How to Fall Into Oblivion and Take Your Movie With You

The avenue to oblivion is quite accessible really—merely make a movie that’s murder on an audience. It wasn’t difficult for me. I positively aspired to the obscure, the pretentious, and the boring—if you’re prone to that style of judgment. Last Year at Marienbad and L’Avventura were my Grail, and I’ve sat through The Mother and the Whore half a dozen times, and worn out my video of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. So if oblivion is what you crave, for both yourself and your movie, follow me!

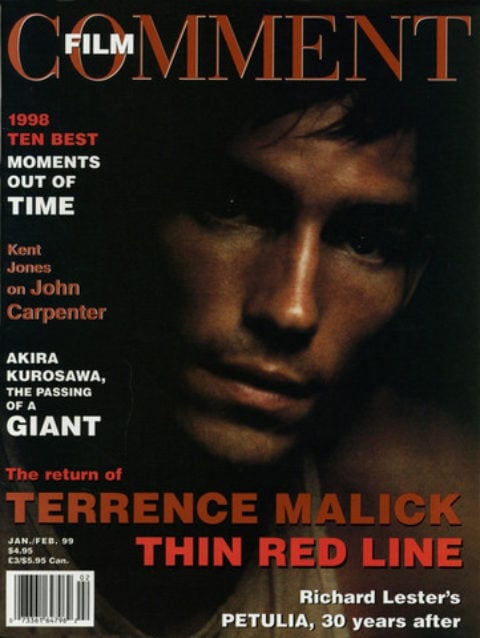

The film I wrote and directed was called Coming Apart, which is what the Museum of Modern Art called its 1998 program of films from the late Sixties, and it starred Rip Torn at his most brilliant. The film could surely use the tribute, having shown theatrically only once since it premiered thirty years ago.

The day Coming Apart opened, the decade had only a few weeks left—everybody had already been assassinated and a man had stepped on the moon. After the first couple of showings, I wandered over to one of the theaters, the one that had once been the Latin Quarter. “How’s the picture?” I asked the first guy out. “Piece of crap, don’t waste your money,” he snarled. If you want to know how I felt, imagine a pediatrician telling you that about your first baby. A couple followed him out of the theater. “How is it?” I asked them. The young woman’s face lit up while her boyfriend answered, “It’s the greatest film I’ve ever seen. We just sat through it twice.” Now imagine the doctor telling you, “It’s the most beautiful baby I ever delivered. I’m not even going to bill you.” I ran from the theater while I was even. What a focus group.

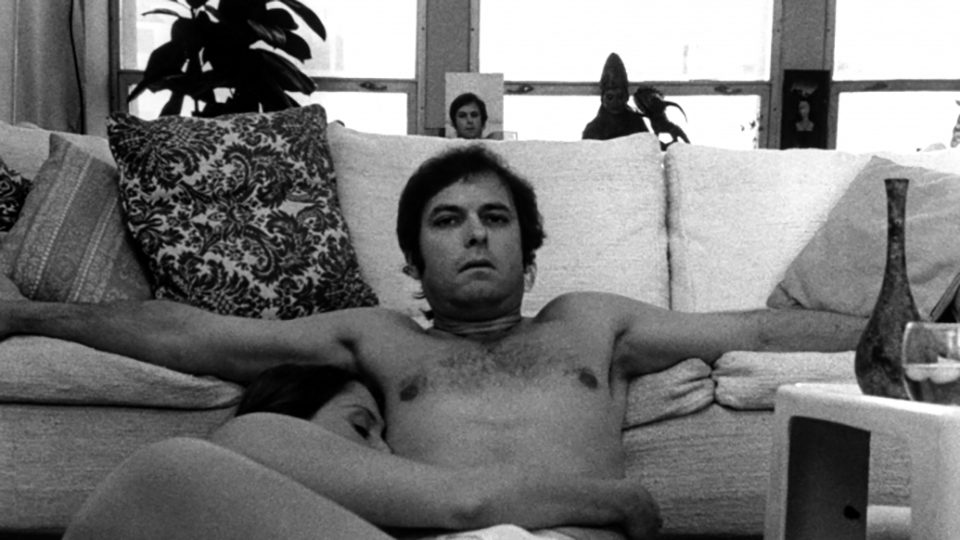

It was a movie quite unlike any other. The entire film took place in a studio apartment and the camera never moved, and nearly all of its action transpired in a mirror. Indeed, the film was about a psychiatrist encased in his own reflection, using a hidden camera to record his own disintegration. The film was also about the pleasures and price of promiscuity, and about the form and duration of reality, and ultimately about the nature of cinema itself—or so I hoped. And to a degree that still embarrasses, it was about me. Appropriate, the title, Coming Apart.

