Lone Wolves at the Door of History

I’ve never felt bad about missing out on the excitement of “discovering” a new, hitherto-untouched-by-western-eyes cinema, mostly because the danger of inflationary rhetoric and overspecialization is mighty high. Not that this has been the case with Central Asia. There is a wonderful camaraderie among filmmakers and their assorted champions, and the level of territorial wrangling is nothing compared to the titanic feuds and grudges between the Pacific Rim specialists.

Which raises the question: how is it that these glorious films, spread across roughly 40 years and five countries, with bursts of activity coming at different intervals, have never excited the land-rush mentality that took hold of us westerners when we got our first glimpse of product from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Iran? Perhaps it’s because the great films from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tadjikistan are made by loners, more modest than a Hou or a Kiarostami. To be clear: it’s not the films that are modest, but rather the sensibilities that shape them. Such modesty seems to float through the air breathed by an Okeev, an Omirbaev, a Narliev, or even an extroverted stylist like Ali Khamraev. There’s an inherent distrust of grand statements—it’s impossible to imagine any of these filmmakers doing something as grandiose as the affirmation of life in The Wind Will Carry Us or the past/present fusion near the end of . Not to imply a judgment on anyone, but I think that these directors might be even more deeply caught up in a love of cinema per se than their peers in more economically robust countries. The Central Asian filmmakers have learned to distrust neither the power nor the value of art.

Despite its proximity to where the action is right now, Central Asia remains one of those corners of the world by which the west has never exactly been transfixed. We tend to be interested in a given country only to the degree that it affects our own interests (remember last year’s quickly evaporating fascination with Afghanistan). I’m not counting such purely mercenary phenomena as the steady stream of businessmen arriving in Kazakhstan in search of oil, or Uzbekistan’s military base potential. The fact is that the films made in the five former Soviet Asian republics, sometimes known as “Central Asia and Kazakhstan,” have never broken out of the festival circuit. Cultural remoteness aside, there are many reasons for this state of affairs: dissemination problems (initially caused by the Soviet Union, then by its sudden absence), a lack of artistic flamboyance, a heavy reliance on outside sources for funding, a dearth of any local film scene whatsoever (unlike, say, movie-mad Iran), and an overall immersion in a culture, or series of cultures, of which we westerners have absolutely no grasp. We can’t get our minds around these countries that are sort of Russian, sort of Middle Eastern, and sort of Asian. They know all about George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, but we know absolutely nothing of Manass, Ulugbek, and Timur the Great. Our colonialist hangover afflicts politics, business, and the arts as well. It even afflicts the very language we use. The unspoken rule is that a region is worthy of recognition only in proportion to the amount of muscle it’s flexed, or how easily it can be defined or packaged. If this seems like a stretch, then read Peter Bart in a recent Variety on all the suckers out there who traipse off to far-flung film festivals like Ouagadougou—unbelievably, Bart tried to milk the name itself for laughs. The Central Asian films resist easy categorizations, both cultural and cinematic. The best of them are stubbornly handcrafted and quietly local. It may seem like an easy generalization, but the films made during the Soviet era tend to cleave to regional history and cultural identity, while the post-Soviet films articulate that odd quality that Jim Hoberman nailed in the subtitle to his underrated book, Red Atlantis—“communist culture in the absence of communism.”

Let’s call it a cinema of collective solitude.

The Road

This January, I found myself in Central Asia with a colleague, Russian film programmer Alla Verlotsky. We went there to see films and meet filmmakers, in preparation for a retrospective of work from the region. In the past decade I’d fallen in love with the films of Kazakhstan’s Darezhan Omirbaev, whose work—Kairat, Cardiogram, and, most recently, The Road has received the most significant international exposure. Ardak Amirkulov’s delirious historical epic The Fall of Otrar (90) astonished me at the 1997 San Francisco Film Festival, and that led to the contact with Alla. She opened my eyes to the astonishing riches tucked away in the five regions, made by names hitherto dropping exclusively from the lips of European festival-goers and the most dedicated critics and fans: the Kirghiz Tolomush Okeev, an “outdoor” filmmaker to rival Malick, but earthier and less cosmically minded, more grounded in the mountainous landscape where he spent his youth; the Uzbek Ali Khamraev, far and away the most flamboyant director in the entire region and an artist of rock-solid humanism and amazing expressive power (his 1975 medieval pocket epic Man Follows Birds merits comparison with Paradjanov, but it has a more boyishly melodramatic undertone); the other Kazakh masters Amir Karakulov, Serik Aprimov, and the man who more or less inaugurated the Kazakh New Wave, the supremely elegant storyteller extraordinaire, Ermek Shinarbaev.

