Le Cinéma du Glut

The cast of thousands in Steven Spielberg’s future-set virtual reality epic Ready Player One is a bit like an exploded comic con, the collective crossover event labor of an army of pixel pushers and IP rights negotiators. Faces in the surging crowds of avatars include Freddy Krueger, Spawn, Beetlejuice, Street Fighter II’s Chun Li, Gundam, and the Battletoads from the 1991 video game of the same name; among the toy chest of fetish objects are the Holy Hand Grenade from Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), a scissor-doored DeLorean à la Back to the Future (1985), and a Madball, the brand of foam bouncy balls bearing gnarly, grotesque faces which were popular in the schoolyards of the 1980s. In the film’s teeming crowd scenes, 30-odd years of accumulated popular-culture iconography can be seen cluttering the screen.

Spielberg’s film is set in a metastasized Columbus, Ohio, where teenaged protagonist Wade Watts lives in a favela-esque vertical shantytown of piled-up trailers called “The Stacks.” Watts’s dismal, dystopian real life, however, is of only ancillary importance to the second life he leads as Parzival in the OASIS, the immersive, endlessly variegated VR environment in which he spends most of his time. The OASIS is the co-creation of the deceased James Halliday, a pop-culture obsessive who spent his adolescence in the heyday of the Atari 2600, and who left behind as his legacy a series of challenges to be faced in order to uncover an Easter Egg buried in his game that entitles the finder to Halliday’s shares in his company. Like the Ernest Cline novel on which it’s based, Ready Player One is a jubilant paean to the pleasures of popular culture, and it is so effective as such that you might almost overlook the fact that it posits a 21st-century pop culture that is saturated in the pop iconography of the late 20th century. Though the movie is set in 2045, its index of references seems to end around the turn of the millennium. It’s a future where pop seems to have stopped.

Halliday, an absent-minded narcissist at least partly to blame for affixing his antique obsessions to a new generation, is a combination of a benevolent version of the lovelorn, charm-challenged Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network (2010), Willy Wonka, and Spielberg in his over-the-top gamemaster mode. Any definition of what constitutes “excess” exists along a sliding scale: no one ever considered Spielberg a model of austere restraint as a younger man, but with a recent run of decorous, civic-minded pictures appearing amid a multiplex lineup overwhelmingly defined by incoherence, cynicism, crudity, and cruelty, he has lately been pulling off a reasonable enough impression of a bastion of classicism. With Ready Player One, however, the sober Spielberg, the grown-up in the room, has again become the sugar-high Spielberg, the ageless boy wonder, the early cinephile adapter of what would come to be known as “gamer” culture, the proud owner of a collection of vintage arcade consoles, the 71-year-old Peter Pan, toggling between artist and entertainer avatars.

Ready Player One

For years, the go-to knock against Spielberg was to attack this perceived Pan-ism, his steadfast refusal to put away childish things, and a thousand mostly indistinguishable screeds have accused him of smothering the New Hollywood renaissance in its crib by helping to invent the modern tentpole blockbuster and thus clearing the way for the reign of sensorial overload and the “infantilization” of moviegoers who’d once been so near to attaining sophisticated spectatorship. Such distinctions between an adult and an adolescent sensibility, however, may be less important than they used to be—at least if you listen to the 2013 PDF manifesto “Youth Mode: The Death of Age” by K-HOLE, a New York–based “trend forecasting group” whose missives are directed toward an art-world, rather than corporate, clientele.

“For a while,” K-HOLE writes, “age came wrapped up in a bundle of social expectations. But when Boomerang kids return to their parents’ Empty Nests and retirement fades into the horizon, the bond between social expectations and age begins to dissolve. We’re left using technological aptitude to divide the olds from the youngs—even though moms get addicted to Candy Crush, too. Demography is dead, yet marketers will quietly invent another generation on demand. Clients are desperate to adapt. But to what? Generational linearity is gone. An ageless youth demands emancipation.”

