Make It Real: Tell Me About It

At the Sundance Film Festival this past January, Robert Greene’s Kate Plays Christine took home a Grand Jury Prize for Writing—the first time a documentary had ever been recognized at the festival in that category. What does it mean to single out a documentary’s “writing”? Perhaps the Sundance nod was evidence of an advancing appreciation of nonfiction film as a construct; it might also have been a veiled, cheeky assertion that Greene’s film is not really a documentary. For even though Kate Plays Christine deliberately pushes the boundaries of nonfiction—Greene enlists actress Kate Lyn Sheil to play a character and to play herself playing the character—it's unclear what elements might be considered the product of writing.

Greene’s curious prize aside, the truth is that documentaries have long enlisted writing as an essential element of the form. Today, what’s meant by a writing credit can be unclear—sometimes it seems to acknowledge that a story has been crafted, at other times that editing is a form of editorializing—but its employ is not rare. In fact, it’s only in recent times that the idea of a written documentary could cause blanching. It was the postwar emergence of synch-sound that changed expectations for authenticity, fostering a notion that what’s spontaneously recorded in the moment isn’t just more real, but defines the discipline of documentary itself. It didn’t used to be thus, and neither, in practice, has it ever been. From early cinema on through the 1950s and continuing into today (if less prominently), documentaries have relied on words written on or read from a page. Those words can be functional and informative, or they can be as creative and crucial to the effect of a nonfiction film as picture, sound, or spontaneous action.

