Living Memory: Carlos Saura

During his almost 50 years as a filmmaker, Carlos Saura has been witness to all kinds of convulsions in Spanish cinema and its sociopolitical context. His films, born under the attentive gaze of Franco’s authority and censorship, navigated the transition to democracy with an equal and constant focus on urgent contemporary realities on one hand, and the personal and historical memories and artistic roots of Spanish cultural heritage on the other. A prolific creator (he has made almost 40 features) with a pronounced stylistic and thematic identity, Saura has a strong authorial presence, but the trajectory of his career is closely linked to the work of an interesting group of collaborators.

Born in 1932 in Huesca, Saura spent the civil war years (1936–39) in Republican territory, and this has left an unmistakable imprint on his work. He initially studied engineering but soon gave in to his passion for photography and filmmaking and enrolled in Madrid’s Instituto de Investigaciones y Experiencias Cinematográficas (IIEC), where he would later teach future filmmakers Basilio Martín Patino and Victor Erice, among others. It was here that Saura formulated his filmic ideal. Interested in Italian neorealism, though disenchanted with its excessive sentimentality, Saura found a broad sense of realism, open to surrealist textures, in the films of Luis Buñuel, and would later strive for this in his own filmmaking. This approach was nurtured by Spain’s artistic heritage, and filtered through its early 20th-century culture (poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, composer Manuel de Falla). The IIEC was to become one of the intellectual centers that gave rise to the Nuevo Cine Español (NCE), a movement that rebelled against the patriotic historical narratives that were predominant in Fifties Spanish cinema. Although Saura didn’t fully participate in the NCE (he has always considered himself an outsider) two of his films, The Delinquents (59) and The Hunt (66), are considered among the movement’s forerunners and milestones.

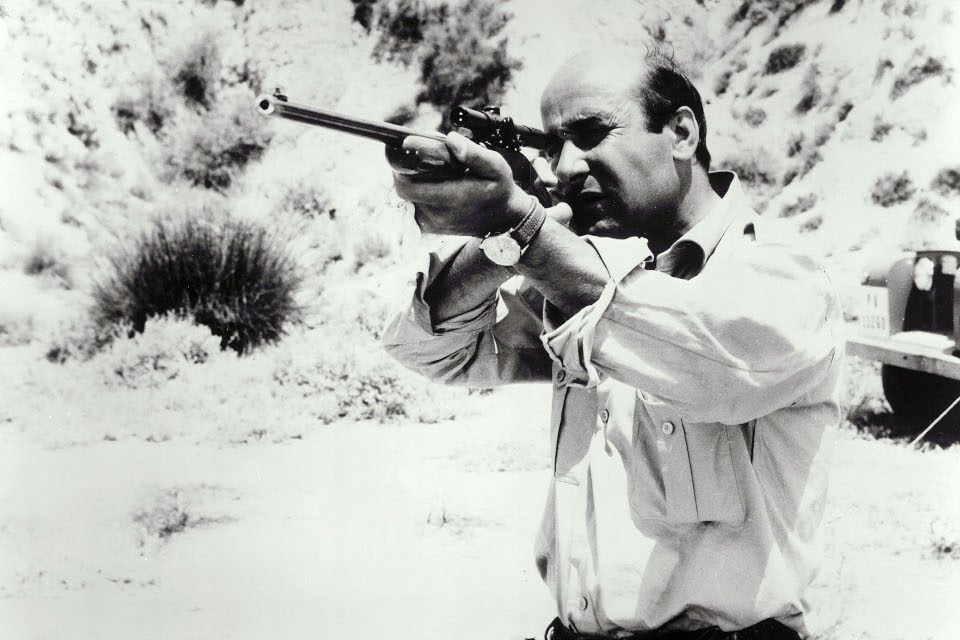

The Hunt

Saura’s medium-length documentary Cuenca (58), a poetic interpretation of reality imbued with the spirit of Buñuel’s 1933 film Land Without Bread, was followed by his feature debut, The Delinquents. The critical realism of the latter links the Spanish neorealist revival of the Fifties (represented by such filmmakers as José Luis Berlanga and Juan Antonio Bardem) with the NCE of the Sixties. Experimental in its form, audacious in its editing, distanced in narrative style, and completely refraining from making moral statements of any kind, The Delinquents was comparable to the first, contemporaneous works of the French Nouvelle Vague. In this story of the stunted hopes of a group of youths from Madrid’s outskirts, Saura’s tone comes close to the “suburban picaresque” of writer Pío Baroja.

