Letter to an Unknown Decade

By most accounts, cinema shrank Benjamin Button–style in the 2010s. Movies, once larger than life, became portable, foldable, and smaller than your palm. But my history of cinema—and my own, individual cinephilia—progressed in the other, “correct” direction. In 2019, my defining cinematic experiences were on the big screen: the longing-soaked oceans and electronic rhythms of Mati Diop’s Atlantics washing over me in a theater in Toronto; the lush colors and outsize emotions of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women holding me in thrall in a screening room in New York. In 2010, when I was a 14-year-old in a small city in central India, my most thrilling movie experience was watching The Social Network via a Torrented file on my laptop, obsessively pausing and rewinding and replaying the film to parse what Aaron Sorkin’s rapid-fire dialogue and David Fincher’s frenzied, cross-cutting storytelling had to say about the world around me and the world soon to come.

I begin with this personal anecdote to concede, preemptively, the futility of any attempt at reckoning authoritatively with a decade of cinema. This is not just because 10 years is a long time, but because such periodizations of culture leave unaddressed questions of place and experience. Becoming a cinephile across two continents this past decade has made me acutely aware of both the disorienting (and unequal) multiplicities of histories being written at any given time, and the corporate homogeneity that dissolves them into totalizing master-discourses. This is true even—or rather, especially—in today’s moment of seeming plenitude, access, and interconnectedness, which Fincher’s film telegraphed with such chilling prescience in 2010. In the resulting indiscriminate glut, only metrics and trends and consensus narratives (all of which are usually inextricable from a profit motive) rise to the surface.

Last February, I had the rare but distinct feeling that I was in the presence of history-in-the-making when I attended a two-day, conference-style event at Barnard College and the New School, called the “Dalit Film and Cultural Festival.” Celebrating an emerging, radical new wave of cinema by filmmakers from India’s marginalized Dalit or “untouchable” caste, the festival was the first of its kind, and the two seminal films it showcased—Fandry (2013), by Marathi filmmaker Nagraj Manjule, and Kaala (2018), by Tamil director Pa. Ranjith—struck me as decade-defining achievements by most yardsticks. Fandry turns rage into poetry, its lyrical, ethnographic portrait of injustice ending with a rock hurled at the screen; Kaala culminates in a setpiece that turns class solidarity into a thrilling, fantastical spectacle of music and color. Seamlessly combining popular forms with both lived experience and an erudite politics, they’re sui generis works, and watching the young directors present them to a visibly moved audience, I felt like I was witnessing a revolution. But then I left the event and went downtown to Metrograph to watch a live broadcast of the Academy Awards, in whose obit reel I noticed the absence of a recently passed titan of Indian cinema, Mrinal Sen. And I confronted the realization that one person’s revolution is barely a blip in another person’s canon.

Kaala (Pa. Ranjith, 2018)

All of which is to say that any accounting of the past decade of cinema must start with the question: whose decade? And whose cinema? Becoming a critic (and thus, a historian) in the last 10 years has meant negotiating that elusive threshold where the personal, the marginal, and the vernacular turn into the historical. One of the defining images of my decade, and one which illustrates this need for particularity with stunning intelligence, is from Kirsten Johnson’s 2016 documentary Cameraperson. A shot of a vast gray sky in Missouri is ruptured by a bolt of lightning—which elicits a gasp from behind the camera, and then a series of sneezes that make the whole image quiver, unbalanced. The many such gestures of affect and intervention that Johnson weaves into her cine-memoir dismantle assumptions about objectivity and authorship to create an alternate record of image-making—one which recognizes that images are necessarily contingent, caught in irreproducible (and ultimately unrecordable) webs of time and place and persons. I keep her film in mind as a guide for my criticism: a reminder that to write about movies is to write about our encounters with them—to not just contemplate the sky and its bursts of lightning but also to tell the story of one’s gasps and sneezes, even if they end up on the floor of history’s editing room.

