Make It Real: How It Happened

You wouldn’t know it from this season’s dispiritingly samey, well-heeled awards candidates. You wouldn’t know it from the thumbnail-friendly titles recommended by Netflix. You wouldn’t know it unless you were somehow able to see for yourself, either at film festivals, or at fleeting weeklong runs at the art house, or through targeted searches online, spurred by critical testimonials or social-media chatter. But the truth is that 2015 was another phenomenal year for nonfiction film.

For several years now, the most consistently adventurous, unpredictable, intelligent, and downright exciting films have been works of nonfiction. While narrative features have long operated within, or provocatively pushed against, established genres and aesthetic modes, the nonfiction form is in the midst of inventing new genres and modes, which are expanded, exploded, refined, and interrogated as they happen. (It’s telling that when narrative features attempt to break from formal expectations, they often do so by dipping into nonfiction.) These are days of artistic masterpieces, cris de coeur, impeccably crafted yarns, and purposefully irreconcilable experiments all working within the deceptively nondescript “documentary” catchall.

If there are any threads to the top nonfiction films of 2015—besides being excellent movies that I liked very much—it’s that each, in some way, did or showed things I’d never seen before. Each had the integrity to follow its own aesthetic, to assume its own shape. Each represents a work of art formed from the collision between filmmaker and subject, between an independent sensibility and the truth it identified. These aren’t repositories for realities simply found or captured—they’re movies that have been thoroughly and unapologetically made.

1. The Look of Silence (Joshua Oppenheimer) I suspect that 30 years from now we’ll still be talking about Oppenheimer’s Indonesian diptych, which improbably matches moral and historical rigor with formal and aesthetic vigor. Oppenheimer arguably exceeds the achievement of his queasy fever-dream epic, The Act of Killing, with an immaculate and mournful film in which every shot, cut, and sound cue has knee-buckling significance. Working predominantly with static interview-style scenes, Oppenheimer delivers a master class on how to mine drama, violence, and choked catharsis from potentially banal encounters, and furthermore how to leverage those encounters into breaking nearly 50 years of genocide-sanctioning silence. This is the year’s most vital work of cinema, of any kind.

2. In Jackson Heights (Frederick Wiseman) Just when you wonder if the 85-year-old master could possibly have anything left in the tank—especially since last year’s uncharacteristically (if subtly) autobiographical National Gallery felt like it could be a swan song—Wiseman comes forth with one of the best films of his 48-year career as director. Its vantage on this incomparably diverse Queens neighborhood is customarily clear-eyed, complex, and patient, but also quietly exhilarated. For native or longtime New Yorkers, its level of specificity can be overwhelming, stocked as it is with faces, locutions, storefronts, and especially sounds—the screech of the elevated subway, the ambient din of music and voices—that you never truly find on film. Anyone who rejects the cultural importance of immigration, or even the broad benefits of urban living, might want to consider In Jackson Heights a valentine to subtext.

3. Of Men and War (Laurent Bécue-Renard) The plague of PTSD among military veterans is one of America’s dirtiest secrets, a fact that French import Bécue-Renard addresses through neither an exposé nor a triumph-over-adversity human-interest tale, but rather through the radical act of listening. Camera and filmmaker are invited into group therapy sessions in which soldiers recount, at length, the traumas they have experienced; we then look on as the same men try to adjust to normal lives that may never feel normal again. Throughout, the idea is never to sum up, fix, or redeem the soldiers—which is neither possible nor necessary—but simply to bear witness to their struggle.

4. We Come as Friends (Hubert Sauper) An adventure tale that torpedoes the idea of adventure tales, and a work of great intelligence that eagerly reflects back its own ignorance, Sauper’s surrealistic, angrily poetic follow-up to Darwin’s Nightmare turns the Western liberal documentary on its head. Flying a self-made jalopy propeller plane, the filmmaker leapfrogs around Sudan in the days leading up to the formation of South Sudan, alighting not upon ignorant locals but savvy, knowledgeable citizens who are sick of being exploited and are understandably wary of Sauper. Where most films work hard to align themselves with their chosen heroes against a given enemy—the documentary “don’t worry, we get it” back-pat-selfie—We Come as Friends offers no such relief, for itself or the viewer.

