The film carries the more readily because it is beautiful as a film. In its making, are neither has been subordinated to, nor has it been allowed to overrule science. The film has been felicitously designed in three parts, and those whose stomachs are weak—or those for whose vulnerability others fear—may see the first part if they are able to bear no more.

These are clearly human beings, like ourselves, entrapped in a terrible way of life in which the enemy cannot he annihilated, conquered, or absorbed, because an enemy is needed to provide the exchange of victims, whose only possible end is another victim. Men have involved themselves in many vicious circles, and kingdoms and empires have collapsed because they could find no way out but to fall before invaders who were not so trapped. Here, in the highlands of New Guinea, there has been no way out for thousands of years, only the careful tending of the gardens and the rearing of children to be slain. There is in Dead Birds enough of tenderness and sorrow so no man can doubt but that these people would welcome a political system that did not condemn them to an unceasing deadly engagement—to no purpose.

Dead Birds binds together the distant past, from which the ancestors of our civilization were able to escape, and the future toward which men—the same men, made of the same stuff, but hopefully possessed of very different cultural invention—are moving. But while Dead Birds binds together past, present, and future, the film also provides a savage paradigm of the fate that always waits, just around the corner, for men, because they are men who fight and organize for fighting and organize against fighting, not like other creatures, but as men.

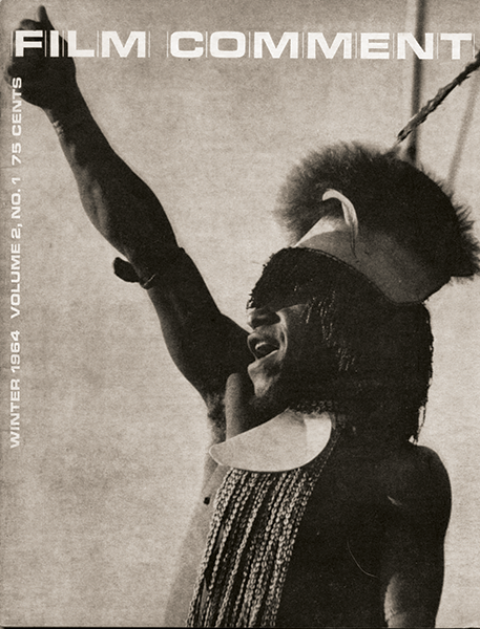

Dr. Mead, of New York’s Museum of Natural History, has lived in and written extensively of New Guinea, locale of Robert Gardner’s Dead Birds.