses underlines the symbolism of the crossing of bridges: “And when he had crossed the bridge, the phantoms came to meet him.”

Repression imagery dominates the film. Nosferatu emerges from his cave-vault as from under the ground, like a horribly perverted version of D.H. Lawrence’s snake driven down into its dark hole. Then Jonathan descends into the crypts to find Nosferatu’s coffin he passes under a huge oppressive overhang of rock that also forms part of the castle’s structure. The arch is a visual leitmotif in the film. Murnau uses it particularly to characterize the vampire as a repressed force who is always emerging from under arches or arch-shapes that seem to be trying unsuccessfully to press down upon him, often forming a background of darkness. That the image is again inherent in vampire mythology is suggested by its recurrence in most vampire films; the traditional setting of Gothic castle inevitably includes arches in association with the other traditional elements of vaults, crypt, coffin, etc. But Murnau’s compositions with arches have such striking pictorial force that few will question the validity of finding a more than incidental (though not necessarily fully conscious) significance in them.

The arch is used also to link Nosferatu with Jonathan. There is an arch over the bed in which Jonathan sleeps in the inn—the first effectual appearance of the image, as he nears the vampire’s domain. At their first meeting, Nosferatu emerges from one arch, Jonathan from another, as if he were walking out to meet his reflection. The scene ends with Nosferatu leading the young man down into the darkness of his arched vault—a perfect “descent” image, and one that in its context calls to mind the descent of Cocteau’s Orpheus into the underworld via mirrors (i.e., a descent into himself). At the end of the dinner scene, where Nosferatu is roused by the blood from Jonathan’s cut finger, the arch-structure is very like that from which he first emerged, an alternate patterning of light and darkness. When Jonathan wakes up the next morning, at sunrise, contemptuously dismissing the marks on his neck as of no significance, he is still beneath an arch-structure formed by the décor and shadows. He walks out into the open through an arched doorway in long-shot, and then under a dark arch that oppressively fills the entire foreground of the image, to write a letter to Nina under the arches of small pavilion. In the letter he again dismisses the marks on his throat and his bad dreams; the Nosferatu-arches comment on his confidence. Jonathan’s movement under a series of arch-shapes here is later “mirrored” in Nosferatu’s nocturnal visit to his bedroom to suck his blood.

The richness of the film’s suggestivity can be seen as the product of a synthesis of a number of traditional or cultural elements fused within the particular sensibility of Murnau: the repressive arches of Gothic fiction and cinema; vampire mythology; the “descent” myth; the notion of the double or Doppelgänger which Lotte Eisner sees as a central motif of Expressionist cinema (“the haunted screen”) but which has obvious antecedents in nineteenth-century literature (Poe’s “William Wilson,” Wilde’s Dorian Gray). Of Murnau’s lost German films, the one that most particularly arouses curiosity (the more so in that it stars the remarkable Conrad Veidt) is DER JANUSKOPF, a version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde that antedates NOSFERATU by two years.

The linking image of the arch is not the only way in which a parallel is established between Jonathan and Nosferatu. I have already suggested that the house opposite, which Jonathan looks at with such fear, is a mirror awaiting a reflection—a gap that will ultimately be filled by the vampire as he stares across beseechingly at Nina. Nosferatu becomes a kind of demonic alternative husband for Nina, whom she must accept with ambiguous desire and revulsion. The explanatory caption to the contrary, it is not Jonathan who “hears” Nina in the scene of telepathic communication when she interrupts Nosferatu’s nocturnal visit to his prey. Jonathan makes no response whatever; it is the vampire who hears Nina, looks up, and moves away, not so much prevented from sucking the man’s blood as distracted by a greater, more necessary pull.

André Bazin’s opinion that “in neither NOSFERATU nor SUNRISE does editing play a decisive part” is even more perverse than his rejection of the view that “the plasticity of Murnau’s images has an affinity with a certain kind of expressionism.” The elaborate intercutting of Jonathan’s and Nosferatu’s journeys, and Nina’s ambiguous expectation, is crucial to the film’s meaning. Jonathan travels by land, the vampire by sea; Nina, awaiting her husband, looks out to sea all the time, from a seashore dotted with crosses that associate her at once with Christian redemption and death. The hero and his released double reach the city simultaneously, Nosferatu scurrying surreptitiously through the shadows with his coffin as Jonathan rides in. Above all, there is the disturbingly weird incident of Nina’s sleepwalking along a parapet, arms outstretched to the darkness. She calls out as she collapses, “He’s coming, I must go to meet him.” But Murnau has cut to this (and the editing seems here to be consistent in all extant versions of the film), not from Jonathan’s ride, but from Nosferatu’s inexorable progress by ship.

Jonathan can’t destroy Nosferatu—can’t even attempt to destroy him. Even when the vampire is lying helpless in his coffin during the daytime, all Jonathan can do is recoil in horror. Significantly, it seems to be Jonathan’s impotence that gives Nosferatu the power and freedom to leave his environment, shut away from civilization in inaccessible forests and wilds, to rise and spread like a pestilence over the civilized world. Only after Nosferatu has been released in this way can Jonathan summon up his forces for pursuit and combat—though in fact he never does provide any effective opposition to the vampire. Near the end of the film, when Nina makes Jonathan look at the house opposite and begins to tell him, “Every night, in front of me . he can again do nothing but recoil helplessly and collapse on the bed. He seems not to want to know what Nina sees clearly.

From the moment of Nosferatu’s release, Murnau emphasizes the growth of his power. The ship is consistently photographed in ways evoking power, sweeping across the screen so that, instead of being neatly framed and “fixed,” it seems to burst into and out of the image; or with the camera on deck behind the prow as it pushes ahead through the waves. At first the ship is guided and controlled by normal human means, normal human consciousness, with Nosferatu hidden away in the hold in his coffins, an unknown presence (the repression motif again). Earlier, the supernaturally opening door—no catch and no lock—into Jonathan’s chamber resembled a coffin lid, with the vampire exactly fitting the door space like a body in a coffin; the resemblance links the film’s main repression images, the door having the characteristic arch-shape. Gradually, on the ship, the vampire rises up and takes over, undermining and destroying the whole crew, until the ship has become an extension of his power, supernaturally propelled by his mysterious energies. The culminating image here is the one I have already alluded to: Nosferatu, filmed from the hold, seeming immensely tall from so low an angle, moving around the deck against a background of sky and rigging. It’s an unforgettable power-image.

