You’ve often said that your approach to writing is that you accumulate material and ideas in notebooks, and find the story through the development of characters. Is that applicable here?

JIM JARMUSCH: Yeah, maybe even more so to this. I mean, this came out of frustration because I had another project that took a long time to write, which means four months. I had written it for specific actors, as I always do, and it was a story for two people and one of them loved it and the other one didn’t really want to do the film, and that threw me for a loop. So then—I don’t know if I want to say I wasted time, but it was a somewhat bigger film for me, maybe $10-15 million, but the people who were interested in financing it started pulling this kind of traditional thing where they were giving me lists of actors that would replace the actor I had written for that would make it possible for them, and they were not actors that I wanted to work with, or that I had imagined. I’m not a studio filmmaker, so it just seemed like, Wow, I’m entering this kind of structure. So I basically got frustrated and put that script away in a drawer.

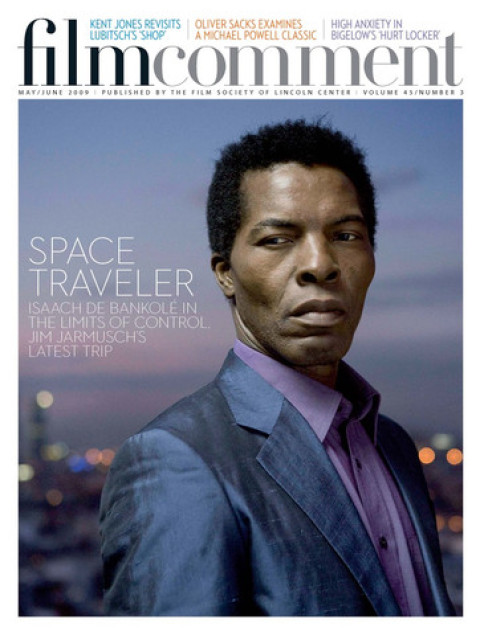

I had a lot of little elements for this film in my head. First of all, Isaach De Bankolé—wanting to write a character for him that was very quiet, possibly criminal, on some kind of mission. Then I had the idea of shooting in Spain for disparate reasons: one was the incredible architecture of Torres Blancas, this building in Madrid from the late Sixties that has almost no right angles in it and it’s very strange. I first encountered it maybe 20 years ago, an old friend of mine, Chema Prado, the head of the cinematheque in Spain now, has had an apartment there for years. And Joe Strummer’s widow, Lucinda, gave me a photograph of this house in the south of Spain, outside of Almería, and said that Joe always said, “We gotta show Jim this house, he’s gonna want to film it.” So I had those elements. Then Paz De La Huerta, who I’d known since she was a teenager—somebody told me, you know, Isaach and Paz are in four films together, some of them student films. And I said, Man, I’m going to use them in a film together then! So that was another element. So that’s always my procedure—having these initial ideas. And I was listening to a lot of music by these bands Boris, Sunn O))), Earth, Sleep—it’s a certain genre of noise-oriented rock with some allusions to metal, but Sunn, for example—if you listen to some of their stuff without knowing what genre it is, you might think you were listening to some avant-garde classical music or electronic-generated feedback.

But anyway, that stuff was floating around in me, so it’s my normal process to have these things and then start drawing details and eventually a plot. But this one I kept very minimal because I wanted it to expand while we were shooting. I wrote the story in Italy over a period of a week or so, and I wrote a 25-page story, and there wasn’t really dialogue in it at all. So I used that and I took that to Focus and said, I want to make a film based on this story, I’m going to expand it as I go; I wanna cast these people. And they were like, Wow, yeah, great… I felt they’d say, Go write a script and come back, but instead they said, No, if that’s how you wanna do it, we’re interested in that. So they financed the film. And Chris Doyle and I had wanted to work together for a long time; we’d made one music video together, but we’d known each other a long time; he was actually going to shoot the other film that fell through, and he even put off certain films for that one, and gave up some things, and then he did the same for this as well because our schedule got moved. So he was very supportive in that way, waiting to work together. And we talked a lot about my little 25-page story; in New York, whenever he’d come through town, we’d spend a week or so just talking, listening to the music, getting general ideas for the images. Then we went to Spain and started getting locations.

So your approach to writing is very free-associative.

I don’t know how other people do it, and I don’t like scripts as a form. I don’t read other people’s scripts because I had a lawsuit against me some few years ago, and I hadn’t read the guy’s script, so scripts are always returned unread. So I don’t read scripts; I only read if a friend of mine asks because they’re going to make a film out of it, they’re not offering it to me. But I hate the form; I just don’t like it. Unless I know the director and their style, and the places they’re gonna shoot, I have a really big problem visualizing scripts. So for me, a script is only a map; it’s a roadmap that is created beforehand that has to grow as we work. So I kind of just emphasized that with this film. I took that further and had less to start with…

Than ever before, it seems to me.

