Journals: Mexico City

The last time I wrote about Mexican cinema for FILM COMMENT was in 1985. A lot has happened in the intervening years. To begin with, the industry as such almost ceased to exist. The production companies that dominated the box office since the Thirties went out of business during the past decade, leaving it in fewer but more artistically ambitious hands.

The numbers changed as well. In the old days, an average of 100 films were produced each year. After the administration of former president Ernesto Zedillo, which began with the economic crisis of 1994, film production dropped to an all-time low. Only eleven features were produced in 1998, the smallest number since the early Thirties. But audiences still flocked to a few of these homegrown films. Newcomer Antonio Serrano’s comedy Sex, Shame and Tears (Sexo, pudor y lágrimas, 98) out-blockbustered The Phantom Menace. That feat offered ample evidence that there was a huge middle-class public willing to pay to see Mexican films at the multiplex. In 2000, earnings by local releases made up 17 percent of the box-office gross, taking an unprecedented bite out of Hollywood’s hegemony. Such developements have jump-started the industry, and new production companies like Altavista, Argos, and Titan have begun to emerge in the last couple of years. Last year there were 28 features produced in Mexico, and this year the figure will probably reach the mid-30s.

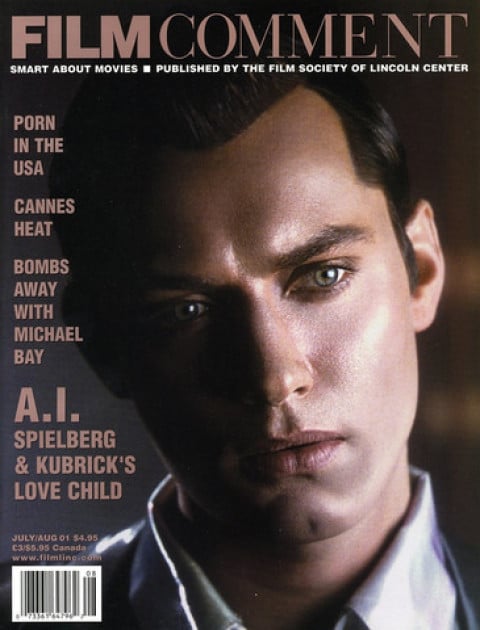

Fifteen of these features were backed by the Imcine (Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía), the state body that continues to be the main source for film financing. An average Mexican production has a budget of roughly $1 million and through a fund program called Foprocine, the state covers about 60 percent of each film’s cost. Directors needing bigger budgets, like Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro (Cronos, Mimic), have found themselves drifting north of the border. Both Cuarón and del Toro returned to projects in their native tongue, to be released this summer: And Your Mother Too (Y tu mamá también) and the Spanish coproduction The Devil’s Backbone (El espinazo del diablo), respectively. Del Toro is already back in Hollywood mode shooting Blade 2: Bloodlust in Prague, a sequel befitting his fondness for the horror genre.

Y tu mamá también

A significant percentage of the new films in production are being made by directors in their thirties, mostly graduates of Mexico City’s two film schools: the national university’s Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos (CUEC) and the state financed Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (CCC). That also accounts for the large number of first features produced each year.

