Interview: Jean-Luc Godard

The films you’ve made since beginning Histoire(s) du cinéma are more emotional than anything you’ve done before. Each feels like an attempt at reconciliation with cinema.

Yes. I think, if I may say so, it’s like a sentence by Picasso I was once struck by: “I like to paint until the painting refuses me.” I would say that cinema won’t refuse me for a couple more films, a couple more decades, so it’s a reconciliation. Not with what I want, because I don’t know what I want, but with what I want from what I have. And to be more able to not ask for something else, but to do only what you really like, to deal with what you have. It’s a more peaceful attitude. When I’m doing a picture, I’m not angry anymore when it is not well done. Not to be angry that the picture should be this way or against another way, but just to do it your way.

Yet your kind of filmmaking has always represented a counter-cinema.

Today it is in fact against, but I don’t worry about it anymore. When I’m making a big film I don’t say to myself, It’s against this kind of Hollywood picture, this kind of French picture—it’s just the picture I’m doing. I know that I’m definitely the opposition, but it’s a big land, too.

Your whole career, including your work as a critic, can be seen as a process of negotiating, coming to terms with cinema.

I don’t make a distinction between directing and criticism. When I began to look at pictures, that was already part of moviemaking. If I go to see the last Hal Hartley picture, that’s part of making a movie, too. There is no difference. I am part of filmmaking and I must continue to look at what is going on. [With] American picture[s], more or less one every year is enough: they are more or less all the same. But it’s a part of seeing this is the world we are living in.

Is filmmaking a utopian activity for you, in a sense?

The way I wish a movie should be is a utopia, but to make a movie, to make it, is not utopia.

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)

In Germany Year 90 Nine Zero and Histoire(s) du cinéma you regard cinema as a fallen medium.

Yes, that’s my opinion.

What moments defined that fall?

The First World War and the Second World War. World War I was an opportunity for American cinema to beat French cinema, which at the time was more powerful and well known. Pathé, Gaumont, Méliès; Max Linder was a huge star. The French were weak after the war, and it was a way for Americans to disembark in European cinema for the first time. And they had linked to German cinema. Half of Hollywood was filled by [Germans]; Universal was founded by Carl Laemmle.

The Normandy beaches were the second invasion; World War II was a way to take Europe definitively. And now, as you see in politics the way Europe is incapable of doing anything without the OK of the U.S. government, now in the movies America has taken control of the whole planet. So what was democratic in a lot of its ideas disappeared at a time that I will study in my next [Histoire(s) du cinéma]—a very specific time, with the fact of the concentration camp, that it was not shown [by cinema], it wasn’t answered.

What does Schindler’s List mean to you in this context?

It means nothing. Nothing is shown, not even the story of this interesting German, Schindler. The story is not told. It is a mixed cocktail.

You don’t feel that Italian neorealism and the French New Wave represented a recovery after the war?

No, they were the last uprising. What we call avant-garde was in fact arrière-garde [rear guard].

Are you saying that in the Sixties in France your cinema was under American domination?

We didn’t think so, because at the same time we fought very often for some sort of American cinema—a small one. We preferred Samuel Fuller or Budd Boetticher to William Wyler or George Stevens. Our wish, at least Rivette and I, was to be able to make a musical on a big set. It’s still a hope! We said that Hitchcock was a great painter, a great novelist, not just a director of murder stories, so it was more democratic. But it was utopian because we were too young to see what was really going on. I’m saying it today just because I’m probably the only one to ever look like that. I’m using my eyes and ears to study history. Other people use their eyes to read words.

But in embracing certain aspects of American cinema, were you then inviting in the enemy?

Not at all. We were for Hitchcock, but we were also for Shirley Clarke or John Cassavetes or Ed Emshwiller. When I read recently that an American critic wrote that Hélas pour moi looked like a Stan Brakhage picture, I was very pleased. I was friends with Gregory Markopoulos long before I joined Cahiers du cinéma. Later I don’t think his pictures were good, but I remember him and other people who were for a candid cinema. It was democracy. We didn’t realize that the United States doesn’t look like democracy any more than the communist government of Russia.

