Only a filmmaker who possesses the hubris to imagine that art and moral adventure matter could have composed The Portrait of a Lady in the densely telling hues and uncompromising forms Jane Campion has achieved. To start with, the novel’s author has always been rated as a “hard read,” even in the days when reading wasn’t rare. Henry James works every word, every phrase, every description or discourse, so that you must travel his narrative attuned to the minute changes in social/spiritual weather and the moral and psychological reverberations of every bit of small talk. For lack of attention to dangerous undergrowth, a life, or a soul, can be shattered in his “civilized” minefields.

Campion’s Paradise Lost largely manages to recast James’s exquisitely wrought prose, his interior epiphanies and apocalypses, into dialogue, images, and performances that explode in slowest, utterly devastating motion. Like James’s hard reads, this brilliant, difficult film demands close concentration and committed effort on the viewer’s part. The novel’s central metaphors (sun and shadow, house and garden, nature and artifice), resonating dialogue, and actors—aspiring or fallen angels—are authentically animated, without cinematic disguise or distortion, on Campion’s canvas.

Campion chronicles the journeys of women into terra incognita with passionate conviction, making their quests as emblematic of the human condition as any Adam’s. In this, she’s been on the same track as Henry James, who loved to plunge (and vicariously plunge with) his brave Daisy Millers and Isabel Archers into refining—or fatal—“European” experience. Also in the Jamesian tradition, Campion’s heroines may be armed with self-destructive or even killing innocence. In The Piano, Holly Hunter’s silent émigré makes a kind of self-sufficient identity/sexuality of her speaking art. She’s not unaware that her singleminded consecration to her instrument is a come-on, separating the men from the boys, crudely speaking. When she’s brought to earth by Harvey Keitel’s half-Caliban (and symbolically castrated by her jealous husband), she lets her art drown and gets reborn as happy wife and piano-teacher.

An Angel at My Table, Campion’s adaptation of the autobiographies of author Janet Frame, begins by looking down on a fat baby girl lying on her back in the grass. Then we see her toddler’s feet, unsteadily navigating a meadow. Finally we wait—with the camera—for a chubby little girl topped by an explosion of frizzy red hair walking down a long road straight toward us. When Janet Frame arrives, she takes one look into the camera—the world? the future?—and, terrified, runs back the way she came. By the film’s end, when the Australian writer finally makes her way home again, she has bitten deep, often painfully, into life, the imagination, even madness. Campion’s camera puts a period to her journey by rounding the curved side of a very small, snug trailer to look in at Frame at rest and in virtual motion: writing, wombed in warm, golden light.

The hypnotic prelude to Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady begins in darkness, murmurous with the dreaming voices of young girls: “…the best part of a kiss is the moment just before…we become addicted to being intertwined…finding the clearest mirror, the most loyal mirror…when I love, I know he will shine that back to me.” Her camera gazes down into a grove where a sorority of lovely Mirandas lies about in innocent abandon, their bodies curved like silver fish in a sea of grass. Then, in a series of shots in black and white alternating with color, Campion’s hieratic virgins undulate slowly or stand still, always gazing out at us with the provocative serenity of brave new souls. These vestals in modern dress point the way—the film’s title is literally inscribed on the flesh of a woman’s hand—into the film proper, he 19th century pilgrim’s progress of Isabel Archer, New World Candide.

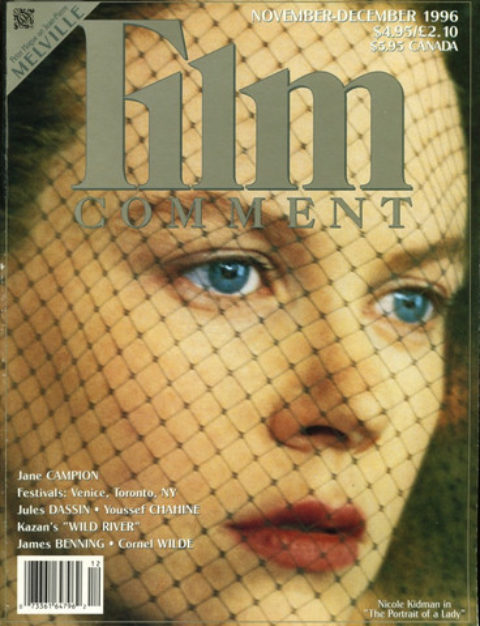

Campion makes us see—with really stunning support from Nicole Kidman—Isabel Archer as both eligible virgin and the bright, double-faced spirit of idealism that humankind perennially projects. Narcissus as much as Diana, she embarks on a quest for her “most loyal mirror”—for wisdom as much as love—through four very different men of the world. Campion shows her as distaff knight, courageously tracking enlightenment, imagining life into art; as chaste voyeur blind to complexity, willing to be deflowered only by dead men; and as an Eve whose free will is illusory, a temporary luxury provided not by god but money.

