The River’s Roar

Whack fol the da O, dance to your partner

Welt the floor, your trotters shake;

Wasn’t it the truth I told you?

Lots of fun at Finnegan’s wake!”

—Traditional Irish Song

A dead man lies in a coffin. Mourners drink and dance around him. Suddenly, the man sits up. The mourners push him back down. Thunder cracks. Buildings collapse. A bride runs through the city streets. Roses float on the water. These high-contrast black-and-white images, in evocative collage, make up the texture of Mary Ellen Bute’s 1966 film Passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Filmed in Dublin and the Ted Nemeth Studio facilities in New York, with an Irish cast, it was a labor of love for Bute, a longtime member of the James Joyce Society, who made her name as an experimental abstract animator in the 1930s. Bute collaborated on the screen treatment with Irish actress and playwright Mary Manning, who had already done an adaptation of the book for the stage. Further work on the script was done by Bute, Ted Nemeth, and Romana Javitz.

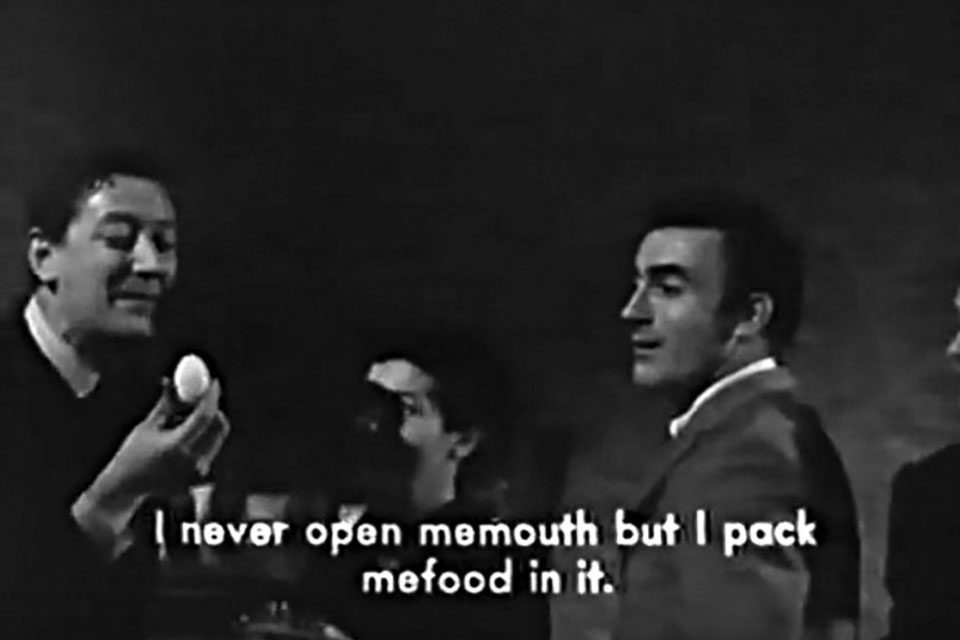

As challenging a reading experience as Finnegans Wake can be, in a way it is James Joyce’s simplest creation. It’s 628 pages of puns and word games. The sound of the words is the star. Joyce had terrible eyesight: he “saw” the world with his ears. The language in Finnegans Wake can look like gibberish on the page, but meaning arises when you sound it out. (“Arthurgink’s hussies and Everguin’s men.” Say it out loud. If you need a clue: Humpty Dumpty.) As Joyce writes in Finnegans Wake, “The speechform is a mere sorrogate.”

Speech had always been a “mere sorrogate” to Mary Ellen Bute, too. In 1956, she published a manifesto in Design magazine called “Light * Form * Movement * Sound.” In it, she spoke of what she called “Absolute Film,” saying, “We view an Absolute Film as a stimulant by its own inherent powers of sensation, without the encumbrance of literary meaning, photographic imitation, or symbolism.” Her desire to “bring to the eyes a combination of visual forms unfolding with the rhythmic cadences of music” is a perfect marriage with James Joyce’s most aural of novels. She wanted people to see with their ears, hear with their eyes. Of Joyce she said, “We’re traveling on the same terrain.”