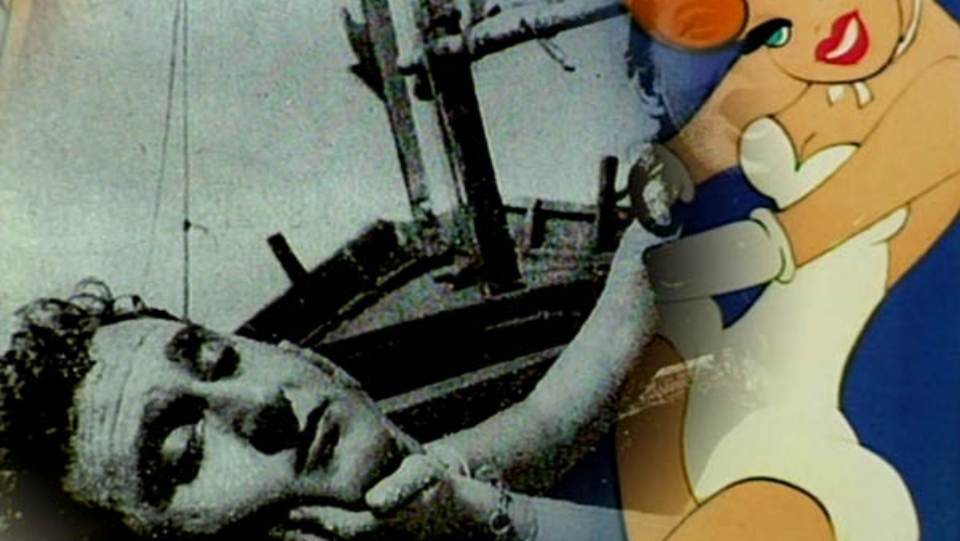

Histoire(s) du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1988–1998)

In the second installment of Histoire(s) du cinéma you say, “Technique sought to reproduce and drain life and identity from life.” What does that mean?

We should analyze the fact that when photography was invented, it could have been color from the very beginning, it was possible. But if it was in black and white for such a long time, it’s not by chance. There should be a moral aspect since in the European, Western world black is the color of mourning. So we were taking the identity of nature out of the painting and killing it in a certain way—

By photographing it in black and white?

Just by photography, by pretending that the photo identity in a passport is the identity of the man—it’s only a picture, not the identity. And then it makes a big change in painting: There was more detail, a more real image of so-called reality. But in fact we were taking out the identity of nature, and then since there was some morality in the culture, it was done in black and white, the color of mourning. And I add that the first Technicolor, and Technicolor, still today, is more or less the color not of real flowers but the flowers on funeral wreaths.

Since your return to cinema in 1979, there has been a renewed emphasis on cinematic beauty. It seems you link this closely to a notion of cinematic mystery.

Yes. Most of the time there is no mystery at all, and no beauty—just makeup. Schindler’s List is a good example of making up reality. It’s Max Factor. It’s color stock described in black and white, because labs can’t afford to make real black and white. Spielberg thinks black and white is more serious than color. Of course you can do a movie in black and white today, but it’s difficult, and black and white is more expensive than color. So he keeps faithful to his system—it’s phony thinking. To him it’s not phony, I think he’s honest to himself, but he’s not very intelligent, so it’s a phony result. I saw a documentary, not a good one, but at least you get the real facts about Schindler. [Spielberg] used this man and this story and all the Jewish tragedy as if it were a big orchestra, to make a stereophonic sound from a simple story.

Well, he doesn’t give you historical fact—

He’s not capable. Hollywood is not capable. In fact, I’m not capable of doing the picture I should be able to do. I’m capable of aiming for it and making part of it, two-thirds or sometimes nine-tenths. Spielberg is not capable of doing Schindler’s List the way a regular director, not a genius but a director like William Wyler—who was able, just after the war, to make The Best Years of Our Lives, which today, when you see it, you’re amazed by the fact that in Hollywood some honest people and good craftsmen were able to reach someone. Cinema as a whole has greater potential than the Wyler picture, but he was 100 percent his potential. Today, that has disappeared. If there was a race, William would do the 100 yards in twelve seconds; Spielberg would do it in two minutes.

