Film Maudit Dossier: Memories of ‘Justice’

There are several varieties of films maudits—films over which hang some dread curse, whether of state censorship, producer’s interference, distributor indifference, or plain bad luck. Sometimes part or all of a director’s career can be maudit; one thinks of Stroheim and Welles in the West, and most of the major Soviet filmmakers in Stalin’s Russia. Sometimes a studio will suppress a film in the sacred name of “tax write-offs,” or bow to the demands of pressure groups (as seems to be the case with Ralph Bakshi’s COONSKIN). And if another company offers to buy the film in question (as film booker George Mansour, Jr., indicates happened with Paul Bartel’s PRIVATE PARTS), the first studio may decide that its own failure with the film would be less embarrassing than someone else’s success with it—and keeps the film moldering in its vaults. The road to film maudit is paved with power plays and cowardice.

These four pages document some recent, flagrant examples of state or corporate censorship—and no matter that the charges against the filmmakers involved range from breach of contract to formalism to trafficking in stolen art objects! Inevitably, our contributors express aesthetic judgments even as they voice libertarian concern, for these filmmakers are artists as well as victims. But the writers here are not telling us what to see in these films maudits. They are simply pleading, with passion and eloquence: Let them be seen!

Jay Cocks (film critic, Time)

With its political issues, THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE is also—perhaps most deeply—about the act and process of conscience. All that it says about history, the judgments the film weighs, become finally subordinate to the evolution and definition of Ophuls’s morality. THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE asked him to reexamine a part of his own life. Ophuls shows the principles established at the Nuremberg trials deflected from the contemporary German consciousness, most particularly, and from the concern of most of the Western World. He calls THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE “a film about the impossibility of judgment versus the necessity for judgment,” a question, a struggle, that Ophuls contrives both to universalize and particularize, within himself.

So THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE is extraordinary, the sort of film that offers the possibility of change. It has been seen, so far, only by the few people represented on these pages. We form a sort of tiny club to which none of us would like to belong without, of course, significantly expanding the membership.

David Denby (editor, Film 73-74)

Marcel Ophuls’s troubles on THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE result from the widespread resistance to accepting documentary as a form of personal expression. It is unfortunately true that the form has served as the refuge for a great many timid and mediocre filmmakers; among these a high percentage have all too willingly embraced the notion that documentary’s authority lies in “objectivity”—one of the most persistent fallacies in the history of aesthetic delusions. To paraphrase Harold Rosenberg’s famous mot, objectivity is simply one of fifty-seven varieties of subjectivity. But because Ophuls’s right to his personal view and method was insufficiently respected by his producers, they saw no reason why he couldn’t be dumped and replaced by another man when they found him personally intransigent. (No matter how much money-men may distrust him, Robert Altman will never suffer from the same kind of insulting treatment.) After all, what is a documentary but a series of interviews and newsreels placed in some sort of intelligible order? Needless to say, it could be infinitely more. THE SORROW AND THE PITY was not only a major act of historical reconstruction, it was one of the outstandingly beautiful moral statements of recent years; THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE is clearly a continuation of that work.

The movie asks the question: How is it possible to judge a nation’s conduct? Do we have the right? Have we lost the right by sinning in Vietnam? The interview material is extraordinarily detailed and bold, the system of organization complex and richly digressive beyond any easy summary. As always, in Ophuls’s films, we arrive at a double view of man as historical actor; he is both free to choose and conditioned by circumstance. Neither freedom nor circumstance rules absolutely, which is why nearly all moral judgments in Ophuls’s films are attained only after the most arduous and responsible exercise of the ethical sense. Included in this sweeping civil process is the filmmaker himself, placed inside history and clearly present in the film as an alert but fallible inquirer. The clear invitation to the viewer to do the same—to use his moral intelligence and see what there is to see—emerges as one of the few imperatives in recent documentaries we can receive without indifference or contempt.

Barbara Epstein (co-editor, The New York Review of Books)

I am appalled that Marcel Opuhls’s brave, serious, important film on Nuremberg is being suppressed.

Lillian Hellman (The Little Foxes, Pentimento)

I think THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE is as brilliant and important a picture as one would expect from Marcel Ophuls, who is one of the great filmmakers of the world.

Mike Nichols (THE GRADUATE, THE FORTUNE)

THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE is a disturbing and finally deeply moving film that throughout its length fascinates, and does not permit judgment of any one of the many human beings who are woven throughout its complicated texture. A fitting epigraph for the film might be Marcel Ophuls’s favorite line from Philip Barry, “The time to make up your mind about people is never.”