The sea and its associations are very important in these scenes. The sea should be a barrier, a protection; our sense of security is undermined by the images of the boat bearing Nosferatu sweeping irresistibly across it. The sea is traditionally associated with purity, or purification (viz. late Shakespeare), and the suggestion of Nosferatu’s power spreading it intensifies our sense of contamination. The inexorability of his progress is conveyed in another unforgettable shot—and one Murnau was to use again with similar effect in TABU—in which the ship glides in from the side of the frame completely to fill an image previously occupied by quiet river and quay and sleeping town. Our sense of Nosferatu’s power is intensified by the fact that the ship is deserted, and is moving without human agency; and by the fact that it is still full-rigged as it slides toward the quay. He enters the town like fate, like a doom.

In the scenes of his progress his identity as a force of nature, or the underworld of nature, is again implied and strengthened. There are the rats with which he is repeatedly associated, swarming out from the black coffin interiors in which they have been breeding in darkness, then out from the hold when the ship is in the city; there is also the plague, with which the rats are connected. The exact nature of the plague is left ambiguous; it is spread by the rats, yet the vampire’s marks are on the victims’ necks, as if Nosferatu had visited each personally. The ambiguity is essential to the film’s symbolism, allowing us to view the plague as the eruption both of universal natural forces and of repressed energies in the individual. In this context the thrice-recurring image of the rats swarming out from their coffined darkness is powerfully evocative.

The plague is a means of universalizing the whole idea of the film. Nosferatu is not only in Jonathan, in the marriage, he is in civilization itself. And at about this point Murnau begins to put more emphasis on the animal-like Renfield, who was present in the midst of society from the start, an extension of his “Master.” We see the impotence of society to combat the forces that have been released, in the scenes of the hysterical pursuit of Renfield, where the baffled pursuers vent their fury on a scarecrow.

Nosferatu’s real opponent is not Jonathan but Nina. The film endows her, as it does the vampire, with a superhuman force. Just as Nosferatu telepathically controls Renfield at long distance, so Nina is able telepathically to save Jonathan, at the moment when the vampire may destroy him. In the last scenes of the film the sexual overtones inherent in the vampire myth (and exploited throughout the recent British Dracula cycle) become explicit. The window from which Nosferatu watches, like a sinister reflection in a mirror, is opposite the couple’s bedroom. It is Nina the vampire wants, from the moment he sees her miniature; and the intercutting of Jonathan’s and Nosferatu’s journeys—intercut also (as we have seen) with Nina’s ambiguous expectations—suggests that the struggle is essentially for her. Nina embodies the film’s most apparent positive values, the civilized human existence for which animal nature, in the form of Nosferatu, has been repressed. Her sacrifice of herself is ambiguously motivated. From her window she watches the procession of coffins down the street, and gives herself to remove the plague from the world. But the film also makes clear that she is giving herself to save Jonathan: a t her moment of decision, she is stitching a sampler that says, “Ich liebe Dich.” Her sacrifice thus carries Christian overtones more complex and powerful than the hold-up-the-cross-and-splash-him-with-holy-water tactics of most vampire films.

But one must beware of emphasizing this at the expense of the sexual meaning of the last scenes. One is tempted toward a straight psychoanalytical interpretation: Nosferatu is the symbol of neurosis resulting from repressed sexuality (repressed nature); when the neurosis is revealed to the light of day it is exorcised, but the process of its emergence and recognition has been so terrible that positive life (Nina) is destroyed with it. The real energies displayed in the film belong to the vampire. Or another way of looking at it: if one accepts my implication that Jonathan and Nosferatu are really the same character, then Nina must accept in her husband what he himself can’t confront or control. At the same time, there is in the images and the acting a suggestion that Nina secretly and ashamedly desires the vampire. It is worth repeating at this point that the film, in the form of myth rather than psychological drama, is by no means restricted to a single allegorical interpretation. Evil (if one can call Nosferatu simply evil) is destroyed; but good is destroyed with it. The ultimate effect, for all the uplift of the final shot of the vampire’s shattered castle in the sunlight, is of a tragic pessimism.

Yet this is still to make the ending too simple. I haven’t taken into account the very striking change in Murnau’s presentation of the vampire in the closing sequences. After building up his monster into a figure of terrible power, Murnau finally presents him as essentially pathetic, helpless, a victim. When he at last appears in the position of a reflection, at the opposite window, he seems suddenly a pitiful old man at Nina’s mercy. The image arouses powerfully ambivalent feelings toward the repressed animal nature Nosferatu represents, and the film’s most disturbing final effect arises from this. Our sense that the greatest energies in the film are Nosferatu’s intensifies the poignance of his helplessness and his destruction; and we cannot entirely evade the feeling that Nosferatu is, in a way, an important part of ourselves. Our attitude to Nina, to Christian sacrifice, to the centuries of “Christian” repression that have made such sacrifice necessary, undergoes subtle modification.

I threw out earlier a comparison with D.H. Lawrence’s “Snake.” Both the parallel and the difference are very striking. In Lawrence’s poem the snake, like Nosferatu, comes out of a dark hole to become a symbol of all that civilized society disowns and rejects; and the poet, driven by what he calls the “voice of his education,” drives it back into the subterranean darkness by casting a log at it. But to Lawrence the snake, though venomous, is essentially beautiful and pure; he calls it a “god,” a “king uncrowned in the underworld, now due to be crowned again,” “one of the lords of life”; he is ashamed of the “pettiness” provoked by his “accursed human education,” a pettiness he feels he must now “expiate.” If one must simply choose, it is perhaps more realistic to see all that civilization has repressed through the centuries emerging as a Nosferatu rather than Lawrence’s pure and uncorrupted snake. But few will deny, I hope, that Lawrence’s image and the vital positive faith it exemplifies have their validity too—are given it, indeed, by the convincing presence in Lawrence’s own work of just those energies the snake symbolizes. To depict our repressed animal natures, our sensuality, solely as a Nosferatu, while opposing to him the somewhat bloodless Nina, cannot but strike us as unhealthy.

The unhealthiness is not only Murnau’s; it derives in large measure from the film’s background in German Expressionism. If one takes THE CABINET OF DOCTOR CALIGARI as the Expressionist film par excellence, then one will see that even as early as NOSFERATU the Expressionist tendencies were already becoming modified and muted in Murnau’s work. The chief distinguishing feature of Expressionist style (from which its name derives) is the deformation or distortion of reality for the sake of direct expressive effect. Little in NOSFERATU corresponds precisely to such a description; there is nothing in it like the fantastic, twisted, hallucinatory décors of CALIGARI. On the contrary, one is continually struck by the context of reality given to the horror-fantasy by the use of real locations (doubtless, as Raymond Durgnat has suggested, one of the things that so attracts Georges Franju to Murnau’s film): the wild mountains, the forests, the sea; even the city scenes were largely shot in the streets of Hamburg. Normally, one would stress the film’s surprising freedom from Expressionist mannerisms. Nevertheless, Expressionist influence pervades the film. The first shot of the vampire’s castle jutting up from the rock, the strange geometrical patterning of arch-forms out of which Nosferatu emerges to meet Jonathan, the use of “unnatural” camera angles as in the shot from the hold of the ship, the trick effects, the huge shadow as Nosferatu ascends the stairs to Nina’s room, the shadow of his fingers clenching into a fist upon her heart—these are only the more obvious manifestations of the Expressionist manner.

