Matters of Life and Death: Nadav Lapid

Winner of the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, Synonyms is 44 year-old Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s most personal and provocative film to date. No stranger to subjects of thorny sociopolitical consequence—his first two features, Policeman (2011) and The Kindergarten Teacher (2014), center, respectively on a member of a counter terrorist organization and a school teacher gone to dangerous lengths to protect a budding poet—Lapid boldly casts a critical eye on contemporary Israeli culture. Set in early aughts Paris, Synonyms finds the director expanding his purview through a story based partly on his own experiences as an ex-soldier living in self-imposed exile in France.

Starring first time actor Tom Mercier as Yoav, a disillusioned young solider obsessed with erasing his Israeli origins, the film explores notions of identity, heritage, and masculinity in viscerally direct yet enigmatically plotted fashion. The film opens with Yoav arriving to an empty apartment; as he showers, his clothes are stolen and he’s left naked and alone in the curiously unpopulated building. He’s soon saved by his neighbors, a young French couple (Quentin Dolmaire and Louise Chevillotte) with whom he strikes up an ambiguously motivated relationship. Vowing never to speak Hebrew, Yoav studies the French dictionary and looks for odd jobs by day, and commiserates with friends and fellow soldiers by night, each of whom has a very different conception of how to live and survive as an outsider in a foreign country.

Seemingly incapable of filming a visually uninteresting scene, Navid Lapid continues to refine his highly muscular compositional sense, which can turn even the most mundane encounter into a moment fraught with energy and tension. Like Yoav, his camera is constantly on the move, shadowing his subject as he careens through Paris with seemingly little motivation other than an innate impulse to outrun his past. Political but never didactic, the film picks at a decidedly modern existential condition that, as Yoav’s parable-like journey suggests, may only lead to more unanswered questions.

Two days before Synonyms won the Golden Bear at the 69th Berlinale, Lapid sat down to discuss the personal experiences that inspired the film, how truth in cinema is related to chaos and contradictions of everyday life, and how his late arrival to the medium has informed his unique filmmaking style.

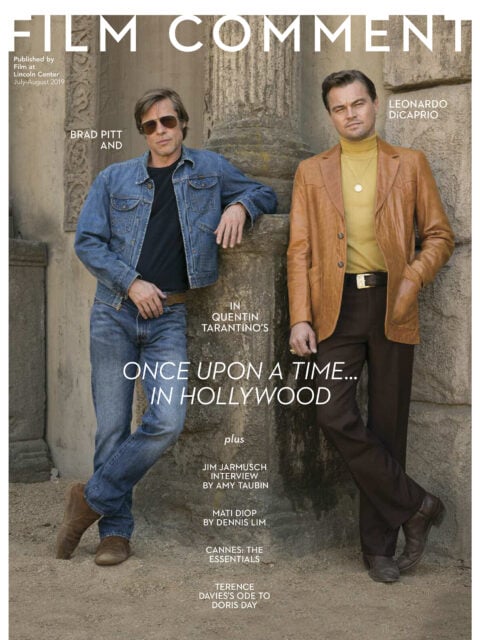

A shorter, edited version of this interview appeared in the July-August 2019 issue of Film Comment.

Nadav Lapid. Photo courtesy of Kino Lorber

Can you tell me a bit about the personal experiences that inspired Synonyms?

The film is based on personal experience in the sense that more or less all the things that occur in the film have really happened. Sometimes in different versions, sometimes closer to my experience. For example, like everyone in Israel, I served three or three and a half years in the military. When I completed my service, on one of my first days out, I colored my hair platinum as a way of telling myself it was over. And that same day I had job interview at fashionable magazine in Tel Aviv. In the evenings I’d grab a beer with a friend, and it was strange because it was as if nothing had ever happened. It had been super intense for three years in the military, moving to live somewhere else, on the border, in the belly of a mountain, in a life that has nothing to do with the one you’ve previously led. And then it’s over and you go back to your normal life and you have to reinvent yourself, because when you started you were in high school and you were a different person. So I did: I studied philosophy in university, and I began writing novels, and I started working for a newspaper, sometimes writing reviews—but not film reviews. At that time I knew nothing about cinema. I didn’t know that films had directors. Like most people in Israel, I’d seen some American movies, but I thought that cinema was a thing for people who don’t have a capacity for abstraction. I felt more connected to literature.

