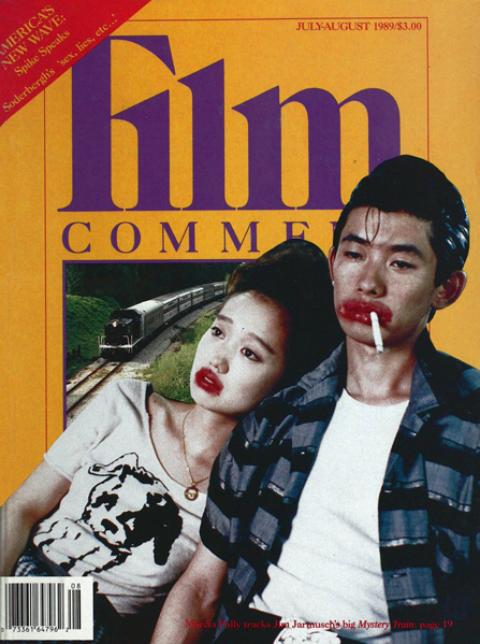

Interview: Spike Lee

Spike Lee will be honored by Film at Lincoln Center at the 46th Chaplin Award Gala.

1989 a number, another summer! Get down…

While the black man’s sweatin’

In the rhythm I’m rollin’Got to give us what we want!

Got to give us what we need!Our freedom of speech is freedom of death

We got to fight the powers that be….From the heart it’s a start a work of art

To revolutionize make a change…We are the same, no we’re not the same

’Cause we don’t know the game….I’m hyped, plus I’m amped

Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stampSample a book that you look and find

Nothin’ but rednecks

For 400 years if you check….What we got to say, power to the people, no delay,

Make everybody see, in order to fight the powers that be….– “Fight the Power” by Public Enemy,

[Radio Raheem’s theme in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing]

It’s the hottest day of summer in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, where the only thing hotter are people’s tempers and a ghetto blaster not only rocks the house but burns it down. While Spike Lee’s previous films looked at the under- and crosscurrents of male/female and light/dark-skinned black interactions, in his third feature, Do the Right Thing, Lee takes a magnifying glass-under-a-hot-sun look at black/white relations and the result—no surprise—is fire.

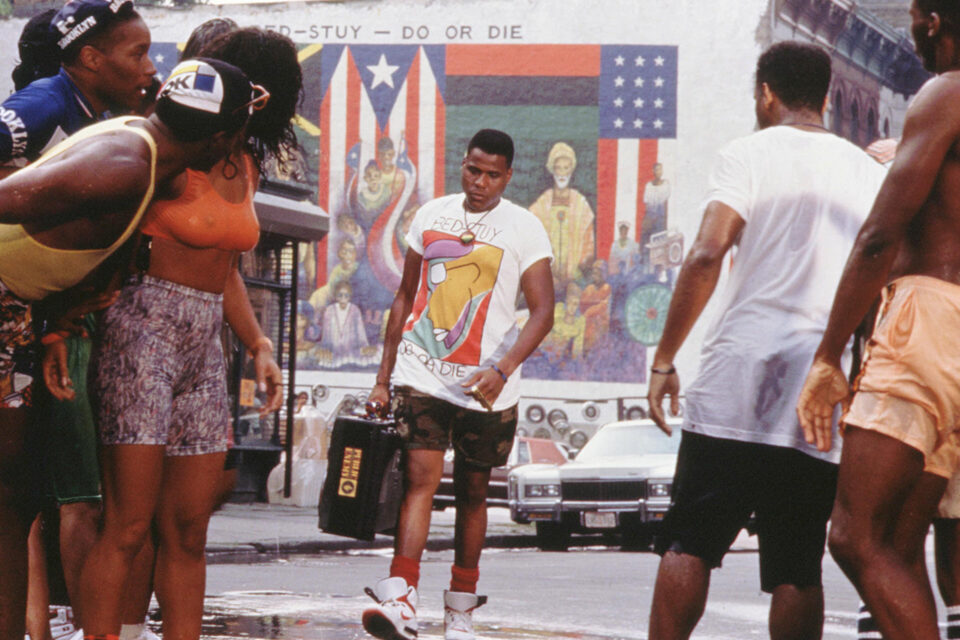

Do the Right Thing stars Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Danny Aiello, John Turturro, Richard Edson, and Lee veterans Joie Lee, Bill Nunn; Sam Jackson and Giancarlo Esposito, along with newcomer Rosie Perez. It was shot in Bed-Stuy using an almost all-black crew (a rarity in the film industry) during a record breaking heatwave.