But Expressionism in the German cinema was more than a style; it was an atmosphere and an ethos. Among its salient characteristics were an oppressive sense of doom or fate, and an obsessive association of sensuality with evil. By identifying its “Doom” figure with repressed sensuality NOSFERATU makes perfect sense of the co-existence of these characteristics; if it is partly limited by the movement that produced it, it can also be seen as the fulfillment of that movement. And for the film to make sense it is obvious that Nina must be what she is: pallid, emaciated, seeming drained of blood even from the outset, her face at times almost a death’s head, in the last scenes agonized and exalted like Christ on the cross. She is the inevitable corollary of the repressed Nosferatu.

Such tendencies are still present in SUNRISE, again associated with the stylistic characteristics of Expressionism: the hero’s wife strikes one as quite sexless, while sensuality (in the person of the Woman from the City) is willfully destructive and evil. Only in TABU—under the complex influences of America, Robert Flaherty, and the Pacific Islands—was Murnau able to achieve a healthier, more positive and integrated attitude toward the body. Significantly, only fleeting traces of Expressionist style remain in that film; and I doubt if one would call them that if one were not alerted by knowledge of Murnau’s background.

The complexity of film as a medium is suggested by the multiplicity of its affinities with the other arts. It is like drama in that it is centered on actors; it is like the novel in that it has the novelist’s narrative freedom, unrestricted to a specific stage set or acting area; it is like poetry in the way it can be organized in terms of developing themes or imagery; it is like painting in that it is a visual art in which composition, the placing of characters in a décor, the catching and framing of a particular pose or gesture can play a a-udal role; it is like music in that, unlike a painting, it has existence in time as well as in space, a fixed duration within which, acting directly on the recipients senses, it involves his consciousness and his emotions in a continuous flow of forward movement.

One can define certain directors to some limited extent through the particular affinities of their art to other arts. Renoir, for instance, for all his roots in the world of French Impressionism and his own father, for all the recurrent fascination with the theater, is, in the works one feels to be most fully representative, essentially a musical director; movement, flow, counterpoint, development, variation, are terms that repeatedly present themselves when one is discussing THE RULES OF THE GAME or THE GOLDEN COACH. Murnau’s affinities are with music, painting, and poetry.

His art is, of all great directors’, furthest removed from the novelist’s. One is struck by the simplicity of Mumau’s subjects—or, if simplicity seems a dangerous word, by their traditional, basic, mythic nature: vampire mythology, the Faust legend, the “Song of Two Humans” (SUNRISE’S subtitle), the struggle for individual rights against tribal (social) decree in TABU. The psychological interest of his films is general rather than particular. He shows remarkably little of the novelist’s interest in the development and interaction of individualized characters. His characters are certainly not shallow—they are capable of the most intense and ultimate emotional commitments—but their depth is that of universal archetypes rather than of detailed individual studies. We never even learn the names of the characters in SUNRISE: they remain to the end simply The Man, The Wife, The Woman from the City. NOSFERATU, SUNRISE, and TABU all tend toward the of myth, or archetypal pattern. We have not all tried to murder our wives; but the whole pattern of estrangement, crisis, and reconciliation we follow in the half of SUNRISE is one that strikes an immediate sympathetic response in most of us. It seems so satisfyingly representative as to be accepted as an archetype of how a marriage relationship is resolved.

The affinities of Murnau’s art with painting (he studied both art and music at university, and was a painter, art historian, and “artistic designer” before becoming a director) relate inevitably to his Expressionist background. Surprisingly, the Expressionist influence manifests itself more obviously (if less pervasively) in SUNRISE, made in Hollywood when German Expressionism as such had almost played itself out, than in NOSFERATU, made in Germany at the height of the Expressionist movement. But by the time Murnau reached Hollywood his reputation was based not only on the celebrated camera movements of THE LAST LAUGH but on the elaborate (and often remarkable) trick effects of FAUST.

This doubtless partly accounts for the most obviously Expressionist aspect of SUNRISE: that use of superimposition and stylized sets that once appeared the film’s supreme distinction (one still finds it singled out in reference books) and now seems its least interesting feature, at times more disruptive than expressive. Cinematic tricks seldom wear well after repeated viewings, simply because an expression, a gesture, an exchanged glance, can communicate far greater complexity than the most elaborate barrage of effects—can continue to convey fresh nuances and new meanings long after we have exhausted the sense of a metaphorical superimposition. In FAUST the tricks are associated with Mephistopheles’ supernatural powers, and hence are quite appropriate; in SUNRISE their obtrusive technical sophistication seems slightly at odds with the simplicity of the subject matter. There is all the difference in the world between the elaborate technical display of the superimpositions and the perfectly functional and expressive technique of the trolley-ride sequence, for instance.

Apart from the opening holiday-and-travel collage, the superimpositions are used to present subjective states of mind or imaginings of the Man (in the first part of the film) and of the united couple (in later scenes). The vision of the city evoked for the man by the City Woman is an extraordinary achievement in its elaborate sets and superimpositions combined with lateral tracking shots. The shot suggesting the City Woman’s possession of the man and his inability to struggle against it is remarkable in its timing of gesture in relation to superimposed image. We see the man sitting on his bed; a superimposition of the woman appears behind him with her arm around his neck. He turns his head aside as if to reject her, and the image dissolves, to be replaced, almost at once, hydra-like, by three superimpositions that come virtually to fill the screen. She is in his arms looking up at him, she is behind him, and a huge though very indistinct image of her face becomes visible in the background, so that we see her in, respectively, right profile, left profile, and full face. The hunched body and tormented face of the man become the center of a complex composition that powerfully expresses the woman’s dominion over him.

One or two other examples could be considered rather tasteless in their pseudo-naiveté: the field of flowers the couple imagine themselves walking through after their symbolic remarriage (to which we dissolve from the clumsily back-projected city street, the one moment in the film where a process shot actually jars, as the film’s fantasy-level awkwardly intrudes into its reality-level); the floating, circling cupids seen when the couple are under the influence of wine. To defend these as the sorts of images a simple peasant might conjure up strikes me as merely patronizing, and the effects achieved are too false-naïve to work on a deeper level.