One of the main points of Hélas pour moi is that while narrative is vital to the well-being of civilization, it is inadequate as a medium for recording and communicating fact and truth.

I missed just the same in Hélas pour moi, but since I’m a little better than Spielberg, the picture is better. But commercially it’s not as good. I missed the point. The picture arrived at the end completely different from the way it started.

The role of the investigator/narrator, who is reconstituting the narrative by interviewing witnesses, makes me think of Welles’s Mr. Arkadin.

Yes, I remember Mr. Arkadin and I thought of it. [The investigator] was added after half of the editing because the film didn’t hold together. It is a good film but it could have been …. It was not the intention of the movie. In Mr. Arkadin it was the intention. That’s why I say it’s a better picture, because Orson Welles, even if it was only 80 percent his way of doing things that time, in the end it was part of the picture.

JLG/JLG - Self-Portrait in December (Jean-Luc Godard, 1995)

Let’s talk about JLG by JLG.

The correct title is JLG/JLG. There is no “by”—I don’t know why Gaumont put it in. If there is a “by,” it means it’s a study of JLG, of myself by myself and a sort of biography, what one calls in French un examen de conscience, which it is absolutely not. That’s why I say JLG/JLG Self Portrait. A self-portrait has no “me.” It has a meaning only in painting, nowhere else. I was interested to find out if it could exist in [motion] pictures and not only in paintings.

The film presents you in solitude most of the time—is that a reflection of your life or of the self-portrait genre?

I’m very solitary, that’s all—I can’t dismiss it. Inside, I’m very much in communication with a lot of people and things who absolutely don’t know I’m in communication with them. But [on the] outside, yes, that’s my character and that’s the fact of my life, which was too lonely, with difficulties with relations with people. Sometimes I understand people who live like Walden, like Thoreau. But it’s maybe, too, that when I was young I was part of a huge, rich family, with a lot of cousins and uncles. I had so much in my youth that today I think it’s justice that I have less.

Do you see JLG/JLG as a contemplation of mortality? There’s much talk of death.

Of death? No, not at all. At any other time it wouldn’t have been very different. If you have an empty room, I can’t help feeling both guilty and melancholic about the fact that the walls are bare and there is no family, or even a painting of a family up there, because I don’t have a family, just one or two friends. But if I’d put other people in the film, it would become autobiographical and then it’s something different, it’s no longer a self-portrait. A self-portrait is only a face in a mirror basically, or in the camera. Otherwise it’s ridiculous, because then you engage a young actor to play you when you were a child and . . . it’s ridiculous. It can’t be done.

The line “Life is an obstacle in the way of dying, and this film will determine my last judgment”—isn’t that an explicit reflection on death?

Yes…. No, because when I discovered this small photograph of me [the opening image of the film], I wondered why I looked so melancholy already at 6 years. I have a feeling it was not just because my mother gave me a smack; I think it was something deeper. So already I was not happy with the world!

The final words spoken by you are: “I shall live. I have to sacrifice myself by loving so that there will be love in the world.” Are those your own words or a quotation?

I think it’s a quote, but now to me quotes and myself are almost the same. I don’t know who they are from; sometimes I’m using it without knowing.

By repeating a quotation, in a sense you are saying it.

It has to have something to do with me, but I don’t know what exactly. It’s like a color, but with words.

To me, JLG/JLG travels from winter, solitude, and enclosure to emerge into spring, openness, and a renewed sense of the future possibility.

Yes.

JLG/JLG - Self-Portrait in December (Jean-Luc Godard, 1995)

One of the final shots is of an incredibly beautiful landscape in springtime. It seems full of promise of life.

Yes. I think it was a good one to make a metaphor of the world, and then shadows coming. But not meaning sad things—just the end of the day.

