Make It Real: No Place I’d Rather Be

What often qualifies films for consideration in annual best-of polls is whatever we’re currently calling a “theatrical release.” Some polls have even begun equating home streaming engagements with the actual movie theater kind. Film Comment offers an additional poll ranking films currently lacking U.S. distribution, but neither tally takes into account what are often the year’s most truly theatrical experiences: festival screenings.

These are events not defined by a distributor’s acquisition or the industry release calendar, and outside of major marketplaces like Sundance or Toronto, they’re distinguished less by duty than discovery. But just because no one’s asking us to rank these screenings doesn’t mean they didn’t happen.

For starters, few screenings had a greater effect on me than Stranger in Paradise at the Ragtag Cinema as part of March’s True/False Film Fest. Guido Hendrikx’s ingenious provocation challenges the viewer on a multiplicity of planes. After a fevered historical montage, the film takes place almost entirely within a nondescript classroom, beginning with a Nordic blond lecturer (Valentijn Dhaenens) callously explaining to apparent refugees why they’re not welcome in Europe, and why they need to return to their home countries. “We don’t want you here,” he says; cut to the astonished, largely non-white faces of those comprising his audience. Meanwhile within the Ragtag theater, pan over a sea of white, liberal-leaning Midwesterners with their mouths fully agape.

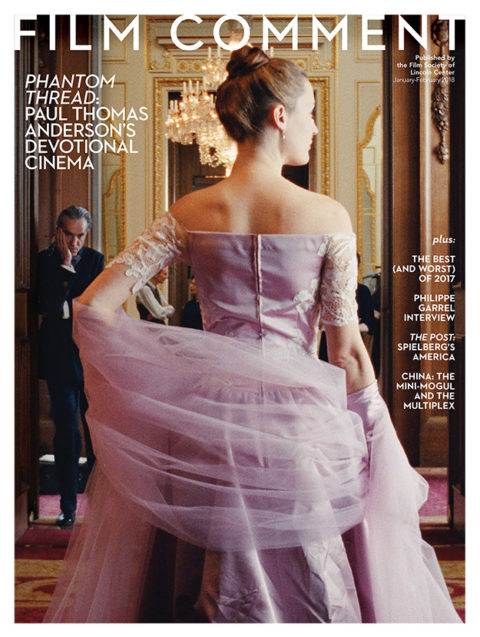

Taste of Cement

Hendrikx mercifully resets the scenario twice more with the same lecturer taking different tacks, first restoring oxygen to the room with a smiley-faced immigration-friendly presentation, then concluding with a wincingly pragmatic one, calling out which of the refugees in the room might stand a chance of sticking around. After a Kiarostami-like pseudo-observational coda in which a departing Dhaenens chats with local boys about the film they’ve been making, the lights went up on an audience utterly uncertain of what they’d just seen and what to make of it. Some questioned the apparent psychological distress of those featured in the film. I couldn’t help but wonder if the real distress being experienced wasn’t that of willing participants in at least a semi-staged endeavor, but rather of unsuspecting spectators being confronted by the multifariousness of their own privilege. And by a film cagey about its own formal borders to boot.

Narratives and experiences of exile and dislocation were expressed in festival films throughout the year, but two in particular stuck with me at the Camden International Film Festival last September. In Taste of Cement, viewed at the Farnsworth Art Museum in nearby Rockland, Maine, a group of Syrian men labor at a high-rise construction site in Beirut. By day, they work to rebuild a city after war; by night, as refugees they’re required to sleep in the catacombs of the building, haunted by visions and memories of a country currently being dismantled, to which they can only hope to have a chance of returning to rebuild in kind. That cyclical notion is manifested in the film’s structure, with highly aestheticized daylight construction footage giving way to raw, YouTube-grade visions glimpsed by the sleepless workers, which then repeats.

In visualizing this concept, Syrian director Ziad Kalthoum and Lebanese cinematographer Talal Khoury push past observational restraint and into something like ecstatic identification, expressing their subjects’ deep psychic dislocation as well as the absurd beauty of their instability, rising into sunlight every morning to look upon a landscape they’re allowed to construct, yet to which they’ll never belong. It’s that hypnotic tumbling—day rolling into night, beauty into terror, dreams into nightmares—that transformed me from a passive into an active (and ultimately enraptured) viewer.

