The Other Side of Hope

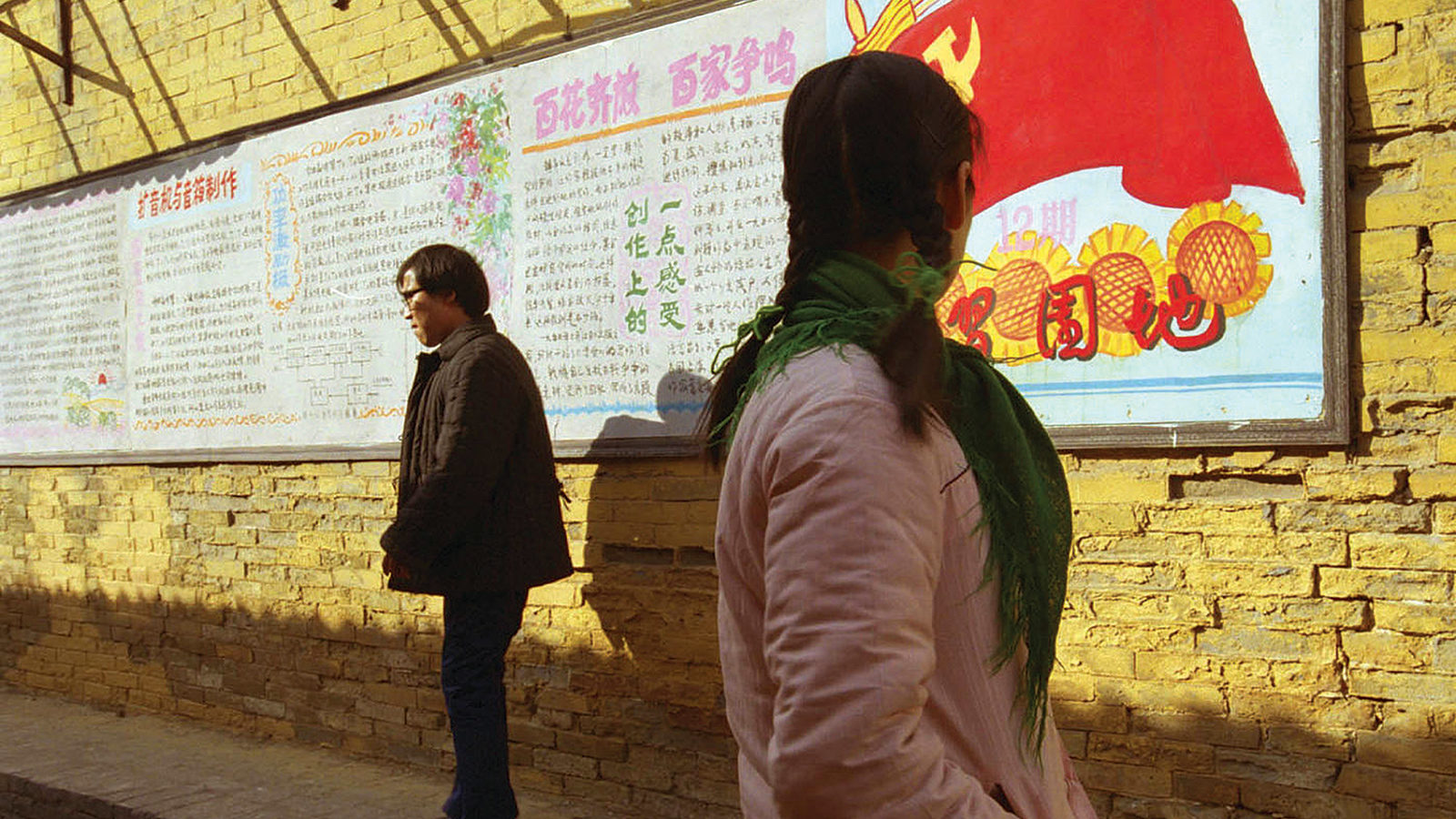

Every grand narrative needs its symbolism. And as far as signifiers go, the wall remains as convenient a metaphor as any for encapsulating China’s past and present, both as they appear in the eyes of foreigners and as they shape-shift within the nation’s own self-image. Of course there’s that famous wall you can spot from outer space, an emblem of former glory that, historians tell us, was actually pretty lousy at keeping out invaders. There’s the digital one that blocks Google, Facebook, and Twitter but that savvy netizens have grown adept at circumventing. And then, on a more local level, there’s the turtle-shaped structure that encircles the old town of Pingyao; the Ming Dynasty relic became one of the most haunting backdrops in modern cinema when Jia Zhangke used it in his 2000 masterpiece, Platform.

