Journal: Cannes

If Touch of Evil, as Paul Schrader has suggested, is film noir’s epitaph, Jean Eustache’s La Maman et la putain (The Mother and the Whore) may well turn out to be the last gasp and funeral oration of Nouvelle Vague—the swan song of a genre/school that shatters its assumptions and reconstructs them into something else, a newer model that is sadder but wiser and tinged with more than a trace of nostalgic depression. McCabe & Mrs. Miller, for that matter, may be the Western’s epitaph, or at least one of the prettier flowers to have grown out of Tombstone Gulch. In very different ways, all three films tell us a lot about what growing older feels like, and chide us both for what we are and what we used to be. No doubt for this reason, they tend to irritate people, which is perhaps only just: irritation with the way things are is what mainly appears to motivate them.

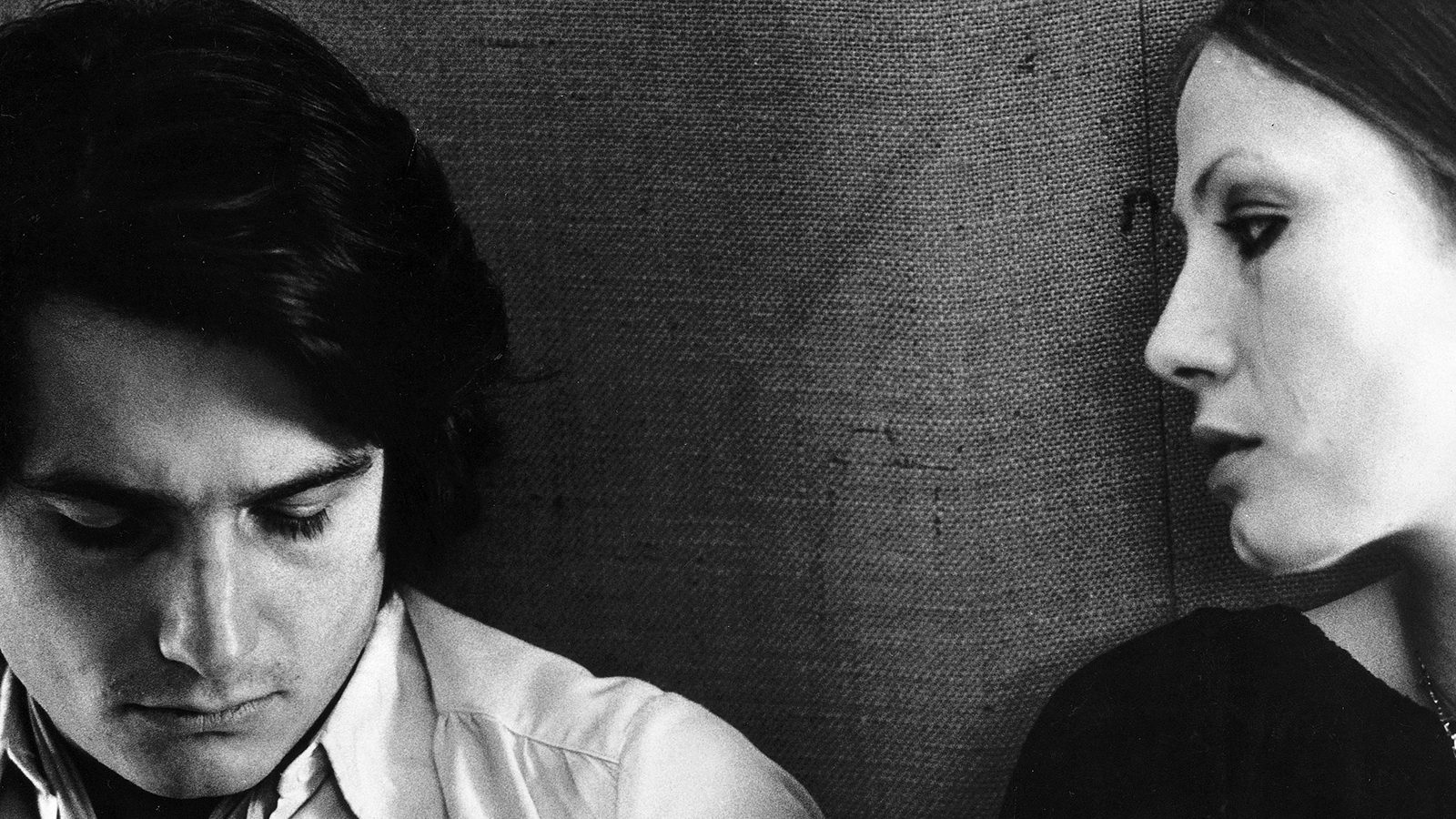

A major reason why La Maman et la putain irritates is that it runs for three and a half hours; and I, who generally feel partial to long films, spent a lot of the first two wondering why Eustache insisted on stretching it out to such a thin consistency. Jean-Pierre Léaud, St. Narcissus of the New Wave, sits endlessly in cafes, restaurants, and other people’s apartments, and talks, talks, talks—ruefully with Isabelle Weingarten (the heroine of Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer), not very much with the older woman he lives with (Bernadette Lafont), and quite a bit with a promiscuous nurse he meets (Françoise Lebrun) and starts sleeping with. Talks with, but mainly talks to—a fairly continuous performance composed of neopoetic rambling and casual posturing, complete with film references reeking of Fifties Cahiers, that has filled many more Léaud films than I care to remember. Some of this is nicely handled—like a scene in a restaurant at a train station, where Léaud explains that Murnau’s films are about transitions—and I didn’t feel compelled to leave; but I did spend a lot of time wondering about why I was staying.

If Truffaut’s slick and entertaining La Nuit américaine (also shown at the festival) begins the process of demythifying some of the old Léaud image, La Maman et la putain surely hammers the point home: for once, the character is finally given enough rope to hang himself—a form of self-exposure that results in his most mature and interesting performance to date.