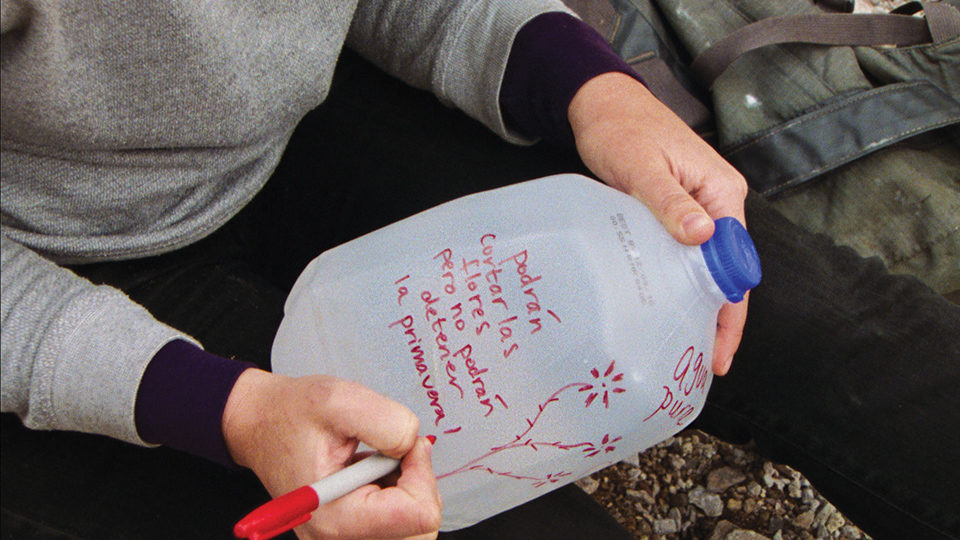

El mar la mar

Meanwhile across the street at the historic Strand Theater, J.P. Sniadecki and Joshua Bonnetta’s El mar la mar explored another terrifyingly beautiful landscape, that of the Sonoran Desert along the U.S./Mexico border. Their strategy for representing this zone of immense hardship and tragedy—where migrants looking for opportunities in the U.S. must traverse an inhospitable land with little food, water, or orientation—includes never showing those offering testimony. Instead, audio-only interviews are paired with stunning but studied 16mm footage of depopulated locations and abandoned objects. It’s a gambit destined to foster frustration in the viewer, but to purposeful and moral ends. What gives us a right to comfortably picture experiences we can’t actually share or fathom? Why shouldn’t we have to work to couple voice and visuals, testimony with lived experience? How better to exceed the limits of our understanding than by being confronted by them?

Later in the year at the Torino Film Festival in Northern Italy, Anna Marziano’s Beyond the One also experimented with asynchronous sound and picture. A handsome pastiche of various film formats and travelogue-like impressions is accompanied by an equally diverse chorus of people describing various approaches to romantic and sexual coupling. At first blush it’s just another metaphorical riff on disconnection, but once I got over this festivalgoers’ fatigue—one that’s rarely shared by less jaded members of the actual ticket-buying public—I was struck by the candor and conversational straightforwardness of Marziano’s interviewees. Not seeing them talk didn’t keep them at a distance, but rather invited me to populate and embroider her imagery with their ideas, and mine.

It was a far more complementary experience than the one I had earlier in the year at Sheffield Doc/Fest, where Ashley Sabin and David Redmon’s Do Donkeys Act? flummoxed me by matching gorgeous photography of furry beasts with purplish philosophical poetry read by Willem Dafoe. The combination proved so distracting, as if the Wooster Group had decided to read teen love letters over images of the divine, that I began to doubt whether it wasn’t intentional, a playful mismatch to (again) call attention to the limitations of both language and looking. The uncertainty itself made the screening memorable.

You Have No Idea How Much I Love You

That feeling of not knowing what you’re experiencing can be invaluable, especially when you’re in the hands of a filmmaker as deft as Pawel Lozinski, whose You Have No Idea How Much I Love You consists entirely of a young woman, a mother, and their therapist convening, confessing, and confronting each other in close-up. The film also screened at Sheffield, but I encountered it a few months earlier and 142 miles south at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, as part of the second annual Frames of Representation festival, which screens a single film per night. Such a format suits Lozinski’s project perfectly, as it’s both comprised of and built to engender reflection. A crucial piece of information is withheld until the film’s action has ceased, at which point you may or may not rethink everything you’ve just witnessed, or reevaluate everything you’ve just felt. It’s only in a venue such as the ICA, with Lozinski himself holding court, that the theaters of cinema, therapy, and the post-screening Q&A can overlap so provocatively.

And apparently it’s only in a place as far away as Melbourne, Australia, that I could discover a gem that could only have been forged in New York. Set entirely in Cecil Taylor’s Brooklyn apartment, The Silent Eye captures the American jazz legend improvising with a longtime collaborator, Japanese dancer Min Tanaka. Given that it memorializes an extended and inspired improvised exchange, the film would already be an essential document, but it winds up as far more thanks to Australian filmmaker Amiel Courtin-Wilson taking the cue to raise his own game. Blending a few days’ worth of sessions into one rolling, tireless exchange, and daring to add pockets of outside sound and instrumentation into the mix, Courtin-Wilson makes the film into a third creative element in the room. DP Germain McMicking veers close to both men, tracking not just movement for pretty pictures’ sake but their choices of when and how to move, where one leads and challenges the other, before spiraling out to ogle Taylor’s airy apartment and giant light-funneling windows. There are infinite points of entry, and also of exit—you could easily close your eyes to strictly listen for a spell and reenter welcomed and restored. Nary a word is spoken. Nary a “subject” is broached. It’s just two people making art with each other, witnessed by another small group of artists who made something else of it, presented to a hundred or so people in a small theater in Melbourne who really wanted to be there.

I have no idea what The Silent Eye qualifies for, what list to put it on, what market it might have. I just know I really liked being in those rooms—the one on screen and the one facing it—and have enjoyed drifting back to them ever since.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and associate film curator at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.