I knew the film wanted from the beginning, because I wanted to let it find itself, and also while working be very aware that anything can change and new ideas will come. So they have to be sifted through or received, and thought about. The problem with this film strategically following that was that our shooting schedule was too short. And that became really exhausting because I have these great actors coming in only for a few days, and I have to get their wardrobe, and rehearse, and write their stuff. And also while having shot a 16-hour day. I wanted to have a longer shoot, but we got backed up against the Easter holiday, which in Spain is a whole week. And so keeping our crew and everything would have gone way over our budget so we worked our asses off to shoot it fast, but also to keep ideas coming. So I just put myself in a kind of suspended state of, Okay, you’re not going to get any sleep for six weeks, you’re gonna have to prepare yourself and work this way. So I spent weekends writing dialogue and stuff, trying to prepare for the next scenes with the actors coming in. Luckily, Chris Doyle is extremely fast and focused while he’s working. So without him, I don’t know how I ever would have shot the film in six and a half weeks or whatever it was; it ended up being about seven, I guess. And you’re moving all around Spain too; it was hard, shooting in train stations and stuff.

The movie has the minimal structure and trappings of a thriller, but it requires a different kind of engagement from the viewer; there’s a different kind of contract being made with the viewer in this movie than in the traditional genre movie. You could compare it to certain Rivette films like Pont du Nord or Paris Belongs to Us.

Out 1 especially. Part of me wanted to make an action film with no action in it, whatever the hell that means. For me the plot, the resolution of the film, the action toward the end is not really of that much interest. It’s only metaphorical somehow.

It’s not cathartic.

No, and it’s not traditional in that it even says, “Revenge is useless,” so it’s not a revenge plot. This sounds very simplistic but to me it’s more about the trip and the kind of trance of the trip for the character than the ending being a kind of…

Payoff.

Yeah. It’s there as a kind of convention, you know? But it’s definitely metaphorical. It’s an accumulative approach in terms of the contract with the audience. It requires them to allow things to accumulate, and in a way, just be passive receptors of the trip he takes.

And the film is also a celebration of cinema in a way that the artifice of cinema is definitely referred to as a positive thing, as something I love. This is not a neo-neo-realism style of film; it’s fantastic in a certain way. I didn’t want to make a film that people had to analyze particularly while watching it. I really wanted to make a film that was kind of like a hallucinogenic in the way that, when you left after having seen it, I hope the audience will look at mundane details in a slightly different way. Maybe it’s only temporary, maybe for only 15 minutes, but I wanted to do something to… I don’t know, just trigger an appreciation for one’s subjective consciousness. I was just thinking the other night that in a way, for me, the poet Neruda is a huge inspiration. All those beautiful odes to mundane objects. I kind of wanted to just build that kind of sense of perception of things through this character and how he sees the world. But he’s on a mission, and that’s another element—I’ve always liked this kind of game structure in things. The title comes from an essay by William Burroughs. And Burroughs, his use of cut-ups, and re-arranging found things, was very interesting to me in the same way that Burroughs was very interested in the I-Ching as a motivator. Or Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategy cards. Or the French poets… Queneau made this book, Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, that has little strips you can move around. All of these things were inspiring, I didn’t realize until we were editing the film that I was using Oblique Strategies all along the way. I was weaving things, in a way.

I had the sense that a lot of how the film was shot was decided on the spot. For instance, the shot early on of Isaach De Bankolé entering that building, shot through this pane of red glass…

Chris and I had been to all those locations, so we had sketched them in our minds, but not making a shot list or anything like that, but just looking at them, familiarizing ourselves, pointing out angles for things that interested us. And then, on the day we’re shooting, there’s action involved, so: Guy walks through door. Well, we figured, we liked that, we liked this, let’s shoot this, let’s shoot that. Sometimes we would shoot a couple versions just to see what we’d like later.

Do you do that a lot? Shot variations to give yourself options, where you had three things you liked but ultimately only needed one of them?

What I tried to do was use all three things when in a previous film I would have chosen one of them. And in this case I would try to edit them together often. So I tried to use some of the variations together, whereas previously I might have just used one shot.

That’s a huge change for you.

And yet the rhythm of the film and the style, I don’t find to be that big a departure.

I thought there were a lot more cuts and set-ups in this film.

Well, I used more set-ups, and did more set-ups, but actually used all of them.

Like four times as many set-ups as the last couple movies.

There were a few scenes where I reduced a few shots that I kind of maybe shouldn’t have. Because I was really into using almost every angle we photographed. So less about variations to choose from, but then in the editing room, I thought, let’s try to use them all.

It’s more prismatic, which goes with the subject too.