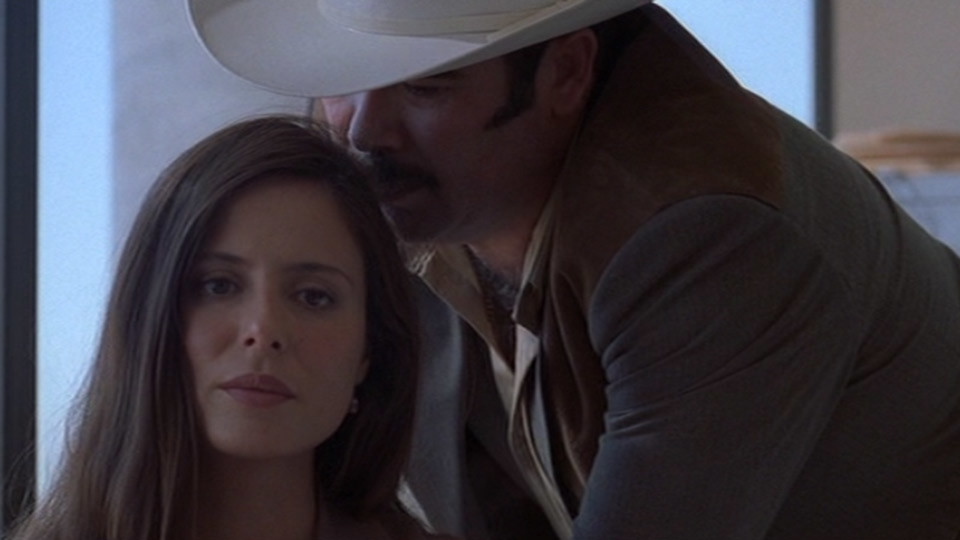

Comedy remains a popular genre, but, interestingly enough, not all of the recent box-office hits have gone for easy laughs. The deservedly praised Amores perros was the top domestic earner of 2000 despite its length and downbeat tone. Moreover, the success of Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu’s debut feature in the U.S. reproduces a feat previously achieved only by Alfonso Arau’s Like Water for Chocolate, with its Mexico-for-tourists approach. Even more surprising was the box-office staying power of Benjamin Cann’s Chronicle of a Breakfast (Crónica de un desayuno, 99). Intentionally irritating, the film depicts the disintegration of a middle-class family in a stagy, hysterical style that somehow managed to appeal to a wide audience. And the political satire Herod’s Law (La ley de Herodes, 00) became a milestone for its portrayal of the PRI, the political party that ruled Mexico for over 70 years, as a breeding ground for corrupt and dishonest politicians. The humor was heavy-handed but effective enough that the authorities tried to put the film on ice; their efforts were thwarted by director Luis Estrada’s shrewd handling of the media. The film proved to be very popular and was even cited as a (far-fetched) reason for the party’s defeat at last year’s presidential elections.

That comedy is the genre of choice is further exemplified by the forthcoming releases of Ernesto Rimoch’s Too Much Love (Demasiado amor), a whimsical approach to a woman’s sexual awakening; Armando Casas’ A Strange World (Un mundo raro), a satirical take on the vices of Mexican TV; Fabian Hofman’s Pachito Rex, a political satire enhanced by its digital aesthetic; and Fernando Sariñana’s The Second Wind (El segundo aire), a lightweight farce about an adulterous triangle. Audiences obviously enjoy the opportunity to laugh at the familiar traits and foibles of a society afflicted by incompetent leaders, urban crime, and an overwhelming sense of enduring corruption. Even when the depiction of national woes is cartoonish, as in Sariñana’s hit Gimme Power (Todo el poder, 00), middle-class spectators find it cathartic.

Herod's Law

Nevertheless, the most interesting films in the 2001 Guadalajara Festival were urban dramas about despairing youth. Gerard Tort’s Streeters (De la calle), adapted from a renowned stage play, explores the mean streets of Mexico City, and focuses on the desperate—and short—lives of destitute kids. A first cousin to Luis Buñuel’s Los olvidados, Tort’s first feature depicts a hellish, nocturnal world of existential dead-ends and sordid violence. At the film’s beginning, the juvenile protagonists ride a Ferris wheel and fantasize about traveling to the sea, a child-like sentiment never to be repeated. Destiny comes in the form of police brutality, double-crossing friends, and a shocking revelation that defeats the youngsters’ dreams. Aided by a restless camera and jump-cutting, the director sustains an in-your-face urgency that never dwells on even the most brutal actions.