Like many autobiographical first novels, Eustache’s marathon seems to have a compulsive fidelity to its familiar subject which precludes omitting anything, the sort of blind confidence that can say “I’m going to tell it all” and really mean it. Mutatis mutandis, Whitman, Dreiser, O’Neill, and Stroheim all had some of this conviction, and so, it appears, do Ginsberg, Pynchon, and Cassavetes; Rivette and Eustache provide French models of the same tendency. They can all bore the hell out of you with their obsessions, but sometimes they can also achieve a degree of emotional catharsis that would not be possible without this dogged persistence. La Maman et la putain is one of those rare occasions.

Viewers invariably react to the personal intensity of this film in a very personal way: some call it misogynous, while others complain that the Léaud character is an insufferable bore. In fact, all three leading characters are so fully rounded that one responds to them as variously as one would to real people. As Eustache himself pointed out in his press conference, each has a vocabulary of about fifty words that is endlessly reiterated; these repetitions serve, in effect, as themes for the actors to run variations on. In an explosive, moving soliloquy by Françoise Lebrun—a remarkable newcomer who is the major revelation of the film—so many changes are run on the words baiser (fucking) and putain (whore) that they finally start to mean something. (Although the film’s angle of vision is essentially Léaud’s, the Lebrun and Lafont characters are to my mind a lot more sympathetic and intriguing than he is.) Shot in old-fashioned black and white, and mainly oriented—both physically and spiritually—around the milieu of St.-Germain-des-Prés, La Maman et la putain virtually seals the disillusionments of a decade into one heavy package. Running it as an official selection at the festival was a nice idea.

***

In theory, the Marché du Film is merely one division of the festival out of many (official selections, Directors’ Fortnight, Critics’ Week, etc.); in practice, every film and every person attending is on the marketplace, to purchase or be purchased, and all the rest is journalistic euphemism. It was there, at any rate, that I came across Samuel Fuller’s latest film.