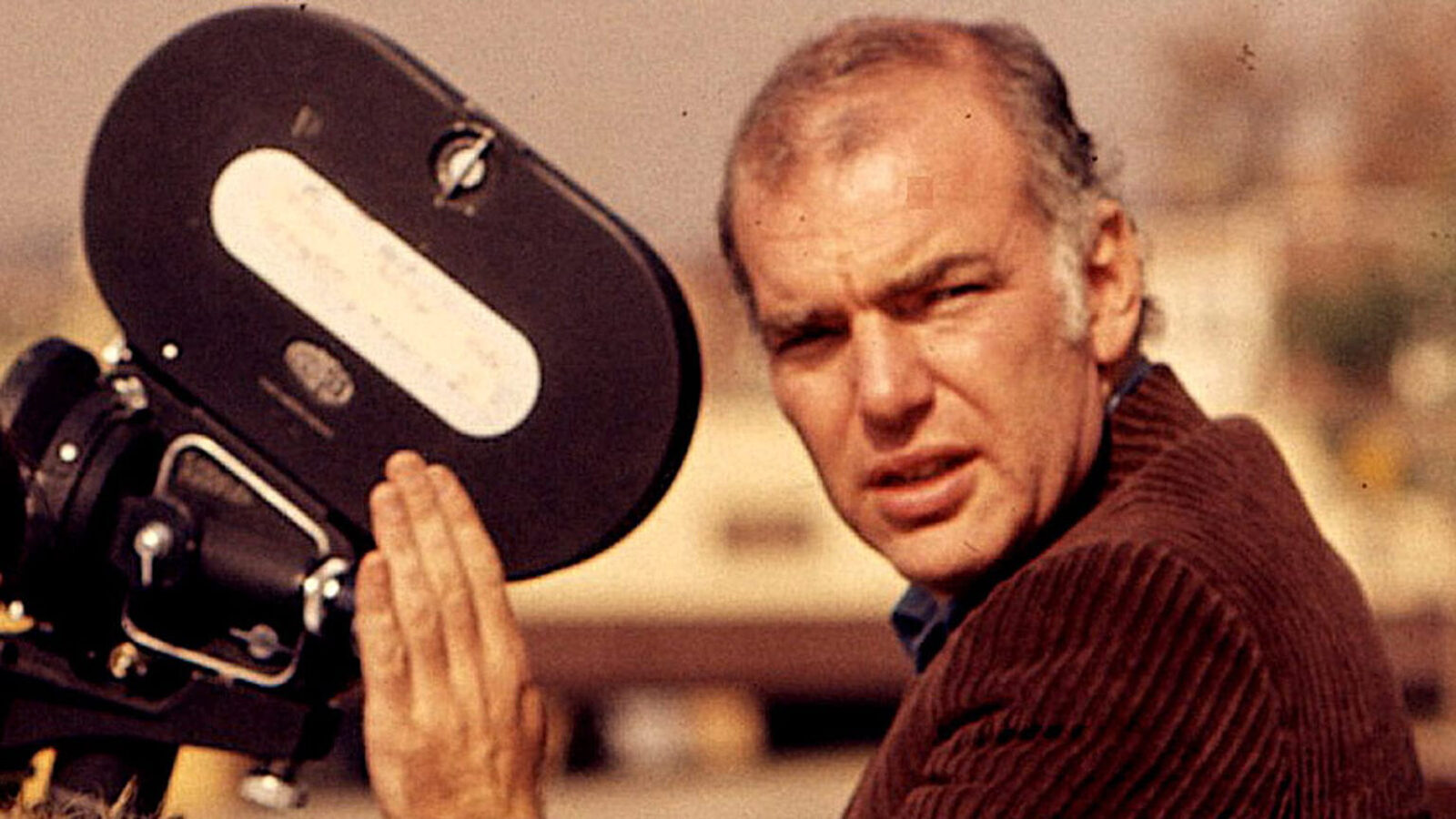

It was a heady, unreal time, 1969, for an assistant film editor. Two producers, Andy Kuehn and Dan Davis, had optioned my first two screenplays. I convinced them to finance a scene or two from one of them to show the studios I could direct. They asked how much I’d need. “Twenty grand,” I lied. They blanched. “But if you double that, I’ll make a whole movie.” “How are you going to do that?” one asked. “I’ll shoot it all in one room.” “Deal!” they cried, then asked, “In 35?” “Easy,” I said. The finished script ran to two hundred pages and appeared as a paperback before the movie came out. I suppose that it was Hitchcockian in the sense that it described every gesture and sigh down to the protagonist’s Mediterranean loafers (courtesy of Purple Noon). And that’s exactly what we filmed.

The device was simple enough—the screenplay had proceeded from a simple drawing of the only shot. A sofa filled the lower third of the frame, and the vast mirror behind it, the upper two-thirds. Shooting into a mirror offered some visual variety. Sitting on the sofa, the actors were in moderate closeup; standing up, they entered the zone of the mirror in wide shot. One odd and pleasing result, when two people spoke to one another, you could watch both their faces at the same time.

The psychiatrist, played by Rip, turned his camera on and off at will, censoring what he would ever have to confront. Most of the uncut scenes ran to ten minutes, and it was left to the audience to figure out how long the camera had been off in between, a moment, a month—one of the narrative premises being, when you listen to your neighbors through the wall, who needs backstory?

Everyone seemed to be seeing a psychiatrist at the time, so another premise was: Who could you trust to hold you together if your psychiatrist cracked? I was deep into Freudian treatment with a doctor I admired, and at the same time I was hanging out with some other psychoanalysts who were rather pathetic and contemptible—if for no other reason than they were leading the same promiscuous life as me. So psychiatry was coming at me in two ways, and I wanted to project a character who suffered this fissure—between the ideal doctor his patients saw, and the faulted one he saw in his minor—to such a degree that he break in two; even a he tries to hold his psyche together by making a film about the rent in his soul. And the great Rip Torn turned his fragmentation into brutal reality.

