Louis Feuillade: Master of Melodrama

“Since you’re interested in the cinematograph, I am going to introduce you to the apotheosis of a forgotten genre. Soon it will be generally understood that there is nothing more realistic and at the same time more poetic than those serials that the intellectuals used to make fun of. It is in The Perils of Pauline, it is in Les Vampires that one must look for the great reality of this century—beyond fashion, beyond taste.” –Louis Aragon and André Breton, The Treasure of the Jesuits

It hardly seems possible—given the mechanically reproducible nature of film as a medium (and hence its mobility), the enormous popularity of his films in their time, and what now seems their indisputable greatness—that a director of the stature of Louis Feuillade could have disappeared from the history of the cinema so totally, and for so long. In France he was remembered as the director of Judex and a few other serials, but until the first Cinematheque Française revival of Fantômas in 1944, he was never considered a great figure of the French cinema.

In Great Britain he was completely unknown. His name appears neither in Roger Manvell’s Penguin Film nor in Paul Rotha’s The Film till Now. It was not until the National Film Theatre revival of Fantômas and especially Les Vampires in 1963 that any critics there had seen any of his films. The same is true in America: Louis Feuillade’s name does not appear in the New York Times Index to Film Reviews until a listing for 1965, when Les Vampires was screened at the New York Film Festival.

There are many reasons for this eclipse. First of all, Feuillade was a victim of his popularity: the enormous success of his films militated against his being taken seriously as an artist. Secondly, his career did suffer a decline after 1919, and in the six remaining years of his life he was never able to equal either the success or the genius of Les Vampires, Tih Minh, and Barrabas. Furthermore, the cinema was undergoing great changes during this period: by the early Twenties the French had discovered Griffith, whose mobile camerawork and dynamic montage—both absent from Feuillade’s films—became the touchstones for a new generation of critics.

The first French avant-garde movement looked upon Feuillade as precisely the sort of commercial filmmaker they were fighting against. Louis Delluc’s judgment was typical: “Judex and The New Mission of Judex are more serious crimes than those condemned by courts-martial.” André Antoine decreed that Feuillade “was certainly the man who has contributed the most to make those people with a spark of good sense and of reason disgusted with the cinema.” The only voices raised in defense of Feuillade during the Twenties were those of a few surrealist writers and the young Luis Buñuel, who once told Georges Sadoul how much he loathed the films of the “avant-garde movement” and all the techniques that were fashionable in the Twenties: rapid cutting, superimpositions, photographic effects. His models, he told Sadoul, were Fantômas and Les Vampires—direct translations of “une réalité insolite.” The irony, Sadoul tells us, was that, “like us all, he didn’t even know the name of the director of those films.”

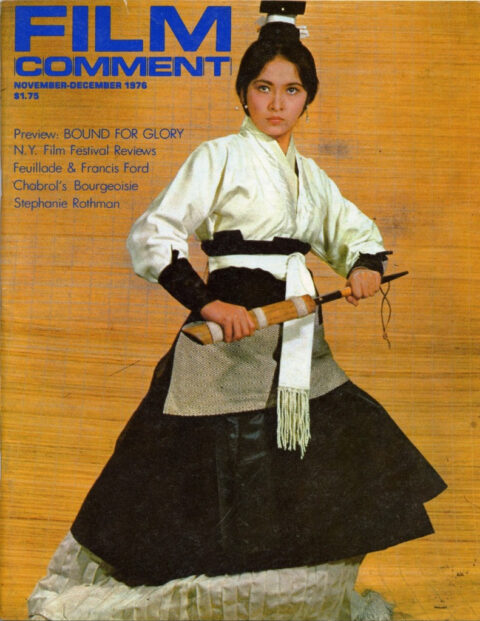

Stacia Naperkowska in a still from Les Vampires (1915)

The director of those films was born in 1873 in southern France, and grew up in a very religious family which insisted on his attending church-supported schools. Once he got his baccalaureate, he enlisted in a cavalry regiment without waiting to be called up for military service, and spent four years in the army. On leaving, he married, and followed his father and brothers into the wine trade. In his spare time he took part in amateur theatricals, and he was an aficionado of bullfights.

After the death of his parents, Feuillade decided to leave for Paris, where a friend got him a job in a newspaper office. His journalistic career ended in 1905 when a friend introduced him to the artistic director of Pathé, and he began to write scenarios. The Pathé connection didn’t work out, however, so Feuillade went directly to Gaumont where he was received by the legendary Alice Guy-Blaché. Originally Leon Gaumont’s secretary, she had become the first woman director in the history of the cinema, and by 1898 was the artistic director of Gaumont.