Oblivious, technology-dependent Millennials catch heat for a lot in our slightly-over-halfway-dystopian contemporary reality, but as often as not when you’re looking for the source of the beacon-like Smartphone light spoiling the dark of the cinema the culprit is a candidate for AARP membership. When every mid-sized American city boasts some variation on the Barcade formula, Spielberg’s lifelong Pan-ism seems less abnormal or anomalous than prophetic, his creative life exemplifying the breakdown of “generational linearity.” Elsewhere in “Youth Mode,” the authors define the post-countercultural concept dubbed “Mass Indie,” described as having “an additive conception of how culture works. Identities aren’t mutually exclusive. They’re always ripe for new combinations.”

Unfriended

The recycling of proven formulas in popular cinema has been with us for as long as a pop cinema has existed—Spielberg’s Indiana Jones, to take one example, is the direct offspring of the kid’s adventure serials of the 1930s and ’40s—but Ready Player One’s hotchpotch accumulation of the detritus of recognizable pop iconography is something different. Like few feature films before it, Spielberg’s movie exemplifies an aesthetic of pop-culture decoupage that has developed, in recognizably kindred forms, across a wide range of media, one that has been increasingly prevalent through the early years of the 21st century. It is that of the junk-pile jumble of accumulated mass-manufactured character properties at the end of pop history—the aesthetic of glut.

The pop past is increasingly present in the Internet era. In the 2010 book Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, music journalist Simon Reynolds discusses this state of affairs as it affects pop music, analyzing a perceived deceleration of creative innovation as music began to drag ass under the accumulated ballast of its suddenly ever-present, Internet-accessible yesteryear. “Instead of being about itself,” Reynolds argues of the then-just-closed first decade of the millennium, “The 2000s has been about every other previous decade happening again all at once”—a fair enough descriptor of the OASIS. This sense of cultural stall was acutely felt in music around the time of Reynolds’s writing, most pointedly in the craze for sample-suturing mash-ups best exemplified today in the work of DJ George Costanza, nom-de-web of David Wightman, who creates exhaustively researched, barrel-scraper tours of little-mourned idioms: pop-punk, Third Wave ska, country-rap, etc.