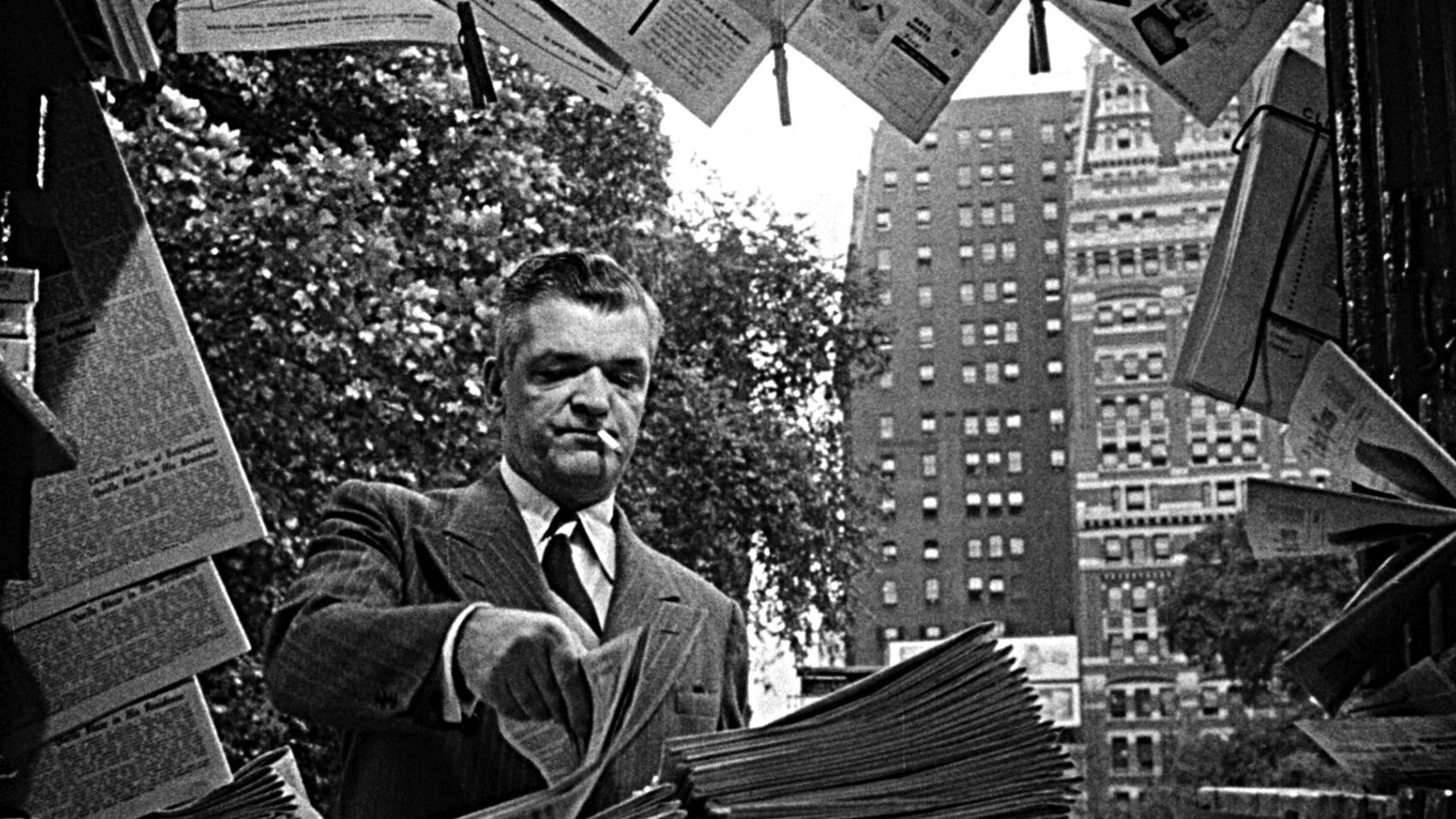

Released in 1948 and recently restored by Milestone Films, Strange Victory credits Saul Levitt as writer, and director Leo Hurwitz for “original screenplay.” Neither contribution defers to imagery or editing—language and literary construction are equal-status weapons in the arsenal of a film that also employs archival footage, crowdsourced clips shot by soldiers, photo-stylized original material, and reenactments in its buzzkill call-out of America’s hypocritical racism in the wake of its vanquishing of Nazism. The written material is crucial to the film’s greatness, though possibly at least partly responsible for its fading from view over the past 70 let-the-pictures-do-the-talking years. Levitt’s writing here is neither simply informational nor emotionally dispassionate. In its rhythms and diction, the text is variably plaintive, foreboding, confrontational, and withering. Phrases are repeated and modified, in a mode that nods to the poetic, but could more accurately be called the blues.

Strange Victory

“This was yesterday. This was how it was. Remember?” primary narrator Alfred Drake repeats over glimpses of horrifying activity on the front lines of World War II. “We paid. Everybody paid. Everybody. Everybody paid.” This is voiceover as auditory direct address, asking communal questions that can only hang ominously unanswered, and employing “we” not royally, but nationally. Levitt’s language is simultaneously focused and prophetic. “In the beginning is the word. The lie,” the VO continues, calling out racist preachers and politicians by riffing on Old Testament rhetoric. “Before the lie is to be believed there must be hopelessness. There must be hunger,” it continues, over ominously interpolated images of prewar Germany and postwar U.S., and provocatively couched from the perspective of a fabricating opportunist. “Add the necessary hate. Find an easy target and blame him for everything.” Cue shots of Jews being rounded up in Germany, and blacks being beaten and lynched in the U.S., which can also lead contemporary audiences to hear echoes of Trump- and Cruz-style Muslim-baiting. “In the beginning was the word,” Levitt writes. “In the end, rubble.”

Hurwitz associate Manfred Kirchheimer employs a ruefully poetic VO text for Claw: A Fable (68), which screened alongside the director’s Stations of the Elevated (81) in a belated theatrical release in 2014. The tactic was brazenly out of step with the same era’s observational-style touchstones Salesman (68) and Don’t Look Back (67), which privilege synch-sound immediacy over orated ADR. (And yet, to muddy historical assumptions: D.A. Pennebaker took a writing credit for the latter film.) Echoing Kirchheimer’s complexly gorgeous sorrow over the destruction of old New York—yet benefiting from a more ecumenical nonfiction era—Zhao Liang’s Behemoth (15) is both disturbed and enraptured by the strip-mine ravaging of the Chinese countryside.

