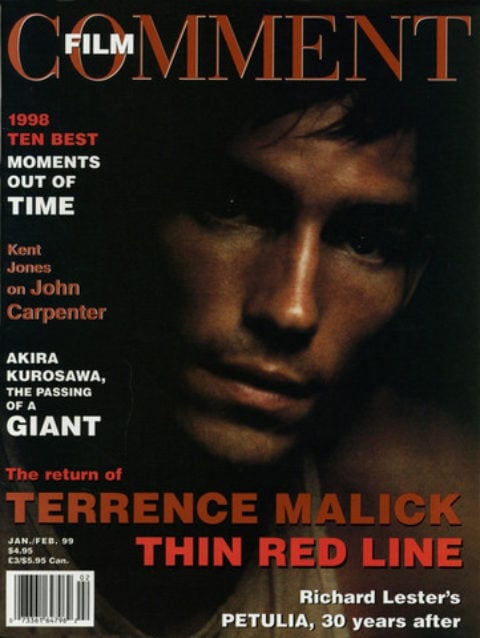

Let There Be Light: The Thin Red Line

Ordered to advance up a long hill towards concealed Japanese positions in broad daylight, a callow Infantry lieutenant, a kid really, signals to his two scouts to advance, then, when they don't move, signals again, more forcefully. The two GIs trade looks, and are up and running. From above, the first shots of this battle erupt: two brief bursts drop both men and silence falls again. The long grass ripples in the breeze and then magnificent sunlight unfolds across the landscape, as if a signal from the heavens. The lieutenant sounds the charge and he and his men rise up and rush forwards to be decimated by the machine-gun nests and mortars lying in wait for them. That glorious epiphany of radiance and the terrible carnage that ensues together form one breathtaking movement, and encapsulate one of the main principles at work in Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line.

There has truly never been a film about modern war quite like this one: a kind of lyric epic poem about the way men are transformed for good by the experience of war, carefully balancing romanticism and dispassion, action and introspection. Like Malick’s Badlands and Days of Heaven, it is spare, fleet, elliptical, and establishes a careful middle-distance from the circumstances of its characters, disarming the processes of audience identification and implication for all but the briefest of moments. More significantly, and unlike Saving Private Ryan, it also seems determined to evade the mythopoeic impulse—that which makes a film larger than life and proffers it to stand in for history.

Adapted from James Jones’s 1962 novel, The Thin Red Line chronicles the experiences of the men of Charlie Company who are part of the American force charged with seizing the strategically important tropical island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese in 1942-43. With certain notable additions and adjustments, Malick extracts his basic events and characters intact from Jones’s narrative: the disembarkation, landing, and march inland of the Company; the Company’s protracted battle to take a hill stubbornly defended by Japanese troops, which is the main body of the film; a period of r &r away from the front after the Company’s victory; the self-sacrifice of a soldier that enables his Company to escape from advancing Japanese forces, also invented by Malick; the departure of the surviving members of the company from Guadalcanal.

Where Saving Private Ryan establishes its primary characters within minutes, and its secondary ones by the beginning of its second act, and then creates a GI microcosm through the device of the mission, The Thin Red Line is more of an ensemble film and takes a much more leisurely and oblique approach—you may be halfway into the film before you figure out who you should be watching in narrative terms; even then, Malick keeps directing your attention to somebody you’ve never seen before and may never see again, which presents minor problems of emphasis when recognizable actors like Woody Harrelson briefly pass through. There is little sense of the camaraderie associated with WWII (or is it only WWII films?); you get the feeling these men barely know and don’t much like each other, and Malick refuses to be sentimental. Like Jones’s novel, the film doesn’t have a protagonist, but shifts from one character’s point of view to another. But where Jones scrutinizes the calculations and rationalizations going on in his characters’ heads to show that their actions are determined as much by, for example, preoccupation with how others perceive them as by fear of death, Malick by contrast takes most of his characters at face value. In fact, he pointedly keeps all but a few of them deliberately sketchy and undefined. The only defining moments that matter to him are those that convey a significant response to or perspective on war as an experiential event of the profoundest magnitude. As much as anything, the raison d’tre of the stunning sequence where Captain Gaff (John Cusack) leads a small group of men in an attack on an impregnable machine-gun bunker complex is to witness the emotional aftermath for the survivors on both sides. Though Malick has inherited his title from Jones, who in turn derived it from an old Midwestern saying, “There’s only a thin red line between the sane and the mad,” his film is as much about the psychic fortifications men construct in order to survive war as it is about its psychic and moral consequences.