For his follow-up, Weeping for a Bandit (64), the director briefly tried his hand at the commercial bandolerismo genre, which resembles the western but with nationalist/populist-epic tendencies. He found the experience unsatisfactory and two years later returned to realism with The Hunt, one of his best and most acclaimed films. Consisting of very minimal elements—four characters hunting in a desolate landscape—the film constructs an allegory about the legacy of pain and trauma left behind by the Civil War and its ideological battles, now 20 years distant. It’s a political parable about the resentment and hostility of a society suspended in a moral void. Via voiceover, the story moves dialectically between objective and subjective perspectives, advancing serenely until it explodes into violence and becomes an exploration of a ferocious aesthetic of cruelty.

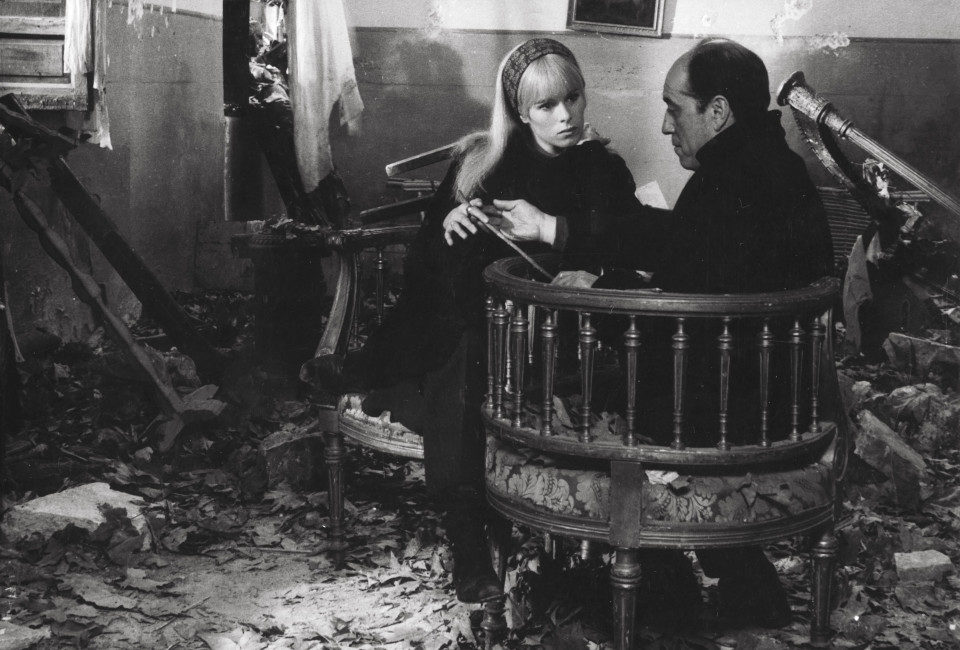

The Hunt was the first Saura film produced by Elías Querejeta, with whom the director went on to establish a long-standing professional relationship. Their 12 collaborations constitute perhaps the most interesting and compact phase of Saura’s career. With Peppermint Frappé (67), Saura’s regular creative team further expanded to include screenwriter Rafael Azcona, who would co-author six more films with the director, and actress Geraldine Chaplin, who would be his muse and partner for over a decade. Saura’s work with Chaplin is fascinating both in narrative terms (she typically incarnates the role of the foreign woman, i.e. permanent object of desire) and metacinematic ones (we are privileged to observe the physical and artistic growth of a figure as it traverses a series of films almost like a specter).

Saura’s next three films, which describe the hypocrisy and disenchantment of the bourgeoisie, are infused with experimentation. While Peppermint Frappé confronts the Spanish middle class with its own confusion—lost as they are in a schizophrenic dialectic between the old conservative ways and a sophisticated modernity—the road movie Stress Is Three (68), with its references to Polanski’s Knife in the Water, punctures the boredom of a bourgeoisie drifting aimlessly in a moral vacuum. Honeycomb (69), meanwhile, describes the games of power and submission played out by a bourgeois couple immersed in affective and existential chaos. Several of the components that will later guide Saura’s future output become apparent here: the presence of religious symbols, sexual fetishism (inherited from Buñuel), surrealist and dreamlike undertones, memory games, and a marked theatricality.