The buildup to this trip was odd. When I talked it over with family and friends, there was a mixture of envy and puzzlement. As in: wow, how great to travel to such faraway places, but why those faraway places now? “You’re very brave to come here,” said Yusuf Razikov, our host in Uzbekistan and the director of Uzbek Film Studios, as well as a sharp, sardonic filmmaker in his own right. I didn’t share his opinion, but since part of the American self-image is that everyone should be coming to us, it’s easy to understand.

Since I knew the region only through its films, mental comparisons between the landscapes we were walking or driving through and the images I’d seen came fast and furious. It seemed poetically right that we should land in Almaty at 3 a.m. in a fog, and my first impression reminded me of another film from an artist not even remotely connected with the region. People milling in the darkness and fog and wood smoke, cab drivers waiting for a fare, men waiting to haul baggage, people waiting to be picked up, or just waiting. In straggling groups of two or three at most, or often alone, shuffling back and forth, hands in pockets. It was impossible to not recall Chantal Akerman’s 1993 travelogue D’Est, shot in Eastern bloc countries after the fall of the wall. Akerman was really on to something there, with those mesmerizing tracking moves past waiting people—this was a constant throughout my brief travels in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Perhaps only a filmmaker from outside could make something so substantial and revelatory out of such apparently insignificant activity. Another film that often came to mind was Alexei German’s Khrustalyov, My Car!, with its refrain of lone individuals wandering through monumental, dilapidated buildings. More appropriate, since German was not only the co-author of The Fall of Otrar’s screenplay but an instructor at Vgik, the film school in Moscow where most of the Kazakh filmmakers studied. All the way through our quick three-country tour, I had a strange sense of cinematic déjà vu: the images and sensations from the films were blending into the ones I was forming during our travels, of the mountains and steppes and snowscapes, the May-Day-parade-sized boulevards and grandiose buildings in the cities, the lonesome little eateries, the faces, the colors (somber Kazakhstan, warm Kyrgyzstan, blazing Uzbekistan), the gestures, the overall zeitgeist (lonely Kazakhstan, warm Kyrgyzstan, conflicted Uzbekistan). The more I saw, the more I was touched by these filmmakers committed to defining a sense of cultural identity without an ounce of nationalism, at this strange crossroads between the communist past and the free-market present, between Asia and the Middle East, between a faith-driven society (Muslim, in this case) and a secular one.

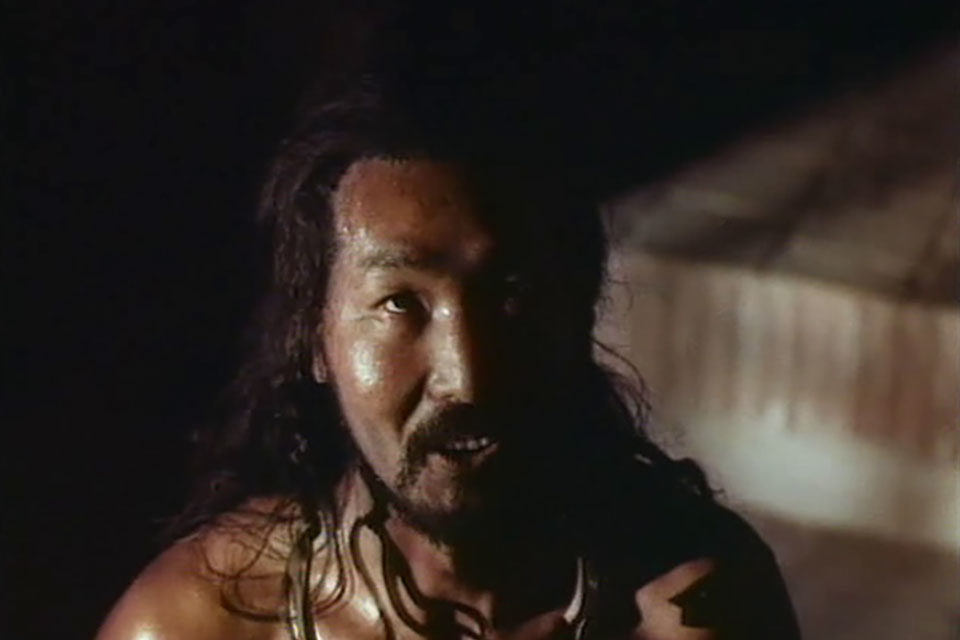

The Fall of Otrar

The many and various parallels and divides between films, filmmakers, and regions are fascinating, instructive. Kazakhstan, which boasts a land mass greater than Europe’s, is the youngest of the five countries, a national construct only a little over 100 years old. I kept hearing that this was a nation of loners with no sense of history, a despairing diagnosis delivered in optimistic tones. The charismatic Serik Aprimov, with his infectious giggle, gave me the most poetic description. He told us that “Kazakh” means “the people who wandered away from the center.” I checked this out with a few other people, and after a knowing laugh most of them grudgingly agreed that even if it was not absolute fact, the sentiment was right.