SUNRISE

If SUNRISE is, through its knotting together of affinities with other art forms, the most synthetic of all films, the synthesis can also be described in terms more specifically cinematic: the marriage of Méliés and Lumiére. One can establish within the film the opposite poles of the cinema’s aesthetic beginnings: the vision of the city conjured up by the City Woman out of the marshes, a moment of pure Méliés magic, totally fabricated; the shot, crucial to the film’s development, showing the couple’s emergence from the church, “remarried,” where the camera is placed, completely static, before a simply staged action it is then allowed simply to record. Interestingly, the two moments are not only stylistic but thematic opposites, marking respectively the eruption of untrammeled libido and its subjugation through the order of marriage. But elsewhere in the film Méliés artifice and Lumiére simplicity unite.

In likening Murnau’s art to the painter’s it was not only the superimpositions I was thinking of; the Expressionist influence pervades the style of the movie in subtler forms. Filtered through Murnau’s sensibility, Expressionism becomes less a matter of the distortion of reality than of selection and emphasis, a process admirably suited to the concern of myth with essentials. Several shots in the film immediately suggest paintings, most obviously the “still life” of wooden bowls and bread on the table that epitomizes for us the simplicity, totally devoid of luxury yet sturdy and sustaining, of the couple’s domestic life, in contrast to the exotic allurements of the City Woman (who is at the moment at the gate, whistling for the man); the second-honeymoon image of the boat sailing home by moonlight, a composition—black background, white sail, path of moonlight on the water—that evokes the simplified color blocks (though not the clamorous colors) of the Brucke group out of which Expressionism developed; and the unforgettably beautiful shots of boats and lanterns moving across the dark water, as the man and the search for the wife after the storm, which in the use of patterns of light and reflected light suggests an Impressionism offset by the intense emotional-dramatic content of the scene.

Again and again in the film, especially in the performances of the two principals (George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor), one notes how a particularly expressive gesture, pose, or bodily movement is caught, emphasized, and framed very much as a painter would seek to capture it on canvas: the wife standing beside the table with the bowl of soup, after her husband has stolen out to join the woman; the baby touching the wife’s tightly knotted hair as she weeps into the pillow; the wife in the early morning leaning solicitously over her husband as he lies asleep, fully dressed, on the bed.

Most striking of all is the scene in the boat—the attempted murder. One’s first mental images in recalling the scene will probably be of two posed, almost static figures: the slender and fragile wife, filmed from a high angle that intensifies our sense of her smallness and vulnerability, cowering back until one fears she will topple backwards from the boat, holding out her clasped hands to pray for mercy, leaving her precariously bent-back body wholly without support; and, in direct opposition, the low-angle shots of the husband that emphasize his bulk, his hunched yet looming form, the terrible rigidity of a body forced by the will into an action felt as monstrous by the man himself, in some deep emotional center beneath the sensibility he has deliberately numbed. For the sequences culminating in the attempted murder, Murnau had George O’Brien’s shoes weighted with twenty pounds of lead, a device essentially Expressionist in inspiration. It confers on the character that quality of being at once oppressor and victim. The shambling heaviness of his movements makes him appear a monster (almost in the literal, horror-film sense), yet also suggests the unnatural effort of will by which he is suppressing his own finer feelings.

But any sense we may have of Murnau as a dramatic portrait-painter is very quickly qualified by our sense of movement in his films. It is this that suggests affinities music (affinities Murnau himself acknowledges in the subtitles of certain of his films, so that NOSFERATU is “Eine Symphonie des Grauens” and SUNRISE “A Song of Two Humans”). If our first mental images of the scene of the attempted murder are of static portraits, these almost immediately place themselves in a context of significant movement. Even the posed attitude of the cowering wife is counterpointed by the background of shimmering, sunlit water. The static moment of confrontation in the boat, given such intensity by the portrait-like poses, becomes the still point of decision in a progress clearly more than physical: the deliberate, inexorable movement of the boat from the shore (interrupted by the incident of the dogs attempt to follow) as the man rows his wife out to murder her; the frantic, panic-stricken struggle to row to shore, after he has relinquished the attempt but revealed the intention, the intense drive expressed in the repeated shots of the prow cleaving the water; his pursuit of her as she flees in terror across meadow and rocks to the tramlines; the celebrated tram-journey itself.

This feeling for the expressive force of movement is perhaps the essence of Murnau’s art. It was already powerfully present in NOSFERATU, most notably in the intercut journeys by land and sea (which startlingly anticipate, and excel in emotional intensity and suggestive significance, Hitchcock’s intercutting of actions in the build-up to the climax of STRANGERS ON A TRAIN), but also in the overall effect of the film as a dynamic progress from the flowers-and-kitten scene of the opening to Nina’s death at the end. Physical movement in Murnau’s films is seldom merely incidental, or merely functional to the plot.

It is the surface manifestation of all that is going on beneath the surface: the dynamic drives of soul and psyche. The quality I am indicating can be clearly defined by contrasting with it the essentially static effect of the fun-fair sequences of SUNRISE, where there is a continual bustle of incidental movement—milling crowds, the panic surrounding the escaped pig, the dancing—but little sense of progress. To develop my musical analogy, one might say that in the outer movements of SUNRISE there is continual modulation, whereas one feels the fun-fair sequence, for all its rapid motion, to be rooted in one key.

With this dynamic movement goes a feeling for space and distance that no director has surpassed. Counterpointing the forward impulse is the use of enclosure (cottage, boat, tram, café) an oppressive feeling of separateness within narrowly circumscribed bounds. Throughout these scenes husband and wife scarcely touch each other. The distance between them in the boat—physically so small, spiritually so vast, with the husband doggedly willing himself on, refusing to see his wife—becomes the decisive factor in the scene’s visual effect. When he stands to kill her, and is forced to move toward her and look at her, the low placing of the camera gives great emphasis to his hands; his sudden gesture of desperately hiding his face in his forearms, as the full enormity of what he is doing breaks upon him, has maximum visual force. We also become very aware of his wedding ring (whereas the wife’s is seldom visible; we are only made conscious of its existence once, I think, when the man who makes advances to her in the barber’s shop glances down at her hands, partly hidden by the flowers she is holding, to see if she is wearing one). Afterwards, he can’t touch his wife with the hands that were going to kill her.

She rushes past him to escape from the boat, and later to flee from the tram, and he is powerless to use his hands to stop her. Only when he saves her life—snatching her back from in front of a car as she dashes across the city street—can he put his hands on her again.

In the trolley, there’s the same sense of separateness-within-enclosure as in the boat, but intensified by the couple’s extreme physical proximity. The roles are now reversed: it is the husband who pleads silently for contact, the wife who holds herself back. The tightness of the compositions, man bowed, wife cringing, imprisoned within the enclosing structure of the tram, makes their inability to touch appear unbearable.