For all the small-scale realism of his best-known films, Jia doesn’t shy away from populating the screen with imposing, recognizable landmarks, mining them for drama and making them resonate in unexpected ways. In Platform, the Pingyao wall stands in for a weighty cultural inheritance, one that becomes all but incomprehensible with the inception of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the late 1970s. At the same time, this wall also sets the stage for matters of the heart. In two of the most memorable scenes, a young couple pace back and forth around its parapets, playing hide-and-seek with feelings that have nothing to do with military fortification or ancient civilization. History cuts an impressive figure, but how can it hold its own alongside the push and pull of human emotion, let alone the realities of a society that has spent the better part of a century in the throes of perpetual demolition and reconstruction?

Last October, Pingyao hosted a brand-new festival, launched by Jia, in the shadow of this same wall. Though Jia may not be anyone’s idea of a showman, his decision to establish a boutique film festival here has to qualify as some kind of bold, out-of-the-box gesture. Pingyao has been a popular tourist destination since UNESCO named it a world heritage site in 1997, but its location—an hour’s drive from the main airport in smog-shrouded Shanxi, China’s largest coal producer and Jia’s home province—makes it an unusual hub for international cinephilia. Nevertheless, the conceptual appeal of the Pingyao Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon International Film Festival (PYIFF) was clear: the golden era of Chinese independent cinema had come full circle, finding sanctuary in the old stomping ground of its brightest brand-name auteur, its destiny saddled to his. And as a presiding presence, the wall took on a symbolic life of its own, not just because of the context of Platform but also because of the faceless urban development it was keeping at bay, reminding visitors how uncomfortably the old China coexists with the new.

Jia Zhangke

Once inside the wall, you wonder if you’ve stepped into the kitschy theme park of miniature tourist attractions in Jia’s 2004 film The World: pressed up against the forces of globalization, even a miraculously preserved remnant of history has the look of a simulacrum. For the most part, Pingyao’s ancient city has been spared the Disney-fication visited upon bigger heritage sites like Lijiang, but the main thoroughfare is still marked by an abundance of restaurants, tchotchke sellers, and picturesque inns. It’s in the narrow alleyways where you can still catch glimpses of the secluded small-town life at the heart of Jia’s films: a rickety bicycle making its way down a cobbled pavement, the sun peering out from behind the gently sloping roofs. On opening night, it was surreal to watch this place suddenly go on high alert, with fans and press eager to catch a glimpse of celebrity attendees like Fan Bingbing (who was serving as festival ambassador) and John Woo. One long military phalanx blocked off the route to the venue, another was stationed at its entrance, and security checkpoints were set up within the festival campus, which was built on the old site of a diesel-engine factory.

In the venue a red-carpet event was making its slow progress, giving everyone plenty of time for idle chatter. Why did the headlining film, Feng Xiaogang’s rousing Cultural Revolution melodrama Youth, get its theatrical release pushed back indefinitely while still being allowed to screen here? And why had the festival been delayed just weeks before launching? Certainly the scramble to complete the facilities—a process that, true to China’s reputation for breakneck construction, had begun only a few months earlier—must have hobbled the original plans. Or could it be that the government was actually trying to tamp down attendance by fomenting confusion?

At a press conference for Youth earlier that day, PYIFF artistic director Marco Mueller, the festival impresario who caused a stir in 2016 when he abruptly resigned from the International Film Festival & Awards Macao, refused to be baited, urging the predominantly Chinese press corps to turn their attention to Feng’s cinematic achievements. But as the opening festivities proceeded amid plunging temperatures, in what was being touted as the country’s first state-of-the-art open-air movie venue, aesthetic virtue was not the main concern. A flashy car commercial that Jia had directed played ad nauseam in the pre-show loop. Spotlights swirled as a lineup of entertainers—a pop star, an acoustic singer, a dance group, a rapper—took the stage. Teeth chattered as the obligatory declarations about old meeting new, and East meeting West, were made.