And the style of the photography of using reflections and framing things.

Things sort of occluding the frame. I noticed how, particularly in the car sequence coming from the airport, it’s like a Brakhage film.

That was shot by Rain Li, a Chinese cinematographer who worked with Chris on second-unit things… So what I did was actually look for all the damaged pieces of film, or the short ends, or things with flares, or some kind of slight aberration of motion—the things that normally I would throw away. I told the editor Jay Rabinowitz to find all the things with flash frames, with the sun flaring… Let’s pull all those pieces and play with them. So that was also kind of an odd, oblique strategy—okay, use the stuff we would normally throw away. I think when Chris first saw that sequence he was surprised. I didn’t say anything about the editing. I think he was happily surprised. Another example is the very last shot of the film. Chris was taking the camera off his shoulder while it was still rolling to get his hand around it to turn it off. And we had framed the film so carefully throughout. We were going up the escalator, and I saw Chris just throw the frame away, not intentionally, just because he figures it’s the end of the shot… When I saw that end of the footage, I was like, No, no, I want the film to end that way so that we’re kind of just throwing away the very careful aesthetic and compositions we did throughout. The story’s over, it’s a film, it’s a mechanical device, and let’s just kind of break that.

It’s a great last shot.

And Chris liked that. When I edited that in, he wasn’t ready for that. He loves all those kind of things, mistakes, accidents. So I also kind of wanted to please him in a way that helped me in the editing; well, Chris will like it if I use this damaged bit here, you know? I wasn’t sure, I was just imagining, and I think he did. So those were all helpful things in finding the style.

So that embracing of mistakes and chance things that are out of your control isn’t something that I would have associated with your work, especially in the careful compositions and camerawork.

I’m always very open while filming, for example I haven’t used a shot list in my last six films, and I’ve always been very open to things I can’t control, like, Oh, it’s raining but this scene’s not in the rain; well maybe this scene’s better in the rain! So I’ve used those things throughout my work. In recognizing what you can’t control you have to decide, is the thing going to make the film better, even though you didn’t expect it? So I try to incorporate that.

How do you integrate the necessity to control things as a director with being somebody that lets it happen, and accepts, and embraces the unforeseen? This film seems to reconcile those opposites.

Stylistically and visually, it’s gone further that way. However, the dialogue in this film was not improvised on at all by anyone, which is something I like to do. I like to let actors play with the language, and I’ve always let them keep the intention but, if you wanna say it a different way, let’s do that, and then I do a take, and if I want to adjust it I do. In this case, it wasn’t me saying stick to this dialogue, but each actor felt, Well, the dialogue’s very particular so I don’t want to move words or move it around much. So there wasn’t a whole lot of improvisation. Gael maybe improvised a bit because I wanted him to speak in a kind of Mexican Spanish slang; if you’re Mexican, you know that guy is Mexican. The slang he uses, the way he speaks. I don’t speak Mexican slang, so I was like, Stick some things in.

Did that in some way disappoint you?

No, because I wasn’t encouraging it. Once the actors said, this dialogue’s very particular, I started realizing, well, they’re right, it has to be done from the text.

The film’s title and key idea of imagination bring out a fundamental conflict. If the imagination is unlimited, your ability to make art comes down to your ability to control or master the physical world.

But there are also limits to those predetermined limitations. There are limits to how much your imagination can be controlled, as well. Which is also what the film is about for me. Your imagination is not controllable by anyone telling you, Well, this is reality. And now you bump against reality because we can say, well, I don’t like the idea of fossil fuels, and I don’t believe in usury, so I don’t believe in having a credit card, so I don’t believe in this and that… But that’s the structure of this kind of model of so-called reality. So as a filmmaker I can’t not travel in a plane or drive my car or use a credit card, you know? Everything beautiful in human history comes from the imagination, the fact that, well, maybe I could invent a way to do this, or I could imagine living this way. And I think we live in a really interesting period; I almost feel like we’re really on the cusp, we’ve already started a kind of apocalypse of thought because all of these old models that they tell us are reality are all crumbling. The world economic system is a ridiculous system, and it’s falling apart.

It’s a fiction.

It’s a fiction. As is what kind of energy we use. Like this is the only way? That’s ridiculous. If you go back to Nikola Tesla—in 1896 he was able to carry around light bulbs that weren’t plugged into anything. All of this stuff is really perpetrated on us, but our imaginations are more powerful. But all those things are crumbling now. The model that we assume is the ecosystem, the Earth, is no longer valid because they didn’t calculate properly, so that has to be rethought. Even how we exchange things is about to break—I think people are going to start bartering or using other forms of currency. But all this is imposed on us. Why are diamonds valuable? Which is a totally bogus thing. It’s decided by some corporate entity that this substance is valuable. Why is gold more valuable than copper? Because somebody said so. It doesn’t mean anything. So all of these things—but they’re starting to fall now, I think, because things like the human genome and the Internet make all these things start to no longer be viable models anymore. Like invasive medicine. You know 50 years from now, they’re going to think, they cut you open and go inside you! How medieval is that?! They used to burn fossil fuels, and everyone drove a little vehicle burning this shit into the atmosphere! What the hell were they thinking!? I think these things, out of necessity for humans, they either have to crumble or human existence will end.