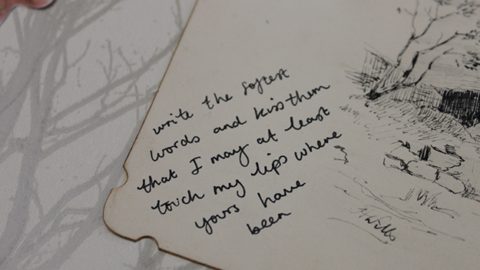

Archer’s odyssey ranges from heaven to hell on earth, from a garden rich with summer’s green-gold promise into blighting experience and back again, to a white and frozen homebase, hard ground to cultivate. But, in perhaps the cruelest sense, nothing happens in The Portrait of a Lady. A woman’s world simply ends, winding down to wasteland: dead zero. Not by accident, as Portrait’s innocent abroad launches into her world tour, she pockets an ominous “ticket,” a scarp of paper on which is written NIHILISM.

Our first portrait of Isabel closes in on her fiercely blue eyes brimming with tears as she turns down a proposal from wealthy Lord Warburton (Richard Grant): “When I’m touched, it’s for life,” the young man vows feelingly. (Touch and the prelude to touching, nearness, verbally and visually implode throughout Portrait, tagging the courage of passionate proximity and stone-cold possession.) This eminently desirable young woman is a guest at Gardencourt, the exquisitely appointed and landscaped English estate that houses her aunt (Shelley Winters, surprisingly good) and uncle (John Gielgud), the Touchetts. Seated among lush green leaves and molten sunlight, red-haired Isabel seems herself a bright flower, one that shrinks from plucking. The curving limb hat embraces Isabel, now so much like an Edenic benison, becomes, by Portrait’s wintry end, a black, no-exit barrier.

Campion’s precisely right to open on Isabel’s laser-blue gaze, for this Eve is all eyes—they’re the loci of her appetite, her avid curiosity: “I want to get a general impression of life…there’s a light that has to dawn,” she tells her uncle, her bright face shining out of a frameful of darkness. It does not yet occur to Isabel, in the ruthless purity of her innocence, that epiphanies may cast terrible shadows.

In these early scenes, Isabel’s heartshaped, flyaway red hair recalls Janet Frame’s unbound coiffure, electrified by a passionate, open imagination. Later, as a member of Gilbert Osmund’s (John Malkovich) coven—with his mistress Madame Merle (Barbara Hershey) and Pansy (Valentina Cervic), the exotic Venus-flytrap Osmund and Merle have crossbred—Isabel’s hair, styled in complete coils, darkens, signifying her new grasp of artifice and the occult. In the barely illuminated airlessness of her Roman home, Isabel is expected to move to a puppetmaster’s design or be still, a rich object d’art useful as investment, décor, or sexual lore.

Referring to a feature of one of Lord Warburton’s many homes, Isabel’s “I adore a moat” are the first words we hear from a Miranda so jealous of her virgin zone she refuses every hands-on surveyor. She flees Warburton, through an arch of greenery, across a vast verdant lawn where the family sips ritual tea. As she passes, her consumptive cousin Ralph Touchett (finely expressed by Martin Donovan) takes her in, following her progress with intense interest. A little dog drags at her flying skirts, and as she catches it, the frame slants slightly so that her shadow, holding up the animal, falls on the green.

Much of Isabel’s itinerary and fate are foreshadowed—literally—in this English Eden, where nature as lush topiary art frames the Touchett’s quietly cultivated way of life. Taking flight from potential largesse—emotional and financial—Isabel imagines herself to be perfectly free to choose where and if she will touch down. Campion closes in on Isabel’s skirts again and again in the film, as incremental refrain, measuring the decline of these beating “wings” from strong purposeful motion into aimless, futile flight.