Youth

If you were looking for a reason to scoff at Jia’s idealistic efforts to mount a showcase for independent filmmakers—“under the guidance of Shanxi and Pingyao’s relevant government departments,” as China Daily reported—the variety-show theatrics were grist for the mill. You could also take issue with the fact that a few big-budget commercial movies, like Youth and the nationalistic aerial war epic Sky Hunter, were programmed alongside obscurities in need of championing. Still, it was hard not to marvel at the stamina of a man who, against untold odds, was in the midst of seeing yet another dream to fruition. The phrases on people’s lips were “renaissance man” and “mogul in the making.” Posters of his greatest hits were hanging on the walls of the VIP lounge. The café outside the screening rooms was named after his latest feature, Mountains May Depart. Not far away, in his hometown of Fenyang, were other recent accomplishments: a noodle shop and an art center bearing his name that he opened just last year. The festival was set to premiere a couple of films he had worked on, including poet Han Dong’s black comedy One Night on the Wharf, produced by Jia’s company Xstream Pictures. And as if all this weren’t enough to extend an already formidable legacy, he has a new book coming out and a feature-length project ready to go into production.

None of this has resulted in the kind of domineering or enigmatic persona that often attaches to auteurs this ambitious. In fact, one imagines that the thoughtful, even-keeled disposition that Jia projects in interviews, coupled with his knack for couching media-ready responses in an earnest tone that sounds like candor, has shielded him in a treacherous business. One almost forgets that this is a man who, when he chooses, takes no prisoners. Back in the Aughts, a few years after graduating from the Beijing Film Academy, Jia came out swinging at venerated alum Zhang Yimou, scolding his elder for making money-driven, power-placating spectacles unhinged from reality. Yet not all of Jia’s work has been defined by the pugnaciousness of his early adulthood. And now, in mid-career, it is his turn to raise eyebrows—for courting corporate funders, for feeding Western audiences negative images of his country, and for somehow “compromising” himself to attain government approval. Since the ascent of Chinese cinema as a global phenomenon, a wall has divided those who are tizhinei (“inside the system”) and those who are tizhiwai (“outside the system”). But the purity of such judgments is muddied by an ideological chameleon like Jia, whose stance has never been strictly oppositional but whose success has pushed boundaries well beyond what was previously acceptable.

For several generations, Chinese cinema has been a pressure cooker of suspicion and condemnation. It’s hard to fathom the damage this does to a nation’s cultural life over time, but with the government’s historical stranglehold on the industry it’s also impossible to imagine how things could have been otherwise. One of Jia’s idols, Xie Jin (director of Two Stage Sisters), was denounced as bourgeois during the Cultural Revolution, then managed to rehabilitate his reputation as a hired hand on party propaganda. Most of the key films of the Fifth Generation—from Zhang Yimou’s To Live to Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine—ran afoul of the Central Film Bureau, though that didn’t mean careers were beyond salvaging: Zhang later went on to direct the opening ceremony at the Beijing Olympics. Jia’s first two features were barred from screening publicly, prompting him to find ways of getting all of his subsequent films officially approved for distribution.

One Night on the Wharf

In such a high-stakes environment, where outstanding directors such as Ying Liang, Huang Wenhai, and Pema Tseden have been stalked, intimidated, or pressured into exile, it’s easy to understand why some would regard the mere act of putting a project through official channels as one compromise too many, as a betrayal that legitimizes the very instruments of oppression. And yet it’s also true that without entertaining the possibility of such a compromise, the often devastatingly critical observations of Jia’s films would vanish from the domestic marketplace, left to justify their existence as products for rarefied foreign consumption.

Over at least the past 10 years, Jia has become very familiar with this word compromise. “People always think that interaction with the system is a compromise,” he once said. “I think that’s wrong. Compromise or not, you have to look at the work.” In Pingyao, I spoke with the filmmaker about the major shifts in Chinese cinema over the two decades since his first feature, Xiao Wu, and he voluntarily brought up the issue of censorship, perhaps sensing where the conversation was headed. “At least now there is room for people to negotiate and explain themselves,” he says. It’s a puzzling remark, partly because it doesn’t quite square with recent events. For starters, this past March, the National People’s Congress implemented its first-ever film law, an opaque but extensive network of rules regulating everything from the ideological appropriateness of films to the moral hygiene of their makers.

How good is contemporary Chinese cinema without its rebel streak? The near-total absence of explicit cinematic protest made PYIFF feel like a twilight zone, but it also opened up a wealth of opportunities to discover work outside of the Jia idiom that typically dominates art-film conversation. One of the most exciting titles, Song Pengfei’s visually breathtaking The Taste of Rice Flower, doesn’t aim for state-of-the-nation insight but instead zeroes in on how the rich cultural practices of Yunnan’s Dai community play out in a strained dance between a mother and daughter. This regional specificity was echoed in Hu Yichuan’s Shanxi-produced Depi, a lavish but unpolished drama about a village fool that has a wonderfully antic sense of its own hyper-local appeal. Without the benefit of blunt social criticism, both of these films would easily be overshadowed in a larger, more international lineup, but here they served as revelatory glimpses of all that we’ve been missing out on stateside.