I encountered Christian Petzold’s Transit earlier this year on a flight from Berlin to Los Angeles. (So much for my big-screen cinephilia!) And walking in and out of immigration at both airports, I felt the ghosts of the film’s Kafkaesque bureaucracy of borders around me, unchanged yet sharpened into something new. Transit is one of many films from the last few years that contend with the flows of people and capital that characterize contemporary life—flows that dissolve borders in some ways, while reifying them in others. These movies examine the intersections and perversities of globalization, challenging our ideas of nationhood and national cinemas. In Valeska Grisebach’s magnificent Western (2017), a German construction worker stationed in a Bulgarian border-village is alienated by the jingoism of his colleagues and filled with longing for the communal bonds of the locals. In American Factory (2019), Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar capture the degradations of multinational capitalism, while Nadav Lapid’s Synonyms (2019) wrestles with the corruptions of nationalisms in its protagonist’s tortured linguistic efforts to assimilate in France. And Lucrecia Martel’s monumental Zama (2017)—my film of the decade—is closely attuned to the nuances (and violences) of seeing and speaking across cultures, unearthing colonialism and its bloody migrations as the foundational logic of Latin America.

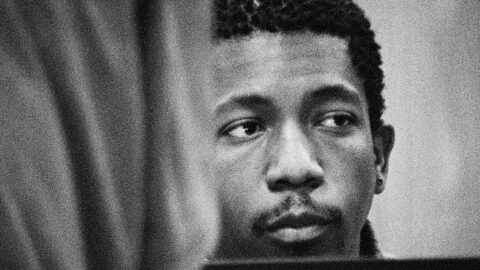

Beyond our notions of place, these films also complicate our notions of identity, embracing the particular rather than striving for universality—an illusory standard applied unfairly, even now, to films whose subjects are not white, Western, heterosexual, normative. The most influential movies of the last decade have been defiantly specific, refusing to compromise the rootedness of their perspective to pander to a broader audience. Barry Jenkins is a practitioner par excellence of this tendency: his Oscar-winning Moonlight, embroidered exquisitely with the sonic and visual details of his and screenwriter Tarell Alvin McCraney’s lives in Florida, introduced new idioms of possibility into the American indie film. I had the privilege of attending the premiere of Moonlight at the 2016 Telluride Film Festival with a group of other film students and witnessing the meteoric rise of a major talent in real time.

Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016)

Most of us were awed by Jenkins’s film, but one young contrarian in our group complained that he felt it “didn’t make room” for him. In retrospect, his comment seems to me to reflect how unusual it was at the time for a film as accessible as Moonlight—a quintessentially American coming-of-age melodrama—to not offer all its viewers the classical, humanist pleasures of identification. Instead, it demanded an awareness of one’s social position as spectator, as does the work of Terence Nance and Jordan Peele to different (but equally masterful) ends. Many other films that left an impression on me this past decade did something similar: they didn’t necessarily make me “feel seen”—i.e., succeed in the noble, but often superficial, goal of representation—but they revealed to me how I see. Certain images from Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013) are nestled deep in my mind, haunting me with their profound denaturing of the experience of perceiving the world, and being perceived by it, as a woman. Magic Mike (2012) and Magic Mike XXL (2015) provoked something more joyous with their reprogramming of cinematic spectacle around (heterosexual) women’s scopophilia.

In this decade of particularities and specificities, is there anything that is universal about cinema? Perhaps only fears of its death. In metaphorical terms, cinema has been dying since before I was born. In literal terms, cinema has always been combustible, degradable, scratchable; now, it’s deletable and unsearchable. Films that contend with this ultimate contingency strike me as the most urgent: Garrett Bradley’s 27-minute America devotes itself to recreating lost histories of Black cinema; Thomas Heise’s nearly four-hour Heimat Is a Space in Time uses archival objects to recover the fast-fading lessons of Germany’s past. But now, as the always imminent end of cinema seems to pale in comparison to the assured end of our planet, the images that I cling to are not self-reflexive, but elemental: the serene, nurturing woods of Valérie Massadian’s Nana (2011); the roiling seas of Helena Wittman’s Drift (2017); the arid, cracked farmland of Nila Madhab Panda’s Dark Wind (2017) and the cyclone-wrecked coastal villages seen on TVs within the film. Like the best of movies, these films point us to the richness—now under siege—of the worlds outside of the screen.