This loner mystique accounts for the singular devotion of Kazakh filmmakers to rendering the textures of anomie and disquiet on the screen. Serik Aprimov’s The Last Stop (89), a landmark in the valiant heyday of the Kazakh New Wave, hones in on activities and states of mind that most filmmakers don’t bother with: what it’s like to sit around with your friends and kill time on a Saturday afternoon, the feeling of being outside at the end of a nothing day, right around sunset (photographed with patient exactitude by Murat Nugmanov, a secret hero of Kazakh cinema), the slow buildup to violence in a town where there’s too much alcohol and not enough to do. Amir Karakulov covers similar territory in Last Holiday (97), about a group of delinquents on a downward spiral during the May holidays of 1979, but from more of a distance. Where Last Stop has a raw, present-tense immediacy, Karakulov’s compact masterpiece is sadly elegant, a tragedy of lost adolescents viewed from a calm remove. (Karakulov’s underrated new film Jylama [03], shot on DV and improvised with non-actors in a rural setting, is rougher but similarly hypnotic in its concentration on simple actions in their full measure of time.) Omirbaev also deals with anomie but nails it from the inside, using the most precise cinematic language since Hitchcock and Bresson (both names came up when we talked) to illuminate the mental landscape of his troubled heroes. The young man from the steppe in Kairat (92), the family man forced to commit murder in order to pay back his debt in Killer (98), the dissatisfied filmmaker in 2001’s The Road (played by Tadjik director Djamshed Usmonov) are all silent in the face of life, awestruck by its complexity. I’m not sure if any other director has ever gotten at the strange sense of dislocation that hits at the instant when the interior world meets the exterior world. By contrast, Ermek Shinarbaev, who has to be one of the great storytellers in movies, takes the finest psychological threads and traces them down to their frayed ends. By the time you get to the end of My Life on the Tricorn (92), about a severely disaffected young man in the process of negating himself, or the altogether astonishing Revenge (87), in which the urge to wreak vengeance for the murder of a child is followed across two generations and three countries, you feel like vast amounts of ground have been covered and an enormous slice of experience has been contained in one movie. Even Amirkulov’s handmade, sepia-toned, four-years-in-the-making epic, The Fall of Otrar, a pageant of medieval delirium in which the great Khan extinguishes an entire civilization the way a CEO would downsize a corporation, is shot through with the strangest kind of melancholy, brought on by the knowledge that an entire way of life is going to disappear, to be replaced by something monumental, faceless, mysterious.

You can feel variants on this disquiet in the films from Tadjikistan and Uzbekistan, countries with longer histories and more Middle Eastern cultures. In Usmonov’s The Flight of the Bee (98) and his more recent Angel on the Right (02), ancient traditions butt up against the lawless world of the new capitalism. Usmonov’s films describe a bleak reality with good-humored clarity. They are genuine folk art without being folksy: artisanal, anecdotal “little village” stories with bite, such as Mairam Yusupova’s The Time of Yellow Grass (91), which concerns a mountain village coping with the mysterious appearance of a dead body (of an infidel!) in the wilderness. Like Bachtiyar Hudoynazarov’s lyrical Brother (91), a train travelogue through a wasted modern Tadjikistan, Yusupova’s poem of a movie is more landscape-based than the Usmonov films. Yellow Grass is as geared to the mountain community and its pathways as Kiarostami’s Where Is the Friend’s House?, but the presence of that corpse gives the movie a fascinating overtone: it upsets the order of an ancient way of life, and colors the action with an odd sense of foreboding.

Dedicated to Steven Spielberg

Uzbek cinema is informed by a similar tension—cultural history vs. Soviet past vs. a possibly westernized future. Of all the cities we visited, Tashkent is closest to a western metropolis, but a western metropolis where inflation is such that people have to walk around with stacks of currency and the marketplaces suggest the 19th century more than the 21st. Zoulfikar Musakov is the great popularizer of Uzbek cinema, and his Boys in the Sky (02) has reportedly been playing to packed houses in one of Tashkent’s few standing cinemas for months now. An antic, intermittently charming variation on Amarcord (complete with the boys taking a first, forbidden look at porn), there’s an unexpectedly sad undertone to Boys, an unnameable feeling of growing up in an undefined and unsure present. It’s the beauty of these boys and girls that gives the movie its charm—their freshness feels like an echo nearly 40 years after the fact of Elyer Ishmukhamedov’s Uzbek New Wave classic, Tenderness (67). The source of this sadness is made explicit in Rashid Malikov’s allegorical The Mystery of Ferns (92). The specter of Tarkovsky doesn’t exactly hang over Asian post-Soviet cinema, but when it’s there it’s really there (as in Musakov’s cheeky homage to Stalker in his 1991 “science fiction” satire Dedicated to Steven Spielberg). In Malikov’s film, an old professor loses his memory and goes wandering through a series of increasingly fragmented landscapes. The director builds from Tarkovsky’s key move of slow overhead tracking shots surveying stray objects, and makes it pay off: deteriorating individual consciousness is linked to a similarly deteriorating cultural consciousness in a powerfully visceral manner.