The Taste of Rice Flower

Even with its government-sanctioned selections, PYIFF will have to survive the country’s longstanding wariness of film festivals. On the one hand, the nascent cinephile scene that PYIFF has set out to foster represents a growth opportunity for a country intent on all forms of media domination, whose output is soon expected to soar past 800 movies a year and whose box office revenue exceeded $8 billion this year. According to Mueller, the potential art-house audience in China is estimated at over 50 million, and the emergence of film schools in every province certainly contributed to the festival’s impressive attendance by young locals. On the other hand, festivals and their ethos of free assembly and expression present a challenge to the authorities. Stories of crackdowns abound, including that of the Beijing Independent Film Festival, which was organized by regular Jia collaborator Wang Hongwei and abruptly canceled in 2014. The scope of this suppression has occasionally extended beyond Chinese borders. Jia’s critics are not likely to forget an episode in 2009, when the director withdrew two films—his short Cry Me a River and Emily Tang’s feature Perfect Life, which he produced—from the Melbourne International Film Festival, in protest of a documentary about exiled Uyghur activist Rebiya Kadeer. Authorities had requested that organizers remove the controversial film from the lineup, and when Melbourne refused to budge, Jia publicly announced his decision to step away, citing his discomfort with an event that had become “thoroughly politicized.”

For Jia, that was a rare moment of public embarrassment, prompting those who had been scandalized by Zhang Yimou’s migration to the dark side to contemplate the possible fall of another idol. Here it’s perhaps worth asking why so many artists become a part of our lives and identities, while only a precious few are enlisted to prop up our moral universe. Though he’s never claimed to be a dissident, and has in fact proven allergic to ironclad political positions, Jia still inspires a special kind of hope, particularly among fans in the Chinese world who long to see change in the motherland. His principal genius lies in how he makes that longing palpable, often by interpreting social upheaval through the subtle modulations of sentiment you find in Mando- and Cantopop songs, which he uses liberally and without irony. He does this with the knowledge that, not long ago, those private yearnings were condemned as “decadent.” Indeed, he often recounts a memory of his father implying that, at the height of the Maoist era, a movie like Platform, with its languid evocations of nostalgia and thwarted possibility, would have gotten him labeled as a rightist.

Elements of Jia’s biography have begun to speak almost as loudly as his work. In 2014, he made a short film for Greenpeace called Smog Journeys, an unnerving snapshot of China’s struggle with air pollution. When he announced that the toxic air was driving him out of Beijing and back to Fenyang, he was immediately lambasted by some of his social-media followers. Regardless of the reasons, the tearful return home has always been an irresistible trope for Jia—it’s his ultimate gesture of emancipated sentiment, and a mark of how sincerely he identifies with the young dreamer he once was there. Like Jay-Z paying a visit to his old Brooklyn neighborhood, it makes for a satisfying emotional epiphany. The memory of home weighs heavily on not one but two film portraits of Jia made over the past decade—Damien Ounouri’s Xiao Jia Going Home and Walter Salles’s Jia Zhangke, A Guy from Fenyang—both of which are animated by the director’s fear of losing his connection with his birthplace, and the unspoken conviction that there resides his true self.

Watching these two documentary portraits, you start to understand Jia’s alleged moguldom less as a function of right or wrong politics and more as the result of the same urges that drive his movies. One of the enduring revelations of Xiao Wu and Platform is the rare chance to hear Chinese people speaking on screen in their native accents, moving through spaces they know like the back of their hands. Finally, here was a China that didn’t seem to have originated in a textbook, and yet such a culturally specific breakthrough calls for a native audience to appreciate the difference. If Jia was incensed by the fact that those films couldn’t be viewed on a big screen in China, it’s because the goal had always been to record a walled-off existence and make it visible to those who’ve lived it. With PYIFF, Jia continues to reaffirm his commitment to turning the tides on local exhibition, not only by making smaller films available outside of the country’s major city centers but also by finding a legal framework in which the once-verboten concept of art cinema can exist, with the backing of his world-renowned, time-tested brand. Now that he’s held the spotlight longer than any mainland Chinese filmmaker in history, and now that the ordeal of getting attention for his own work is no longer his main concern, what’s left to do but disrupt again, in his dependably go-for-broke way, the delicate balance of how movies get seen?

Andrew Chan is web editor at The Criterion Collection. He has been contributing to Film Comment since 2008.