Earlier in the film you refer to “childhood landscapes with nobody in them, places where things were filmed.” Does each landscape have a specific personal resonance?

No. I didn’t shoot it myself; a photographer went off and shot them, and I chose from amongst them. It was a Geneva photographer, Yves Pouliquen, who likes to shoot landscapes. Most photographers don’t like to shoot landscapes, they don’t like to obey [i.e., submit—obéir] to the light. This one is not good for lighting, but he is good for going alone as a documentary man. And he doesn’t hesitate to spend three hours just to catch the coming of the shadow of a cloud, and then it brings life into the landscape.

Isn’t that something you would want to do yourself?

Yes, but I was too weak. [Anyway,] I know those places so well, because it’s my neighborhood, that for this particular picture I would have been hesitating too much—this one or this one? Since he was new and was ordered to bring back so many feet of shots, this was a good way to do it. I had a feeling that I was not making the picture completely alone too much, there were several people, not me alone, the so-called genius or anarchist.

A visual motif in JLG/JLG is the school exercise books: first the one you write titles in, then the ones with children’s names on them whose pages are blank, then finally back to your own book, which now also has blank pages. Those blank pages seem like another image of the future, of history still to be written.

Yes.

So this film isn’t a farewell or an epitaph, as some feel. Are you suggesting that your future is the same as a child’s in terms of potential or hopefulness?

I have that feeling, yes. Maybe it’s that when you get old, in one way you feel younger and younger but still being old—young oldness, if I may say so, which is very . . . comforting.

To identify with children?

Yes, but not avoiding the fact that you are older. You still have everything to discover. Usually at their second picture, moviemakers say, “What can I do? I’ve done everything.” Now I say, “I’ve done nothing, everything is to be done.” But I’m not worried about the fact that I won’t have time to do it. I know that although there are a lot of things I never thought could be possible in motion pictures—whatever motion pictures are becoming with electronic technology—just [a shot of] an old bookshelf can say a lot of things.

In the end, you can make a film without leaving your own home.

I did, more or less.

During the opening shot of JLG/JLG, as the camera slowly moves in on the photograph of you as a young boy, the shadow of the camera and the cameraman are very visible.

Just for once, I thought of the audience—a small one, so that it understands that it’s “me and me.” [It’s like with] painters’ self-portraits, painting themselves holding the palette and paintbrush.

There are several shots taken from behind video cameras pointed out windows. Why is the focus of each shot on the image in the camera’s viewfinder rather than the image as a whole?

Well, just to make the audience to think of focusing, the idea of focusing. Making a picture in literature, painting, or music, there is no idea of focusing; pictures focus on the subject.

Similarly, in Hélas pour moi, there’s an extraordinary shot of Rachel (Laurence Masliah) very out of focus in medium long shot; she moves towards the camera and comes into focus in close-up.

Yes, I prefer that. There are pictures in Histoire(s) du cinéma of the shot in La Belle et la bête when Josette Day approaches down the long corridor; Cocteau didn’t make a tracking shot, he put her on a small dolly and advanced her toward the camera. In effect it is the same, but the meaning is not the same. [In the shot in Hélas pour moi] you have the meaning: she’s coming into focus. It’s like somebody submerged coming to the surface, because after all, the screen is a surface. I have to make the audience think of that. It’s like music—not to be definite; don’t pretend to mean this or that. American people like to say, “What do you mean exactly?” I would answer: “I mean, but not exactly.” [Chuckles.]

Hélas pour moi (Jean-Luc Godard, 1993)

In Hélas pour moi on one level you seemed to be exploring the technical vocabulary of cinema: focus, exposure, camera movement, montage, even a zoom out and in, which I think you almost never do—

No. Very seldom.

Was that an intention from the start?

No, that was during the shoot. Because the movie was escaping me, probably I tried to hang on to some things even though they were completely different from what I wasn’t able to do. The grammar was more important than the sentence itself, or the grammar became un souvenir of what the sentences would have been. The sentence wasn’t made, the grammar was made. It’s like a mathematical theorem that has absolutely no success with scientists because there was nothing else to the theorem except pluses, minuses, and equal signs.