That brings us back to the imagination, because all those things that you talked about, they come from the imagination too. Science is an imaginative process; there’s really no difference in the end between art and science.

No. I have a beautiful book where some Buddhist lamas talk with theoretical physicists and interrelate. It’s called The Quantum and the Lotus. There are a few books like that. They intertwine all over the place. I always thought of theoretical physicists as poets, in a way. Because they have to imagine this stuff. And I can follow theoretical physics by skipping all the science and math that I can’t follow until it gets to a certain realm where it’s abstract—I can follow that, it’s imagined. They’re positing a possible theoretical answer to something.

And all of that’s kind of in play in the movie. There’s dialogue about quantum mechanics; alongside all kinds of other metaphysical or transcendental ideas or magical thinking. The story about the guitar that remembers every note that’s ever been struck on it.

That came actually from a friend of mine, Rick Kelly, who’s a luthier. He builds guitars and he’s obsessed about the tonal qualities of different wood, and we’re always talking about these things. On a molecular level, he’s always telling me why certain wood will resonate more than another, or why the wood used for Stradivariuses was better than that of other violins at that moment in history, weather conditions, all these things! The scientific qualities of the wood affect a human, emotional thing that comes out of the instrument. So somehow I don’t want to separate them; I want to let them all coexist somehow. I’m hoping people see this film and then they start talking about things like that. I hope it just lets you start making connections. I would love that.

Well, this is a movie that invites many more connections being made than anything else you’ve done before. Your other movies certainly do bring in lots of things, and there are lots of connections to be made in a fairly compact way, but this one is really overflowing.

<p>I think I tried to layer a lot of things in Dead Man, but they were more thematic. This is a little more abstract, and opens up thought that’s a little more abstract.

I think it’s very closely related to Dead Man and Ghost Dog. But the spiritual journey that in those two movies is anchored by a clear, pre-existing belief system and set of values. Here, you kind of cut that loose.

Yeah, I wasn’t using that same metaphor, like life being circular. Although that’s in there somewhere, the way he centers himself using tai-chi.

The film is also the culmination of something a critical look at American culture and values that’s been going on at some level in all of your films, more pointedly from Dead Man onwards. The Bill Murray character’s rant is an elaboration on what that Bush aide said in 2002: reality is wherever we want it to be, reality is what we make it. You must have been thinking of that.

It goes back it that Burroughs essay, though the film doesn’t draw from the essay, which is somewhat outdated now because the media has changed. It says that language is a control mechanism that is used against us. And by people saying “What’s real is what we say is real.” But it’s not pointed at the Bush administration. That’s a great example. But it continues; it’s continuing now. Who is telling us what world economic/financial structure are we trying to repair? Are we trying to prop it up, are we trying to patch up its wounds? It’s something that’s already dead; the structure is the problem. But it’s a huge thing because it has to do with how people are told to live and what is real. I had an interesting revelation recently; I was thinking about museums in the film, and I was realizing, Wow, all those beautiful pieces of art were in a context originally, they were not in a museum. They were part of architecture, they were part of public space. They were part of something that affected your imagination and your visual landscape, and often they came from temples. Christian art or art from mosques. A lot of that stuff was associated with something spiritual. Then I realized, Wow, so that means that museums are the temples of colonialism, because it’s just all the loot that’s been stolen and removed from its context and a value placed on it, often monetarily. I love museums, and I love seeing things like that out of context, but it’s almost like a zoo, looking at animals in a zoo. It’s not where they existed; it’s not where their function was intended to be utilized.

That’s not at play in the use of the museum in this film, though.

It’s just something the film actually made me think of. Well, he sees the artworks out of context, but he can only absorb one at a time. Each time he goes to the museum, he only looks at one single thing.

You don’t storyboard, you don’t have shot lists, but before you start shooting, you must arrive at some conception of an agreed stylistic approach, some ground rules—just through talking with your designer, with your cameraman, with your actors. What was that in this case?

Well, the odd thing is we tweak and hone in on them as we’re going along. So we’re certainly looking for something, but we can’t define it until we’re done shooting. So, for example, the suits Bankolé wears… Those were in my head, and I wanted them in a very specific way. I worked with Bina Daigeler, the wardrobe designer, and she had a Spanish tailor, and I was very particular. We had to find the fabrics, and they’re basically color-coding each act of the film. And I’d go in and say it’s good, but the jackets are a quarter of an inch too short, you know. I was very particular.