Not all of Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street is peaches and cream, but the beginning is extraordinary—a brilliant burst of action that illustrates the title in lightning flashes—and the mad finale in a weapons room is not far behind. Fuller’s habitual obeisance to the title composer reaches an apogee of sorts in a scene set in the Beethoven Museum, where the heads of both of the leads (Gene Evans, Christa Lang) are cut off by the top of the frame in order to give one of the Master’s pianos a privileged place in the composition. Some of the personal/filmic references get pretty Baroque, too: a clip of Rio Bravo dubbed into German; a snippet from Alphaville to reveal an earlier acting part of Christa Lang, Fuller’s wife (seen as a prostitute servicing Akim Tamiroff); Stepháne Audran doing a guest bit, if I remember correctly, as a lesbian named Mme. Bogdanovich. If this all sounds like a movie freak’s nightmare, I can only confess that Sam seemed to have a whale of a time making this two-bit classic, and I for one had a whale of a time watching it. It may not have production values like Electra Glide in Blue, a conformist crowd pleaser shown in the Grande Salle—a film that aims to outgross the high grossers by synthesizing at least six other “hits,” heartily recommended to all viewers with like temperaments—but by God, it has style. As is customary with Fuller, the acting veers from woodblock hard to awful-ugly (automatically turning every face into a mug shot), the violence is corrosive, the double crosses mutual, the implications perfectly bananas, the imagination fertile. As a modest entry in the Louis Feuillade tradition, this is a minor joy.

***

Two films at the Directors’ Fortnight interested me enough to see them twice: James B. Harris’s Some Call It Loving and Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Who Is Beta? The Harris film in particular was an unusually bold surprise from the producer of some of Kubrick’s best films (The Killing, Paths of Glory) whose only previous directorial effort—The Bedford Incident (1965)—was scarcely better than a more intelligent version of Stanley Kramer.

The plot of Some Call It Loving is deceptively simple: a wealthy jazz musician discovers a young woman (Tisa Farrow) who’s been asleep for seven years in a sleazy carnival exhibit, where male spectators are invited to kiss her (in the hope of awakening her) for the price of a dollar. He purchases this Sleeping Beauty, carries her back to the mansion he inhabits with two other woman, and waits for her to open her eyes. Finally she does, immediately falls in love with him, and soon becomes a part of the erotic fantasies that the two other women continually perform for him. (A black sidekick and admirer played by Richard Pryor serves as another improbable accomplice to his dreams.) But the more that she conforms to his ideally projected images—visions that mainly seem to come out of high school yearbooks—the more dissatisfied he becomes, until he finally puts her back to sleep and returns her to the sideshow, warning the crowd like his carny predecessor that “to wake the Sleeping Beauty, you run the risk of being awakened yourself.”

Working against the langorous melancholy of this solipsistic fable are a lyrical musical score and gliding camera movements that constantly locate the action in a realm of romantic possibility that is never consummated—indeed, the sort of romanticism that exhausts itself before any carnal step is taken—weaving an arabesque around the stasis and void embodied by the dreaming hero, who remains the only real character in the story.

To call this flagrantly unrealistic film “an old-fashioned [movie] with stunt sex superimposed,” or something “only dirty middle-aged men of a certain generation in America could even begin to understand,” as Molly Haskell and Andrew Sarris have done respectively, is to misread it entirely: Harris is concerned with the internal processes and consequences of dreaming more than its objects—with no sex or nudity on the screen, what are we supposed to be ogling?—and taking the ritualistic erotic charades literally is a bit like regarding Plato’s Parable of the Cave as a treatise on spelunking. If traditions are to be invoked, the theme is not very different from that of Four Nights of a Dreamer, and the ending (as conceived and shot) has much in common with that of Lola Montes; but Harris makes the romantic sensibility look a lot more disturbing than either Bresson or Ophuls by detaching the dreams from any humanistic reference: the eye is much colder. In his press conference, Harris indicated that he chose to make his hero a jazz musician in order to characterize a mentality that prefers “playing variations” to “playing the melody,” and jazz, as we know, is a notoriously unfashionable music, perhaps because it occasionally requires its audience to think. But the melody of Some Call It Loving is there to be heard for those who care to listen.