The uses to which Murnau puts open space are even more remarkable. The supreme achievement is perhaps the ending of TABU, but I shall cite two examples from SUNRISE, one where Murnau deliberately undermines our sense of spatial relationships, one whose effect depends on our precise sense of real distance, a Méliés shot and a Lumiére shot. The extraordinary tracking shot that accompanies the man’s walk out to the marshes to meet the City Woman is a classic instance of the use of technique for expressive purposes. At the beginning of the shot the man is about to cross a small bridge with a wooden handrail; the camera is behind him, ahead all is misty and dark, and the moon is at the top left of the image. The camera follows the man across the bridge and the moon disappears from the frame; with it goes our ability to keep our bearings with any certainty. The camera follows the man’s complicated movements as he passes by an intervening tree and climbs over a fence; then he leaves the frame, left, and the camera moves on forward toward some foliage.

Up to this point, although the shot is never strictly subjective the movement of the camera has been closely associated with the windings and turnings of the man, and we tend to assume that it is now preceding him through the bushes, as the foliage parts to reveal the City Woman. Behind her, rather disturbingly, is the moon; we can’t doubt the evidence of our eyes, but we have a vague sense that it should be further to the left, outside the frame. We also expect the man to emerge at once from approximately where the camera emerged; however, after a lapse of time sufficient to enable her to check her appearance briefly, the Woman turns to welcome him left of frame, and he at last reappears from that direction.

In fact, the evidence of our eyes is false, our sense of direction less at fault than we have been deceived into believing. According to Lotte Eisner, Murnau had two artificial moons constructed in the studio for this one shot. We are not of course conscious of any such device while experiencing the scene, but everything in the shot is devoted to subtly undermining our spatial certainties. Its effect is a perfect balancing of objective and subjective. Through the camera-eye we watch the man until he leaves the frame and when he reappears, and when we think the shot has become subjective we are proved mistaken, which has an immediately detaching effect. On the other hand, our increasing physical disorientation during the shot communicates very directly the spiritual disorientation of the man; like us, he has lost his sense of direction. Significantly, the shot moves us, with him, further and further into the marshes. There is a danger, in analyzing the mechanism behind the shot in such detail, of making it sound theoretical, but one certainly doesn’t feel this while watching the film. It is a perfect example of direct emotional communication.

Murnau is rightly sparing of such effects; indeed, I know of no other in his work that closely parallels this. It is felt (albeit subconsciously) the more strongly because of his habitual fidelity to the realities of space. The rewards of that fidelity can be illustrated with the incident involving the dog. The man is taking his unsuspecting wife out on to the lake to drown her; she thinks she is going for an outing. As the man prepares for the “accident,” stowing the bundle of rushes out of sight in the boat, the dog, tied to its kennel outside the cottage, barks excitedly. The man, hearing, responds with obvious guilt, which we see him suppress, just as he started guiltily when the horse “caught” him hiding the rushes in the stable the night before: to him, it is as if the “natural” animals are rebuking him for his unnatural course of action. The dog becomes associated in our minds with nature, and with domesticity, the security of the home. Emotionally, we register it as a possible means of safety for the wife, however irrational this may seem; its barking seems an attempt to protect or warn her.

The sequence is notable for its beautifully controlled movement of emotional tension, resolution, and reversal. The wife pats the dog, to calm it and to say goodbye. It is held to the kennel by a leash—first obstacle. She goes out through the cottage gate, and shuts it carefully behind her—second obstacle. She comes down the path, into the boat, the man pushes off—and the ever-increasing expanse of water becomes the third obstacle between the wife and possible rescue. Then, in a series of shots carrying an exhilarating feeling of release, we see all the obstacles cleared: (1) the dog breaks its leash; (2) the dog clears the gate; (3) the dog rushes down to the end of the jetty, springs into the water and swims energetically toward the boat. The climax of the “release” effect depends for its full effect on Murnau’s preservation of physical space within the frame. Instead of cutting to a close-up of the dogs leap (the obvious way to get impact), he shoots the final stage of the dog’s pursuit in a single take, from the boat, so that the moving boat and the jetty are both in the image, with the dog struggling through the intervening, and widening, stretch of water.

I have so far discussed Murnau’s art in SUNRISE in relation to its affinities with painting and music, and the tension between these affinities. The film can also be seen as a visual poem composed of densely interrelated motifs in which (in certain sequences) every image has meaning—or, if that suggests something too precise and susceptible of neat explanation, then evocative power—by virtue of its interaction in our minds with those surrounding it.

Consider the sequence of the man’s return at night with the rushes, after his rendezvous in the marshes with the City Woman. We see him approach the cottage against a background of fishing nets hung up to dry. The camera pans with him as he moves to the gate, his footsteps heavy and dogged. The next shot shows the wife asleep in bed, a cross formed across the bed-cover by the pattern of light and shadow cast by the window—an ambiguous image, suggesting at once a protective Christianity and a corpse laid out on its bier. Cut back to the man outside the cottage; tree shadows are cast on the wall by the moonlight, recalling the nets of the previous image, continuing the feeling of his being trapped. He stealthily enters the barn. There follows the shot in which, just as he is about to hide the rushes, the head of a horse enters the frame from the left and the man starts guiltily. He then covers the rushes with a sack, his movement going from right to left of the screen. He enters the bedroom; and again one notices the pattern of crosses (the window itself and the shadow it casts).

Emotionally, the effect of these shots arises from the juxtaposition of different, even contradictory ideas in our minds: the planned murder; the wife as a corpse; the as mysteriously protected; the sense of the husband as trapped and doomed. He solve to an image of water makes it appear as if he, not the wife, is drowning. The dissolve completed, the camera tilts up from the lake to show the in the early morning sun and mist. Then we see the wife, dressed, leaning over her sleeping husband. She strokes his hair and covers him with a blanket; the movement is from left to right of the image, like a mirror-inversion of the shot of the husband covering the rushes. The wife leaves, the man wakes up and starts. Murnau cuts abruptly to an apparent subjective shot of the rushes uncovered, a hallucination that expresses graphically the man’s guilt, his terror of revelation. But he is in fact looking toward his wife’s bed.

The sequence works not in terms of a Meaning one could neatly verbalize, but in terms of the resonances set up by the juxtaposition of the shots, with their echoing of ideas and images: the drowning of the wife and the “drowning” of the husband, the furtive covering of the rushes and the answering image of the wife tenderly covering the husband, the revealed rushes where the empty bed should be. The communication is again emotional rather than intellectual, the connections felt rather than consciously analyzed, as one feels the interlocking images of a poem or the varied but related phrases of a piece of music. Later, when the man goes to fetch the rushes from the shed, there is a closeup of his hands tightly encircling them in a strangling gesture. He is about to drown his wife, but earlier it was the City Woman we saw him attempt to strangle, as he will again near the end of the film. The image powerfully communicates the ambivalence of the man’s feelings.

