Independents: Missionary Positions

Cinematically speaking, the public display of our sex organs is in the wrong hands. Shouldn’t we reclaim poor, old Eros from the porno houses? Despite twenty years of license to express more on screen, sex in commercial films and on TV remains truncated, furtive, hypocritical, titillating, and fraudulent. Is the enforced absence of realistic sex—the true eroticism of penises and vaginas—any less repressive than women’s forbidden ankles in the nineteenth century?

The truth, of course, is that the euphemistically named Rating and Classification System of the Motion Picture Association of America and the more honestly named Television Code of the National Association of Broadcasters serve as institutionalized systems of censorship, standing between us and the image. That sex and violence remains their real target is an interesting comment on our civilization. Brutality—compared to its incidence—is vastly exaggerated in film and TV; sex—compared to its ubiquity—enormously minimized. Denial of access to sexually explicit films by the MPAA to the young (the largest audience and sexually most active part of the population) represents the time-honored terrorism of the older generation’s attempt to keep sex for itself—just as (and because) it is slipping from its grasp. The economic punishment imposed by the X-rating is quite clear by now; it has eliminated the erotic realism freely available in today’s books.

Print is no more protected than films by the First and Fourteenth Amendment, yet film is more closely self-sanctioned. Is not this precisely what the great American anti-censorship battles and victories of the past thirty years were all about? Having succeeded in abolishing government censorship, are we now to bow down to self-censorship by an industry because its wish to avoid time-and-money-consuming lawsuits against police or state agencies has priority over its defense of freedom on the screen?

It was precisely these anti-censorship victories that led not only to these mainstream self-censorship systems but also to the rise of the new kind of ghetto—the porno houses, and more recently, the porno video market. Our self-appointed censors have it both ways; since these ghettos were assigned the task of “taking care” of morally inferior elements unable to control their animal instincts, their roaring successes must prove that millions of Americans are masturbationists and perverts.

The industry has not only shunted sex into a ghetto, it has actually simulated the production of porno films. These purvey their own kind of artificialities; non-stop sex lacking feelings, feeling-tone, repose, laughter, tension, mistakes. Although, if reasonably well-made, they remain turn-offs for many, porno films present impossible fantasies of endless, seamless, perfect fuckings that have nothing in common with the eroticism of real life or art.

The signification of sexual activity once more becomes sleaziness and “animalistic abandon.” Meanwhile, teenage pregnancies continue to soar, intolerance of gays and lesbians increases as does guilt, while masturbation or sex among older people, the handicapped, the psychologically dysfunctional is swept under the rug of public consciousness.

No wonder, then, that the antiquated MPAA and NAB codes—slighting genuine and deeply human needs—create their own countervailing forces. The very same anti-censorship victories that led to the pornos, also legitimized production of sexually explicit educational films by such social interest groups as the National Sex Forum, an activity of the Exodus Trust, originally sponsored by the Methodist Glide Foundation. The NSF is producing an ever-growing number of films and videotapes in the areas of human sexuality used by over eight thousand colleges, universities, social service agencies, churches, and state and federal institutions. To the repressed (and therefore censorious), the NSF catalogue must appear as provocative (and, of course, a source of illicit pleasure). Its range is astonishing and explicit; the NSF filmmakers include well-known independents and even avant-garde artists. Additional films of this kind are available from other sources. A sampling (not more) of titles follows, indicating their audacious openness to both formal and thematic innovation.

Self-Loving (Laird Sutton, 34 minutes, 1976): Eleven women of heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian lifestyles (of all ages and races) share their experiences with masturbation, vibrators, fantasies, and orgasmic patterns in a warm and intimate series of informal discussion. Their humanity is affirmed by not ever being placed in doubt, and the film imperceptibly and gently persuades us to accept our own humanity as well. The positive statement about women’s sexuality serves as an outstanding conversation starter for women and men of all ages and backgrounds.

Desire Pie (Lisa Crofts, 5 minutes, 1977): A totally explicit “hardcore” cartoon exploration of about fifty humans engaging in possible and impossible couplings, it stresses the interchangeability of sexual acts and protagonists and the universality of it all. Very original, very “obscene,” this significant work was, horror of horrors, made 1) by a woman and 2) at Harvard.

Titles Available (Laird Sutton, 5 minutes, 1972): Practically dribbling with affected lust, a young man declaims with growing gusto and ever mounting speed, 250 possible titles of pornographic books “available at your local book store.” Staring directly into the camera while hurling all possible “forbidden” words at us in deliberately outrageous combinations, he immediately succeeds in “desensitizing” the viewer so that laughter supersedes shock. Miraculously, we become aware of both the emptiness of pornography and its continued power to arouse. This extremely subversive, original work is made doubly provocative by subtitles that duplicate the soundtrack. This may well be one of the clearest, most outright subversions of the sexual taboo in cinema today.

