In Memoriam: Kira Muratova

It seems the only proper way to write about Kira Muratova is to write in short snippets, sporadic fits and fragments. As if trying to mimic the way she actually was—fierce, frantic, and controversial. I can hear her voice now. “Why would he suddenly want to write about me? Who does he think he is—a film critic? A journalist? I say, why is he writing about me? He’s merely a filmmaker. This is an altogether different calling. He’s dealing with words now, and words are about something else... But then again, why not? Indeed, why not? He’s started writing, so let him carry on. Let him be. Look how many people there are in this world. And they’re all so different.”

I watched her first two solo films, Brief Encounters (1967) and The Long Farewell (1971), when I was a student at VGIK (Moscow Film School). I remember studying them during editing classes. I remember our professor, Liudmila Petrovna Volkova, giving out sighs of exasperation and shaking her head in disbelief. “This is impossible! You cannot edit this way! It’s against the rules… It cannot work… But look—it does work! It works marvelously!” Hence, the first lesson I learned from Kira Muratova: one always makes one’s own rules.

That second film, The Long Farewell, was “shelved.” In other words, it was banned. As far as a filmmaker is concerned, to ban his film is to ban him, his entire existence: “You are banned. You cease to exist. You can see us, but we don’t see you. To us, you don’t exist, don’t you understand? You aren’t even human, you’re just an empty space.”

What followed was seven years out of work. There was a special euphemism in the Soviet parlance to describe this condition: “forced career break.” Muratova was 37 years old when they told her she wasn’t allowed to make films anymore. Nobody knew how long it would last. One just had to wait… Just wait… Wait and build up energy.

She spent seven years in silence, and then she made her next film, Getting to Know the Big, Wide World (1978)—discovering the world, which does not easily succumb to the act of being discovered. It escapes, disappears, and vanishes. In fact, it’s probably impossible to get to know it. Then, five years later, Among Grey Stones was made. The title speaks for itself. Those “grey stones” did everything possible to force their author to hide in the credits under a nondescript pseudonym, “Ivan Sidorov.” What does it feel like to live among grey stones?