If there is a giant who sits astride the history of Uzbek cinema, it’s Ali Khamraev, one of those rare talents like Welles or Godard or Scorsese whose love for the medium is so intense that his best films burst with criss-crossing energies and insights, like a fireworks display. His overly soft last feature Bo Ba Bu (98) aside, Khamraev is a towering figure, a wizard with landscapes (they all seem charged, often enchanted) and an instinctual genius with actors. Anyone interested in the Brechtian idea of the social gestus should study Khamraev’s ferocious 1972 masterpiece Without Fear, which deals with the Soviet modernization of a Muslim village in 1927 and the shock waves caused by the sight of unveiled women. Khamraev’s bravura talent isolates just the right gestures, merging the physical, the visual, and the dramatic with perfect precision. It’s impossible not to see Yusup Razikov’s mordantly funny Orator (00) as a corrective to Khamraev’s Soviet-era knockout: in the Razikov, a gentle Muslim man who just wants to be left alone with his three adoring wives is given the Soviet seal of approval by virtue of his gift for on-the-spot political oratory. Meanwhile, his wives and the peaceful world around him are systematically and unthinkingly “modernized.”

Khamraev and Razikov both work from visual ideas central to Uzbek culture: the patterns of vibrant textiles one sees throughout the country go hand in hand with Razikov’s ornate compositions and the swirling, nearly abstract visual forms of Khamraev’s Man Follows Birds, a mind-bending story of a young thief’s progress in medieval Uzbekistan. In Kirghiz cinema, or in the work of a Turkmen filmmaker like Khodjakuli Narliev, ancient cultural forms are incorporated into the structure and tone of the work itself. Aktan Abdikalikov has gone on record as saying that the rhyming images and movements in his The Adopted Son (98), one of the only films from the region to garner a worldwide audience (and the only one currently in distribution in America), are based on patterns in Kirghiz art (you can see the same kind of pride and care with form in his nearly wordless 1993 film Selkinchek, which may be an even greater achievement than Son, and in the films of Marat Sarulu). In Narliev’s The Daughter-in-Law (72), a film built around the longing of a young woman attached to the memory of her dead husband who is unwilling to give up her solitary life of service to her kindly father-in-law, memories and associations, flashbacks, and wish-fulfilling fantasies continually punctuate the minimal action. But unlike, say, Point Blank or a Resnais film, the temporal shifts are gently lulling, and the net effect is the filmic equivalent of the warm harmonic complexity found in regional rug or fabric patterns. Tolomush Okeev takes on the question of cultural heritage from another angle. The best films of this magnificent artist are as rooted in the rural Kirghiz landscape as Cather’s novels are rooted in the American west. In 1974’s The Fierce One (written by the omnipresent Andrei Konchalovsky, who also wrote Without Fear, Abbasov’s 1961 Uzbek classic Tashkent, City of Bread, and whose 1965 debut The First Teacher is a landmark in Kirghiz cinema), The Skies of Our Childhood (66), and his breathtaking debut short There Are Horses (65), Okeev appears to know every twist, every turn, every rock, every crevice of the mountainous Kirghiz countryside, and every facet of the traditional life lived there, human and animal. Horses, wolves, and dogs have presence and power in Okeev’s movies as they do in no one else’s. Like Khamraev, Okeev is a giant to be reckoned with. He is so revered that Kirghiz Film Studio was renamed in his honor after his untimely death in 2001.

The Daughter-In-Law

Why bother with yet another slew of films from yet another corner of the world? Why indeed. Peter Bart may be a fool, but he’s not the only one asking such questions. So, why bother? Firstly, because we’re told we don’t have to, since we make the best movies here. Examine the logic and transfer it to global politics—it leads all the way to Freedom Fries, Colin Powell’s U.N. charade, and the numbing arrogance that’s led us to Iraq. It all adds up to the kind of bill of goods that can be sold only to a people who jump at the chance to believe in the myth of their own moral and cultural superiority. Secondly, these movies speak from the corner of the world we now dread most, which is why it behooves us to watch them. Thirdly, I’m here to report that there are things in these movies that take my breath away, and that remind me why I fell in love with the cinema in the first place.

Kent Jones is Film Comment’s Editor-at Large. For Ala Verlotsky.