But at some point, about a year and half later, I had an epiphany, this feeling that I must run away and never come back. It was like a vision, like that tale of Plato’s cave, where if someone gets out and sees the light, they’re unable to go back, because when one goes back, they kill you. I felt like I was the only lucid person surrounded by blind people. I knew I needed to leave Israel but I hesitated about where I should go. And it was a big decision because it’s as if this new place was where I was going to live or die. I considered New York, but it felt to me too much like Israel in a strange way because it was full of Israelis. So I chose Paris because, well, mainly because of my childish admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte. I landed at Charles de Gaulle [Airport] with no practical plans for the future but with a clear idea that I was going to leave everything behind and become French. So I stop talking in Hebrew, and that was strange. For a while, for a month or two, I talked with my parents in English, but then I stopped talking in anything but French.

Did you consider that a political decision? Does Yoav?

It depends how you define political. I don’t think that it’s political in the narrow sense of Yoav simply opposing Israeli politics, like if there was a new guy in power and things changed then he would also change his mind. I think Yoav has a problem with what he feels is the Israeli collective soul, the DNA of the place, the melody, the existential music of the state. He ran away from Israel as someone running away from a demon, as if he saw the worst demon. And in that sense there’s a logic in refusing to speak in Hebrew, because the words contain the same sickness. Israel drove me crazy and I told myself, “What does it help if you run away but keep on speaking the language of the devil?” I had this hope that if I kept on doing it for several years, that I was going to open a newspaper, like Libération, and on the fifth page there’d be an article about Israel, and I’m going to read half of it and I’m going to get bored, I’m going to be indifferent, and I’m going to skip over it. This is in some way the state I wanted to achieve. So [the film is] very personal. It’s life material, only served in order to create something.

Where did you find Tom Mercier, who plays Yoav, and what was the process of working with him on the character?

I think when you do a movie that’s based on your own life, even twenty years later, you kind of feel like it should have been you [on screen], even though it’s impossible. You feel as if you give up something—like somehow, if it were me, it would be even better. So you need someone really different, marvelous, almost legendary, in order to make you give away your conception of your younger self, to abandon it, to a totally different version. And Tom is a different version—I was not like this when I was this age. People say that we look a bit alike, but otherwise no, this is not me. He had never acted in a film before. I cast him from an audition—the first scene of the movie was the first time he had ever faced a camera. And it was marvelous because he was totally naïve and ignorant—he didn’t know anything about anything. He didn’t know that the camera had a lens. At one point he was behind the camera thinking that we were shooting him. But when he came to the audition the casting director and I were amazed, because of his strange obsession for details, for the details in the script. He knows every letter, he analyzes—he’s a little bit like religious people in Israel who only read the Bible because they believe if you read the Bible enough, if you get deeper and deeper, all the wisdom you’ll ever need will be revealed. He’s not one of those actors that suggests other things that aren’t in the script. For him, everything’s in there, and if you dig deep enough you’ll find it. And at the same time, it’s inside this obsession that he finds total liberty. The places he takes the script are so extreme that in the end it becomes a form of total liberation.

That seems perfect for the character, that kind of obsessive sensibility.

Yeah, and he’s really one of the strangest people. If having a soul or mind is to see things differently, I’ve never seen someone who sees the way he does, in the most instinctive way. If a few of us would sit around a table, and afterward I would ask him, “How was it?” His answer would always astonish me. But it was always very sincere. I think that at all times he’s inside truth, rooted inside the truth. But then he gets so near to the truth that you have to ask yourself how is he not burned by this fire.

When in Paris did you have similar experiences as far as your acquaintances or colleagues acting in similar ways to how we see some Yoav’s friends acting, such as taunting people or screaming out loud that they’re Jewish?

I worked for for two weeks at the Embassy in Paris and there was exactly this same guy. He came to Europe in order to reveal the real face of xenophobia—he was convinced that the world outside of Israel is composed only of anti-semites and he came over in order to prove this theory. He was convinced that the moment that he got off the airplane that people would do a Heil Hitler. But of course no one did, so he had to provoke them so they would express their real nature. So in the end maybe he was right, I don’t know

Your films seem like they’re very structured and well conceived beforehand. Are these structures part of the script, or are some of these structural decisions made during the shoot or in the edit?

Yeah, the structure was built into the script. But I must say that sometimes I feel like I don’t have a sense of measure. I don’t know where to stop. When you make movies about obsessive characters, you yourself become a kind of an obsessive director, and your cinema becomes an obsessive cinema. In all my movies there are days of shooting that are thrown away even though the scenes are sometimes very good. I think the most beautiful sequence I’ve shot in my life was for Policeman, and it was entirely thrown away. For this film it even went further: there were least two or three other side plots that existed in the script. It was like War and Peace. There were some side plots that were so large—the first rough cut was maybe five hours. But at some point in the editing I understood that the film demanded to be condensed, and at that point the nature of the film changed a bit.