But there’s something exciting about seeing a pure affirmation of the grammar of the medium, if only because it appeals to the senses.

Yes, this is the beginning of cinema. The only thing we can do from time to time is to be modest enough to honor this power once more. If you do it in mathematics, it has no meaning. You can’t do it in literature because the sentence and the grammar are so closely linked you can’t cut them apart. But in cinema you can. If you just do a tracking shot or a landscape without anything else…. That’s why I like some underground American films, for example a magnificent picture by Michael Snow, La Région centrale, which is just a long pan. This is a picture, it’s pure cinema.

But those grammatical exercises in Hélas pour moi seem integrated into the “narrative.”

I thought I had a good [script], but it was too soon to shoot it. The first draft I wrote about 100-120 pages, and then we had to shoot three weeks later. So I said to the producer and the star, “It’s not possible, we need three more months or maybe three more years. Are you ready?” And no one was ready, so I did it, because after all, a picture is a picture, it’s like life. We have to eat when we can each day. Then I have to be sure of a certain amount of things, so that’s maybe why unconsciously I tried to hang on to those grammatical cinematic figures.

Until I saw Histoire(s) du cinéma I never felt that the video image could be so beautiful and sensual. You seem to have discovered a way to realize its potential.

I’m using regular Sony equipment [laughs]—it’s just that I’m using it I hope comme un aspirateur [like a brand new vacuum cleaner] in good condition. I like things to be clean and look good; if it’s a bicycle or a car, [it should] look good. Television isn’t well made but you could make magnificent images on television—it is what it is, it does its best. But I think it’s an image a little bit like a painter’s sketch, which can look as good as a great painting.

Your earlier video work was less painterly. Histoire(s) du cinéma is like painting in its texture.

That’s right. It belongs to painting history and it’s pure painting, but cinematic painting-it’s a part of cinema that has been given away by most people. And not commercials. Commercials do paintings, or this Polish videomaker Rybczynski—they’re just commercials, there’s no meaning, it’s decorum. I sometimes prefer commercials because a lot of money is put into those one-minutes and they make things that are impossible in motion pictures because it would be too expensive. But the meaning of them and the sense of them and the aiming of them, to sell this and that—it’s not good. It’s not good to spend a million dollars on 30 seconds on… I don’t know, a General Motors car that is not worth a million dollars.

But I quite agree: it’s painting and the novel. To me, cinema is only my aim, but it’s not possible, because cinema is not painting. To me, cinema is that [points to a painting in an art magazine of several figures in a landscape]. But I like those people [in the painting] to say words, and then there is a drama—but drama painted like that. Not like in a novel. Very often I look at paintings and I say to myself, What is he saying? Those people—what are they thinking of? I remember my very first article was a comparison between a Preminger picture and Impressionist painting. Maybe it’s not possible, but to me it seems possible—it is my cinema. That’s why it’s coming closer and closer to painting.

Now if I put [the painting in the art magazine] in a picture, what should be the image before and what should be the image after? What I like in painting is that it’s a bit out of focus and you don’t care. In cinema you can’t be out of focus, but if you add dialogue, if you show that in pictures, this kind of looking at reality, then between your very focused cinematographic image and the words there is a land that is out of focus, and this out of focus is the real cinema.

Histoire(s) du cinéma

The visual textures of Histoire(s) are layered often in the way that a painting is heavily worked in certain places—with a richness and sensuality.

Yes, sensuality is a good word. The sensuality in painting, which doesn’t exist in novels, is good because each form of expression must have its own forms that the others don’t have, otherwise there would only be one form of expression. From the beginning, pictures belonged to part of each family. Pictures for me are like the bad little last-born of the family of art, the black sheep. But it’s a white sheep—because the screen is white [laughs]. Sensuality is something there isn’t enough of in cinema, which there was more of in the silent era and naturally disappeared with the talkies.