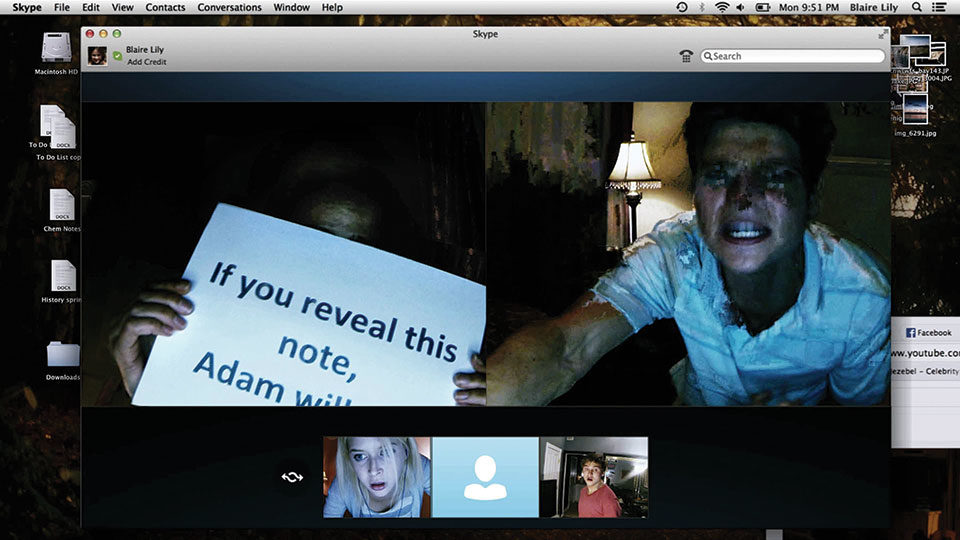

Ready Player One is about as near as a multiplex movie has come to a mash-up, for the sclerotic cinema has grown technophobic in its dotage. Excepting a handful of movies exploring the possibilities of screenshot mise en scène, like Unfriended (2014), crossover curios like Smosh: The Movie (2015) or The Emoji Movie (2017), and outliers like Blackhat (2015) and The Human Surge (2016) that exemplify post-digital life, Internet culture and wide-release cinema have remained discrete phenomena. Films have been tentative or indifferent about seeking cinematic means to integrate into a narrative context the complete alteration of daily life represented by the Internet. A direct analogy between Reynolds’s conclusions about the state of music and the cinema doesn’t hold water—those of us who feel a connection to and responsibility for film history only wish that it were ubiquitously present in the life of the lay viewer. In fact it often feels less so today in the era of ironclad algorithm-reinforced taste-based filter bubbles into which no unvetted “content” can penetrate than it might have in the heyday of Million Dollar Movie and film society screenings. (Spielberg, for his part, offers a dissenting opinion to Reynolds’s in a recent Time interview, positing that “Social media is keeping people pretty much focused on the present… [It] may be the beta-blocker to nostalgia.”)

TV Carnage

New films still regularly arrive to displace the old, yes, but the properties and characters are very often familiar ones. This state of affairs has long been the case as concerns certain mythic and folkloric sources for pop cinema—after all, there can only be one Journey to the West or Loyal 47 Ronin or Gunfight at the OK Corral, and they offer relatively fixed narratives. But it is somewhat unusual for pop cinema itself, traditionally flexible, supple, and responsive where myth and folk sources were unchanging, anchored, and monolithic. George Lucas dipped into world mythology in creating Star Wars, but he also snagged spare parts from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials. Each generation received stories, heroes, and villains tailored to their perceived identifying values—Rush Hour (1998) was a ’90s Tango & Cash (1989), which in its day had been an ’80s Freebie and the Bean (1974). By contrast, the new Star Wars is literally just a new Star Wars.

Claim to a certain identikit of epoch-defining pop objects has traditionally been part and parcel to generational identification, but as the chain of generational linearity has been severed or disrupted, a sense of “My Generation” propriety goes out the window with it. The most striking example of this is the Star Wars franchise, which turned 40 years old in 2017. This puts the release of Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi as far from Lucas’s annus mirabilis of 1977 as 1977 was from the release of Think Fast, Mr. Moto, Charlie Chan at the Olympics, and Topper, to name but three franchises of the 1930s whose cachet had faded significantly by the advent of the Carter administration.

The postwar 20th century was a place of Balkanized subcultures; the post-Y2K 21st is defined by centralization, and what used to be called fanboy or nerd culture—the stuff of Ready Player One—now might just be called the culture reigning supreme. DJ George Costanza’s mixes, as his chosen name might suggest, focus on the 1990s—a period poised just on the precipice of Internet ubiquity, in which the concept of the subculture enjoyed its final flourishing. Jacob Ciocci, a great, gonzo video artist and Wightman’s collaborator since before their days in the influential net art collective Paper Rad, addresses the popularity of the ’80s nostalgia-driven Netflix series Stranger Things (2016-) in a 2017 blog post, writing that “This cultural moment (late ’80s/’90s kids culture) is also particularly important to look at now because it was one of the last (and maybe biggest yet to manifest on planet earth) fully formed popular culture moments to exist, without the Internet.” The disappearance of subcultural distinctions leads to what the K-HOLE defined as “Normcore,” a celebration of basic-ness and a new anti-exclusivity which essentially predicts the chain of events that would lead to Balenciaga Crocs at runway shows.

Stranger Things

In times past, a previous generation’s pop culture, subcultures included, would fade from public memory, decaying and in the process providing fecund soil from which that of the following generation’s pop harvest could grow. For those who cared enough to look for them, traces of the earlier work could be found in the sediment, but the object itself had disappeared. In the 21st century, pop culture has shown itself resistant to biodegradability. Everything that was, is and continues to be. Everything, that is, that can be related to the childhoods of the first Internet-acclimated generation—Cline, slam poet laureate of fanboy culture, was born in 1972, and most of Ready Player One’s allusions date from within his life-span, the odd King Kong and Mechagodzilla or 1960s-vintage Batmobile notwithstanding.

