My Big Fat Greek Wedding

The top-grossing independent film of all time marked the latest demonstration of the irrelevance of film critics—like a crowbar to the skull, nobody saw it coming, least of all HBO and IFC. A film about breaking out of the prison house of ethnicity, its scenario is About Schmidt without Schmidt, as crass as anything by Nora Ephron or Barry Levinson. The public gets all the credit for discovering this one: at last, after a deluge of films aimed at dumb teenagers, a film aimed at dumb 50-year-olds. Power to the people.

The Fast Runner

The icemen (and their icewomen) cometh, and you ain’t seen nothing like it. Ever. The fact that a three-hour Inuit-language epic (the first and only one of its kind) managed to fill theaters is only the tip of the iceberg. What makes this complete oddity really matter is absolute ambition: the film turns ancient myth into a magnificent, contemporary digital-video soap opera — a masterpiece of limitless emotional complexity bounded by an infinite horizon. Call it hot-blooded fuel for a frozen cinematic landscape.

Russian Ark/Ten/Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones

Three digital dead ends. 3: An elaborate, sui generis stunt in which dreamy slow motion, judicious color enhancement, and one-shot wonder almost make you forget the effete, airless conception. 2: The odd spectacle of a great visual poet successfully erasing his own handiwork, and successfully attaining the unmediated look of a homemovie shot with a camcorder. 1: Another animated movie with real heads and bodies, banking on the kind of grandeur that only comes in two dimensions.

Far From Heaven

Or the Sirk system. The beauty of the photography—watch closely as souls are destroyed while enveloped in the colors of autumnal decay—counterbalanced by a somewhat ludicrous moral distance, made for an art-house project that broke free from its art-house chains (kind of like cinephilia for beginners). It’s a schizoid affair: if you let yourself fall into the fated rhythms and superb stylizations, you may not notice you’re being lectured to like a child.

Bowling for Columbine

Populist-with-a-bankroll Michael Moore brings documentary to the masses with this funny/serious exploration of gun culture in America. Lefties of the anti-globalization bent blindly rally behind the film, it makes nearly $14 million at the box office by its 10th week in release, and the International Documentary Association proclaims it the “Best Documentary of All Time” (above Night and Fog, Nanook of the North, and The Man with a Movie Camera). But the real question remains: Is Michael Moore the best we’ve got?

The Kid Stays in the Picture

The Vanity Film as Official History: this loving tribute to the bottomless narcissism and remorseless self-mythologization of aging sybarite and ex-studio-head Robert Evans was the very model of sellout-as-career-move. Its makers rendered themselves instantly irrelevant by gratefully trading creative control for access, brokered by the editor of upscale fan mag Vanity Fair in return for a producer credit. Stage-managing his own enshrinement as a Seventies maverick movie icon, Evans exploits a younger generation’s appetite for stories from the Golden Era.

Road to Perdition

For two weeks last summer, you couldn’t turn on the radio or TV, log onto the Internet, or open a magazine or newspaper without having this prestige package disguised as a movie pitched, trumpeted, and pitched again. pr departments, editorial desks, and the filmmakers themselves were in breathtakingly perfect sync, prompting a bewildered “Huh?” from the sorry souls who took the bait. There’s nothing remotely “Oedipal” about it… unless Sam Mendes’s father is named Oscar.

In Praise of Love/The Quiet American

Two vastly different movies embraced by critics if not audiences, after 9/11 had apparently made them off-limits for their ostensibly anti-American sentiments. Noyce’s take on the stealthy postwar expansion of U.S. imperial adventurism would have stayed on the shelf but for Michael Caine’s intervention and positive critical reaction in Toronto—after that, “Harvey” smelled Oscar. Godard’s film, far from Vietnam, took cheap shots at American cultural hegemony to the delight of the U.S. contingent at Cannes in May 2001. Amazingly, it became the first JLG film to get a decent release in the U.S. since 1989, with glowing reviews, none more so than Anthony Lane’s in The New Yorker.

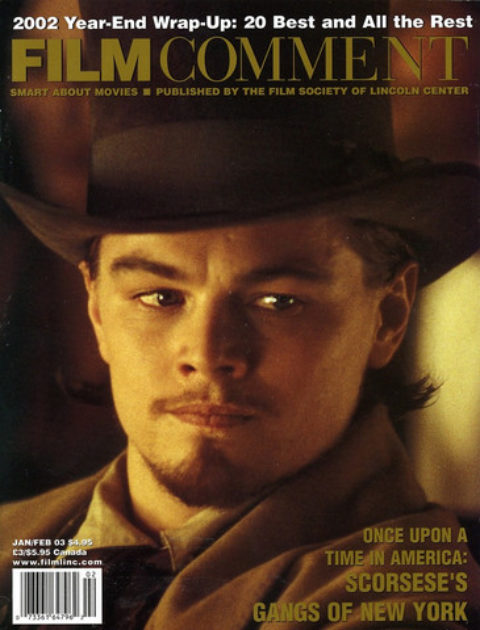

Gangs of New York

We waited and waited—and waited. When it arrived, the result meant something different to everyone: the last hurrah of old-fashioned back-lot moviemaking—the ultimate example of artistic compromise in the face of studio pressure—the first blockbuster film to encompass all post-9/11 uncertainties—the greatest triumph/grandest folly of a bona fide American film legend. In the final analysis, any way you slice it, Scorsese’s writ-in-blood epic is impossible to ignore; it hurtles and pummels and lodges like a meat cleaver through your forehead.