Hermes Bird (James Broughton, 10 minutes, 1977): The great and wise master of the American avant-garde, James Broughton, poet and subversive Buddhist, continues his sly attacks on sexual taboos with this deceptive masterpiece. It employs his customary combination of visual poetry and strongly ideological content. As we stare at an immobile medium shot of a man’s belly and flaccid penis, the filmmaker delivers fervent paean to the organ’s powers and beauty. The camera never moves. In the course of ten minutes of poetry and penis, however, we gradually realize that the Grand Subversive—far from confronting us with a freeze-frame—had all along been offering us the swelling of the member in extreme, imperceptible slow-motion, until at the end a full erection confronts us in all its majesty. Censors and protectors: Take to the Hills! There is nothing as threatening (to you!) than the erect penis. What would our country come to if our defense system consisted of flying armadas of these symbols of life rather than our current missiles of death?

Sun Children (Laird Sutton; 14 minutes, 1974): A young couple, at a secluded, sun-lit beach, undress, engage in mutual oral sex, then intercourse and orgasm, all visible. Despite its “romantic” overlay of location and sound (bird cries and waves), it is a more accurate example of erotic realism than I Am Curious-Yellow, which failed to display actual copulation. Some day—one hopes—the new Bertoluccis, De Niros, and Diane Keatons will be as honest in 70mm color and Dolby sound.

Words of Love (Dirk Kortz, 5 minutes, 1977): This is possibly the most “explosive” film of the lot. Rapidly paced throughout (about a second per shot), it begins with about forty different penises in close-up while a female narrator simultaneously labels them with the most vulgar and obscene slang expression (their number is startling); at the same time, these same “forbidden” words appear in subtitles. Vaginas next receive the same treatment, but with a male voice-over. Then the two come together in foreplay and sex, each stage again accompanied by the forbidden expression, “doubled” in subtitles. Though the apes the codes of instructional documentaries, its shocking subject matter and technique accomplish a different purpose: the demystification of forbidden images.

From personal experience, I can testify that in a university classroom in five minutes the film subverted many taboos. The audience, eyes flashing, immediately and smilingly launched into an open discussion. Sex is a subject everyone wants to talk about and feel comfortable doing so: if it didn’t arouse such strong feelings one way or the other, the MPAA nor the NAB would keep it from us.

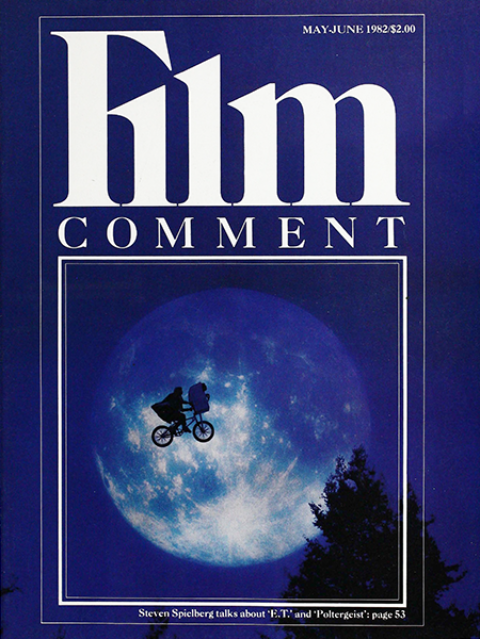

Asparagus (Suzan Pitt, 19 minutes, 1974-8): This powerful erotic allegory of the creative process—a masterpiece of film magic—violates taboos of defecation and oral sex in a manner that integrates these acts into expressions of high art (see my May-June 1981 Film Comment column).

Grow Along With Me (Coni Beeson, 12 minutes, 1974): A 60-year-old couple (married for some thirty years and grandparents) are shown living their alternate lifestyle and enjoying sex.

River Body (Anne Severson & Shelby Kennedy, 8 minutes, 1970): Over eighty nude people face the camera, shown in continuous dissolves. Different heights, shapes, ages, races—and all “the same.”

Other titles include Closing the Circle (sex between a couple in their fifties and a younger male friend); Nick and Jon (gay sex from foreplay to explicit lovemaking); Give It a Try (specific techniques in re-establishing sexual relationship between a recent quadriplegic and his able-bodied wife); and The Squeeze Technique (a graphic demonstration of Master’s and Johnson’s technique for retarding premature ejaculation).

Achieving Sexual Maturity (John Wiley & Son, 20 minutes, 1973): This is the film the Moral Majority attempted and failed to ban, thanks to the unwillingness of film librarians and elected officials to cave in to pressure. A straightforward, conventional, instructional film concerning human physiology, anatomy, ovulation, menstruation, ejaculation, and masturbation, it dispels many myths. A recent Cleveland study of 14,000 parents of adolescent girls showed that sixty percent of mothers never explained menstruation to them, ninety-two percent never discussed sex.

Whether taboos can be removed or only mitigated by rational discourse is a complex question. Freud, the great and somber liberator, hurled some of his sharpest lances at religion, denouncing it as a reactionary, life-denying system of illusion. Yet, in 1982, this religious illusion continues to exist tenaciously. After centuries of repression, it will take much time to make sex into a “natural” subject; to some extent, it is happening. In any case, it seems necessary to support all such efforts so that ultimately articles of this kind will no longer be necessary.