The Stacks in Spielberg’s film are imagined as a habitable junkyard of sorts—among the great landfills of recent cinema, along with those of WALL·E (2008) and Isle of Dogs—neglected by a population in thrall to the virtual. The image of the landfill is also an important one within the culture of the Internet, whose essential feature is that of jumbled accumulation. Case in point: the dearly departed, poetically named Dump.fm, an image-sharing site whose junk-heap stream was supplied in real time by an audience of participant amateurs, which breathed its last online in February of 2017, though it’s survived by imitators. In the term “deep dive,” as popularly employed by web archaeologists, one can even detect a certain fragrance of the dumpster.

A trash aesthetic, redeeming the disposables of consumer culture as art, long predates the digitized present—we can point to the entire history of collage, Joseph Cornell’s diorama boxes, and the 1950s found object assemblages of Bruce Conner, made of materials saved from the rubbish bins of San Francisco. Both Cornell and Conner were, along with Canadian director Arthur Lipsett, crucial contributors to another scavenger aesthetic, that of the found-footage collage or compilation film. A uniquely contemporary version of the compilation film—and an embodiment of the dumping ground aesthetic of glut—appears in the series of TV Carnage montage videos, assembled by Derrick Beckles beginning in 1996. These lurid compilation works are something like a fin-de-millennium found-footage equivalent to the globe-trotting Mondo film of the 1960s—though their parade of shocking discoveries were of a distinctly domestic variety, creating ever more ludicrous and grotesque recombinations from the slop and sweepings of workout instruction tapes, direct-to-video movies, and maladroit public access TV, also a key reference for the work of Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim (whose Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! would employ GI Joe PSA auteur Eric Fensler) and their epigones in the Super Deluxe and Adult Swim families, working in the line of the surreal, garish, and ghastly comedy.

Tim And Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!

The TV Carnage compilation tradition has been carried on by Chicago-based group Everything Is Terrible!, who also dabble in conceptual art activities, the most ingenious of these being The Jerry Maguire Video Store, a public display of 15,000 VHS tapes of Cameron Crowe’s 1996 romantic comedy. At present EIT! is attempting to raise half a million dollars via GoFundMe in order to construct a “permanent and safe” pyramid for the tapes, to be erected at an undisclosed location in “the American desert.” There is no small overlap between “anti-humor” and “post-Internet art,” two little-loved descriptors, the latter applied to Web culture–savvy art-world figures like Ryan Trecartin and Cory Arcangel, whose practices brush up against the world of non-narrative or experimental moving-image work, and who both in their own way are in the practice of artistic trash trawling.

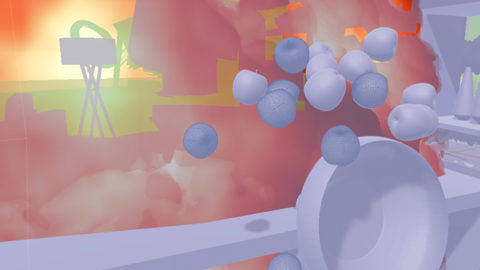

“Jumble” is the first word that springs to mind when viewing a representative Trecartin work like Center Jenny (2013), which depicts a squabbling pack of women who are all different iterations of the same “basic bitch” striving to attain the nirvana of Normcore sameness. Arcangel’s self-described “cinematic feature” Freshbuzz (www.subway.com) (2014) is a catalog of the waste product put out by even the most seemingly innocuous Web presence, documenting an act of Internet excavation in a single hour-long screenshot take that observes the artist scrolling through the website and social media accounts of the Subway fast food chain, previous to their purge of spokes-creep Jared Fogle. Arcangel’s approach is methodical, but a sense of giddy crisis is not unusual, as in Ciocci’s delirious song suite The Urgency (2014); the short video works of Jon Rafman, concerned explicitly with the attrition of the encounter between man and technology; and Rachel Rossin’s eye-of-a-hurricane VR piece The Sky Is a Gap (2017), an inhabitable environment of exploded debris.