The little dog that nips at the beautiful dreamer’s heels at Gardencourt is animal life, energy from below that demands attention. Less positively, the dog prefigures Gilbert Osmund, Isabel’s “small,” bestial husband-no-to-be—variously hairy faced, braying ass and snouting pig, who makes Merle “how like a wolf” (though in fact her name’s a poetic form of “blackbird”). Osmund later shockingly humiliates the Eve he’s bell-jarred by deliberately tripping her up as she flees him, keeping her down by stepping on her skirts.

Tilting to frame that momentary stain on Gardencourt’s lawn, Campion’s camera signs the beginning of Isabel’s slow descent into an “unfathomable abyss,” inked in the blackness of Madame Merle’s gloved hand spidering obscenely over Pansy’s stomach; the grounded shadow of a parasol; during Osmund’s subterranean “rape” of Isabel; the line of shade that, by her father’s decree, bars Pansy from a a sunlit garden. Campion will later look down on Roman park studded with trees moated by colorful flowerbeds. AS animated aristos stroll the circular paths, shades of Joseph Cotton and Teresa Wright attend Isabel as she insists she hasn’t “the shadow of a doubt” about the probity of the serpent on her arm.

Caspar Goodwood (Viggo Mortenson) the American admirer who has pursued Isabel to Europe, comes from good adamic stock; sunny open ground, he’s physically passionate and singleminded in his affections. Down from the Touchett estate to London, in the first stage of Isabel’s descent from garden to prison, a fleeing glimpse of a corset hanging suggestively on the back door of our adventurer’s little bed-sitting room sets the tone for Goodwood’s visit. Crowding her into a corner, her least talkative lover braces his arms on the walls that hem her, hardly able to resist touching her. “You don’t fit in,” she cries. She thinks she means in some large social scheme, but it’s the plaint of a virgin, afraid of the pain—and pleasure—of penetration.

Every time Goodwood touches her, at almost ritual intervals throughout Portrait, Isabel recoils as if afraid she’ll catch fire. She can’t take this man in through her eyes, her mind alone; he is too large, too lively for her. As he leaves her room, rebuffed once more, he momentarily holds her chin in his palm. Afterwards, she touches herself in the same way and goes under, as though set off by some posthypnotic suggestion. Her eyes soft and unfocused, she rubs her face against the fringed hanging of her four-poster like a cat in heat. Wojiech Kilar’s sensual music pulses as she trances out in carnal pleasure; Warburton, Touchett, and Goodwood snake about her body, caressing her until, suddenly startled, she shakes the men off and they decorporealize. It’s a scene out of Coppola’s Dracula (scored by Kilar), but even in fantasy, Isabel remains in control and intact.

In James, American Adams transplanted into the hothouse of Europe often grow into passive voyeurs; the refined, sexless inertia of a Ralph Touchett or Gilbert Osmond may signal an aesthetic or diabolical bent. The Gardencourt invalid who registered Isabel’s frantic retreat from Warburton soon plays beneficent angel by “making” his young cousin, that is, by arranging for her to be rich enough to follow the “requirement of her imagination.” Ralph Touchett looks forward, he tells her, to “the thrill of seeing what a young lady does who has refused” an English lord.

Ralph might be James, loosing his engaging young heroine into the world, eager to see where she will take him and his novel. Isabel and her ironically named cousin are Portrait’s truest soulmates, Platonic lovers happy to see and imagine, to apprehend and chew over life as if it were a complex masterpiece to be appreciated by earnest digestion. Their Rear Window symbiosis combines stillness and motion, invalid impotence and unfettered action. Pumping a friend of Isabel’s about his cousin’s treatment of Caspar Goodwood, Ralph inquires hungrily, “Was she cruel?” Campion cuts to a chilling shot of this consumer’s nail clicking on a glass that imprisons a buzzing hornet.

