Make It Real: Acting Out

In William Shakespeare’s “all the world’s a stage” line from As You Like It, participants are famously characterized as “merely players,” subject to the garish banalities of life’s inevitable stages. But the metaphor (voiced by the character Jaques, to be fair to Willie) doesn’t hold for very long, not least because “players” are never merely so, for they are also occupationally equipped with the ability to consciously be and inhabit their roles. On stage or off, before the camera or behind it, there’s power in the play.

In Raed Andoni’s Ghost Hunting, former inmates of Jerusalem’s Al-Moskobiya interrogation center come together to construct a set and perform scripted scenes dramatizing their own experiences of torture, dehumanization, and isolation. The camera records these scenes, as well as more candid interactions among the men, with the same handheld observational approach. (Occasionally sequences featuring hatch-drawn animation and stylized lighting disrupt this continuity, functioning more like flourishes of subjective experience than demarcations between drama and documentary, à la The Act of Killing.) Andoni, a Palestinian filmmaker and fellow survivor, effectively serves as both movie and stage director, with the latter offered up for scrutiny by the former. “I’m the chief of the whole prison,” he says, sardonically pulling rank to silence two squabbling crew members. “I curse the day we built prisons.”

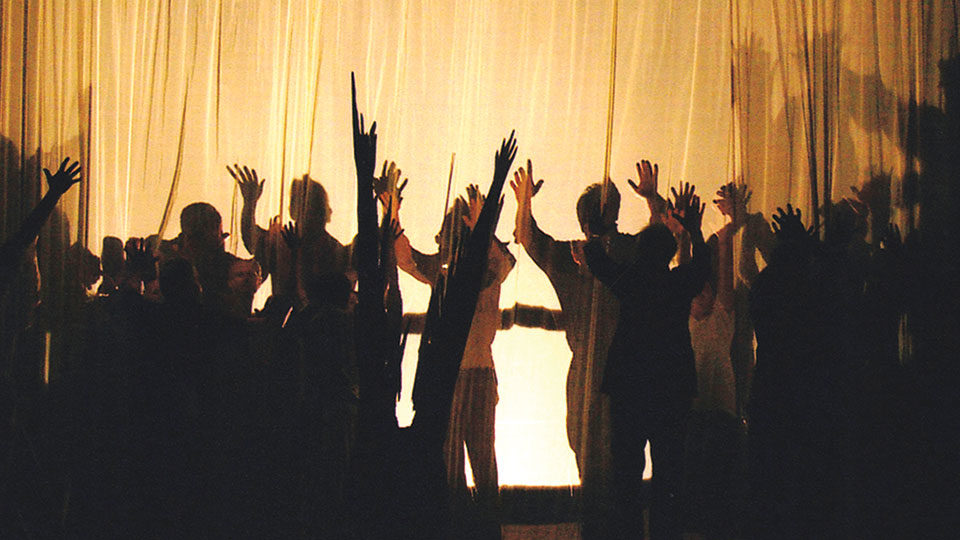

Such conflation of prison, stage, and film isn’t merely a clever device, deployed for metatextual disorientation. It’s based on an understanding that what these men endured was perversely, intensely theatrical—from spotlighted interrogations and heightened confrontations staged on either side of slotted cell doors to the playacting between guards and prisoners. Thus these auto-dramas of their traumas play less as experiments than extensions of lived experience. A similar attitude prevails in the far less traumatized community of Monticchiello, a small town in Italy that has written and performed new plays about itself for half a century. With Spettacolo, Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen trace Monticchiello’s latest story of itself from winter through summer, and from script to stage. “These things you perform in the piazza—is that really your reality?” a reporter asks in archival news footage. “Yes, of course it’s our reality,” an old woman says, leaning out a window. “It’s a way of living,” adds a man on the street. In these films, both presented at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest, performance isn’t an artificial notion introduced from without, but an honest unveiling of what boils up from within. In fact, theatricality is oftentimes less of an imposition than the artificiality of documentary film.

Spettacolo

When the players in Andoni’s film get caught up in the action, there’s seemingly little separating present-day dramatization from remembered experience. They push, cuff, berate, and strike one another. They intimidate one another. They break down. One man recalls having his bodily functions used against him, and moments later one such degradation is enacted for the camera. What distinguishes one from the other, of course, is that only now are they all agreeing to the terms, only now have they elected to pass back through the fire. But what happens for the camera is still live, is still an exposure to danger. It recalls a landmark of overlapped theater and documentary, Jonas Mekas’s The Brig (1964), in which the director filmed a complete performance of Kenneth H. Brown’s play set in a military prison as if it were the real thing. “The performance, by this time, was so precisely acted that it moved with the inevitability of life itself,” Mekas said. In that sense, it didn’t matter that everything was rehearsed, and though Mekas recorded within the safe space of Manhattan’s The Living Theatre, real bodies went through a real experience, and a camera watched it happen.

