Majestic Images

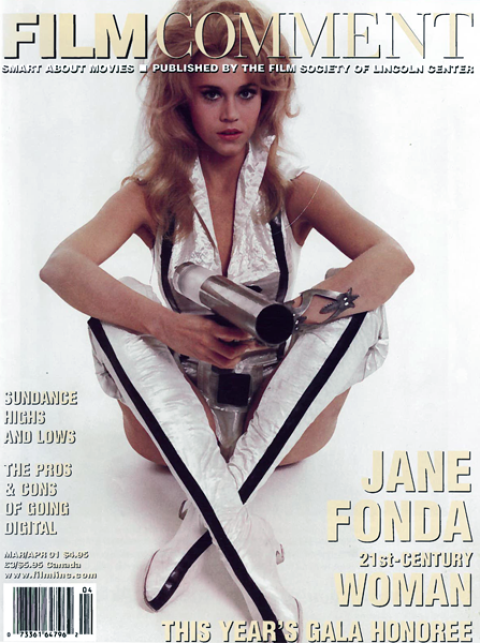

In 1999 the National Society of Film Critics cited Robert Beavers “for his contributions to the field of avant-garde film as exemplified by his 1999 program in the New York Film Festival as well as his ongoing work as a visionary film-maker and his activities in restoring and preserving the films of Gregory J. Markopoulos.” Such a public gesture of recognition was surprising and impressive: for Beavers is the maker of about 20 extraordinarily demanding, uncompromising, plotless films of often heart-stopping beauty. Furthermore, the program he had presented at the NYFF consisted of three films shot and first edited in the early Seventies, then reedited in the late Nineties: From the notebook of… , The Painting, and Work Done. It has been 25 years since the first and last of these films had been publicly exhibited in America, when the Museum of Modern Art invited Beavers to appear in their Cineprobe series in February 1974. A couple of weeks after the New York Film Festival, the Whitney Museum presented Beavers’ hour-long Ruskin at the start of the second phase of their “American Century” screenings. This sudden enthusiasm for a filmmaker working for 30 years was anything but a case of belated recognition. For decades he did not show his work in America. In fact, from the start of his career, Beavers carefully controlled the exhibition of his films: they still cannot be rented in any form; he supervises every screening. His unusual reservations about showing his films would seem to be one result of his unique sense of vocation.