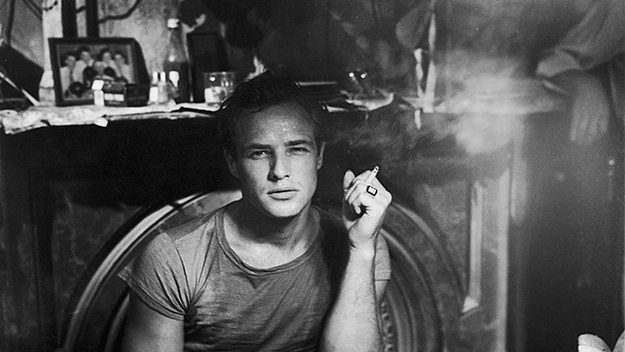

5. Listen to Me Marlon (Stevan Riley) From a ghostly, vintage digital rendering of the actor’s face, to an archival-sourced audio track spliced together to sell the illusion of narration from the grave, editor-director Riley has conceits to spare in the best Dead Celebrity documentary of the year (a very crowded, largely uninspiring field). The film honors the man without strictly serving him, instead parlaying elements of Brando’s life—the familial legacy of addiction and neglect, his uneasy relationship to performance—to explore surprisingly universal ideas of loneliness, regret, and the inexhaustible search for self.

6. Western (Bill & Turner Ross) Come for the novel concept of a nonfiction Western yarn; stay for the lo-fi beauty, dyed-in-the-wool empathy, and commitment to organic American community. The Ross Brothers’ third film is another portrait of place—the peaceable bordertowns of Eagle Pass, Texas, and Piedras Negras, Mexico—here sketched during a time of sudden change hastened by drug cartel violence. Few if any filmmakers working today can equal their ability to partner patient, long-form observational filmmaking with unabashed visual poetry—which seems less a strategy than an honest way of confronting the world.

7. Approaching the Elephant (Amanda Rose Wilder) This debut is a throwback in more ways than one. Its black-and-white photography and institutional setting—we follow a year in the life of an experimental, no-curriculum Free School in Newark, New Jersey—gives it the feel of a rediscovered Wiseman film from the Seventies. And Wilder’s deft, intuitive camerawork recalls that of Maysles or Leacock, magnetizing to the emotional center of scenes on the fly. What feels fresh is the film’s lack of overriding ideology, allowing for schoolroom sequences of both mortifying chaos and hard-fought harmony, and a general attraction to searchers actively trying, like Wilder, to figure things out.

8. The Iron Ministry (J.P. Sniadecki) From oscillating ceiling fans to hooks of bloody meat, steamy coach cars to climate-controlled First Class, everything’s fair game in this fragmented portrait of China from the inside of its trains. Thanks to Sniadecki’s snaking camera and Ernst Karel’s predictably ace sound design (the film begins with several minutes of avant-jazz-like rail screeching over a black screen), it’s a worthy addition to the Sensory Ethnography Lab’s deepening hard-rock catalog. But something else is also afoot here, evidenced by episodic conversations between the filmmaker and his fellow passengers. For Sniadecki, experiential cinema is also an interactive cinema. The train (and yes, nation) speeds along while everyone aboard—filmmaker and audience included—gropes around for orientation.

9. (T)ERROR (Lyric R. Cabral & David Felix Sutcliffe) People rarely come more conflicted than Saeed “Shariff” Torres, a former Black Panther revolutionary turned FBI informant turned rogue docu-exposé accomplice. There’s little precedent for the reportorial coup Cabral and Sutcliffe pulled off with this film—monitoring a misguided anti-terrorism sting from the inside—which is why American distributors treated it like a legal hot potato. But there’s also little precedent for what they offer in terms of narrative. For all of the shocking tactics employed by the state and the feds in this film, nothing was more rattling than a simple cut from one face, and one side of the story, to another.

10. Almost There (Dan Rybicky & Aaron Wickenden) Speaking of unexpected turns, it’s hard to keep track of how many times Rybicky and Wickenden change course while filming Peter Anton, an Indiana-based outsider artist they encounter drawing portraits of children at a street fair, and trail back to his appallingly uninhabitable home. Over eight winding years they don’t just follow him, they help him out of his condemned home, facilitate an exhibition of his artworks, and recoil from him when past sins come to light—and that’s truly only the half of it. Quickly, and thrillingly, the filmmakers give up on any standard story arc and instead let the mess—Anton’s and their interrelated own—be their guide.

And 10 more: Hotel 22, Guidelines, Democrats, The Pearl Button, Stray Dog, Heart of a Dog, Dreamcatcher, Field Niggas, Songs From the North, The Russian Woodpecker

Eric Hynes is a freelance journalist and critic, and associate film curator at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.