Sally Kirkland was Method all the way, and I remember telling her, “Look, I want you to let go of your work after every line. Drop whatever emotions you have going for you, and build them from scratch for the next line.” Because I wanted the film to be about time. I was interested in the spaces between the lines—the humanity in nonactivity. It wasn’t exactly your screwball comedy timing.

The shooting lasted three weeks. Viveca Lindfors did both her ten-minute scenes in a day. When you come to the set at 9, and the lighting is finished at five past, you have a great deal of time to rehearse. The scenes were complicated though. If you blew a line seven minutes into a ten-minute take, you had to start all over again.

But for me it was the way to make movies that bore some resemblance to life. And Rip was absolutely thrilling, daring in what he didn’t do, in order to leave room for those intangible presences to bloom.

One of the crimps along the way became particularly painful. I wanted the actors to feel free to do anything, sexual or otherwise, so I told them they could tell me, “Please don’t use that,” after the fact. I had meant within twenty-four hours or so, but neglected to say it. Months later, after a few press screenings, Sally came to me and said Shelley Winter had told her that one vivid scene in the film would ruin her career. It had to do with that other F-word, the one in Latin that rhymes with Hamlet’s best friend. So I honored her request and changed it to something a little less explicit. The press was far tougher on me than they later were on the maker of Fatal Attraction. Perhaps it troubled them that I had made the decision without the sanction of a focus group.

So, were these formal limitations and obscure ambitions sufficient to guarantee me permanent parking in limbo? I had certainly done my homework. If the devices of Coming Apart were simple, its source were a melange of the artistic impulses of the Sixties. It was predicated on the demonic genius of “Candid Camera,” where I had worked as an assistant not too long before—and where every editing room had a closed circuit camera, so Alan Funt could watch his editors while he waited for 1984. And it was influenced by the verite films I used to sync at Maysles—where the numbers punched into the end of every mesmerizing roll jarred me back to reality. And by the static frames of Ozu, and by Ichikawa’s The Key (Kagi), which used CinemaScope to describe the in ti mate landscapes of face and bedroom. Belle du ]our was in there, too, and the explosion in pornography that year, which showed us what we looked like kissing.