Guy-Blaché liked Feuillade’s scripts; one of them, Le coup de vent, was filmed by Etienne Arnaud in 1905. Two years later, she left Paris to follow her husband, who had just taken over Gaumont’s Berlin office, and she persuaded Gaumont to let Feuillade replace her. From 1907 he was in charge of hiring directors, buying scripts, and choosing stars; at the same time he was directing his own films. Historian Francis Lacassin tells us that Feuillade reckoned he had written at least 800 scripts, of which he had directed 700. Even when we consider that his earlier films were one- and two-reelers, Feuillade’s output remains impressive. (Gaumont still preserves the negatives of about 500 of these films. No one alive, I dare say, has seen them all.)

The early years, from 1905 to 1908, saw him turning out comedies. The historical series began in 1909, and the Film Esthetique in 1910, but he continued to make comedies—in particular the series devoted to Bebe, a child actor. Some of them are still quite funny, but Feuillade first became famous through his series of films under the high-sounding general title La Vie telle qu’ elle est (Life As It Is). This laudable effort at neo-realism, we are told, came about largely through the need “for economy: Pathé was Gaumont’s great competitor, and Feuillade always wanted to turn out better films more cheaply than Pathé could. When Gaumont told him that a Danish company (Nordisk) was making films for no more than 6.50 francs a meter negative costs, he declared that he could do it for only six francs a meter.

He did, and some of them are very good, although their plots have more to do with melodrama than with realism. One of the earliest and most beautiful is La tare (1911). The story is pure corn. A kind doctor gives a young woman attached to a wastrel a chance of redeeming herself through hard work in a provincial orphanage; but when her past catches up with her, she is dismissed from the orphanage, and considers suicide. In an extraordinary shot, Feuillade shows her in her attic room, with a bright shaft of light cutting the room in two; she then goes to the window, climbs on to the sill poised there ready to jump, her despairing face illuminated by the bright sunshine. She hesitates, and then falls back into the semi-dark room. And the film leaves her there, her head bowed in misery. In this early work one can already see that extraordinary combination of realistic treatment and melodramatic subject that was to be a hallmark of Feuillade’s oeuvre.

There is one tiny, tentative camera movement in the 900-meter film: a lateral pan (left to right, and back again) from the waiting room of an employment agency to the office. But Feuillade’s compositions were—and remained almost exclusively in depth. One could call it a theatrical point of view, if it were not that there has seldom been a director who could so stunningly escape theatrical perspective through the use of light and the movements of his characters.

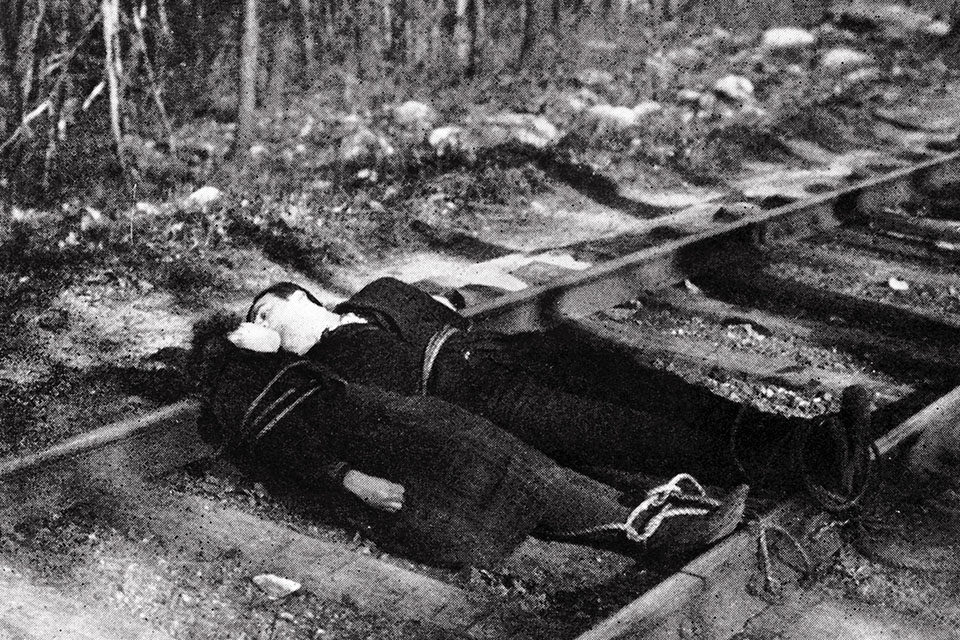

A still from Tih Minh (1919)