This concentrated richness of effect never impedes the flow of the film. It is always subservient to the inner drive from the broken relationship of the opening to the couple’s second “wedding,” which the spectator experiences as a single continuous movement. Crucial to that movement (because this is the moment where it most clearly surfaces, manifesting itself visually) is the famous trolley-ride. “Famous” because so often referred to—though critics seem strangely reluctant to fry to say how it works, and why it is so moving. Jean Domarchi, in his pamphlet on Murnau, is fairly typical: “There is a sort of incantatory magic, a sort of visual alchemy, whose se is very difficult to penetrate”; and he leaves it at that. “Visual alchemy” is quite felicitous to describe the seemingly effortless flow of movement that carries us past lake, through trees, past a cyclist on a road, through factory yards into the city street—as if the scenery (composed of commonplace-enough objects) were a shifting dream-landscape—but it doesn’t take us very far.

Extract the sequence and show it to people who haven’t seen the whole film, and they won’t, I think, find it particularly historical terms. The emotional effect depends essentially on context rather than technique. Building up to it is the cumulative movement of the marriage relationship so far, particularly the wife’s realization of what the husband was going to do, and the man’s answering realization of the enormity of the attempted murder. When he puts his hands to his face in the boat, both to blot out the sight of her cowering away from him and to hide his own deep shame, it is as if he is released from a spell. The intensity of these reactions reveals how deeply the couple love each other; the vague and conventional phrase “the sanctity of marriage” is suddenly felt as a human reality, through our horror at the man’s brutal violation of it.

The first appearance of the trolley car—another good example of Murnau’s fidelity to the concrete reality of space—has about it something of the miraculous. The wife is fleeing in terror up an incline, over rough, rocky ground and through trees; there is no sign of human habitation. Then the camera swings in an easy, natural pan to reveal the tracks, and at that very moment the trolley comes into view round a bend. The pan simply connects the terrified running woman with the smoothly gliding trolley, whose appearance is the more surprising in that it is presented so unemphatically.

It is impossible to label the trolley with any of the usual aesthetic terms. It isn’t “symbolic” (symbolic of what?), neither is it “naturalistic” (its appearance is too arbitrary, too neatly coincidental); and I don’t think we are asked to see it as an act of God. If one feels it, nonetheless, to have a perfect appropriateness at this precise point in the film’s development, this is intimately bound up with the way it takes up and extends the movement, in both the literal and metaphorical senses. It is in the car that the tension between stillness and motion, painting and music, reaches its peak—the feeling of forward movement counterpointing the static, quasi-paralyzed attitudes of the man and the wife. Enclosed in the very confined space within the car, forced into dose physical proximity yet unable to touch each other, they appear locked in indissoluble states which the progress of the trolley subtly denies, becoming expressive of the interior progress of their souls, of which they are unaware. Up to this point in the film Murnau has consistently emphasized effortful movement (the doomed tread of the man into the marshes, his dogged, lead-weighted walk to the boat, his slow but inexorable rousing of the boat to deep water, the frantic struggle to shore, the hysterical flight and pursuit over rocky ground). On the trolley-car, movement becomes effortless and dreamlike, the couple are in a state of suspension. All action hitherto has depended on the man’s perverse and possessed will; now at last the will is in abeyance, and things just happen as part of a natural forward flow.

Other factors contribute to the scene’s emotional effect. One is our awareness of the ironies inherent in this journey to the city. It was the man’s desire to accompany the City Woman when she returned to the city that drove him to accept the plan to murder his wife; now it is the wife with whom he makes the journey, all the circumstances changed. Further, we earlier watched the wife’s excited preparations for the pleasure trip: the pleasure deriving from her hope of reunion with her obsessed husband rather than from the incidental delights of the trip itself. During the trolley ride we compare the reality of her outing with her expectations of it, her present misery with her past joy—but already with a presentiment (conveyed by our sense of forward movement) of a deeper joy to grow out of the misery. Finally, there is the intrusion of a prosaic external reality into the private situation: a recurring motif in this part of the film, which usually takes the form of the man’s having to fork out money (on the tram, in the café, to the flower seller). I am reminded of Auden’s point about the Old Masters in “Musée des Beaux Arts”:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.

Similarly, on the trolley car, the couple’s immersion in emotional experiences of the utmost depth and intensity is interrupted by the commonplace business of paying fares. The effect of this is two-fold: it op poses the ultimate experiences of the couple to the workaday world about them, continuing in indifference; it also reminds us that they are part of that world, and brings home to us the normality of the experience they are undergoing, of a sort which every human being will comprehend, conceivable within any marriage.

The goal of this whole great first movement of SUNRISE is the wedding scene, culminating in the sublime simplicity of the moment when the couple emerge from the church and the people awaiting the bride and groom line up for them, as if in acknowledgment of their “marriage” moment expressed in a single static longshot, totally devoid of technical display. In my experience of the anema certain moments continue to stand out over the years as touching particularly deep responsive chords: Dean Martin pouring back the whiskey in RIO BRAVO (“Didn’t spill a drop”); Ingrid Bergman in Rossellini’s JOURNEY INTO ITALY discovering, that “Life is so short,” after her experience of the Pompeii relics; Satyajit Ray’s Charulata calling for the lamp that will illumine her tentative, suspended reconciliation with her husband on the threshold; Louis Jourdan at last remembering Joan Fontaine as she was the very first time he saw her, at the end of LETTER FROM AN UNKNOWN WOMAN. On reflection, these apparently heterogeneous moments all reveal something in common: they are moments where an essential human destiny is decided, and they are moments (if in some cases somewhat equivocally) of triumph, the triumph growing out of a profound self-confrontation. The exit from the church in SUNRISE is such a moment: in its affirmation, the least equivocal of all. One feels that this is the couple’s real marriage: the accumulated emotional force of all that has led up to it has made the concept of marriage as an ultimate union a human reality both to the characters and the spectator.

SUNRISE is less a “Song” than a symphony in four movements: the long, emotionally exhausting first movement, with its extraordinarily concentrated development and irresistible, if leisurely, forward drive; an andante amoræo (the barber shop and photographer scenes); the funfair scherzo; and the intense and emotionally demanding finale of journey home, storm, death, and resurrection. If the main weight of significance is in the first movement, this is also a characteristic of the classical symphony, and not to be taken as evidence that what follows is unworthy. The primary function of the scherzo is to set off the intensity of the film’s outer movements with its relaxed, comparatively trivial gaiety, and to allow us to recoup our emotional energy; it is relaxed not only in mood but in organization. The finale achieves overwhelming power and beauty, but its emotional effect is intrinsically less complex than that of the first movement: the threat is no longer internal, the conflict is the simpler one of human life against the elements, and against the unpredictability of nature and chance.

