Killing for a Living

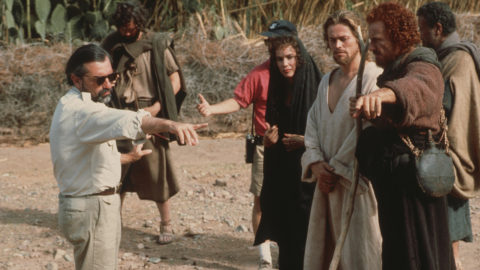

The story follows Frank Sheeran, a hit man for the mafia. He fought in the Second World War, saw a lot of combat, had to do a lot of killing, and that desensitized him, in a way, to [murder]. He meets Russell Bufalino, the top Mafia person in Philadelphia, and little by little, he starts getting more trust from Bufalino and other Mafia people. So they start asking him to do jobs for them. Bufalino introduces him to Jimmy Hoffa, and that’s the beginning of a very tight relationship. So we follow that relationship of basically these three men as the years go by.

There were a few notions that Scorsese mentioned as we were starting to prep the movie. One of them very early on was about wanting to have a feeling of the photographic memory of the past. He mentioned Super 8 or 16mm home movies, and just asked me in the general sense how I thought we could achieve that feeling without literally shooting with grainy, handheld film. So I got more into emulating the still photography look of the different decades, in particular the ’50s, and then the ’60s, and then of course a lot of the story happens in the ’70s. I decided to separate those decades with those looks, emulating those emulsions: Kodachrome in the ’50s, and toward the ’60s we transition to Ektachrome (also saturated in color, but more a blue-green tendency, and the shadow).

Then for the ’70s, I transitioned into a whole different look, which is not still photography: ENR, a process that was developed in Technicolor by Vittorio Storaro, in which the silver is retained on the print of film for motion pictures, and the result is high contrast and desaturation of color. I started applying levels of this ENR look, so that basically the film starts getting drained of color in the later decades. That gives a feel of nostalgia, maybe, for the past, even though the events that are happening are not necessarily the prettiest.

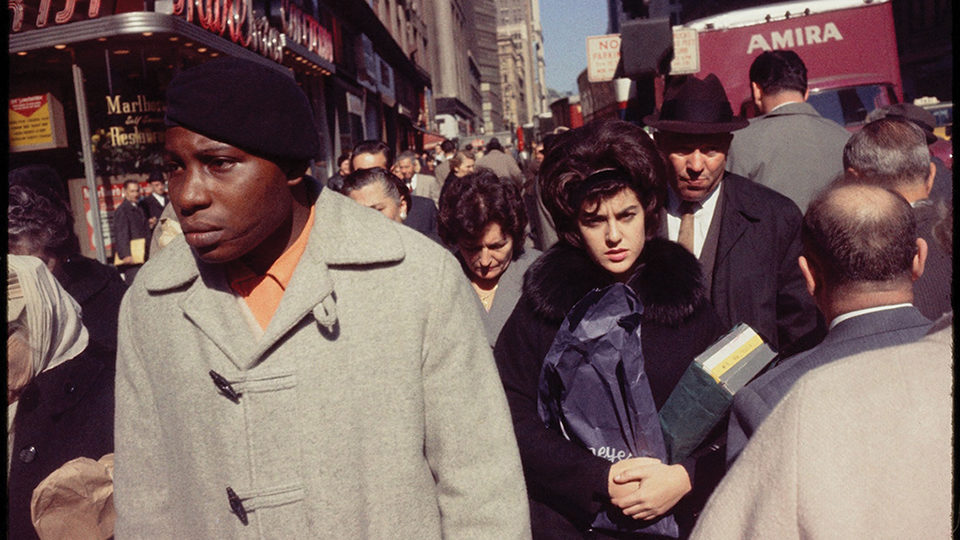

Photo by Garry Winogrand, 1965. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Scorsese is such a cinephile: he did mention movies that I looked at, like Lucky Luciano, just to get a [greater] sense of the era. And we saw newsreel footage, also, of the time and of the events. Recently, as I’m color-timing the movie I’ve been strangely referencing Garry Winogrand: there’s an exhibit of his Kodachrome work in Brooklyn (he usually is known for his black-and-white photography). I used Winogrand a lot as a reference for The Irishman, more for composition and the use of lenses, the wide angle, that sort of thing.

Scorsese talked a lot about how he wanted the job that Frank Sheeran was doing not to feel exciting. He wanted a routine sense to it, and that related mostly to the camerawork. So when we see some of the killings he does, it’s not exciting, it’s not sexy. We filmed it in a relatively straightforward way, where the camera would be perpendicular to the lines, and the camera moves are very simple. It’s a frontal, routine way, almost like “clockwork” (a word Scorsese used). It’s simple—he does this act of violence, and goes on with his life.

–Rodrigo Prieto as told to Nicolas Rapold

Closer Look: The Irishman opens the 57th New York Film Festival on September 27 and debuts in theaters and on Netflix this fall.