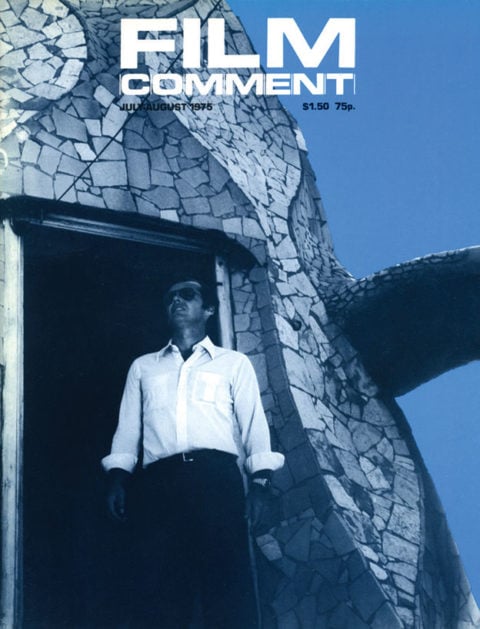

The Memory of Justice (Marcel Ophuls, 1976)

Frank Rich (film critic, New Times)

Marcel Ophuls’s documentary, THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE, at once sums up this historical moment and looks beyond it: it’s a film that bridges the gap between the inevitable climax of our Southeast Asian disaster and that postwar epilogue which is finally ours to make of what we will. Like THE SORROW AND THE PITY, MEMORY is a four-and-a-half-hour exploration of the legacy of World War II, but it has its own special focus. Ophuls is now seeking to understand how the justice dispensed at Nuremberg in 1945 holds up against the test of time—and how the legal and moral principles established then might bear on the Allied powers’ adventures in Dresden, Hiroshima, Algeria, and Vietnam. Ophuls doesn’t have glib answers to such questions—his movie is rich in contradictions, difficult nuances, anguish, and doubt and he constructs his ultimately pro-Nuremberg argument with a scrupulous and painstaking respect for all permutations of the truth.

By weaving together old archive and newsreel footage with dozens of interviews (among the subjects: Telford Taylor, Beate Klarsfeld, Karl Donitz, Col. Anthony Herbert, Sir Hartley Shawcross, Edgar Faure, Yehudi Menuhin, Marie Claude Vaillant-Couturier, Dan Ellsberg, Richard Falk, Dr. Howard Levy, and Barbara Keating), Ophuls covers a large plot of historical ground, but he doesn’t go in for slambang cross-cutting that might allow him cheap ironies; instead he chooses to let the material breathe so his interviewees can (as he puts it) “quit being caricatures and symbols and become people.” The film finds its shape as it goes along, its style reflecting the density and complexity of the issues the filmmaker raises. What finally makes MEMORY so exciting is our sense that we are reliving Ophuls’ own process of investigation and synthesis, and, for that reason, the movie generates that same exhilaration of discovery and revelation we associate with the best fiction films. Once again Marcel Ophuls has given us a classic documentary—a standard against which all other non-fiction cinema must be measured.

John Simon (film critic, Esquire)

Guilt is beginning to catch up with evil in sheer banality. What this means is simply that self-hate is becoming as rampant as hate, and there is hardly a national cinema left that does not exhibit films in which the guilt of the particular nation is paraded with nouveau-riche pride. What makes Marcel Ophuls’s THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE so remarkable is that it sees guilt as something very private and variable within a larger, perhaps immutable scheme. Ophuls perceives guilt down to its very finest gradations, like the abstract expressionists who can paint black on black. He distinguishes among rich varieties of guilt, from bestial to ironic, from avoidable to inevitable, from thoughtless to excogitated, from intensely guilty to all but guiltless.

Yet he is not a pessimist. He sees courage, generosity, and self-sacrifice as sweet, sad, lovely little weeds springing up in the midst of the luxurious flower beds of evil, and his work takes it all in with as much impartiality as is possible for someone who prefers decency to criminality, bravery to cowardice, good sense to madness, in ways that have become quite unfashionable, if not obsolete. What other film about Nazi Germany, for instance, is so concerned with the role of the artists, or of the parent-child relationship, or of the attitudes of the simplest, most ordinary people, in the making or undoing of a totalitarian ethos?

The inquiries about Nazism, Algeria, and Vietnam here are extraordinarily patient, minute, sedulous—nothing is feared more than an easy answer. Throughout, one is aware of the filmmaker’s sensibility: always informed by a profound creative curiosity, open to all possibilities as it delves toward truths that become progressively more unfamiliar, and never relinquishing a basic, subtle smile. A smile, not of superiority, but of melancholy yet bright-eyed awareness: not forgiving everything, which is impossible, but trying to understand it all, which, though equally impossible, Ophuls accomplishes to an astounding degree.

Susan Sontag (Against Interpretation, PROMISED LANDS)

Both as a filmmaker and as a moviegoer, I’m appalled by the sabotaging of Marcel Ophuls’s new film. If THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE were not as absorbing and important as it is, there would be reason enough for indignation. But the film’s great merits make the treatment seem particularly outrageous.

Telford Taylor (Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy)

Marcel Ophuls’s film THE MEMORY OF JUSTICE shows the same probing and compassionate approach which made THE SORROW AND THE PITY one of the greatest documentaries in motion picture history. He deals with problems to which there are no “answers,” and portrays human beings under the stress of conflicting values and emotions, sometimes torn by the tensions of which they are painfully aware, and other times struggling desperately to conceal the issues from themselves. Viewers of this latest Ophuls creation are unlikely ever to forget the experience.