If one does not feel prompted to analyze the fun fair scenes in as much detail as the first section of the film, this is again in the nature of the scherzo. They are led into by means of the relatively short, transitional andante: the sequences after the wedding, comprising the visit to the hairdresser’s and the visit to the photographers. They at once complete the progress of the first part and introduce the essential motifs of the scherzo. The scene in the hairdresser’s becomes a quasi-ritualistic enactment of the man’s role as husband; under the watchful eye of his wife he resists the advances of the manicurist (who physically resembles the City Woman), and protects the wife from the advances of her would-be seducer. The scene in the photographers completes the ritual of marriage with a wedding photo. At the same time we become aware of the two main themes of the funfair episode: the couple’s ignorance of city ways and city culture (the incident of the headless statuette); the trivializing artificiality of human relationships within that culture (the manicurist and the seducer). The funfair sequence itself is framed symmetrically within shots of the entrance to the pleasure palace.

It is rumored that Murnau was “encouraged” by the studio to introduce more comic business than he had originally intended; and it must be admitted that certain of the incidents (the drunken waiter and drunken pig, the slipping dress-strap) are only loosely related to the thematic development and remain somewhat extraneous in effect, partly because the film has involved us so intimately in the couple’s experiences and both these incidents happen beyond their consciousness. Our primary impression is of the couple’s simple happiness, but this is continually disturbed by a sense that they are being distracted, at such a key moment in their lives, by the inessential.

Significantly, immediately before the fun fair scenes we are reminded of the continuing presence, back in the village, of the City Woman, whom we (like the man) have completely forgotten; we see her ringing in pencil an advertisement in a newspaper exhorting farmers to sell their farms and move to the city. Our impression of relaxed gaiety is clouded by an uneasy feeling that the man has forgotten the past too easily, and forgiven himself too lightly. In the city the couple are surrounded by people preoccupied with the trivial (such as falling dress-straps); and, if they are not exactly harmed by this, they are not untouched by it. The fun of throwing balls to make piglets roll down a chute temporarily distracts the man from his wife at a time when we want the couple to be completely united in their enjoyments.

We may reflect that on one level at least the man’s obsession with the City Woman was itself a preoccupation with inessentials. He seemed scarcely aware of her as a human individual (and she only becomes this momentarily for the spectator, in her defeat at the end of the film); he saw the supposed glamour and exoticism of the city personified in her. Murnau’s attitude seems not unlike Wordsworth’s to the St. Bartholomew’s Fair, which “lays/The whole creative powers of man asleep.” The city that was a mesmerizing vision in the man’s mind proves in reality trivial and slightly ridiculous. Yet the attitude is not puritanical or purist, the meaning of these central scenes not simple: the couple has fun, and there is no sense that Murnau means us to condemn them for it. Also, they are never really contaminated, because they remain essentially outside (expressed most strikingly in the peasant dance). The man had aimed to become integrated in the city (with the City Woman); instead, everything that happens emphasizes the foreigners of the city to the couple. We feel now that the marriage is secure from internal disruption; there is still some doubt as to whether the couple adequately grasp its supreme value. The man is distracted by the pig-slide, the wife is lured by the glamour of the ball-room; they have yet to acknowledge that the reality of their union puts such diversions in their proper perspective. Sure of each other, they have yet to feel their private world in the context of an unpredictable, uncontrollable, and often terrible external universe.

The rumor that Murnau was encouraged to embellish the middle section of SUNRISE with extraneous comedy also has it that he was persuaded toward the film’s optimistic ending. On the purely internal evidence of the film itself, it is easier to believe the first part of the rumor than the second. We do, while watching the film, feel at moments in the middle that it has lost its sense of direction. The essential movement seems completed with the couple’s symbolic remarriage, and, as incident follows incident, we find ourselves asking where precisely it is all going. This very lack of a strong sense of purpose takes on expressive quality in the context of the whole: the electrifying moments when the storm strikes suddenly place the whole intervening scherzo in perspective, and the film, having lulled us (as well as the couple) into a false sense of security, rouses us from it with shocking abruptness.

But, if one has passing doubts about the proliferation of comic detail in the middle of the film, no one (I take it) even temporarily doubts the rightness of the ending, the affirmation it expresses seeming so perfectly justified by the cumulative force of all that has gone before. If we look outside the film, however, it is easy to see that the originally planned tragic ending, with its poignant irony (the husband drowning after saving his wife with the rushes that were to save him after he had drowned her), is much more in keeping with the tragic vision of other Murnau films. NOSFERATU and TABU, like SUNRISE, celebrate the supreme value of love between man and woman; but, unlike SUNRISE as we have it, they affirm it tragically, through death or loss. Even FAUST, with its final magnificently asserted redemption through union, expresses this through the couple’s earthly death.

The structuralist school will doubtless tell us that SUNRISE ought to have ended tragically, and will consider this proven, not by the rumor, but by what we know of Murnau’s total oeuvre. In view of the irresistible emotional convincingness of the ending as it stands, I would guess that, if Murnau had to be “persuaded,” the pressure needed was not great; and that, once he had capitulated, he had no difficulty in committing himself wholeheartedly to the unequivocally optimistic ending we now have. The main point—the affirmation of the ultimate value of marriage—is, after all, common to both versions. Nor did the irony have to be entirely sacrificed. It is there, beautifully, in the rushes, with their accumulated overtones from the first part of the film and their association with nature. A key factor in the plan to murder the wife, they become the husband’s means of saving her, a touching and concrete expression of the idea of salvation developing out of evil.

It is in the last part of SUNRISE that the elemental light-and-darkness symbolism, to which the title itself directs our attention, rises to full explicitness. We are reminded that NOSFERATU, also, ended with the powers of darkness defeated by the sunrise, and the parallel may alert us to look for further resemblances that are not obvious at first sight. The City Woman, like Nosferatu, is a creature of the night; and like the vampire we see her by daylight only once, at the end, as she is driven away from the village in a cart, vanquished. In the daylight, she appears suddenly fragile and human, just a girl; all her power and dominance have left her. As a nocturnal creature, she is associated visually with the full moon, suggestive of witchcraft, and there is a strong suggestion of the witch-enchantress in Murnau’s presentation of her, in the way in which she possesses the man’s soul. But she is also like a cat, or some night animal. We feel this, I think, from the start, because of her slinky movements, her sleek dark hair and clothes, and the way she lures the man from the cottage by whistling for him, an animal-like summons. These suggestions are confirmed in the last part, when, as the distraught husband leads the search for his wife and the boats set out, Murnau has the City Woman watch the scene secretly, along the branch of a free bent over the pathway.