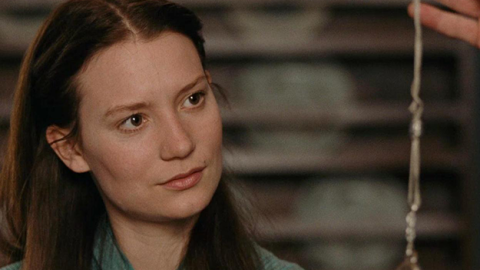

Campion divides her Portrait with a superbly visualized scene between Ralph and Isabel, one that conjures up Buñuel’s Tristana and Belle de Jour, along with Hitchock’s Vertigo. Isabel enters, distractedly, at the bottom of the frame. Inclining up frame-left is a wall of arched, molteny yellow stable doors. Two great ebon horses stand against the slant of golden wood. The effect is surreal, a Buñuelian dream-image hot with sensual simile. But this Belle is blind; she does not blaze until she’s inside the dark stables, her red hair thinly haloed by filtered sun, her face and body shaded blue by tinted windowlight. Isabel has just engaged to marry Gilbert Osmond; her vibrant warmth and color is already contracting toward the cool, hard, still “marble” he will make of her. (Stone and porcelain simulacra amark Isabel’s descent into museumed life: lovers sleeping side by side on sarcaphogi; the chubby marble hand of her dead child; Pansy’s Rosier, verboten suitor, diminished to a little doll hidden harmlessly at her breast.)

In the stables, Ralph Touchett grieves for the bright bird, now tethered by a sterile collector, he has ridden with such vicarious pleasure: “You were not to come down so easily, so soon. It hurts me as if I’d fallen myself.” Isabel’s been his Madeleine, an ideal he can cherish and pursue in his imagination; like Hitchock’s Scotty in Vertigo, Ralph doesn’t want to “touchett,” has no taste for a flawed woman of flesh and blood. A vampire of small but fastidious appetite, he has “made” he Eve for something finer than Psmond’s debasement. As Isabel pleads her case against his “false idea,” Ralph and the camera recede from her. She grows smaller in our eyes, as though her image has been released from his focus, to fall away into a void.

Their reunion comes in the penultimate moments of the film, in Portrait’s single scene of something like sexual consummation. The woman we’ve seen only in postures of sexual passivity or flight climbs into bed with the dying Ralph, frantically caressing and kissing a body already going cold. Their climax is his death, signaled by his hand falling uselessly away from her cheek. As he passes, he admonishes her to keep him in her heart—“I’ll be nearer than I’ve ever been.” (In a preceding, twinning scene, Osmond has come at Isabel as she beats her forehead against a door in despair, brutally pinning her with his body and firmly holder her valuable face from harm: “You are nearer to me and I am nearer to you than ever,” gloats her curator.) In death, Ralph Touchett’s spirit finally enters his beloved’s body in perfect Platonic possession.

From the moment at Gardencourt where Madame Merle sirens Isabel down to her with voluptuous Chopin, images of the young woman who puts such arrogant faith in her islanded identity begin to be doubled, distorted, and dissolved. In her Dantean journey, Isabel’s eyes are opened to her own self-delusions, and to the ugly, convoluted reality behind the “vivid images” she has made of Merle and Osmond.

At the start of Campion’s superb concatenation of horror movie, fairly tale, and re-fashioning of Eve’s mythic Fall, Isabel winds down the stairs of an ancient Roman villa to fetch up in a round subterranean chamber—half mausoleum, half-museum. Set an intervals in this strange room’s ceiling are grilled openings; weak light falls through air dense with old debris, so that barred rectangles punctuate Isabel’s path. Osmond materializes out of the shadows, twirling the parasol she’s left behind. It snaps with unpleasant papery sounds, like the rushing of bats, and he uses it like Mesmer’s hypnotic wheel. The two circle each other, like wary animals maneuvering for better ground, but Isabel’s eyes are locked on his. We’ve seen him work Madame Merle with the most expert hand—“Every now and then I’m touched,” he mocks his earlier conquest as he brutally disengages: Isabel hasn’t a prayer against his snaky intensity. Much later, even as he lashes her with hateful verbal contempt, Isabel leans helplessly in toward his mouth, her eyes “stupefied” with longing.1

As Osmond declares the precise nature of his love—“I offer nothing”—Campion’s camera rushes toward the couple around a curve of wall, past a skull set in old stone. The motion takes your breath away: something like death has passed. The frame tilts to show the shadow of Isabel’s parasol at the lovers’ feet. Osmond seals their unholy bargain with a Judas kiss, swallowing her mouth with a prostitute’s practiced, perfectly timed sensuality—and slides away into the dark. No Miltonic Satan vital with glamour and active evil, Isabel’s ravisher is a lesser devil, a cold collector of fortunes. He has seduced her into a world of pimps and promoters, where manipulation of bodies and souls is his vulgar art.