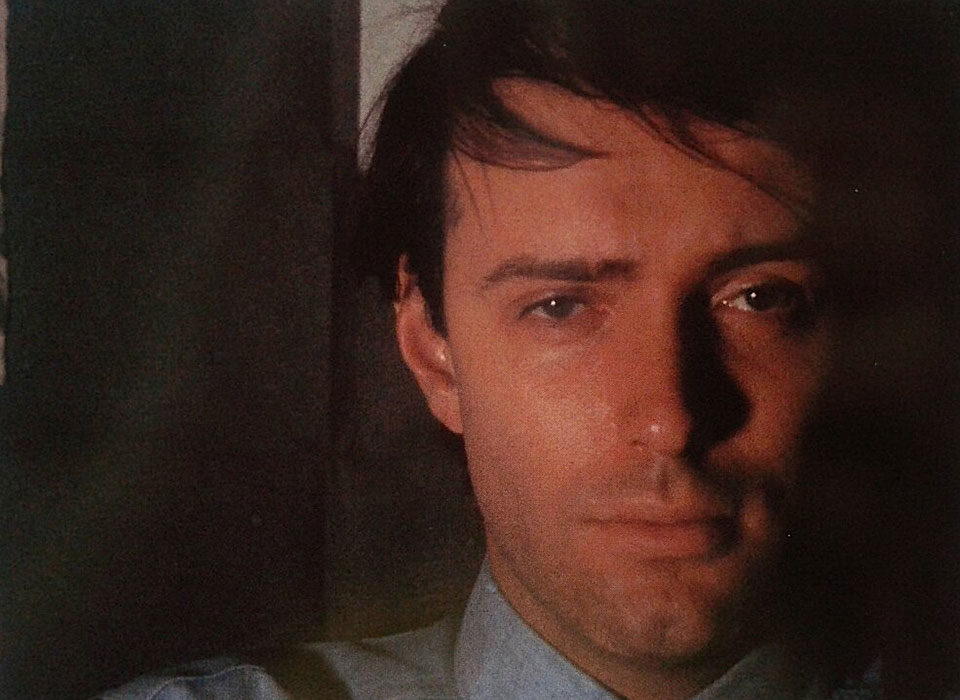

In his collected essays Circles of Confusion, the avant-garde filmmaker Hollis Frampton postulated four modes of composition for post-Symbolist art. One he called constriction: the reduction of a canon to a single author. His example was James Joyce: “the works from which he derived the laws that govern his writing were those of one author, Gustave Flaubert.” Surely this is a hyperbole, but an instructive one. A similar case in the history of American avant-garde cinema would be that of Beavers himself; a parallel hyperbole might usefully claim that he constricted the history of cinema to the films of Gregory Markopoulos, the Greek-American avant-garde filmmaker whom he met in 1965 and with whom he lived for the next 27 years, until Markopoulos’ death.

At 37, when Beavers met him, Markopoulos was at the height of his creative powers and artistic reputation. He was at an important juncture in his career and taught by example. At that time he was pushing his signature editing of single-frame clusters to its limits with The Illiac Passion (67) and returning to the in-camera editing of his precocious youth for sections of that film and especially for his portrait series, Galaxie (66), and the remarkable short tone poems Ming Green (66) and Bliss (67). He encouraged the 16-year-old Beavers to follow his route, abandon schooling, and begin making films right away, to learn the craft in the process of making his own works. Beavers’ apprenticeship began with watching Markopoulos shoot several of the portraits and in posing as the sole subject for the 45-minute film Eros O Basileus (67).

Galaxie

Markopoulos had favored mannerist compositions: intense colors, beautiful and elegant men with expressive postures and gestures; he directed Eros O Basileus in this way. He possessed an extraordinary confidence in the aesthetic infallibility of his intuitions. In turning to portraits of people and places in the late Sixties he put his faith more and more in the power of cinema to reveal the genius loci of the sites to which he was drawn, and the character of his sitters through the rhythms of in-camera compositions. At the start of his career many of Beavers’ fundamental attitudes toward his art were molded by Markopoulos’ tutelage. In the first place, he left Deerfield Academy, an elite prep school, convinced that a traditional university education would not enrich but perhaps detract, and certainly distract him, from his artistic vocation. Yet as an unusually determined, reserved, meticulous young man he was very far from the typical dropout of the Sixties. In his manner and his erudition he resembled the urbane, ivy- league educated poets of an earlier generation who chose to live in Europe—James Merrill, John Ashbery, Harry Matthews. When he and Markopoulos left America in 1967, the older filmmaker permanently withdrew all his films from distribution. Instead he conceived “the Temenos,” a visionary exhibition site in central Greece, where he hoped eventually to build a theater and archive, a pilgrimage site devoted solely to the cyclical screenings of his and Beavers’ films. Consequently, Beavers’ whole career has been focused on preparation for the eventual exhibition of his work at the Temenos.

From the beginning his films were built out of minimal events on which he concentrated attention to nuances of color, sound, editing, and, eventually, camera movement. In the whole of Beavers’ oeuvre there is hardly a single narrative passage; seldom do two events follow in a natural or causal timeline. One of his earliest films, Plan of Brussels (68), made when he was 19, has structures reminiscent of Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un poete, the fountainhead of lyric visions of the narcissistic imagination for Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, and Stan Brakhage as well as for Markopoulos. Shedding all traces of the narratives constructed by his predecessors, Beavers filmed himself in a hotel room, both at his work desk and lying naked on the bed, while in rapid rhythmic cutting, and sometimes in superimposition, the phantasmagoria of people he met in Brussels and images from the streets flood his mind. Fragments of Michel de Ghelderode’s play Duvelor can be heard on the soundtrack, cuing the viewer to the Faustian theme of this 28-minute film inspired by James Ensor’s paintings.