How were you able to be particular? How were you able to know that was exactly what you wanted?

It was intuition. I just went in and trusted what I saw and my aesthetic, and said, It’s too short, or the lapels are too big. I just had it in my head. I also got to work with Eugenio Caballero, the great Mexican designer… When I met him, he was coming to New York, I thought, well, Pan’s Labyrinth is a million miles from this, though it was beautifully done. Then I meet the guy, and we were so close aesthetically in so many ways, and he brought all these books and images and how things inspire him, and I just went back to my office and said, I don’t want to meet any other designer. This guy is perfect. And he was, for me. So he was very important. We would talk about everything, every object in the film, and all the locations, the colors of things, the awnings in the café. We changed the color of the umbrellas because we didn’t like the existing ones. We were very conscious of all those details. So all of those are building to a style. And then, of course, with Chris, we’re continually looking for a style. Our only really concrete inspiration, again, in an oblique way, was Point Black, the John Boorman film, simply because he did a lot of beautifully confusing things with the camera and compositionally. But not something we were trying to imitate.

So no ground rules? Nothing, you didn’t have anything when you got to day one.

I knew I didn’t want a handheld look on the film.

Except when there was.

Except for the end, when it breaks down. We wanted some tracking stuff, we wanted some fluid sense of the camera, so there are some nice little moves we did. We just started collecting. Our soundman, Drew Kunin, who I’ve worked with since Stranger Than Paradise—he would laugh whenever we were in interior. Our first shot, he would say, “So we’re going low and wide on this one?” I go, “Yeah, we’re going low and wide, Drew.” He’s like, “That’s what I thought.” Because we really liked the wide lens at a low angle in all our establishing interiors.

But there is handheld intermittently in the movie; the scene where the guy with the violin shows up, suddenly you’re in this side street where it’s totally handheld.

We wanted those to feel a bit different, because it’s the only time we’re leaving our main character. We wanted it to have a different feel; slightly frenetic on the edges, in a way.

So he’s like the anchor.

Yes. So all those little shots in the street, some of them are handheld, some are not. But we did want a different feeling for those. And in the scene with Bill Murray, it starts with static and tracked camera, and then just jumps in all handheld.

There’s also a kind of sense of alternation between formal, symmetrical, centered shots, usually on Bankolé, and off-kilter or cluttered shots or trompe l’oeil effects.

We’re trying to integrate them by sort of checkerboarding them, in a way. Going back and forth between them, but again it was very instinctive rather than plotted out. It was like, well, we just did that; now let’s find an angle that’s a little more, as Chris would say, more dynamic. He used that word a lot. Normally I set up every shot and work with the DP. In this case, I would say to Chris, Here’s what’s happening in the scene. Where would you start it? And I’d see what he would do. And that was good for me because if I didn’t like it I would say, but almost always I loved what he did, because he would really think about it and try to find something more dynamic. So we were finding our style as we went along. Another thing that’s related to that is the idea of variations, because when I wrote this 25-page story it was even more specifically clear that scenes were intended to be variations of something else. Throughout the text, it said maybe 15 times: he looks at such and such as though looking at a painting in a museum. Or the cafés and all the little contact scenes were really just variations, and his traveling are all just variations on another train trip, plane trip, whatever. So that idea of variations informed our style too. Like, let’s do a variation of that shot we did three days ago in this scene that is a different scene but a variation on that scene. When Isaach De Bankolé enters Almería, the last town where he meets Gael—a few days later we were shooting Gael and we had a shot where I said, “Let’s do a variation of the shot with Isaach entering the town,” which was similar but a different street. Things like that. I mean there are so many damn shots in the film I can’t think.

When he looks at a covered painting in the hideout in the mountains toward the end of the film, it’s obviously a variation of having gone in the museums. He looks at a painting that’s covered so he’s only looking at the surface of a white sheet as though it is the painting, in a way. So that’s a kind of obvious one. The last painting he sees is a variation of that covered painting and a variation on the girl on the bed.

A lot of the things that are encountered in the flesh reappear later as representations—and vice versa. The most obvious example being Tilda Swinton: she’s there and then she’s in a movie poster.

Well there are many. There’s the nude painting and then the nude girl. There is the violin painting and then the guy painting the violin.

What are you going for in having that kind of transference from real to represented?