In the same year as La tare, 1911, Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre wrote the first installments of the story of the master criminal Fantômas. “In thirty-two volumes,” as Lacassin put it, “and in thirty-two months, they thrilled a whole generation.” And in 1913 Feuillade captured the imagination of the world with the first three parts of his five-part film Fantômas. The roots of Fantômas were both literary and political. The nineteenth century heralded the arrival, in Western Europe at least, of universal literacy. But when the illiterate learned to read, they did not want to read Racine or Corneille; so a whole new genre of literature appeared. At its grandest, it was Victor Hugo’s Les Misèrables and Notre Dame de Paris. But beneath the lyricism, melodrama was present. An even greater success was Eugene Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris. (When it is said that great literature was popular in its time, this only meant that it was popular with the ten percent of the population that actually knew how to read. These later authors—Hugo, Sue, and of course Dickens—were read by the masses.)

The Fantômas novels clearly belong to this tradition, but they were different in content. The earlier works were what was called “ improving”: by and large, the wicked were punished and the good triumphed—although often only on their deathbeds, or even after. Fantômas was the first anti-hero, the first evil hero. To be sure, he was opposed by a policeman, Juve, who stands for Good, but there was no doubt in any reader’s mind as to which was the more interesting character. Both the novel and the film of Fantômas are glorifications of evil, and one can only speculate as to the reasons why such a hero should appear in 1911 and why he should be so popular.

There is a connection, I think, with the exploits of the Bande à Bonnot and other anarchist gangs that were terrorizing and fascinating France at the time. The middle classes were terrified of these men, who indeed constituted a threat to authority and, even more, to property; at the same time, there was doubtless a thrill at the thought of the retribution which they perhaps felt they deserved. The reaction of the working classes must have been different: they had less to lose and therefore could simply enjoy the sight of the rich being terrorized. Whatever the reasons, both the books and the films captured the imagination of all France at a time when the anarchist gangs were at their most active.

I find the books almost unreadable today, whereas the film remains eminently viewable—for the obvious reason that Feuillade was a master of images and Allain and Souvestre were not great prose writers. However, I don’t think one can separate Feuillade’s visual style from his material: if you like the one, you’ve got to take the other. This was not true with early films like La tare. But it is the sudden introduction of Evil in Feuillade’s work that provided the stimulus for his talent. All his best films—Fantômas, Les Vampires, Tih Minh, Barrabas—are involved with it. Whenever he tried to be moralistic, the films lost much of their force. The reason for this lies in the tensions set up in Feuillade between his consciously held views (we know he was both a Catholic and a monarchist) and the fascination for him to be found in men like Fantômas and women like the enigmatically anagrammatic “vampire” Irma Vep.

Obviously, Feuillade could not consciously either approve of or identify with a master-thief like Fantômas; and yet the film can only be seen as a celebration of this evil figure—this omnipotent, ubiquitous master of disguise. Whenever Fantômas appears to us in action, he is covered from head to toe in black tights and a Klan-style slitted hood over his face. This is his disguise; it is also Feuillade’s own disguise. And in the film’s most famous shot, when Fantômas is seen as he blows up a house, it is with both arms raised in triumph, silhouetted against the smoke from the apocalyptic explosion.

What makes the film so believable is the fact that it is shot in real exteriors. As Annette Michelson aptly remarked about Les Vampires, Fantômas, which is all about dis-location, is all shot on location: “Haussmann’s pre-1914 Paris, the city of massive stone structures, of quiet avenues and squares, is suddenly revealed as everywhere dangerous, the scene and subject of secret designs. The trap door, secret compartment, false tunnel, false bottom, false ceiling, form an architectural complex with the architectural structure of a middle-class culture. The perpetually recurring ritual of identification and self-justification is the presentation of the visiting card; it is, as well, the signal, the formal prelude to the fateful encounter, the swindle, hold-up, abduction or murder.”

This constant interplay between reassuring everyday appearance and the frightening realities which lie just below is the key to the fascination of Feuillade’s best work. The great sequence in Fantômas—the shoot-out on the Quai de Bercy, with Juve and Fantômas darting between the huge wine barrels—is not merely picturesque; somehow these barrels take on as much importance as the protagonists. Indeed, from the way in which they are shot, they become as mysteriously threatening as some of Magritte’s renderings of ordinary objects. And Feuillade’s composition in depth helps, because it is in its many levels that he can best orchestrate the many levels of significance, disguise, treachery.