To pave way for the production, Lee rejected the usual police surveillance from the Mayor’s Office of Motion Pictures and instead installed members of the Fruit of Islam. With them, he also cleared the block of three crack houses. Sets were reconstructed from gutted buildings; behind the film’s Korean fruit stand stood an empty shell. A pizza parlor was erected , murals painted, the street cleaned up, a block party thrown and the shoot was under way. The Antioch Baptist Church served as canteen, where lunch on some days consisted of ribs and assorted Louisiana hot sauces.

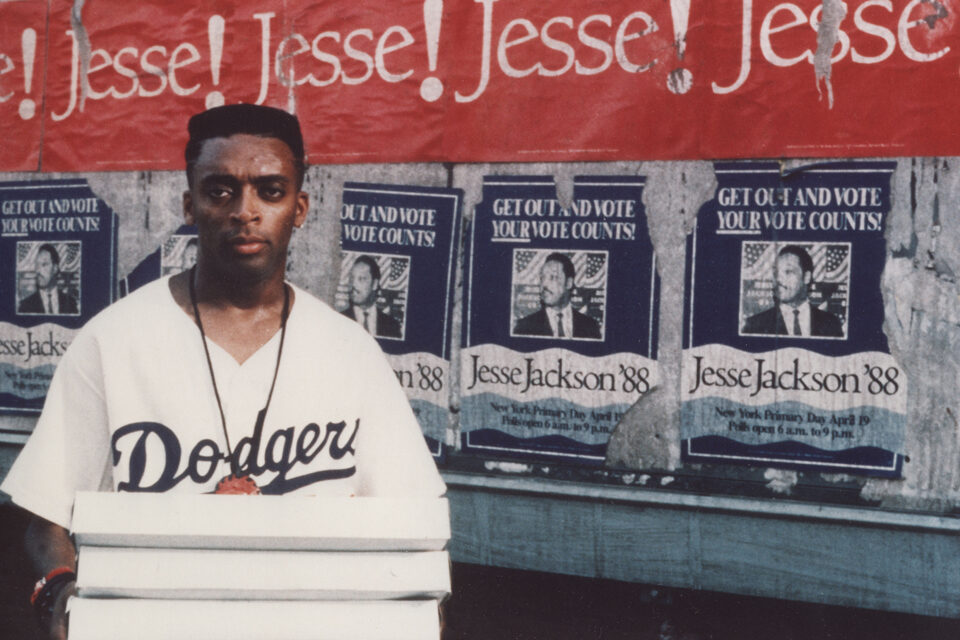

For his role as Mookie, the meandering young black man who is the film’s pivotal character, and who cares less about his girlfriend and young son than getting paid, Lee donned a fade-out flat top and a gold tooth. Cinematographer Ernest Dickerson once again stood loyally behind the lens while the director’s brother, David Lee, shot more of the enigmatic stills we saw in Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It.

Bill Nunn in Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

Lee’s film comes at a time when New York City is a racial tinderbox. The alleged black gang rape of a white Wall Street woman this April in Central Park angers whites, smears blacks, and triggers Donald Trump to take out a full-page ad in The New York Times calling for reinstatement of the death penalty (yet there was no such out cry when Michael Stewart and Eleanor Bumpurs—blacks to whom Lee dedicates his film—died at the hands of NYC police in separate controversial incidents). The Amsterdam News, favored by a black readership, likened the handling of the Central Park rape to the Scottsboro boys, who were falsely convicted and nearly executed for the rape of a white woman in Alabama 50 years ago. One month later, after a 25-year-old black man died in police custody, one black woman told The New York Times, “This is crazy. There’s going to be a riot. Somebody is going to get killed and it’ll probably be us.”