Beavers included geometrical shapes in iridescent colors among the fast alternation of images. As punctuation, lubrication, and percussion, these abstract elements shape and formalize the film. In his subsequent work similar structuring elements grow in importance. In Palinode (69) a disk-shaped matte continually shifting in and out of focus alternately blocks part of the image or contains it. Its respiratory rhythm matches operatic fragments of Wladimir Vogel’s Wagadu, as the camera studies a middle-aged male singer in Zurich, singing, eating, window shopping, meeting a young girl. The filmmaker told himself, “Don’t let yourself know what that film is about while you are making it.” Thirty years later it still remains astonishingly original and mysterious; elements suggestive of Fritz Lang’s M seem translated from criminal psychopathology to aestheticism.

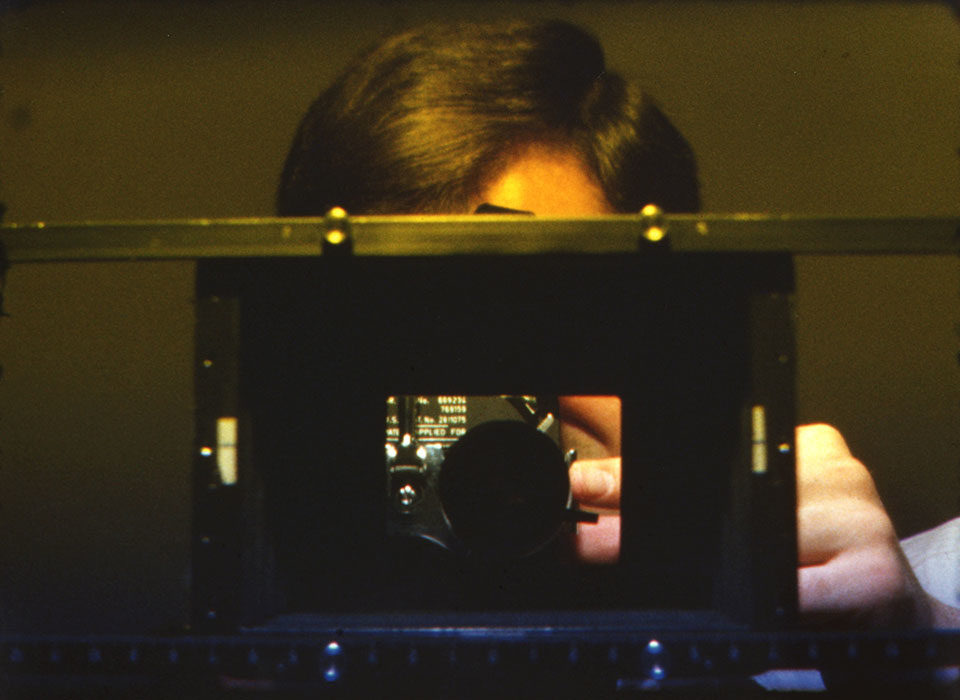

Diminished Frame

At the climax of Palinode Beavers shows his work space, his notes, and the apparatus he used to film the mattes. Two years later this will become the ground for the first film of his artistic maturity From the Notebook of … (71). A reading of Paul Valéry’s 1895 essay on the artistic imagination, “Introduction to the Method of Leonardo Da Vinci,” put the filmmaker on a path leading to the examination of the relationships between his ideas for films and the results of his practice. In the film he concentrates on his handwritten notes and on his matte box, exploring the ways in which color filters alter the light on the whole screen or parts of it. The alternation of filters and mattes gives the film its dominant rhythm, accented by abrupt camera movements, sweeping over sites in Florence mentioned in Leonardo’s notebooks.

All of Beavers’ films are distillations of the genius loci: he takes the measure of his life in Brussels, Bern, Zurich, Athens, Rome, and other cities, in the rhythms of his editing and the timbre of his images and sounds. This is most blatant in Diminished Frame (70), which he made in Berlin and into which he incorporated sounds of a Nazi rally that haunted his view of the city’s monuments. From the Notebook of… makes explicit how thoroughly the images of Florence have been mediated by the filmmaker’s readings, writings, materials, and craft. At the beginning of his essay, Valéry distinguished between “living” a biography and “constructing” one. The latter is supremely conscious when the subject is a creative artist, avoiding anecdote and incident, in order “to imagine the labor, and at the same time picture the accidental circumstances that may have engendered the works,” even though “the secret aim of a work is to make us imagine that it created itself.” In that sense, Florence is a construction of Beavers” film, at once the place in which he studied the powers of mattes and filters, the relationship of text to image, intention to execution, and the place represented through those filters and molded by those polarities. As such the film is a manifesto and a demonstration of the flexions of the filmmaker’s mind, instructive for viewing all of his films.