Oh man, I don’t know. I was just trying to layer things in. The idea that the shape of a violin is like the shape of a nude woman’s torso, which is like a guitar, which is then, you know, molecules in the wood and then Youki Kudoh’s character talking about molecules. And then I used this classic polka dot fabric throughout the film in tiny ways, I don’t know if anyone noticed it. I just kept throwing them in. Like you’ll see it when the nude girl grabs the phone, in the bag there’s a scarf that has the same pattern. Or Yuki Kudoh wears that pattern in a suit, or Gael has a cloth tied around his wrist that is of that same pattern. It’s the most classical polka dot print, and I got obsessed with it and did a lot of research about the polka dots coming with the gypsies or the Roma people into Spain in the 14th century in Andalucia. And it’s still very predominant in Spain, particularly in Flamenco culture, which are dominated by Roma gypsies. Anyways, it’s also very molecular.

But doesn’t that kind of recurrence of things kind of reinforce a central idea of: everything is connected.

Yeah that was the intention—reinforcing some recurrence, some kind of image reduced to a basic pattern on cloth.

Tell me about the Flamenco sequence. That’s kind of an interlude in the movie, a moment where the movie sort of stops. I’m interested in why that’s embedded in the film.

Well, yeah, it was developed for the film. I became obsessed with a certain form of Flamenco called Petenera that is a kind of taboo form that people were afraid of for a long time, a lot of bad-luck incidents became associated with it. It is a slow Flamenco, it is not based on rapid foot movements, it is mostly based on the hands; the songs are very slow—some people refer to it as the closest flamenco form to Blues, because the subjects are usually tragic. And it comes from that sort of moment in the 14th century when Spain was Muslim, Christian, and Jewish cultures mixed together. And then I found this one song that’s in the film toward the end interpreted by Carmen Bonares. I had the most amazing and famous Flamenco people in Spain offering help on the film but instead I went towards one of these people who I had seen perform, La Truco, who is not a huge star in Spain, but she was less showbiz—these people are so the real thing. I was so moved by her work I asked to meet her and she was so funny. She teaches a class in what she calls Tai Chi flamenco, and then I told her, That’s so strange, we have Tai Chi in the film. And they were explaining to me why Peteneras is taboo, and I said I wanted to use this one particular song in the film, as I’m using some of its lyrics in the dialogue: “He who thinks he’s bigger than the rest must go to the cemetery, and there he’ll find what life really is, it’s a handful of dirt.” Then we have the recording by Carmen Bonares. Then it’s repeated throughout the film’s dialogue. So first of all I asked them, “How do you feel about doing a Petenera?” They said, “We think it’s a beautiful form of Flamenco that’s been ridiculously pushed in the corner out of superstition, so we would love to do one.” So I gave them the song and we’d meet and they’d show me what they were preparing. It was just beautiful.

So that was another one of those things that I had before shooting—this song that I wanted to weave through the film somehow, so I wrote it into the dialogue, knew I was going to use one version of the song and had them create another version for the film. So that’s how that happened. And it is kind of an odd part of the film where it’s the only time where Isaach’s character smiles—it moves him, you know? And [when they play] live they are incredible. It’s hard not to jump up after they’re done and go crazy because it’s so beautiful and she is amazing. Her father was named El Truco, he was a singer, which means “the trick” not in the prostitution sense but like a magic trick. So I kind of just had that develop to be the center of the Sevilla part of the film.

There are a number of moments, at least three, where the main character is lying on the bed with his eyes open, and the light changes very quickly from nighttime to daytime in real time—not to indicate time passing. What motivated that for you?

That’s hard to answer. Its partly about compressing time or just the ephemeralness of the way the earth and the sun move, which we take for granted, and it was trying to inject a little bit of a dream-like quality into the film’s reality and rhythm. You know, we take our rhythms from the motion of the planet and the universe. So making those artificial somehow, I thought, was poetic for all those reasons and not just one in particular.

The trippy aspect of the film is established in the Brakhage-esque credit sequence with the abstraction of the out-of-focus lights in the distance through the car windshield.

That came again came looking through the footage that you would normally throw out and we found these out-of-focus lights that Chris or Rain had filmed in the tunnel. And I thought, Whoa, these are so beautiful but we can’t leave them too long in the tunnel, because that would throw off the sequence. And the quote from Rimbaud is like a boat being pushed off from a shore in a way, being unmoored, and those lights seemed the right way—and abstract use of film material to make it poetic, they’re not literal images, you don’t know quite what they are. But it wasn’t designed, it was found when we were cutting it.

Another specific moment: when the girl is on the bed with the gun, and Bankolé grabs it from her, you show the action twice, in two cuts. That’s an effect I’ve never seen you do in a movie, and I don’t think it ever happens in this movie again.

Well, I was having trouble finding the rhythm for his taking that gun from her and it was bothering me. And I thought I would like to try a stuttered effect of using pieces from several takes at that moment. And so we played with it and found that it was kind of trippy, which was in keeping with certain ways we were cutting. So I said let’s play with this a little bit and see if I can find a solution that makes that moment striking rather than elongated. When I had each take alone it was too slow, there was something wrong with it. So I was very open to finding an editing way to make it feel right. When we did that, it helped that moment for me, and made it a little trippy, like a blink of the eye. It heightens the moment. And it’s artificial—it’s a movie trick—and I was playing with that.