“I’d give a good deal to be your age again…my dreams were so great…the best part is gone…and for nothing,” confides Madame Merle, the dark sister who has precede Isabel into Gilbert Osmond’s soul-killing embrace. Nothing, out of James by way of Campion, is arrived through the profoundest of passions, an awful violence practiced as perfectly deliberate, often quite public atrocity. In Portrait’s last act, Campion frames Gardencourt in longshot, its beautiful stonework and ivy bleakly rimed in ice, as old Aunt Touchett creaks her way across the snowy lawn, clutching her walker. “Is there really no hope?” Isabel pleads, referring to Ralph’s illness. With grating, indifferent finality, Shelly Winters’s voice speaks a wider epitaph: “None whatsoever. There has never been.”

I haven’t said enough about the character of Madame Merle, played magnificently by that peerless Magdalene, Barbara Hershey. As the dark lady of Portrait, she is a truly tragic figure, because she has far more self-awareness and a larger vision than Isabel may ever attain—she chooses sin with her eyes open. Two images from the film, two sides of Merle: In the first, she and Isabel walk along a series of pedestals displaying classically monumental human parts in marble—a huge hand here, a gigantic foot there. Merle sits down in front of an heroic male torso, its genitalia backing her in the frame—as she unmasks for Isabel, confessing her role as procuress and trying to cozen Osmond’s wife into pandering for Madame Merle’s own daughter.

Later, at the dim convent where Osmond has locked Pansy up for being insufficiently commercial, Campion’s camera passes Isabel’s face in closeup, left of frame, to focus in on Madame Merle, who holds a little doll wrapped in waxed paper. Her glib social spiel, about paying a call on the lonely Pansy, stutters to a halt with her nearly whispered “a little dismal”—apt epigraph for her life and her child. This mater dolorosa is backed by a crucified Christ, painted on the wall ehind her, but Isabel can’t see that. Even in the rain outside, when a bedraggled Merle tries to touch her with “I know you are very unhappy, but I more so,” our unforgiving fundamentalist slides her carriage window shut between them, effectively making nothing of the woman who is perhaps her clearest mirror.

At film’s end, Campion reprises the circling dance in Osmond’s underground chamber, this time with Isabel and Caspar Goodwood, on the very site—now a wintry wasteland—where, as a green girl, she refused Warburton. But as the passionate Goodwood holds his upraised hands to either side of her face—as though afraid to catch hold of her—Isabel literally pants with fear, rounding against his offer of earthly happiness like a trapped animal. “Why go through this ghastly form?” her good angel cries out, referring to her marriage. “To get away from you,” comes her terrible, perverse reply.

Fleeing Goodwood, Isabel follows her earlier route, but now Gardencourt’s grounds are cold and unpromising. The whole weight of Portrait has slanted slowly, inexorably from summer down through seasons of dismal rain into this wintry whiteout, scrawled with the meaningless calligraphy of dead branches. We watch her dark skirts flash over the snow, as though Ralph Touchett’s once high-flying soul knew what significant South she was heading—but her advancement is herky-jerky, slowed by step-printing. Through the manor’s windows, we can see a warm haven of golden candlelight, the color of home in the final shot of An Angel at My Table. In closeup, Isabel’s hand turns on the doorknob. Then, her back to shelter, bleak landscape before her, our bright angel simply runs down, freeze-framed like some lost Galatea. In Portrait’s brave, hard-won ending, Campion’s eve—neither home nor exiled, but pinned in some deadly zone between—gazes out at nothing.

By means of a radical stylistic trope, Campion makes us see that the nature of Isabel’s stupefaction is sexual, moral, and aesthetic. The primitively shot and imagined silent movie—“My Journey”—that follows hard upon Osmond’s seduction is equal, lurid parts Son of the Sheik and Hitchock’s Spellbound, with a little Caligari thrown in for good measure. Jerkily, it segues from the comic, speeded-up motion of Isabel and her friend Henrietta sliding from side to side on the deck of a rocking ship; to Isabel costumed and veiled in Bedouin garb courtesy of a studio wardrobe department, abroad in exotic locales more back-projected than real; through the plateful of Daliesque beans that open like mouth or vaginas to groan Osmond’s “I love you absolutely”; to a climatic plunge down into feverdream and final swoon in sheikland. Flashing on her own eyes and mouth, the bearded orifice of her demon lover and his hand splayed on her naked stomach (as she’s seen Merle’s brand Pansy’s front), Isabel finally falls, naked, into the whirling wheel of a slideshow hypnotist. Is this Osmondian projection the “light that has to dawn” so anticipated by Isabel in the greenhouse of her imagination?