In Zhao’s film, long-take sequences of labor and industry are bracketed by a rueful, mytho-poetic voiceover. Dante’s Divine Comedy is both source and inspiration for Zhao and co-screenwriter Sylvie Blum’s intermittent lyrical passages. Some critics found these episodes to be pretentious and “over-arty” distractions—seemingly a call for a straight observational presentation even as Zhao pointedly leads us away from such passivity. “The crew spends all night daubing on dusky makeup,” he says over portrait shots of laborers smudged with soot. “Whether they’re caked with powder or get a light touch-up, depends not on their mood, but on how fast the wind blows.” There’s pop poetry here, but also a tinkling of absurdist humor—“a light touch-up” is borderline profane in this context—that can’t help but destabilize the long-take, locked-off tripod austerity. The writing isn’t a nuisance to be sifted out—it’s a vital element in congress and conflict with an otherwise observational approach. There’s an in-kind unevenness to Patricio Guzmán’s formal gambits in The Pearl Button, which wanders between the director’s soft-spoken prose poetry and outward-facing interviews.

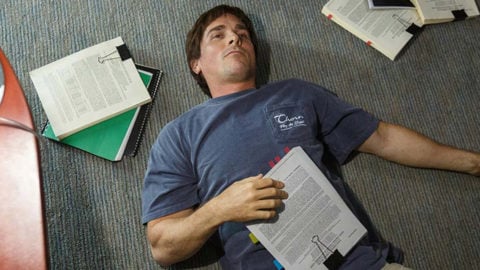

NUTS!

It’s become fashionable (and per Amy, Oscar-worthy) to construct stories entirely from archival material, without the aid of talking heads or scripted narration. Even as this trend incorporates masterful works such as Andrei Ujica’s The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu and Sergei Loznitsa’s The Event, this let’s-go-all-the-way mentality recalls the American stage musical’s collective turn toward full operatic scores (Les Misérables, etc.) in the 1980s, which implied that resorting to unsung passages of dramatic or comedic dialogue was somehow, suddenly, cheating. As often happens in these films, eschewing one narrative strategy increases dependence on another, and in the case of Amy, the reliance solely on available footage frustratingly defines the film’s and its protagonist’s arc—an arc that conveniently happens to be entirely, if ultimately questionably, visible to us.

By contrast, the whole design of Rithy Panh’s archive-based France Is Our Mother Country, which screened as part of MoMA’s Documentary Fortnight in March, is to reveal the violence and lies behind footage of French colonialists cavorting in Cambodia in the early 20th century. It achieves this via wry, latently furious intertitles that evoke cheery travelogues, allowing both content and genre to torpedo any notion that pictures alone could tell this story. “Our mother country offers freedom and knowledge,” reads one title, in advance of footage of Indochinese laborers who are not remotely free. Textual subterfuge is also in play in Penny Lane’s NUTS!, which took home an editing prize at Sundance for its deliberately unreliable deployment of dubious texts, misleading archival material, and “truthy” claims regarding the life and times of quack American doctor John Romulus Brinkley. Where Panh’s film apes the language of silent film intertitles, in NUTS! Lane and writer Thom Stylinski employ cheery narration that borders on museum tour-guide condescension, all the better to nudge us to distrust documentary conventions.

There’s no methodological hand-wringing at play in The Killing of America (81), presented as part of a recent True/False sidebar on Mondo cinema. Thoroughly out of place in the current nonfiction climate, Sheldon Renan’s documentary uses wall-to-wall narration over mostly archival footage to trace the viral spread of homicidal violence in American culture. Writers Chieko and Leonard Schrader offer up a chillingly clinical rundown of dozens of instances of assassinations, mass shootings, sniper attacks, and serial killings in the short window between the mid-1960s and early 1980s. Their “just the facts” text, delivered with colorless noirish punch by Chuck Riley, is punctuated by pithy biographical details and effectively overwhelmed by dates and statistics. The cumulative effect is harrowingly grim, which, of course, is precisely the point. The great artistry of The Killing of America is its seeming lack of it, as it hits you with the force of a blunt object that’s actually of intricate, intelligent, and morally vital design. Some subjects benefit from a hands-off, observational and reactive approach, and there’s much formal and aesthetic potential within that tendency. But with their pulpy, snuffy, unblinking movie missive, a work that has snowballed with relevance and urgency over time, Renan and the Schraders offer a reminder that not only is there no shame in deploying composed language in documentaries, sometimes it’s the most effective and expressive tool at hand.

IN FOCUS: Strange Victory plays at the Gene Siskel Film Center in Chicago May 20-23. NUTS! opens on June 22.

Eric Hynes is a freelance journalist and critic, and associate film curator at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.