There’s a similar thing in Ghost Dog: whenever Ghost Dog goes into action, you do a double-image of him to heightens things. And it’s kind of like having an out-of-body experience, all those lap dissolves in the film. Again, something you’d never done before.

Yeah, it’s something I hadn’t done before. And that was Jay Rabinowitz. When I was talking about the musical nature of Ghost Dog—for me all images start with their musical quality—he said, Can I play with some dissolves, even though you like those hard cuts. And I was like, “Yes let’s be open to this and see if it works with the internal feeling of the film and the contact and the character.” And when he started trying a few things here and there I felt they were appropriate.

But you didn’t feel that something like that would be useful in this film?

Yeah, there are no fades, no dissolves—I wanted hard cuts. I wanted to find out how you can make things trippy without playing with the cliché of images melting into one another. Here I was adamant from the beginning. So what can we do by hard cuts and make them musical, poetic, fluid. And we kept that. We wanted to see if we could make things liquid without those actually liquid devices. It was an intuition thing more than “I know that this is what the film wants.”

I have the sense that in this film you’ve gone further in the direction of working from and being led by your unconscious—by setting up a situation where you didn’t have the usual comfort zones to rely on. Working fast with no script in a country where you don’t speak the language, working with a cameraman you don’t have an established routine with.

I wanted very badly to sort of break something—maybe it’s like breaking the idea of a frame I’m always looking through, that the frame could now be rubber, conceptually. I’d think of how I want to translate a scene from my imagination to the screen, and thought maybe I’m too rigid. I’ve always believed that limitations are a strength in a way. Which is why I maybe fell back on the hard-cuts, thinking, Let’s impose something that will make us stronger somehow. And for this film I needed to not have, first of all, a fully fleshed out script.

But you’re absolutely right, that the whole thing was wanting to break something in myself to tap into this intuition, which I’ve been trying to use all along. I’ve always been non-analytical in my films. I’ve always put things in the film without analyzing why. Or what do they mean? Or what am I trying to say? They drew me or pulled me towards them. So this time I wanted to do that even more. And so the structure of making a film and a production based on only 25 pages, ensured that there’s no other way to make it. You’re going to have to follow your instincts. And once you’ve got the cast, the money, the crew, and the locations: the train has left the station. And I had a really good feeling when the train had left the station, though I didn’t have a map of where it was going really. Or a map with only line drawing, sketched outlines. It was a very liberating thing. I can’t analyze if we’re successful but we felt like we were successful in following that instinctual strategy. We were happy to be on the boat that had left the shore and we were gone, you know. So, using the boat metaphor, what’s the weather going to do?, what’s the wind feel like?, should we go in this direction?: we wanted to feel those things. So if a southerly wind came that pushed us north, then that’s the wind that came, you know. Trying to be open to those things, but also being ready to act, ready to follow your intuition without laboring over it. For example, picking the four paintings in the museum—I wanted Spanish painters, paintings that moved me somehow, and paintings that related to the story—but I picked them very fast. There were so many Cubist paintings, and I would say that one is speaking to me.

But doing things fast guarantees that your unconscious will be operative, because there’s no time for you to think.

Yes, time nurtures analysis. Not having time nurtures spontaneity. I’ve always tried to be open and react on the set, and remove myself from things like shot lists. Just another way to push me out in the rowboat without a map. I mean, we did have a map, we did have a structure: structure and form are very interesting to me.

You know where you were going in a loose way.

Here’s a good example for me. Luis Tosar talks about musical instruments and their molecular structure. Tilda Swinton talks about cinema. Youki Kudoh talks about molecular reconfiguration and things possible in science, because we can imagine them. John Hurt talks about the origins of Bohemians and the word “bohemian”—which is kind of a funny thing for me personally because my grandfather was Bohemian, but not in the beret-wearing, bongo-playing sense. Gael talks about hallucinogenic drugs, reflections, your perception of reality and how your consciousness can be altered by things like peyote. And then Bill Murray talks about how your mind is polluted by movies, music, science, Bohemians, and hallucinogenic drugs.

Well, I didn’t have those subjects, those things, when we started shooting. I was starting to imagine what each of these contacts were going to represent, but I wrote them after we were already in Spain, while we were preparing to shoot or already shooting. They all get wrapped up when Bill Murray’s character gives this litany of all the subjects that have already been addressed, but those things weren’t in the script yet, so I was finding those as I went along.

That must have been exhilarating, but also terrifying on a certain level.