One of the key elements of the unique cinematic idiom Malick established in his first two films was his use of refractive voiceover. It is equally integral to the articulation of The Thin Red Line, if not more so, but there are pronounced differences in how it is applied. Where the earlier films offer a single (more naïve than unreliable) narrator, The Thin Red Line dispenses with narration altogether, replacing it with multiple subjective voiceovers (sometimes accompanied by fleeting visual flashbacks) that insinuate themselves into the action as it proceeds. These fleeting glimpses into the characters’ souls or semi-coherent fragments of thought are presented in a variety of registers, from naturalistic to poetic. But just as the narrations in Malick’s earlier films create a certain poignant distance, here direct access to the inner lives of these men, however glancing and intermittent, creates a singular push-pull of intimacy and distance, and reinforces the sense of the GIs’ isolation from one another: each is imprisoned in his subjecthood.

There is nothing systematic about how Malick deploys this device: some characters are heard from only once, others frequently. But for the most part the relevance of their sentiments derives from their diverging philosophical implications, which add up to a spectrum of bitter wisdoms and consoling beliefs: the Christianity of Captain Staros (Elias Koteas), who prays for the safety of his men; the regressive savagery of Private Dale (Arie Verveen), who collects the gold-filled teeth of dead Japs; the mystical connection Bell (Ben Chaplin) feels towards the wife he loves; and the hard pragmatism of Colonel Tall (Nick Nolte), who expends soldiers’ lives in the hope of jump-starting a stalled career. (We are afforded several poignant glimpses of his horrified self-awareness.) These take their place alongside a number of more conventionally observed moments and pronouncements: the matter-of-fact, every-man-for-himself existentialism of Sergeant Welsh (Sean Penn), who has no illusions about what wars are fought over: “Property. The whole thing’s about fucking property”; the young GI on the troop ship who puts his faith in the Lord and in the next breath talks of buying a car when he gets home; the breakdown of Sergeant McCron (John Savage), first seen leading his men in prayer aboard the landing craft, later, mind broken by the futility of his best efforts, raving “We’re just dirt.”

If there is a central character in The Thin Red Line, it is Private Witt (Jim Caviezel), an enigmatic and charismatic presence, who marches to a different drummer, much like Martin Sheen’s Kit in Badlands. This minor character in the novel, a “crazy sentimental Kentuckian” sharp-shooter who longs for a chance to save the lives of his fellow soldiers, is reinvented as a serene Emersonian idealist with negative capability to spare. His speculative voiceover, frequently framed in unanswered questions, contemplates man’s fallen spiritual condition and yearns for communion with the sublime in decidedly poetic cadences: “Why can’t we stay on the heights, the heights we’re capable of? We know the glory for a while and then fall back into separateness, strife, division.”

Witt’s apartness and affinity for Otherness is clear from the outset: in a prologue that is entirely Malick’s invention, we see him living among the Melanesians, the indigenous people of the Solomon Islands, leading an idyllic existence, clearly AWOL. As punishment, he is transferred to stretcher-bearer duty, then later rejoins Charlie Company during the fighting. Whether tending to the wounded or in the thick of combat, Witt functions as an representation of near-extinct American Transcendentalism (to which allusion is also made in the use of Charles Ives’s music). From the vantage point of a romantic philosophical perspective, Witt can contemplate his own death and formulate a response. Recalling his mother’s death, in words that carry a faint echo of Linda Manz’s narration in Days of Heaven, he thinks: “I couldn’t find nothing beautiful or uplifting about her going back to God…. I heard people talking about immortality, but I ain’t seen it. I wondered how it would be when I died, what it’d be like to know that this breath now was the last one you were ever going to draw. I just hope I can meet it the same way she did, with the same calm. Because that’s where it’s hidden, the immortality I haven’t seen.”