A still from Fantômas (1913)

Les Vampires (1915-16) is a greater work than Fantômas because it was written by Feuillade as he went along, and thus conceived entirely in cinematic terms. But there is another reason: the presence of a female character, Irma Vep (Musidora). In the first sequence of the film, a painting of a sphinx is pushed back from the wall of an apartment to reveal, in the hole cut behind it, the black-tighted Irma Vep—and suddenly we realize that the battle is going to be not only political or social, but also sexual.

Once again the subject of the film is a gang of jewel-thieves. The nominal hero is not a policeman, as in Fantômas, but a more ambiguous representative of law and order: a journalist who is determined to capture the gang. It soon becomes clear that this gang of jewel thieves is being pursued by Philippe Guérande with somewhat mixed motives. It is important that they are jewel thieves, that they prey only on the rich. And their method is not haphazard: they have organized a plot against constituted society; they are a potential revolutionary force, an underworld which is rising up to take over the “real” world.

Whether Feuillade totally understood all this is unlikely. But his audiences did: a great wave of protest arose against what was termed his glamorization of crime. The fact that the gang was ultimately vanquished by the police did not deceive anyone. They knew it was only a gesture of the mildest self-censorship. on Feuillade’s part. Significantly, the high priestess of the Vampires is killed neither by the police nor by Guérande. It is the reporter’s wife who guns her down, and the hero who lingers longingly over her dead body in a vivid expression of the sexual attraction exercised by this dominating woman. The image may also be an unconscious recognition of a society in love with its own destruction. When a large party of rich people is gassed by the Vampires, the gas is sweet smelling, and the guests first think it must be some new brand of incense or perfume. And in the penultimate scenes of the film—when the vampires think they have triumphed—Feuillade films their celebration, their witches’ Sabbath, with an enthusiasm and conviction that underlines his ambivalence.

Seeing Les Vampires today is quite a different experience from what it would have been seeing it at the time. Now it is shown in one go: six one-hour episodes strung together, rather than six episodes seen at varying intervals. (Imagine watching three weeks of Mary Hartman at a single sitting!) Furthermore, the intertitles for this film have long ago vanished. We are obliged to figure out the action without any help—except, that is, for Feuillade’s narrative genius, which is more than adequate to an understanding of the film, without our reading the letters to which the characters react with horror and amazement. With the titles missing, the film goes much faster, and this is all to the good since present-day audiences are more sophisticated as to film narrative than audiences of 1915. There’s yet another appeal the film has for us today: the mystery and charm it records of a Paris long since gone—all the urban poetry of deserted streets, terrains vagues, buildings left half-finished.

Contemporary audiences got something else from Feuillade’s films: the thrill of seeing all these extraordinary and terrifying things happening in the streets they knew, that they walked down every day. For them (and in some measure for us, too) there was a conjugation of a naturalistic rendering of Paris with the evocation of strange and frightening happenings. Hitchcock perfected the notion, but Feuillade discovered it: that nothing can be more frightening than extraordinary events against an everyday background. In a perfectly ordinary room, a bishop presses a button, and a cannon comes out of the fireplace, all set to destroy a nightclub next door. Before the cannon is fired, however, the curtains of the window are first carefully pulled, and the window is opened. After the cannon goes off, the window is closed and, methodically, the curtains are drawn.

Alain Resnais: “People say there is a Méliès tradition in the cinema, and a Lumiere tradition. I believe there is also a Feuillade current, one which marvelously links the fantastic side of Méliès with the realism of Lumiere, a current which creates mystery and evokes dreams by the use of the most banal elements of daily life.” The surrealistic method, in fact—the method of a Magritte.

Musidora appearing in Feuillade's Les Vampires (1915)

If Les Vampires was the greatest of Feuillade’s films, there were two others, almost as good, to follow. But not immediately. The fact that one of the episodes of Les Vampires had been temporarily banned by the chief of police was enough to frighten Feuillade and Gaumont. So the successor to Les Vampires was very carefully worked on to avoid offense. Judex (1916) was the result, and it turned out to be Feuillade’s most popular film—perhaps because of its enlightening moral tone, but also because of its star, René Cresté. As historians Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach so neatly put it: “Cresté’s cape: that was Judex … that majestic cape that he threw back over his shoulder in such a noble gesture. The rest was of little importance: the kidnapped girls, the highwaymen …. There was nothing in Judex that was not already in The Exploits of Elaine, The Perils of Pauline, and even more in Fantômas. But there was that cape. Because of that cape, because of that fatal beauty, that smile, every young person in France dreamed of Judex.” Seen today, Judex does founder in its self-imposed sentimental morality. And The New Mission of Judex (1917) is almost unwatchable; Louis Delluc’s strictures on Feuillade are justified by this film.