Yeah, you don’t know where it comes from. In shooting sequence, the first of those contacts, besides the two guys in the airport that are sending him off, was Luis Tosar. The next one was Tilda. I gotta say that I wrote something for Tilda the night before shooting, I had her for two days only, I gave it to her, we talked about, we filmed it, and it was bad. While I was filming it, I was thinking, “This is not working, and it’s not Tilda’s fault, because she’s amazing. But what I’m putting through her is not right.” I thought, “Fuck, I gotta go home tonight, rewrite this whole scene, come back tomorrow and start it again.” I also made a mistake because I had approved her with red lipstick. I very carefully approved how she looked. On the morning of that first day of shooting, I went there and Tilda and the makeup person had decided they thought the red lipstick was too much. But I really wanted that. I had polaroids from the night before for wardrobe. As we’re filming, not only was what I wrote wrong, her lips were wrong. While I’m filming, I’m thinking “This is not right, I don’t like this, I don’t like this!” That was a bad moment. So I had to just say “We’re coming back tomorrow. I’m gonna rewrite this, Tilda. I don’t like this, I want the red lipstick back. Even the shots approaching we did without the lipstick we have to do over.” So then I go home, stay up all night, rewrite the thing, come back the next day, and film it again. And that threw me for a loop, because I thought, “What if this happens each time? What if I’m just losing it?” Luckily that was the only one where that happened, but it was a good thing I did it again, because I knew on the set it was not gonna be in the film. “I have Tilda, I’m not gonna let her down and have this bad dialogue here.” It was the same subject, but the way it was written was very stilted.

Has that ever happened to you before in another situation where you had an overpowering sense that you’d taken a wrong turn and you had to backtrack?

A few times. It happened once in Dead Man. I was shooting a scene with Johnny and this girl, Mili Avital, and it was terrible. It was just bad. And I knew at the time that it was bad. Some of it came from some of their ideas, and they had no chemistry with each other. So I realized, “I’m gonna make a love scene tomorrow with them, and they’re not gonna be in the same room together. So how am I gonna do that? I’m gonna do it all in close-ups. I got along with both of them. So it was me with Mili giving her a flower, saying things to her, letting her react, and getting moments from her that I loved.

So that was a chemistry issue then?

Yeah, and a staging issue, I think, because I had staged it in a bad way. It was very comical and silly. It was inappropriate, and I knew it while I was shooting it. It was not in the style of the film, but I filmed it. The next day, I brought Johnny in and I told him jokes and made him laugh, and then I took the sound out. So then I had two close-ups to cut, and a scene to make of them. I was happy at the end, because I think I got a very beautiful little scene. That one was an example that I knew at the time, “Wrong! Not working!”

Part of what makes you a successful as opposed to an unsuccessful artist is that you know when it’s wrong, and you know when it’s right. Do you have any sense of where you got that ability to know? It’s not confidence, it’s certainty; it’s clarity.

I don’t know. And I don’t know that I’m always right. It’s just that I think I’m right, and maybe I’m not right, and there are better ways to have done things, but I’m not coming up with them at the time. The possibilities that I come up with, the ones that feel right, speak to me strongly, and the other ones mumble. But again, it’s purely intuitive, and I trust my intuition, even though it will mislead you. It’s not a concrete thing, it’s not scientific. It’s emotion. I try to trust it, and maybe it does mislead me at times, but it’s a strength that I have, so I try to protect it. I have other things that are not strong. I’m not the world’s fastest thinker. I’m not always the most articulate person. I’m not analytical. Those are things I just don’t have. They just aren’t part of me. I would like to have them, but I don’t. I use what I do have that I feel more sure about. I’m also very musical. I don’t just mean literally “musical,” but also how a film moves, how someone walks across the room. I respond to the musicality of things very often. I think in musical terms a lot, because music is something I know I receive.

What you said before about working without nets: the journey Isaach De Bankolé’s character goes on, is a lot like the journey you went on making the movie.

Yes, because he gets his next move each time from the next contact. No one has an overview of his entire game-structure plan, except maybe the Creole guy at the beginning and obviously the Hiam Abbass character knows part of the endgame. But nobody has the whole plan, least of all Isaach’s character. He has to get them as he goes. That’s sort of a Rivettian thing to protect the fact that it’s an impenetrable conspiracy.

And he is a metaphor for you, in a certain way.

He is. He’s seeing variations of imagery, and we’re using variations structurally to make a film out of it. He is definitely on a trip that is imitating ours. Of course, we didn’t film in sequence, which is another crazy thing I had to play with in my head to try to keep track of. Sometimes that’s freeing in a way, but I did shoot in Madrid, then Almería, then Seville, then back in Madrid. So I wasn’t even in the order of the story. But that can be helpful too. He doesn’t know his next move until he gets the information and then he goes there and waits for the next piece. Only for us we weren’t waiting.