It didn’t occur to me until years later that Coming Apart had another cinematic source. Check out this 10-year-old going into the nabe to catch a triple bill one Saturday matinee, and emerging, after seeing Spellbound, an acolyte of Freud. Hitch resonated more in my tender unconscious than I cared to fathom. I fell in love with a graduate of Auschwitz named Miriam because she reminded me of Bergman, then fell in love with Viveca because she reminded me of Miriam, then got Viveca to play a character who reminded me of Monica Vitti. How would you like to have spent that seminal Saturday in my subconscious, pal?

And there was not only Warhol’s static frame, there was Valerie Solanas shooting him. The incident haunted me—a hanger-on shooting a director of reality films. So Sally Kirkland is playing a kind of Solanas, who’s waiting to shoot our hero—after that mirror shatters—and I suppose is waiting still. But Coming Apart‘s most immediate inspiration was Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary, a film that understood the voyeuristic, narcissistic yearnings that secretly motivated every filmmaker.

Ahh, Coming Apart was such a child of the Sixties. Such a confluence of concepts for such a minimal form, such a tiny fulcrum for the Museum of Modernism to bend an era on.

Coming Apart (Moses Milton Ginsberg, 1969)

There was one final source for the film: my life. For starters, I had fallen for a young schoolteacher because she was a dead ringer for Monica Vitti. Everyone thought so, at least everyone who knew who Monica Vitti was. But she wasn’t Monica Vitti and I treated her badly. And after I left her, she found another and I went to pieces. Then one day I looked out of my second-story Madison Avenue window and found her and the man she would marry pointing up at me and laughing. It seemed rather cruel, so I moved into the apartment building in which they lived in order to make a movie—about a guy who moves into his old girlfriend’s apartment building in order to make a movie about it. If you’re that nuts, then that’s what you’ve got to build on. The Man From Angst was back in town!

And that Burn Lady, as she came to be called, that, too, was transcribed much too faithfully from life. I sat across from her in the museum garden months after the film ‘s release. Our glances crossed occasionally, but I never spoke to her and she never spoke to me. Pity, I would have been proud to tell her that I never mentioned who she was to a soul. I tell you now, lady, I’m sorry I divulged this experience, but its shock was a seminal one in my life, and I hoped what I turned it into was art. Indeed, every episode in the film was a correlative for my own sexual curiosity, paranoia, and despair. Thirty years ago I filmed a portrait of myself so darkly intimate, I still find it intolerable.

Coming Apart struck nerves; some of the reviews were virulent. After one press screening, I rode down in the elevator with the reigning doyenne of reviewers, who turned to one of her colleagues and said, “Look at the quality of the paper the book is printed on. If that doesn’t tell you what kind of movie this is…” I knew my trouble would be profound, and I figured I’d better spend the rest of the screenings across the street at the Metropole, standing under Dizzy’s flugelhorn for the price of a Rheingold. Though maybe that’s apocryphal and there were only dancing girls that particular week. Neither could make the time go quickly.

In the end, the savage review killed the film. Finally, I consoled myself, it was a Rorschach. The critics who attacked it were afraid of their own erotic impulses or the stunning lack of them; those who applauded the film were driven by their fantasies, haunted by their darknesses. Personally I can pay no higher compliment. Rationalization, I know, but actually I still believe it. And my designs and motives for the film thrill me now, and I miss them. I made exactly the film I had wanted to make and started my spiral toward limbo. Friends cheered me—I had been twenty years ahead of my time. Now, three decades later, the film seems fifty years ahead of its time, and L’Avventura and last Year at Marienbad and Breathless, a hundred, and both La Maman et La Putain might as well be kissing Léaud on Saturn.

At one screening someone asked why I had made the film. It was not a very forthright way of saying they didn’t care for it. But I think a forthright answer is in order, particularly since I now know the reason. If I had seen Coming Apart in a theater the year before, let’s say—responding to some clue in a negative review, no doubt—I would have thought the film was one of the most visionary I had ever seen, and I would have been devastated that I hadn’t been the one who’d made it. Never mind that it was a box-office failure and so many critics savaged it—indeed, the films I leave the theater wishing I had made usually close after three days. But, sensing this film was in me, not making it would have proven even less tolerable than watching my life during that fierce time playing out so publicly before me.

This essay originally accompanied special screenings of Coming Apart at the MoMA. Kino will reissue the film theatrically in mid-1999. Meanwhile, Mr. Ginsberg has just made a video adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, The City Below the Line.