Peppermint Frappé

During this phase of his career, Saura made a series of films in which individual memory becomes collective within the context of the civil war. In The Garden of Delights (70), a character’s exclamation “Symbols are what matter!” summarizes another pillar of Saura’s expressive strategy. His is a metaphoric cinema in which memory functions as an organic space, not fixed, but filtered through the open wounds of the present. The Garden of Delights, Anna and the Wolves (73), and Cousin Angelica (74) explore, through subjective perspectives, the possibilities inherent in an allegorical text—typical of films that predate Franco’s death. They reflect on the Spanish nation’s identity crisis and the devaluation of family values amongst a bourgeoisie asphyxiated by militarism, sexual taboos, and religious fanaticism. After the dictator’s death, Saura went on to make two films back to back that deepen his exploration of memory and dreams. In Cría cuervos! (76) he depicts reality from the innocent and amoral perspective of a child, and in Elisa, My Life (77) he utilizes a complex narrative artifice in which different levels of fiction (filmic, literary, real, or imaginary) interconnect. Both films deal with private interpersonal conflicts without suggesting a national or social dimension. Soon after, Blindfolded Eyes (78) and Mama Turns 100 (79) brought this stage of Saura’s career to an end.

As a bridge to the next series of projects, the director made Faster, Faster (81), an interesting return to the suburban environments of The Delinquents. A linear and realist story propelled by the urge to take stock of present-day Spain, the film is a portrait of nihilistic and disoriented youth wavering between the immediate prospect of a fatal destiny and the search for a new existential horizon.

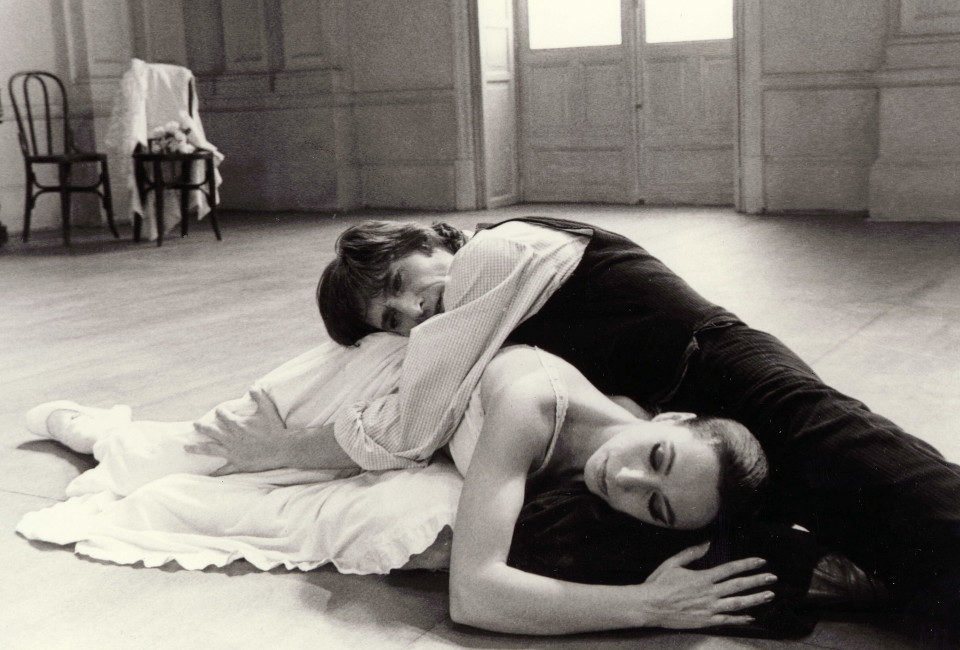

With 1981’s Blood Wedding Saura embarked on a flamenco musical trilogy that includes Carmen (83) and El amor brujo (86), a project shared with the producer Emiliano Piedra and the dancer and choreographer Antonio Gades. The first part of the series, which is the most fascinating of the three for its clear, clean, and stripped-down approximation of its source, is an adaptation of the play by Federico García Lorca. Eschewing a conventional adaptation, the film is structured as a look at the artistic process through a dress rehearsal of Lorca’s tragedy by Gades’s ballet company. Saura sets up a deferential interplay between film, ballet, literature, and flamenco music through the formal rhythm created between detailed close-ups of the dancers’ bodies and observational wide-angles of the action, which unfolds on a bare stage. But the clarity of Blood Wedding was overshadowed by the more complex and sophisticated relationship established between the different modes of artistic expression in Carmen, based on both the novel by Mérimée and the opera by Bizet. El amor brujo, inspired by Manuel de Falla’s ballet music, adopts a more conventional staging strategy, with only one level of fiction—that of the original piece. In his effort to create a dialogue between the heritage of popular culture and “high” culture, Saura produces a reflection on the tragic weight of tradition in hermetically closed cultural contexts—a theme that reverberates throughout his oeuvre.

