Fecal Matters

Matthew Barney’s latest collaboration with the composer Jonathan Bepler is, not to mince words, quite literally the shittiest film ever made. Drawing from Norman Mailer’s scatological 1983 epic of Egyptian reincarnation, Ancient Evenings, River of Fundament is more cinematic and aesthetically consistent than The Cremaster Cycle (94-02), is broader in scope, and expands the formal boundaries of theater, opera, literature, and performance art. As formidable an influence on Barney as Harry Houdini (whom he played in Cremaster 2 in 1999), Mailer’s fragile megalomania, macho romanticism, and fixation on buggery all align in one way or another with Barney’s adjacent vices. The adaptation itself speaks to Barney’s notoriously unchecked ambition—who else would have the nerve to take 775 pages of critically maligned purple prose and translate it into a five-hour-plus film boasting hundreds of extras and a river of excrement?

As befits the novel’s plodding, free-form narrative, Barney employs a varied cast of actors to portray the main character of “Norman Mailer”/the dead noble Menenhetet, and his ka (or double), who journey through repetitive fever dreams of death and rebirth. Barney’s outlandish visual sense is attuned to the colorful, hypersexual mythologies of Ancient Evenings, and his depiction of the relentless struggle of Norman’s ka serves as a suitably solipsistic tribute to the author. Scat abounds both on screen and on Bepler’s soundtrack, which combines experimental vocals with eclectic chamber music and sing-song dialogue that rises to operatic crescendos.

Discrete performance pieces feed into the narrative, enacted in the metaphorical wastelands of Detroit, Los Angeles, and New York. A trio of auto-bodies stand in for Mailer’s corpse, and these passages allow Barney to step in and do his thing: breaking down hardware on an industrial scale with the morbid curiosity of an undisciplined child.

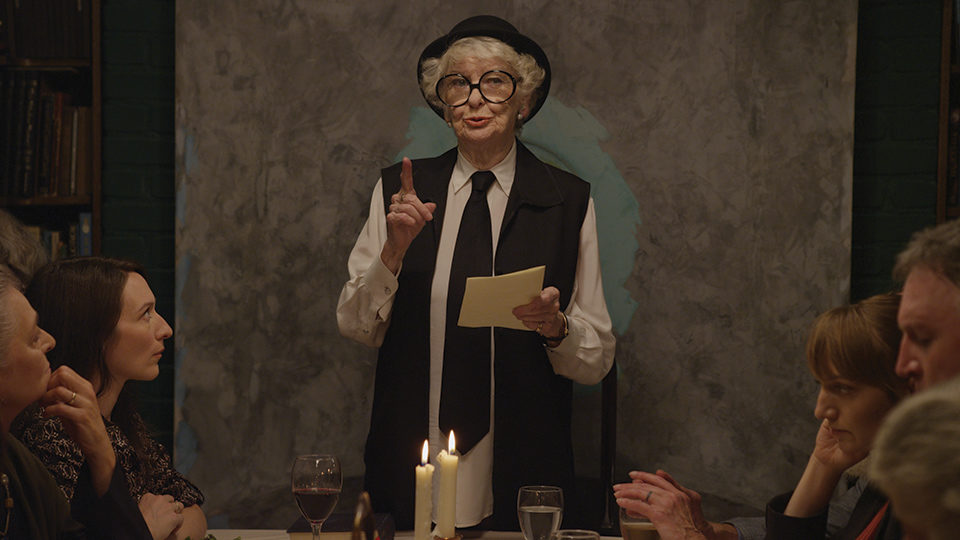

The centerpiece of the film is Mailer’s increasingly debauched wake, set in a replica of the author’s Brooklyn home floating on a barge in the East River. Here Barney celebrates the written word with quotations from Burroughs and Whitman, patched together with passages from Ancient Evenings and the guests’ real-life remembrances of their departed friend. As the river of fundament gurgles and flows downstairs, the camera pans across Mailer’s dusty bookshelves and personal knickknacks with quiet reverence. An astounding congregation of actors and non-actors, celebrities and literary lions stumbles in and out of boozy conversation. Looking ridiculous under layers of heavy makeup, Paul Giamatti introduces himself as the Pharaoh Ptah-Nem-Hotep, while Salman Rushdie, Dick Cavett, Fran Lebowitz, James Toback, and others take their turns eulogizing Mailer. With the exception of a dazed Maggie Gyllenhaal in the role of Mailer/Menenhetet’s mother/lover Hathfertiti, all of the big names have left the room by the time the shit really starts to hit the fan.

Beginning with an early bathroom scene that introduces us to the recurring leitmotifs of sodomy and excrement, nausea-inducing images successively appear like anxious labor pains, building up to an excruciatingly non-cathartic (re)birth. At one point, beneath the cacophony of bodily functions and aboriginal scat-calls, I could have sworn I heard Pasolini turning over in his grave.

Following prolonged sittings, our brains tend to reassemble films of long duration into quantifiable pieces in an unfortunate shorthand. By my own tally, though much of Fundament is quite brilliant, at least two hours of it are utterly repulsive. That’s not to say that two-fifths of the film is bad, but certain scenes cannot help but color the overall impression of the work.

Given his prevailing interest in human anatomy, I imagine Matthew Barney would agree that the exercise of the gag reflex inevitably hinders the process of critical thinking. River of Fundament is a film that surpasses the artist’s previous work, but its extended wallows in shock are more sewage than sublime. And for all his talent, Norman Mailer was not the Marquis de Sade of the 20th century.