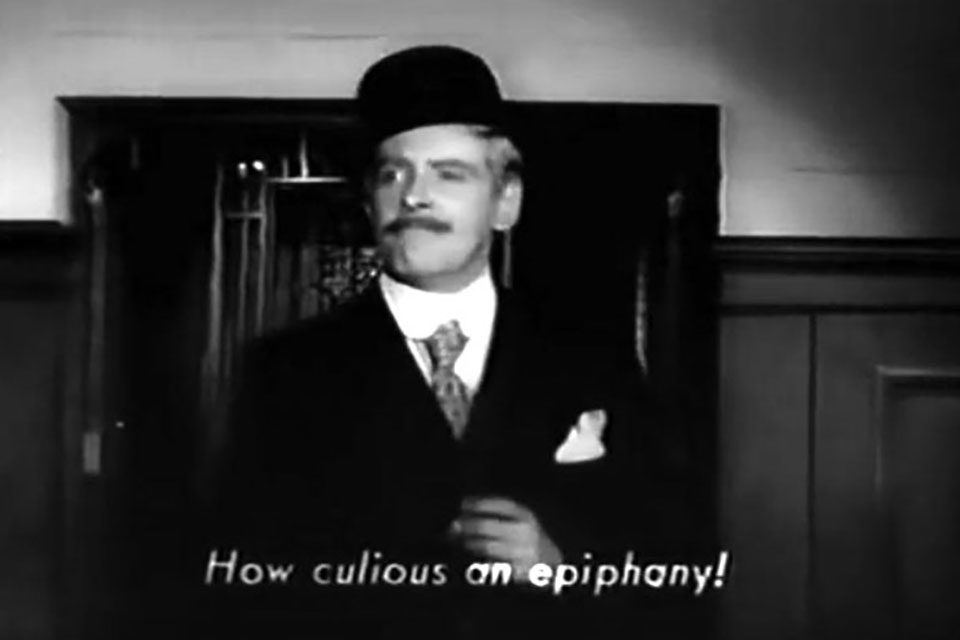

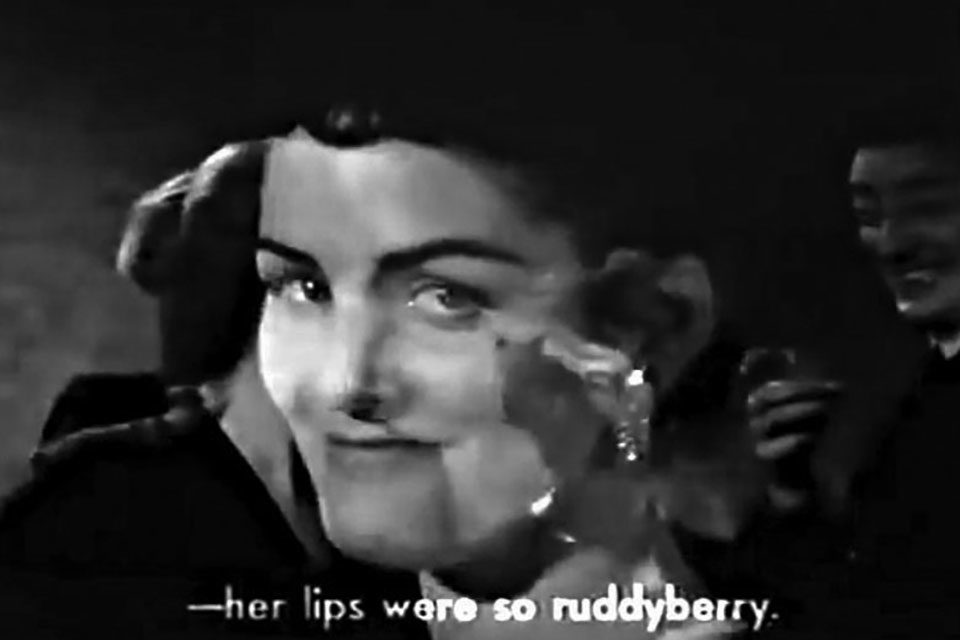

Passages is an attempt to re-create the book’s linguistic inventions through the use of montage, collage, and music. Since Finnegans Wake is about a man going to sleep, it’s almost the platonic ideal of “universal.” Bute was fascinated by the malleable quality of the text, how each reader has a unique “way in.” The text shifts, depending on your entry point. Bute’s version has aspects of a variety show: she incorporates theater, singing, magic tricks, soliloquies, a burlesque bump-and-grind. She even includes a “television commercial,” with a woman advertising cold cream while lying on a zebra-striped rug. In a 1964 interview with Film Culture, Bute said, “The film is not a translation of the book but a reaction to it.” Yet there’s not a word in the film that’s not in the book. One of her most important choices was to use subtitles, showing Joyce’s spelling of what was being said on screen. It makes the point that Finnegans Wake’s language may look incomprehensible, but when spoken out loud it’s really quite clear.