It imprisoned cinema or the image.

Yes, in a way. I try very often to use technology, Dolby for example, to separate the image from the sound, and suddenly when the drama needs it, there they are, both together again.

It’s [clear], especially in American cinema, that you don’t work anymore with the camera through the fact that the camera is [more and more artificial]. I recently saw The Pelican Brief. It’s just commercials. The camera’s moving, but it has nothing to do with the camera movement or stillness or the change of shots of von Stroheim or von Sternberg. There is no meaning, just to pretend we are doing pictures.

You don’t feel that’s another form of sensuality?

No, it’s prostitution.

Another quotation from JLG/JLG: “An image is the creation of the mind by drawing together two different realities; the further apart the realities, the stronger the image.”

That’s an old quotation. There’s almost not a word of my own in JLG/ JLG, but since I was reading and noting them, they became mine.

The film director in Passion says that.

It’s in King Lear, too. It’s a poem by Pierre Reverdy, one of the first dada surrealists, from the time when dada was invented in Zürich in 1921. It expressed very well my opinion that an image is not strong because you see a dead person …. Sometimes, very seldom, just a dead person has an effect. The Vietnam War was stopped not because we saw a lot of dead but because once the American people saw an American student killed in Kent State—only one, not thousands—that was enough. Next morning they were no longer able, [but] it took three or four years and then the bombing of Hanoi.

How would you put that idea into practice, form a certain image out of extreme opposites?

But an image doesn’t exist. This is not an image, it’s a picture. The image is the relation with me looking at it dreaming up a relation at someone else. An image is an association.

Is that where your idea of true montage takes place?

Yes. La vrai mission, the true goal of cinema, was to arrive at a way of elaborating and putting into practice what montage is. But we never got there; many directors believed they had reached it, but they had done other things. Particularly Eisenstein. He was on the way to montage but he didn’t reach it. He wasn’t an editor, he was taker of angles. And because he was so good at taking angles, there was an idea of montage. The three lions of October, the same lion but taken from three different angles, so the lion looks like he’s moving—in fact it was the association of angles that brought montage. Montage is something else, never discovered. It was stopped when talkies came; the talkies used it only in a theatrical way.

When you superimpose the image of Elizabeth Taylor in Place in the Sun with the image of the bodies in the ovens in Histoire(s) du cinéma—that’s montage.

This is historical montage. This is critical work: explaining why the smile of Elizabeth Taylor is such a smile—

Because of the Holocaust—

Because of the Holocaust. And because George Stevens had shot the Holocaust, kept it hidden away for many many years in his cellar, but when he was shooting A Place in the Sun there was kind of both smile and disaster. Even if it’s not an extraordinary film, it’s very intense, and you can’t explain it. None of the other pictures George Stevens made after [were as good]. In The Diary of Anne Frank with Millie Perkins, which is better than Schindler’s List but not a very good picture, he was not able to reach Millie Perkins’s smile the way he does with Elizabeth Taylor.

Throughout Histoire(s) you juxtapose images of great beauty and sublimity with images of horror and atrocity. You seem to be saying that cinema is made between the two.

Yeah, there is an idea of transcendence. When I mixed the newsreel footage of the blindfolded prisoner tied to a post—you know in three minutes he’s going to be shot—I mixed that with An American in Paris, Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron dancing on the Seine. It was unconscious, but after[ward] I said, Yes, I have the right to do that because An American in Paris was probably shot at the same time.

In the first part of Histoire(s) you employ video to achieve remarkable variations on cinematic editing effects—intercut two shots very rapidly, cut to the rhythm of a word processor typing out a sentence. What were you trying to evoke?

It was only to try to meet the images without cutting—very fast superimpositions so that there is only one image but we understand there are two.

It made me think of the 24-frames-per second effect of persistence of vision in film. I thought you were trying—

To elaborate on that, yes.

What about the ultraslow dissolves?

That’s all the old tricks from the beginning of the motion picture business, which [as] the New Wave we were active to destroy—and now with video it’s back, but in a good way.