By contrast, Marysa Sistach’s Violet Perfume (Perfume de violeta) confronts the problem of rape through the moving friendship between two lower-class teenage girls who develop the kind of deep bond that can only come from camaraderie and non-sexual infatuation. After one of them is raped, her shameful silence breaks their mutual trust with tragic results. Shooting in handheld Super 16mm, blown up to 35, Sistach goes for a documentary directness that avoids any trace of sensationalism: the rape scene is a model of restraint. She presents it as one more everyday violent occurrence in the big city. The plot feels as though it’s actually happening as it unfolds and the final twists never seem like melodramatic contrivances.

Sistach is one of a number of women filmmakers who have staked out territory in an industry that remained male-dominated well into the Eighties. The 21st Century has begun with films by Marcela Arteaga (Memories/Recuerdos), Marcela Fernández Violante (Snakeskin/Piel de víbora), Eva López Sánchez (Francisca), María Novaro (Without a Trace/Sin dejar huella), Dana Rotberg (Otilia Rauda) and Guita Schyfter (The Faces of the Moon/Las caras de la luna). Not bad for the country that put the “his” in machismo.

Without a Trace

As a new generation of filmmakers is busy establishing itself, many of the veteran directors I mentioned in the 1985 article remain active. At the time, Arturo Ripstein was coming out of the worst slump of his career. That same year he hooked up with gifted screenwriter Paz Alicia Garciadiego, and made In the Realm of Fortune (El imperio de la fortuna), starting a streak of inspired films: ten distinctly personal works, sordid stories of doomed love and memorable losers set in Ripstein’s hermetic world of dark shadows and mirroring surfaces. His two latest offerings, Such Is Life (Así es la vida, 00) and The Ruination of Men (La perdición de los hombres, 00), were shot on digital video. Besides its economic advantage, the new technology allowed the director to reinvent his style in a bolder, even playful manner. Such Is Life is an inventive rethinking of the Medea myth updated to a rundown Mexican neighborhood, while The Ruination of Men switches genres and goes for black comedy with absurdist overtones.

As the saying goes, Ripstein is a prophet without honor in his own land. With the exception of his 1999 No One Writes to the Colonel, which had the literary prestige of Gabriel García Márquez’s source novel to coast on, none of Ripstein’s other films have done any business in Mexico (his 1991 film Woman of the Port has still yet to be released). And critical response to his work is much more enthusiastic in Europe and South America; Mexican critics tend to be hostile toward Ripstein’s films, either misreading his intentions or oozing bad will. (Amores perros also received most of its negative reviews in its own country, resulting from the strain of self hatred running through the Mexican press.)

Another figure in the Mexican cinema old guard, Felipe Cazals, came out of retirement last year to direct His Most Serene Highness (Su Alteza Serenísima), a gloomy account of the final days of General Santa Anna, best known as the president who lost half of Mexico’s territory to the U.S. in 1847. Shot with the masterful sense of space that is Cazals’ trademark, the film’s incisive depiction of a decaying form of power that refuses to acknowledge its own end is particularly relevant in light of Mexico’s current political events. Jaime Humberto Hermosillo’s recent, sporadic output has been disappointing: Esmeralda Comes by Night (De noche vienes Esmeralda, 96), a contrived comedy about a passionate woman who expresses her freedom through polyandry, and his latest effort, Written on the Body of Night (Escrito en el cuerpo de la noche), an extremely theatrical melodrama about a wannabe filmmaker’s coming of age.

Still, auteurist aims are diverse enough that it’s still possible to find filmmakers who have chosen to go down less traveled paths. Ignacio Ortiz Cruz, for instance, doesn’t make comedies, although he has a quirky sense of humor, and his settings are not urban but the beautifully barren landscapes of his native Oaxaca. His second feature, Fairy Tale (Cuento de hadas), ranges across more than a century to tell the story of a family curse. An exuberant brew that goes beyond the literary conceits of magic realism, Fairy Tale represents the kind of brash filmmaking that has kept Mexican cinema alive, through thick and thin.