Beavers wrote in his text “La Terra Nuova,” reprinted in the Fall ‘98 Millenium Film Journal: “The act of filming should, in itself, be a source of thought and discovery.” And in “Editing and the Unseen”: “The many hours of patient editing, this listening to the image, waiting for it to speak and reveal its pattern; clear and often unexpected, yet recognized in its rightness…. I memorize the image and movement while holding the film original in hand; the memorizing gains weight and becomes the source of editing. To view the film projected on the editing table would only distract from this, creating the illusion that the editing is done in viewing.” Here we can hear Markopoulos’ intuitive self-confidence chastely refined into a principle of cinematic poetics: filmmaking requires attention to the acts of thought and discovery attending the conditions under which short strips of film are imprinted with colored light and images of places; and then, it demands concentrated and patient openness to new orders of assembly as the rhythms of the film pieces assert themselves in editing. In From the Notebook of …, for the first time, Beavers made this double process the center of a film. At 65 minutes it is the longest film of his career so far.

From the Notebook of …

The Painting (72), Work Done (72), and Ruskin (73-74) confirmed his authority as a filmmaker. In the first of these, he intercuts details from a Flemish triptych, The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus, which depicts a saint being drawn and quartered, with traffic patterns in a busy square in Bern; he intricately rhymes colors and vectors of tension until an image of Markopoulos and the torn pieces of a photo of himself anchor the metaphor in an allusion to a private conflict. (Beavers showed the film initially in a version without these revelatory final images.) Work Done projects the mental construction of Florence outside the filmmaker’s workroom. It fuses simple activities that impressed him in the city—bookbinding, frying blood, felling trees, paving a street with cobblestones—into a lyrical affirmation of the dignity and majesty of images, evoking in its careful depiction of artisanal labor the illuminated calendars of the Middle Ages.

The task of the middle cycle of Beavers’ career seems to have been to invent modes of mediation to curtail but not deny the subjectivity of the filmmaker’s imagery. At all points the images are objective and referential; yet he glazes their transparency by stressing a context of cultural artifacts. They are images touched by the filmmaker’s reading or viewing of historical art. In turn, they ask to be read in the same context. Ruskin visits the sites of John Ruskin’s work: London, the Alps and, above all, Venice, where the camera’s attention to masonry and the interaction of architecture and water mimics the author’s descriptive analysis of the “stones” of the city. The sound of pages turning and the image of a book, Ruskin’s Unto This Last (his widely influential work on the dignity of manual labor and craft), forcibly remind us that a poet’s perceptions, and in this case his political economy, are preserved and reawakened through acts of reading and writing. The extraordinary grace and beauty of the film, the polished perfection of its images, might deflect attention from its allegorical theme of the process of Becoming. In this allegory, a poet’s attention to the concrete particulars of water, stone, weather, and metropolis, mediated as images, can be recuperated both in Venice because it is an archaeological museum, and in the Alps insofar as weather patterns cyclically recur; in London, however, the traces of Ruskin’s city have been largely erased. Beavers’ self-representation as a reader/filmmaker, here unseen, links Ruskin to From the Notebook of…, thus bracketing the four films of the early Seventies that make up the second of three cycles of his work.

The third cycle, when it is completed, will consist of nine films—the longest of them a half hour—made since 1975. Two are not yet completed: one on themes from Borromini’s architecture, another on a painting of Il Sassetta. Sotiros Responds (75), Sotiros (Alone) (77), and Sotiros in the Elements (77), which have now been condensed into one film, began the series. Sotiros will be shown in the U.S. for the first time at the Walter Reade Theater in May. “Sotiros,” one of the Greek epithets for Apollo, means savior, redeemer, healer. Uncannily Beavers made the first of these films after visiting the temple of Apollo at Bassae, near to which Markopoulos selected a site for the Temenos, before he sustained serious injuries to his leg and to his vision when he and Markopoulos were hit by a bus. The second Sotiros film took Beavers’ convalescence in Graz as its theme.