But Feuillade had not completely gone over to respectability. For the two Judex films were almost immediately followed by two serial-films which almost equal (and some believe even surpass) Les Vampires: Tih Minh (1918) and Barrabas (1919). Tih Minh, as Francis Lacassin put it, “leaves the gray streets of Paris for the Riviera, where the bright Mediterranean sun seems to efface the differences between good and evil. The Vampire gang are now bent on world conquest: the film is about their revenge for the death of Irma Vep, and their victim is Tih Minh, a beautiful Oriental maiden. Scenes like the fight on the roof of the Hotel Negresco possess that dreamlike evil magnificence which no one was ever able to achieve so completely as Louis Feuillade.”

True, Tih Minh has an “improving” end: crime is punished, virtue has its reward. But not all the criminals are killed. Dolores de Santa Fe is taken alive, and the good doctor Clauzel brings her back to Paris to undertake the difficult mission of converting this adventuress and to deliver her from the evil spirits. In a final twist, she outsmarts him: somehow she had managed to procure poison from the wicked Asiatic doctor Kistna, and she escapes conversion—through death.

Barrabas is the last of the great series. In many ways it is the best—except for its rather slow beginning. The plot of the film is so complex that it necessitated a great deal of exposition, in fact almost two hours of it. There are so many things we have to learn to register, so that when Feuillade springs his trap, bottomless chasms can metaphorically open beneath the feet of his characters. But once the trap opens (and it is actually the fall of a guillotine blade that sets the infernal machine working), the pace never slackens. Barrabas, too, was largely shot on the Riviera, in the hills overlooking Nice, and it achieved an even greater plastic beauty than Tih Minh. It was also more cosmic. The aim of the criminals in Tih Minh was “God strike England”; in Barrabas, it is the whole world they are after. Indeed, the Biblical resonance of the film’s title seems to suggest the continuing and eternal existence of an underworld, of the forces of evil.

Had Feuillade’s career ended with Barrabas, his reputation might have had a greater chance of survival. Unfortunately his later films did little to enhance enhance his reputation. Vendémaire (made in 1918, between Tih Minh and Barrabas) prefigures his decline. Photographically, it is extremely beautiful, particularly the opening scenes of refugees from the north descending the Rhône river by ship. But the patriotic plot (German soldiers disguised as Belgians) is not terribly interesting, and already there are signs of the series of tear-jerkers that Feuillade was to make from 1919 until his death in 1925.

An undated portrait of Louis Feuillade

Feuillade did have an influence on the history of the cinema—but it was a long-delayed one. Except in the work of Buñuel who, as we have seen, admired his work (and in L’age d’or and some of his other films continued the Feuillade vision of the extraordinary filmed as if it were the most ordinary thing imaginable), we can find few traces of Feuillade until the late Forties, in the surreal documentaries of Georges Franju and Alain Resnais. “Of course,” Resnais has said, “I haven’t sought systematically to imitate Feuillade. If you try to do it that way, it doesn’t work.” (And this, I think, is the reason why Franju’s Judex is much less authentically Feuilladesque than his Les yeux sans visage.)

The line continues on to the films of Jacques Rivette—particularly Out One: Spectre, where the shots on the Place d’Italie surely must have been inspired by visions of Feuillade. And some of the Montmartre locations in Celine and Julie are reminiscent of Feuillade’s use of Montmartre in Les Vampires. If Rivette’s original idea for Out One had ever been carried out, we might even have had a great television serial. This film was designed as a series of thirteen one-hour films—which takes us straight back to Feuillade. But the past, as Resnais noted, can never be recaptured directly. Those who have seen the thirteen-hour Out One say that, fascinating though it is, it is inferior to Out One: Spectre, the four-and-a-half hour condensation—and transformation—of the original footage.

It’s said that “No voice is wholly lost,” and—despite the inaccessibility of most of his work—Feuillade the commercial craftsman, Feuillade the fabricator of films, still lives. “Please believe me,” he wrote, “when I tell you that it’s not the experimenters who will finally obtain for film its rightful recognition, but rather the makers of melodramas—and I count myself among the most devoted of their number … I believe I come closer to the truth than they do.” And, looking back, we can find only one answer to the question of whose films came closer to the truth: Delluc’s or Feuillade’s. The maker of melodrama may not have outlived his critics. But his films have.

This essay is a shortened version of an article from A Critical Dictionary of the Cinema: The Major Filmmakers to be published by The Viking Press (U.S.) and Seeker & Warburg (U.K.).