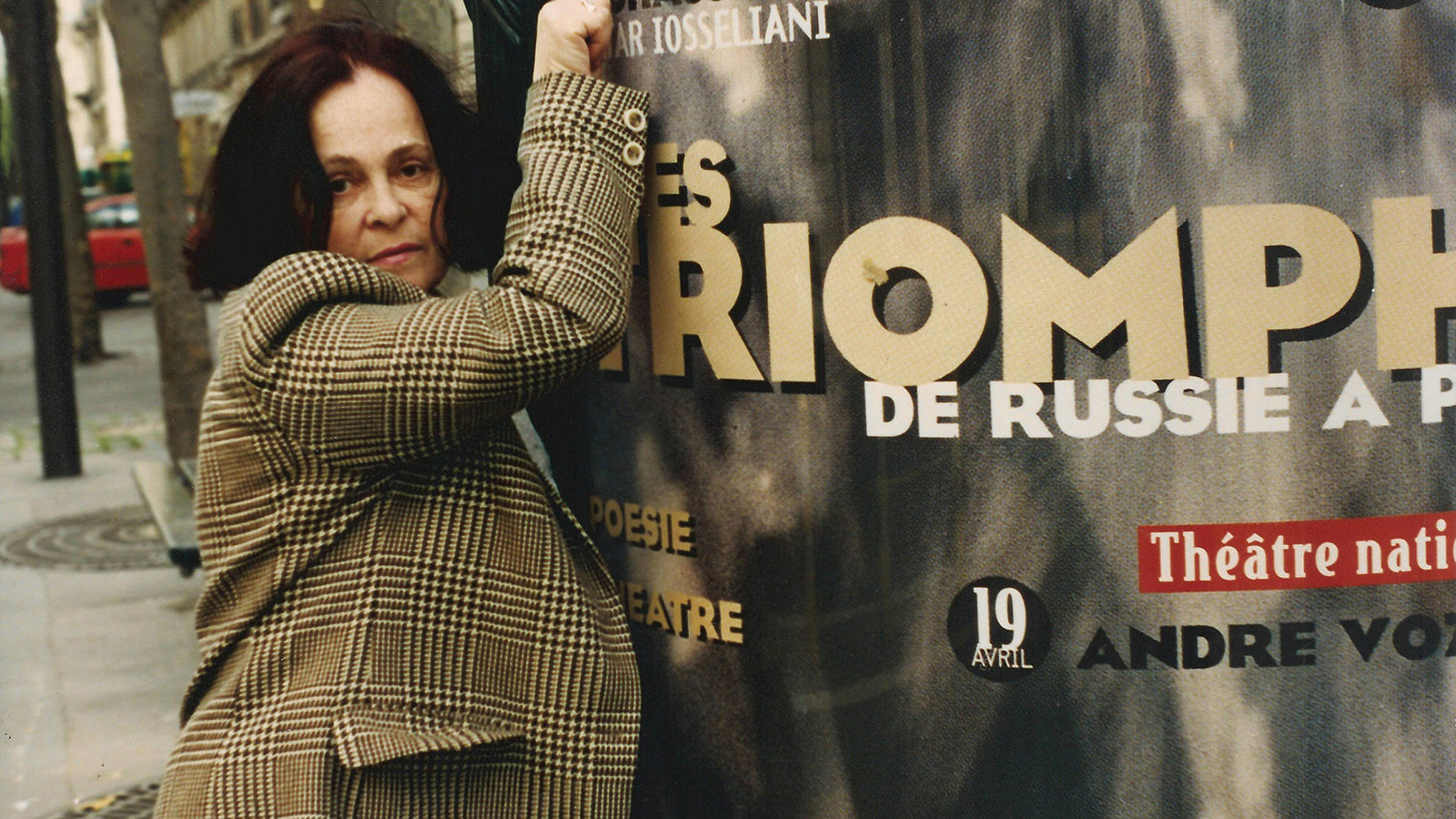

Photos from the personal archive of Kira Muratova and Evgeny Golubenko, © Evgeny Golubenko

And then her luck changed for the better. Something went wrong in the “grey stone” machinery, and all of a sudden everything collapsed—the country and the entire world, which had seemed impossible to discover. The dam burst. With her next film, Change of Fate (1987), again the title speaks for itself. It speaks for her and for the era, which began in her country.

Between 1987 and 2012, during the last 25 years of her career, Muratova made 14 films. She outlived and outsmarted all those who banned her films, erased her from life; who covered their ears and closed their eyes, and screamed in anger. They were all washed away by the tidal wave of new life, and in their place came 14 remarkable films, all of which are on the must-see list for anyone who considers himself a film lover. There aren’t many artists to whom providence gave such a chance. Kira Muratova was lucky. And so were we all.

And then I found myself inside one of her films. In fact, I had been inside her films many times before, but this was the first instance when I became conscious of experiencing a “Muratova moment.”

It happened in Petersburg, in the House of Cinema on Karavannaya Street. Her film Second Class Citizens (2001) was playing. A cinema attendant was standing by the door, hiding behind a dark red curtain. From time to time, she would peek at the screen from behind the curtain, and then hide again. As soon as she realized that I was watching her, she disappeared altogether. I came out of the screening room. She was standing at the door, a middle-aged woman with a bun of blue hair held together by an elastic band with a red rose on it.

I felt ill at ease, and, trying to liven up the atmosphere, I said: “What a wonderful film!”

“There’s nothing wonderful about this film, young man!” she burst out. “How can you even say that! Why do people even bother making this stuff? Who needs this? Who on earth would want to watch this?!”

“But I’ve just seen you watching the film,” said I.

“Young man, I wasn’t ‘watching’ this film. I was working. This is my workplace. And I don’t see how anyone might wish to watch such nonsense by their own free will!”

This monologue seemed to be a direct quotation from The Asthenic Syndrome (1990). The absurd stream of consciousness came from Muratova’s screen straight into our lives and was standing next to me in the foyer of the House of Cinema on Karavannaya Street in the city of St. Petersburg.

What can a filmmaker do? He or she can articulate a point of view. A point of view on what? Well, actually, on pretty much everything. Thus, any film becomes an attempt to redefine things, circumstances, situations, actions, and relationships, which are at once so commonly banal and yet completely new and unknown. Every film—from its opening to its closing shot—offers a key to understanding the world. In this sense, Muratova is a killer with a deadly grip on her subjects and an unfaltering point of view, steadily progressing on her journey of “getting to know the big, wide world.”

I made the acquaintance of Kira Muratova many years later. First, I sent her my films, and she watched them. Then there came an opportunity for a meeting. “Is it you? Yes, it’s you. Of course, it’s you. That’s exactly what I thought—this must be you.” I don’t remember her precise words, but I do remember the tone of her voice. There was no need for words. In fact, it did not really matter what the subjects of our conversations were. Every topic touched upon something much more important, something crucial, something which existed beyond words. Just like her cinema. It’s not really about the theme and the plot, no matter how good and relevant they are. It’s never about concrete people in concrete situations. It’s always about something else—something that remains unsaid and escapes definition.

I can hear her voice now. She’s been lingering in the room all this time. She approached, then stepped away, reappeared, came closer, disappeared again, and finally came up to me. She’s looking over my shoulder. “Has he written anything yet? Well, what has he written? I wonder what it is that he has written about me? I am curious. Yes, I am curious. Just curious, that’s all.”

She exits quietly.

Sergei Loznitsa has made over 25 documentaries and feature films, including most recently Donbass and Victory Day, and in 2013 launched the film production and distribution company ATOMS & VOID.