If Saving Private Ryan offers a kind of total experience of war, deeply invested in enthralling spectacle, unassailable visual mastery, and the rejuvenation of a specific iconography of archetypal characters and symbolic situations, then The Thin Red Line proposes a more abstracted or interiorized antispectacle, in which the viewer’s attention is repeatedly directed away from “the action” and towards ostensibly irrelevant sights and sounds. The distancing sound techniques Malick first deployed in Badlands are all present and correct here: recessive sound shifts, silence, foregrounding of music, and voiceover. The genuinely radical sense of visual emphasis that he developed in Days of Heaven is also in place: the disregard for prevailing narrative cinema conventions concerning the visually admissible and inadmissible, which at the time were dismissed as an unseemly, self-indulgent preoccupation with minutiae and the scenic.

This time around Malick is more successful in integrating his transcendental aesthetics with his thematic framework. In Witt, who is in a sense an incarnation of negative capability—that is, a heightened receptivity to and empathy with any chosen object of contemplation—Malick has devised a more fitting “protagonist” than Richard Gere’s more decorative than imaginatively active Bill in Days of Heaven. Witt isn’t the protagonist of a war film, however, but of an adventure in sensory and spiritual wonder. All of Malick’s films uproot their characters from civilization and deposit them in nature’s domain, but Witt is the first of them to behold the eternal confrontation of nature and culture for what it is, and to be able to articulate a metaphysical perspective: “One man looks at a dying bird and sees universal pain. Another sees that same bird, feels the glory, feels somethin’ smiling through it.” These words, which correspond to an earlier image in the film, encapsulate the duality of horror and rapture of existence, which war brings into sharp relief: that even—no, especially—in the throes of self-annihilation, man can apprehend the sublime.

In each of Malick’s films, the world is fallen and tainted, and the affairs of man are ultimately bleak and insignificant, warranting neither sentimentality nor pathos, let alone grace. Only Witt stands outside this. Seen in that light, the reconciliation of transitory human affairs and the eternal physical world, of culture and nature, willed by the imperatives of Malick’s visual inclusivity, holds out the possibility of redemption and transcendence. In the economy of images in The Thin Red Line, as in Days of Heaven, the visual “surplus” of shots of animal, bird, and plant life, of jungle, sky, water, texture, space, and light, impose metaphysical perspective and reaffirm an order and harmony in the world that makes a war pale in significance. That’s not to say that by some perverse gesture the shots of blades of grass and fruit bats now take precedence over the narrative: on the contrary, the true film exists at the place where the narrative and the ineffable meet as equals. The interplay of the self-evidently fateful and the seemingly inconsequential or circumstantial holds the promise of authentic if transient metaphysical epiphany. To take an example: just before the fighting resumes on the hill, a young GI lying in the grass reaches out to touch a tiny leaf, whose delicate fronds gently close on contact. This interpolation, as immaterial as it is exquisite, is absolutely representative of Malick’s cinematic sensibility.

Above all, Malick expresses the transcendental imperative in terms of light. It is forever in the Emersonian cadences of Witt’s thoughts: “Darkness, light, strife, and love, are they the workings of one mind? The features of the same face? Oh my soul, let me be in you now, look out through my eyes, look out at the things you made, all things shining.” In their final conversation, a strange Conradian bond having formed between them, Sgt. Welsh mockingly asks Witt, “You still believing in the beautiful light, are you?” Quietly adding, “How do you do that?”, Penn captures a subtle shift in Welsh, suggesting a man who, after all he’s been through, is no longer secure in his beliefs. Witt responds, “I still see a spark in you.” Early on in the film a young soldier dies, looking upwards, and Malick cuts to the bright sun directly overhead, its rays shining down through the trees’ leaves. In that terrible moment once again there is rapture and grace, a union of the profound and the inconsequential, one more moment of transcendence. All things shining indeed.