In this realm the choice of an analog or digital practice sometimes seems to imply an entire ethos, as traditionalists fight a rearguard action using small gauge film, which today in its scarceness seems to glow anew with intrinsic qualities of warmth and physicality—you’ll almost always find “tactility” and “texture” in writing about shot-on-film work. Through rededication to obsolescent formats, working with film aligns with a host of strategies to avoid the online economy: music-on-cassette labels, for example, or the output of “network fatigue” artists as identified by Pablo Larios. In one respect, at least, the phrase post-Internet effectively describes the game-changing state of affairs ushered in by Web 2.0: even work that turns away from the virtual world is, as a result, defined by that world, to some measure, in its opposition.

Center Jenny

The idea, not unsympathetic, is to take shelter from the coarsening commodification of the Internet in a 21st century Axel’s Castle, so as to contemplate the beauty of the real world—but is the beauty of the real world still out there to discover? For Steven Shaviro, writing in a 2013 piece for e-flux that outlines the theory of “accelerationist aesthetics” as put forth in his book Post Cinematic Affect, opting out isn’t an option in a neoliberal hellscape where “real subsumption leaves no aspect of life uncolonized.” If artists, hemmed in on all sides, can’t escape the horrors of the system and its pop pablum, they can at least exemplify it. “Intensifying the horrors of contemporary capitalism does not lead them to explode,” Shaviro writes, “but it does offer us a kind of satisfaction and relief, by telling us that we have finally hit bottom, finally realized the worst.” Shaviro offers Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor’s Gamer (2009) as an instance of accelerationist cinema, of “works [that] may be critical, but . . . also revel in the sleaze and exploitation that they so eagerly put on display.”

Shaviro’s interest in accelerationist aesthetics is grounded in a desire to find art adequate to the task of embodying the horrors of late capitalism; if I return to the idea of an aesthetic of glut, it’s because it seems better suited to the ambiguous attraction/repulsion represented in much of the work cited here. It’s a loser’s game always to expect uncomplicated criticism and nothing more from true artists, a breed who are consistent only in their susceptibility to hedonism. The subtitle of Ciocci’s The Urgency proclaims the piece “Dedicated to All the People Who Have Had Their Lives Wrecked by Computers, the Internet, or Social Media,” but as is the case with a great many new media or post-Internet or net.art operators, any suggestion of technophobia is tempered by an equal or greater measure of enthrallment, what Ciocci calls his “infinitely confusing relationship [with] consumer-based entertainment” and “obsession with being eaten alive by ‘bad media’”—the artificial, high-fructose, riboflavin-coated kind as celebrated in Ready Player One.

The Promethean gift of the Internet was handed down from on high, bundled in the Utopian language that continues today to be the lingua franca of Silicon Valley, where a seemingly earnest belief continues to persist that the problems of global warming, ethnic cleansing, and mass immigration could be sorted out if only there were only enough Oculus Rift headsets to go around. Because of this, we often fall back on a habit of talking about the world that the Internet has wrought—or is in the process of creating—in terms of Utopia or Dystopia, the opposing poles that define Ready Player One, with its desert of IRL and its plugged-in OASIS.

Like the Internet, like all technology, the OASIS has no inherent morality, and is only as good or as bad as the people pushing the buttons. At the center of Spielberg’s film is a struggle for the control panel, in which a ragtag band of renegade netizens must compete with the interests of the impersonally cruel, highly organized mega-corporation IOI. This being a crowd-pleaser, amateur ardor triumphs over faceless efficiency, while here on Earth, such a definitive triumph is far from sure. What is certain is that technological upheaval has left us surrounded by a glut of accumulated pop effluvia. It is in the very air we breathe and, for a generation of artists, trash is the tool best suited to describing the contemporary condition: the medium is the mess.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.