Sotiros

The elliptical evocation of speech marks the first part of Sotiros, when the words “he said” recur rhythmically on the screen, as if some of the images were the direct discourse of an interlocutor, perhaps those of Greek village life that alternate with the details of a Swiss hotel room and an Austrian monastery. But this is merely a possible grounding of the words, which points to their very absence: the room resonates with the silent reverberations of what he said in them; the subject of the conversation is incidental to the primary force of (unheard) saying, until, in this viewer’s mind, the distinctions between saying and filming expand and collapse. Typically, Beavers will cut from a pan to a still landscape with an abrupt shock; sometimes he will hold a shot for a long time only to budge the camera just before cutting to another still image. He seems to be laying bare a syntax of image composition in which filmic frames, camera movements, and sounds take on new meaning by resisting the conventions of expression.

In a seminar at Princeton University Beavers spoke of the “philosophical majesty of the image.” His few short published texts do not so much illuminate his view of this as indicate the importance he gives to a dialectical approach to images grounded in poetics: “The spectator’s power of perception, liberated by this order of the senses and not by dramatic empathy, begins to learn what composes film and its harmonies…. I have emphasized harmony because one sees in film not just an image but the unity of image and its interval while simultaneously hearing the unity of sound and its interval.”

The title Beavers conceived for the three cycles that would constitute his collected films is My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure. If stretching out the hand points to the distance flying beyond visibility, it indicates as well the corporeal limitation of the man gesturing. Beavers repeats in exquisite variations an allegory of filmmaking: its measured rhythms turn us from the site of the filmmaker and point toward what cannot be made visible.

My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure

The films of Beavers’ third cycle dramatize the problematic status of the image by repeatedly interweaving gestures of signification—especially hand movements, allusions to storage vessels, and glimpses of shrubbery that has been shaped as topiary into a natural theater (in Salzburg). Having tacitly repudiated the mannerism and mythopoeia of Markopoulos’s cinema, Beavers divested his art of any appeal to a myth of originary experience and even to most references to extracinematic emotions. The consequent projection of mental movement, as the coming into being and testing of perceptions, associations, and ideas, invests his work with lucid serenity. Under his persistent gaze the polished isolation of solid things and simple acts gives way to the picturing of a restless mind, repeatedly attempting and succeeding as far as possible in defining the peculiar timbre of a place and finding the measure of his presence in it. The films themselves work so startlingly because the filmmaker has so subtly comprehended the structural impossibility of absolutely arriving at that definition. In Efpsychi (83) he may be acknowledging the deferred conclusive moment in this paradox by repeating the Greek word teleftia (“last things”) on the soundtrack.

Amor (80) is an exquisite lyric, shot in Rome (“Roma” reverses the letters of the title) and at the natural theater of Salzburg. The recurring sounds of cutting cloth, hands clapping, hammering, and tapping underline the associations of the montage of short camera movements, which bring together the making of a suit, the restoration of a building, and details of a figure, presumably Beavers himself, standing in the natural theater in a new suit, making a series of hand movements and gestures including clapping. A handsomely designed Italian banknote suggests the aesthetic economy of the film: the tailoring, trimming, and chiseling point to the editing of the film itself. The title Amor renders the Greek eros into Latin. Beavers had portrayed that divinity for Markopoulos in the film Eros O Basileus when they first met. Here the filmmaker declares his amor for the craft of filmmaking, for the sounds and surfaces around him, even on his body. The pastoral poem, Wingseed (84), returns to the scene of Eros O Basileus in its imagery: in rural Greece he filmed a naked young man amid goats.

Gregory Markopoulos died in 1992. The major work of his last 15 years was the reediting of his entire corpus for screenings in the Temenos; he restructured his work into the 22 cycles of Eniaios, a serial work comprised of approximately 100 films, which would take more than 80 hours to show. In the early Eighties he and Beavers had celebrated the founding of the Temenos with a series of outdoor screenings on the site. After spending much of his energy in the Nineties in fund-raising for the Temenos, Beavers intends to reintroduce that tradition in the next year or two. Like Markopoulos, he has also been reediting the picture, and more often the sound, of almost all of his works. What we have been seeing in New York, then, are revisions of films previously screened at a few European archives.

For Beavers “the philosophical majesty of the image” seems to imply a lifelong work of refinement. One film speaks to another, early to late, as the overarching work reveals itself to the filmmaker.