Andoni goes further in Ghost Hunting, enlisting not a theater troupe but former prisoners—found via a classified advertisement—to diagram the interrogation room, design their own cells, and alternate roles as prisoner and guard. Their expertise in such matters is beyond question; less certain, for some of the participants, are Andoni’s intentions. Recalling William Greaves in 1968’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, Andoni lets his collaborators voice doubts and cast aspersions, pushing him to the point of “controlled” physical aggression when the cast’s sole professional actor, Ramzi Maqdisi, accuses him of using others to exorcize his own demons. “You’re making this film because you’re trying to have a new experience in our skin,” he’s told. Andoni goes silent, his breathing changes. “Mind if I hit you?” Andoni asks. Greaves allowed his crew to question his abilities, whereas Andoni invites them to strip him bare. That the process hurts, and that there’s no real catharsis justifying the hurt or bracketing the process, doesn’t negate its value. Acting can be a method of understanding, whereas manufacturing resolution would be a betrayal of it.

This theater of trauma also calls to mind the therapeutic sessions witnessed in The Work, an overwhelmingly intimate new documentary by Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous. The film follows a four-day group-therapy retreat in Folsom Prison, an annual gathering in which outsiders can elect to join prisoners in the difficult work of self-reckoning, emotional exorcism, and rehabilitation. While not avowedly or intentionally dramatizing, the filmmakers don’t shy away from evoking the theatricality of the space, with globe lights suspended from above and multiple cameras visibly circling the huddles and scrums of men. Scrutinizing whether or not the unabated crescendo of anger, shame, regret, and throat-scraping screams is self-conscious, or self-dramatized for the space or the camera, is to disregard the essential theatricality of every space we enter, and how those dimensions inform everything we do together. Sometimes we harness it deliberately and for the better, and also sometimes a camera is there to capture and facilitate it. Entering into a charged, exclusive space—be it a four-day prison sojourn or a documentary film—nobody’s looking to be left unstirred. We talk of “playing to the camera” as if it were only a detriment, as if it can’t also be ennobling and emboldening.

Ghost Hunting

Although its subject is an act of overt auto-dramatization, Spettacolo is no less subtle about its complicity. Other filmmakers might have joined or commandeered the show, but as evidenced by their previous exploration of world-within-a-world auto-drama, Marwencol, Malmberg and Shellen are strenuously respectful of others’ art and lives. As the citizens of Monticchiello rehearse for a series of summer shows, the film focuses on the everyday performances of townspeople gathered to discuss what preoccupies and concerns them—continued unease in the wake of the global financial crisis yields a script that worries over the end of the world—seated together on a bench to gossip, eyeing tourists as they roll suitcases over sloped cobblestones, rolling the local pasta while wondering aloud if the custom will die with them. “Every night that led up to tonight—that’s what matters,” Andrea Cresti, longtime director of The Poor Theatre of Monticchiello, says before the public opening, and it’s a notion the filmmakers underscore by largely skipping over the finished product. We may yearn to see it, but the play is neither the subject nor (pace The Brig) the content of this film. The stage has its characters, its themes and metaphors, and so does the film. There’s bleed between the two, but they’re also different.

With his wild, white mane and evergreen weariness, Cresti plays the role of village artiste to a T. He’s constantly grinning and shrugging, claiming he doesn’t care, then strapping himself to the mast. At one point late in rehearsals, he’s seen sketching in a notebook and tuning out his young assistant—his subjective hearing cannily represented via plummeting sound levels when she speaks, and an inverted attention to pencil scratching against paper. It’s a dramatic flourish in both action and interpretation. And in an efficiently bravura sequence, the directors conspire with their players to form a thesis-embossing montage. One by one, we watch townspeople rehearse their lines. A cook reads aloud from the script while opening a can of tomatoes. A schoolteacher whispers in a doorway while children chatter in the distance. Two men stand in a clothing store—one orates while the other looks at the book to monitor his accuracy. “What problems could you have in a paradise like this?” a man repeats while driving through the Tuscan landscape. Another gets worked up from behind an office desk, addressing an empty room. And an older woman stands under a fruit tree, studying her lines while hanging clothes out to dry. For a few weeks every summer, the town plays itself in a theatrical setting. In Spettacolo, the town plays itself everywhere all year round. All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women truly players.

Closer Look: Spettacolo opens on September 6 and The Work opens on October 20.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and associate film curator at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.