But there are also transitional effects in Histoire(s) that have no cinematic precedent: for instance, when an image gradually emerges from and eventually erases a preceding image. There are wipes and split-screen effects in motion pictures, but nothing this elaborate. That grammar is uniquely video’s.

Yes, but it’s cinema. Video for me is some kind of department of motion pictures. When you see Histoire(s) du cinéma you don’t have the feeling of the usual video, you have the feeling of pictures.

I’ve seen Histoire(s) as a video projection and also as a tape on TV—

It’s better on TV, if your TV set is properly adjusted and (you have] fairly good stereo equipment. On TV there is no projection. There is a rejection—you are rejected in your armchair or on your bed. In pictures you are projected, but you still have to decide what to be. In TV there is just transmission of something. It’s peculiar to cinema to project, yes.

Again, from Histoire(s) du cinéma, a quote: “The theater is too familiar; the cinema is too unknown.”

Robert Bresson?. . .

Histoire(s) du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1988–1998)

I connect this to your description of cinema as “histoire de la nuit,” story of night, and the image I form from those two phrases is the idea of cinema as a realm of mystery. Why do you think it is that your films from the mid-Eighties on seem to have become increasingly preoccupied with the form of the mystery narrative? Détective, Hail Mary, Nouvelle Vague, Hélas pour moi all revolve around some central, intangible mystery or puzzle.

When you become older, the analysis of the structure is part of the novel itself. It’s the difference between James Joyce’s Ulysses and Erle Stanley Gardner. In Perry Mason the mystery is only the mystery of describing, [whereas with Joyce] the mystery of the writing itself is part of the novel. The observer and the universe are part of the same universe. It’s what science discovered at the beginning of this century, when they say you can’t tell where an atomic particle is. You know where they are, but not their speed; or you know their speed but not their place, because it depends on you. The one who describes is part of the description.

The mysteries you were trying to solve in the Sixties and Seventies were based in secular materialism and had to do with things like desire, ideology, language, and power. Since the Eighties, while your films continue this critical questioning, they seem more preoccupied with eternal mysteries of philosophy and metaphysics.

I think so, and if you can bring the metaphysic through ordinary things, then it’s good. This is a task of the artist. A simple apple by Cézanne is more than a simple apple. Or just a simple apple.

Is that what lies behind your use of nature in Nouvelle Vague and Hélas pour moi?

Yes.

Your use of bright natural light in these two films is unusual—exposure is often set for outside when the camera is in an interior, or for the horizon if it’s an exterior shot. Why such emphasis on high contrast?

Because I see contrast. It’s a way of having two images, far away from each other, one dark and one sunny. I like to face the light, and if you face the light, then contrast appears and then you are able to see the contours . . . which was always the problem of European painting, but more consciously since the Romantics and Delacroix. I like to not have the light in the back, because the light in the back belongs to the projector, the camera must have the light in front like we have ourselves in life. We receive and [afterward] we project.

So you never put artificial lights behind the camera?

Never.

But you still use artificial light?

Only because I have no photographer who is as good as the great photographers of 50 years ago. So I prefer to use artificial light, but not to change things: maybe stronger light to be able to focus if we need to. In my opinion there are almost no more photographers. They have been killed by the way they do TV with light all over the set and all the people with the same fill, no shade, nothing. I use cinematographers who are willing to not use extra lights and try to work mainly on good aperture opening.

In Détective there’s a line: “There’s never any light, only hard lighting.”

Détective was well lit, a good photographer [Bruno Nuytten]. He lit the unknown actors well because they were not afraid if they were not seen. But as soon as the so-called stars like Nathalie Baye or Johnny Hallyday came, then he put artificial light and it was not good. He put light on them because they want to see the speakers on TV. What is the importance of seeing the speakers? We only need to hear what they say.

And you disagreed with that.

Oh, completely [smiles]. There was a fight. But I couldn’t avoid it because it was signed on the contract. It was a compromise. A movie is always a compromise.