Briefly, Finnegans Wake charts the progression of a man named H.C. Earwicker from waking state to unconsciousness and back. As he sleeps, his wife (Anna Livia Plurabelle) and three children (Shem, Shaun, and Issy) dominate his subconscious. Earwicker journeys from pre-history across time, accompanied by a parade of Ireland’s heroes, mad saints, and warriors. When morning comes, Earwicker wakes up refreshed, whole, integrated (“himundher manifestation and polarised for reunion by the symphysis of their antipathies”). Earwicker fractures during sleep. So does the language. Samuel Beckett observed: “You complain that this stuff is not written in English. It is not written at all. It is not to be read—or rather it is not only to be read. It is to be looked at and listened to. His writing is not about something; it is that something itself.”

Being Irish, Joyce was acutely aware of growing up in a country that had been conquered, whose native language had been suppressed. The problem of translation consumed him. As a young man, he learned Norwegian so he could read Ibsen’s plays in the original language. In Ulysses, he attempted to create a “language which is above all languages, a language to which all will do service.” Finnegans Wake was published 17 years later, in 1939. His wife Nora, staring at the marked-up manuscript, asked, “Why don’t you write books people can read?” After Joyce’s death, Nora said to an interviewer in frustration, “What’s all this talk about Ulysses? Finnegans Wake is the important book.”

Bute, a self-described “Finnegans Wake girl,” agreed with Nora. Born in Houston in 1906, she started out as a painter, inspired by Kandinsky, Klee, Picasso. Frustrated by painting’s limitations, she studied stage lighting at Yale before transitioning into animation in the 1930s (a heady time for the medium, culminating in the triumph of Fantasia). Bute experimented with an oscillator, worked with sculptors, musicians, other animators (her short Spook Sport was a collaboration with Norman McLaren). Her producing partner was Ted Nemeth, whom she would eventually marry (he would be the cinematographer for Passages). Many of her shorts played in theaters before the main attraction, similar to Pixar shorts today, so millions of people around the country saw her work. She is not as well-known as she should be at present, because what she made remains hard to see.

Since so much of joyce’s work takes place in the eddies of human consciousness, it is difficult to adapt him to a visual medium. John Huston captures the feel of “The Dead” in his 1987 swan song, but when it came to the famous final paragraphs of the short story, he threw up his hands and had actor Donal McCann read it in voiceover. The “Nighttown” section of Ulysses—already in script form in the book—was turned into a play, and in 1967, Joseph Strick directed a film adaptation of Ulysses, almost as controversial as the book’s publication. (My father remembered having to drive out of state to see it, since so few theatres dared to show it.) Finnegans Wake, with its complete interiority, requires a surreal and abstract approach.

Bute uses her animation background to explore the text of Finnegans Wake: it’s a playful book, and so she does not take a somber approach. The action speeds up, slows down or runs backwards. She uses still photography and newsreel footage. Images repeat: eggs, light, water. Including Bute, six editors worked on the film, one of whom was a young Thelma Schoonmaker (it is her first credit). Bute has a lot of fun finding ways to theatricalize Joyce’s cacophony of words, inventing scenarios from which the language would emerge. And so a television news anchor gives a report on the events of “1132 A.D.” A vaudeville troupe performs “Tristan and Isolde,” complete with soft-shoe routine. Two loinclothed cavemen bicker. A politician rides in an elevator, giving speeches to an increasingly hostile crowd on every floor.

Martin J. Kelley, with lilting expressive voice, plays Earwicker. Jane Reilly plays Anna Livia, a mercurial personality (in one sequence in the book she literally turns into all the rivers of the world), and Peter Haskell and Page Johnson play Shem and Shaun. The actors had the daunting task of speaking Joyce’s language, but it helps that Joyce wrote much of it in an Irish accent. It’s colloquial speech coming out of an oral tradition. Quicksilver transitions send the action leaping around in space and time. The news anchor asks his audience at one point: “Where are we at all? And whenabouts in the name of space?” The film is filled with music (outside of Elliot Kaplan’s swooping score): the cast sings Irish ballads, hymns, drinking songs. Sometimes they sing the language itself.

Bute’s film played at Cannes. Some scholars chastised her for dragging Joyce down into the muck, but such snobs ignored his love of pop culture. (Mutt and Jeff are recurring characters in Finnegans Wake, after all.) Joyce was fascinated by cinema, too. In the early 1900s, while living in Trieste, he decided to bring the exciting new art form to Ireland, and so he started the Cinematograph Volta, operating in Dublin. His involvement was short-lived, but it shows his interest in the “now,” in the future—in art for all, not just the elite few.

Finnegans Wake is filled with references to ears (including the lead character’s name). “Ear” is close to “eire,” and sometimes Joyce used the two words interchangeably. The history of “eire” comes to Earwicker through the “ear,” hearing being the only sense not dormant in sleep. In one passage, Joyce writes, “…lift we our ears, eyes of the darkness…” That was Joyce’s command. It was Bute’s command, too.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other places including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.