Synonyms (Nadav Lapid, 2019). Courtesy of Kino Lorber

Is it also in the editing where some of the more unresolved plot or character elements are found?

This is also something that existed in the script already, but the more I focused on the film, the more I felt that it’s a film about a certain existential condition, an existential music, a kind of mood, a state of mind, which is at the same time intellectual, emotional, physical, and verbal. So I told myself that I should do whatever I could do to emphasize this state of mind or create these contradictions that could stress this theme even more. And whatever doesn’t should be left behind.

I’m wondering how much of the film’s bigger set pieces are mapped out in your head beforehand? The scene where Yoav dances on the bar, for example, features some pretty elaborate choreography. Is this something you map out on set with your cameraman?

No, I’m thinking about it before we’re on set. For me these are the most moving moments of filmmaking and the moments that you start to understand what the camera will have to say about all this. In preparation, I need to fill my head with cinematic images and cinematic movements, so I watch like, twelve or thirteen films a day. But I don’t watch them from beginning to the end. I fast forward until I see something that interests me. It’s unfair of course, but in a way when you do it like this, at a certain point it becomes like a radiography of cinema. You throw away the plot, and then you deconstruct the cinematic structure and you understand that all the films, 99 percent of them, look more or less like the same movie. Suddenly it’s like looking at the nuances between Perrier and Evian, and it becomes very clear which films are in the 1 percent. Not that it’s your duty to do something special, but I think that if you try to grasp the truth of the moment then something special can transpire. In my head the truth of the moment is connected to its chaotic aspect. And this is the problem with the great majority of movies, that they cannot grasp the chaos and the contradictions and the strangeness of existence. They are determined, they want to say something, but then the films still end up sterile by default. Most films are too sterile. I’m thinking with my camera months and months beforehand. Once I come to a general understanding of the moment, and develop a general feeling, that’s the moment when I can best contradict it.

How did you come to the idea to film Yoav’s walking scenes as trick POV shots, POV shots that reveal themselves to not actually be filmed from Yoav’s perspective? And why shoot them with a noticeably lower grade camera?

All the walking sequences, these sequences of wandering the streets of Paris and mumbling words and synonyms and so on, it’s something that was in the script but I didn’t know how to film it exactly. I realized that it should be treated differently, because it’s something that is complicated to do in the frame of a conservative shooting plan. I told myself that these moments aren’t worth anything if they don’t touch something, if real life doesn’t penetrate inside them and create, and give, put a stamp on the movie. And this is something I was concerned about, because what do you do if you arrive to a location and it’s not happening, if it’s not working? We did these sequences on the weekends, and sometimes it was only myself and the actor, and sometimes it was myself, the DP and the actor—we were always two or three. We understood from the beginning that there should be a kind of break there, and the break could be visualized by using a different camera. A lot of things are happening in the movie, and I felt a kind of strangled by the amount of activity and events. I felt I needed a routine, or a motif, and the routine were these walks and the recitations of the words—these became really essential moments in the movie. And it became somehow logical that these would be both point of view shots and not point of view shots, because there isn’t a traditional cinematic grammar for moments like these that are all movement and words and thoughts.

You mentioned that you came to cinema somewhat late. Do you think that played a part in the openness or liberation you feel while composing shots and conceptualizing sequences?

I don’t know if its lucky or not, but I’m not one of those kids who grew up with cameras. I never touched a camera until I arrived to film school, when I was already 26 years old, and by then I had already published a book of novels. This was one year after I came back from Paris. And I didn’t grow up on, I don’t know, Spielberg movies like most of my friends did in Israel. All the professional aspects of cinema never seduced me, never attracted me. So there are a lot of things I feel a little ashamed of. For instance, I never regret the fact that film disappeared and you have to shoot with digital—all these things seem to me a little bit vain. I can understand that there are people who can relate to it, since they’ve used it for years, but I’ve always thought of cinema as a way for me to express sensitivities, things that I felt inside, ideas or thoughts. And this relates to Synonyms because it was in Paris where I discovered cinema. It’s where my friend Emile introduced me to cinema, and where suddenly I discovered cinema as an object of discussion. We went to see films together, and I couldn’t wait for the film to end so we could talk about it. And he explained to me basic terms and techniques. It’s from him I that heard for the first time terms like shot, sequence shot, cut, mise-en-scene. I was so isolated that I thought that the main thing that people do in their lives is to talk about mise-en-scene! So it was a strange process of discovery, but for me, from the very beginning, cinema was simply a wonderful option to express something.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.