Blood Wedding

Parallel to this musical project, Saura shot Sweet Hours (81), again exploring the idea of memory as a stage for representation, and a commissioned film, Antonieta (82), a reminiscence of Mexico’s early 20th-century political and social convulsions from a script by Jean-Claude Carrière. Next came The Stilts (84), which takes on the subject of old age from an intimate point of view but lacks Saura’s usual narrative tricks. Following this phase, Saura made three historical films. The first, El Dorado (88), is a superproduction that depicts the historical reality behind the 16th-century conquistadors’ quest for the mythic golden city of the Incas. In its detailing of the conflicts and divisions among the colonizers during their chimerical expedition, there are distinct echoes of the civil war. Then, in The Dark Night (89), about St. John of the Cross, the director delves into the origins of religious repression, a theme present in his films since the Sixties. Lastly, ¡Ay, Carmela! (90), based on a play by Sanchís Sinisterra, proposes a novel approach to civil war events, by way of tragicomedy and an almost documentary realism.

In the Nineties, in the context of Spain’s social and political stability, Saura’s films moved along three creative paths that evolved in tandem. First, he continued his aesthetic exploration of musical and folkloric dance forms with Sevillanas (92) and Flamenco (95), both of which are documentary inventories of different subgenres of flamenco performance. The latter marks the beginning of a collaboration with cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, giving his staged, theatrical, and abstract conceptions a much more stylized, rather flamboyant imprint. Then, Tango (98) and Salomé (02) represented returns to the same narrative strategy used in Carmen: a metalinguistic game in which different levels of fiction commingle and reflect on the process of art making. This trajectory continues through to Iberia (05), a documentary in which several kinds of Spanish dance are performed to Isaac Albéniz’s eponymous musical composition.

Since the early Nineties, Saura has revisited a number of familiar subjects with less fruitful results, making films that attempted to depict some of the varied realities of modern Spain. Outrage (93) and Taxi (96) are acts of witnessing in the same vein as The Delinquents and Faster, Faster, realistic and tragic portraits of marginal urban environments plagued by underlying violent and even neofascist behavior, but neither film fully develops its material. Little Bird (97) is a return to the territory of Saura’s Seventies period, with the familiar games of appearances, upper-class hypocrisy, and esoteric textures, but without any strong allegorical dimension. Finally, in The Seventh Day (04), Saura draws a crude portrait of “deep Spain,” based on a true story by the writer Ray Loriga: the rural, ancestral, isolated Spain, in which festering resentment builds inevitably toward violence and death.

Sweet Hours

The most recent thread in Saura’s work, still open and active, consists of different takes on two artists whose influence is evident in much of his work. In Goya in Bordeaux (99), the director draws an imaginary portrait of the final years of the Spanish painter, living in exile in France, as he recalls scenes from his life. Again death, dreams, and memory appear as an organic territory, explored by Saura and Storaro through a mise en scène that evokes theatrical and pictorial paradigms. Finally, Buñuel and King Solomon’s Table (01) is a tangled and unsuccessful film-hypothesis in which the anachronistic present-day appearance of a young Buñuel is intended to evoke the legendary director’s imaginary world by intermingling references to the creative universes of his friends Salvador Dalí and García Lorca.

If Saura’s work in the Sixties and Seventies is distinguished by its vitality, drive, and sociopolitical relevance, it has to be said that since the mid-Eighties his films have shown signs of increasing fatigue. In the latter half of his career there’s a clear effort to maintain a certain balance between folk-culture research, social portraits, and the study of their origins, but Saura’s preoccupations and methods now seem outmoded; his later films are pale shadows of his earlier, socially engaged work. It might be said that the center of gravity in his work has shifted from a concern with Spain’s historical national memory in the films of the Sixties and Seventies to a discourse that is more closed off and self-referential, with a tendency to reinterpret earlier subjects from the films of the Eighties and Nineties. Saura was unquestionably Spanish Cinema’s standard-bearer at a time when there was a clear need for films to react against the artistic and social amnesia of the late Franco era. Since then, he has moved more to the margins, making way for subsequent generations of filmmakers, those who have continued to write the history of Spanish cinema.

Translated by Marcela Goglio