The association of darkness, animal nature, and sensuality links the City Woman irrefutably to Nosferatu, and, indeed, one finds in SUNRISE once again the sense of a dichotomy in nature one found in the earlier work: the surface world of flowers, horses, digs, sunlit meadows, sunlight on water; the hidden underworld of precariously repressed forces, the half-animal vampire, the cat-like woman. For there is a curious unresolved split in the meaning of SUNRISE that has nothing to do with superfluous comedy or imposed happy endings. On one level the temptress is associated with the city, its false glamour and superficiality, its trivializing of relationships; this is apparent from her preoccupation with a seductive façade, notably in the scene where she compels her aged landlady to interrupt a meal to polish her shoes. But Murnau’s images, and the association he builds up around the character, confer upon her far greater potency than such a description can account for.

This is why some people find the film overburdened, weighted with heavier significance than its simple fable-like narrative can sustain. The potent suggestiveness of the scene in the marshes, and the terrible and somber power of the sequences leading up to the attempted murder, evoke a response much deeper and more disturbing, and more deeply rooted in universal experience, than can be accounted for in terms of a banal story about a simple farmer and a city vamp. The scene in the marshes evokes a and primitive sensuality quite at odds with the trivia of city life evoked in the scherzo.

The visionary city the woman conjures up, as if by sorcery, out of the marshes and the night, only superficially resembles (in, precisely, its glittering surface) the “real” city subsequently visited by the couple. The visionary city is a manifestation of unrestrained libido. The first thing we see is a city square whose centerpiece is, unmistakably, a huge erect phallus; after the ensuing chaos of movement and dazzle (the combination of rapid camera movement and montage producing an effect of bewilderment and frenzy), the energetic heaving of the jazz band is overtly sexual in connotation, very different from the romantic but contained ballroom dancing the wife longingly watches later. We can explain to ourselves convincingly enough (it is, after all, a convention of melodrama) why a simple farmer should be so completely enslaved by a voluptuous and sophisticated woman from the city. What Murnau never attempts to make convincing on the level of “plausibility” is why the City Woman is apparently so captivated by the man. It’s hardly presented as a case of a sophisticated woman fascinated by earthy vitality, for the man is almost completely passive and all the vitality is the woman’s. She strikes us, in fact, as more a force of destruction than a character, more a Woman of the Marshes than a Woman of the City. She is the nearest in the film to a purely symbolic character. The question is: what does she symbolize?

The fundamental opposition of SUNRISE is not that of city and country. The introductory caption, indeed, warns us of this explicitly, though the surface of the film is so much occupied with the country-city opposition that we tend to forget it. The story (we are told at the outset) is of any time and any place; in country or city, wherever the sun rises, life is much the same. It doesn’t matter very much, on the film’s deeper level, where the City Woman comes from; Murnau’s images tell us that she is a of darkness and the night, an overwhelming vampiric force. The presentation of her (and of the man while he is possessed” by her) carries overtones, subtle but unmistakable, suggestive of horror-film archetypes, vampires, and shambling monster-figures. During the marsh scene, the cut from the shot of the deserted wife on the bed with the baby to the lovers—the man passive, the woman bent over him like a mother—produces a juxtaposition complex in effect; the simple opposition of domestic scene/erotic scene is complicated by the ironic paralleling of two mother-and-child images, one natural, one perverse. When the man furiously rebels against the Woman’s suggestion that he drown his wife, she quite literally overpowers him, covering him like a succubus. There follows a display of rampant sensuality when she urges him to return with her to the city.

I have argued that NOSFERATU can be read as a myth in which Jonathan, as a civilized man, discovers and releases the terrible under-forces which civilization represses and, in repressing, perverts. The depth and detail of its central relationship makes SUNRISE much less susceptible of any such symbolic schematization, yet this and the fact that it reverses NOSFERATU’S terms should not prevent our seeing the profound relationship between two works that are superficially so different. In NOSFERATU, civilization is of the city; the terrible disruptive forces are released out of nature, to spread from the wild mountains back to the town and street where the action began, to confront Jonathan finally with his mirror image across the water (though it is Nina who sees the reflection). SUNRISE confusingly has the dark, destructive forces embodied in the Woman from the City, but there is no doubt where in the film we look for a concept of civilization: in Murnau’s images of marriage and family, in the sense of their sanctity and ultimate value.

In NOSFERATU Jonathan and Nosferatu were symbolically opposed: mirror images, yet mutually exclusive, the one containing no traits of the other because each was the other’s complement. SUNRISE, whatever Expressionist influences linger on in its techniques, moves much closer to naturalism in its narrative method, in its treatment of characters and relationships. The complementary opposition of Jonathan and Nosferatu is resolved in the husband of SUNRISE. It would be as difficult to recognize the young man who kisses his wife at the photographer’s (or the young man of the “plowing” flashback earlier) in the hunched and obsessed monster who lurched toward her in the boat, as to recognize Jonathan in Nosferatu. Yet the extraordinary emotional intensity of SUNRISE’S development compels us to accept that they are in fact the same man—and that the most normal and open and healthy of us has it in him to become a monster.

As with NOSFERATU, though to a greatly modified degree, it is possible to feel that the moral-spiritual outlook of SUNRISE is less than perfectly healthy. The sharp division remains between “pure” love and eroticism. The wife of SUNRISE quite lacks the blanched and angular quality of Nina, the appearance of a female Christ-on-the-Cross, but, although very feminine, she strikes the spectator as decidedly unsensual (an impression to which her tightly knotted hair contributes a great deal). And sensuality, again, is depicted unequivocally as evil and destructive. What was a major reservation about NOSFERATU (about, indeed, the whole Expressionist ambiance) seems at first sight a minor one applied to SUNRISE: it dwindles in relation to the depth and intensity with which the spectator is made to respond to the idea of the sanctity of marriage. The vampire was the center of NOSFERATU, completely dominating the film, the marriage of Jonathan and Nina something sketched in almost peripherally. SUNRISE exactly reverses the relative emphasis. From first to last it is the marriage we are concerned with, its value expressed negatively through all the first part of the film (in our feelings for the forsaken wife and our sense of the unnatural weight of oppression under which the man struggles), positively through the movement to reconciliation and remarriage, to be triumphantly reaffirmed at the end in the face of all the world’s forces of darkness and destruction.

One cannot, however, leave it at that. Moving (and, on one level, convincing) as the film’s overt affirmation is, its partial incoherence (the City Woman’s refusal to be adequately explained in terms of the city) alerts one to the suppressions on which that affirmation is built. I have not so far referred explicitly to the known fact of Murnau’s homosexuality; and there are many good reasons for skepticism about explaining an artist’s work in terms of his personal psychology. The chief one is not that such knowledge is irrelevant, but that it tends to produce assumptions, prejudices, false emphases, a too narrow reading of works that, whatever their roots in individual traits and complexes, may develop implications far transcending their origins. But a point is reached in exploring Murnau’s films when one feels the need for personal reference.