***

Who Is Beta?, subtitled No Violence Between Us, is the third Pereira dos Santos film I’ve seen, and in every way the strangest. Science fiction informed by an anthropological viewpoint, the cryptic plot concerns a post-nuclear civilization composed of two distinct classes, the Contaminated and the Noncontaminated. The Noncontaminated, an elitist minority, live in shelters and devote most of their time to shooting the approaching hordes of the Contaminated, who wear brightly colored togas and advance pretty much like lemmings, offering no form of resistance. The Non-contaminated hero (Frederic de Pasquale) lives in a beautiful shelter designed by himself with an American girl and, later, also a Brazilian girl named Beta; in the evenings, they amuse themselves with a memory machine that he has built, which casts movie images of their past into a screen of smoke. From time to time, he communicates with some “central station” by means of a tiny radio.

The remarkable thing about Pereira dos Santos’s treatment of this multifaceted allegory (which seems to have a lot to do with modern Brazil, fertility myths, consumer society, the political power of sound and image, and affectless violence, among other things) is how ordinary and everyday he makes it all appear. Much like his handling of cannibalism and nudity in How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman and madness in The Alienist, his quiet, ironic comedy effectively desensationalizes the material, allowing us to look and understand before we judge.

When the mysterious Beta decides to leave the shelter, and the hero goes in search for her, this leads us into an adventure story which complicates the plot beyond my powers of paraphrase: it should be noted, however, that a character, who is alternately Beta and another woman who is pregnant, returns to the shelter in the last reel; that the tiny radio is eventually eaten by the hero and his companions (“Let’s eat it like sugar”) when they can’t find any other way of keeping it quiet, while dozens of the Contaminated peer adoringly at them through all the windows and doors of the shelter, in an image worthy of Kafka; that the film concludes with the actress who portrayed the American girl (Noëlle Adam, Chaplin’s granddaughter) flying away on a jet. Endlessly suggestive and always a pleasure to watch, Who Is Beta? stays afloat as a tribal comedy of manners while spiraling off in all sorts of directions at once: like most of the best futuristic fables, it is very abstract and very concrete at the same time.

Philippe Garrel’s Athanor, which reputedly started out as a feature, has been edited down further and further by Garrel until it presently runs—in the version shown at the Fortnight—for the length of an average short: a series of beautifully composed tableaux in which the actors remain virtually motionless. With no apparent narrative continuity remaining, one almost wishes that Garrel would pare this down further to single frames and distribute them as posters.

***

As some of the above comments may indicate, I tended to be more intrigued this year by the films that bewildered and confused me rather than serve up another version of something I’d already seen; from this point of view, Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess and Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again were both exciting events because they wound up defying a lot more conventions than they met—unlike, say, Jean-Marie Straub, who in his History Lesson mainly seemed to be repeating the procedures of Othon—even though the intransigence of each, combined with certain technical problems, often resulted in stretches of pure non-communication.

I wish that I could offer something reasoned and coherent about Teinosuke Kinugasa’s very communicative A Page of Madness—the best by far of the thirty-three features I saw at Cannes this year—but after only one screening on the Marché, I’m afraid I can’t do much more than point and goggle. Made in Japan in 1926—before Kinugasa had a chance to see The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Last Laugh, or La Roue, and in many respects more sophisticated and audacious than all three—this dazzling work was apparently considered a lost film for several decades before the director, now a septuagenarian, recently found a copy that was stashed away in his garden storehouse.

An expressionistic ode to insanity, boldly articulated in swirling movements, pounding rhythms and remarkably graphic compositions, A Page of Madness surfaced in London several months ago, to considerable acclaim and attention (see, for example, the useful comments in John Gillet’s “Japanese Notebook” in the Winter 1972-73 Sight and Sound), but for reasons that continue to elude me, the international press ignored the filmless than a dozen people showed up for the screening—for the sake of staying to the bitter end of Frankenheimer’s dreadful Impossible Object, which was shown an hour earlier. Chacun son gout.