Do the Right Thing takes up the message. Nobody wins when oppressive heat and Raheem’s radio causes a meltdown in Sal’s Famous Pizzeria. What bubbles up is not mozzarella but the bad feelings hidden beneath. The film, which explores the black underclass, ends with two quotes, the first by Dr. Martin Luther King in favor of non-violence, stating, “The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind,” countered by Malcolm X’s “I am not against violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.” It is on this quote that the film closes.

Lee is no stranger to controversy. The MPAA rated She’s Gotta Have It with an X—later reduced to R after it was recut—because Lee included a lovemaking scene with nude black bodies. In School Daze, Lee broke the conspiracy of silence about prejudice between light- and dark-skinned blacks in his depiction of an all-black college campus during homecoming. School Daze also probes blacks’ attitudes toward apartheid-income from South Africa helps keep the school running. And in one poignant scene Lee clashes Africa-identifying co-eds with their Jheri-Curled, shower-capped, local “brothers,” who spout animosity like ketchup: “We’re not your brothers. How come you college motherfuckers think you run everything? You come into our town year after year and take over. We were born here, been here, will be here all of our lives, and can’t find work ’cause of you.”

School Daze was criticized by fellow blacks who did not want long-hidden dirty laundry on view for white eyes. But as always, Lee’s films are topical. A case before the Atlanta Federal Court highlights the heretofore unmentionable: a woman is suing her former employer, alleging discrimination based on skin color. Both the woman and her employer are black; the plaintiff, however, is light-skinned.

Do the Right Thing, like Lee’s other films, is a black insider’s perspective on the contradictions and celebrations of African-American life. But Lee’s talent lies in creating characters that transcend race and economic status and speak to us all. His Bed-Stuy comes alive with neighborhood people we know: Mother Sister (Dee), matron of the block; Da Mayor (Davis), block philosopher; Sweet Dick Willy (Robin Harris), Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison) and M.L. (Paul Benjamin), the Greek-chorus triumvirate who seek shelter from the sun in beer and be neath a beach umbrella; and even the Puerto Rican helado “Icee” man carting his big block of ice and syrup bottles. It is a block where English intermingles with Spanish, where salsa meets Raheem’s rap and the air is radio-active with Señor Love Daddy’s We-Love show, as he does “the nasty to ya ears” with “da platters dat matter,” with black music ranging from rap and juju to reggae and soul—a block where music is a main character.

Nor does this film shy from hot topics within the community. The triumvirate express anger and jealousy over the Koreans’ ability to establish a successful business in their neighborhood: “Either them Korean motherfuckers are geniuses or you black asses are just plain dumb!” M. L. declares. It is also where, in a hilarious but biting scene, “You dago, wop, garlic-breath, pizza-slinging Vic Damone” is countered by “You gold-teeth, gold chain-wearing, fried-chicken-and-biscuit-eatin’ monkey”; where “You slanty-eyed, me-no-speak-American, Korean kickboxing, son-of-a-bitch,” is met by “You Goya bean-eating, 15 in-a-car, 30 in-an-apartment, meda-meda, Puerto Rican cocksucker” and “It’s cheap, I gotta good price for you, B’nai Brith, Jew asshole!” It is where the battery-powered message carrier Radio Raheem (Nunn) blasts the word: “Fight the Power,” and rules—almost to the end.

Lee’s films differ not only in their black perspective—in an industry where few blacks have a voice—but also in their ability to look at both sides of the coin at once. As in real life, his characters are neither all good nor all bad. And therein lies their—and Lee’s-power: the minute he establishes our identification with a character, Lee turns him inside out to reveal the dark side in us all.

Lee’s films are unmistakably Spike: direct, outspoken, no-holds-barred, tell it like it is, pointed and hard-hitting. He approaches his subject matter without hesitation, earning him a reputation as both audacious and arrogant. Do the Right Thing is not only an assertion of black life but, importantly, of filmmaking. It strikes you with the speed, color and style of graffiti: an urban, in-your-face declaration.

Lee’s production company, Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks, is young and black and located in the heart of Brooklyn, amidst Jamaican patty and spice parlors and other black-owned businesses. Nearby, Lee runs film workshops for minimal fees for those who can’t afford the tuition and bureaucracy of film schools but still have a dream.

Spike Lee in Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

How did Do the Right Thing come about?

It started because of the whole Howard Beach incident. I wanted to do something to address that and racism. It’s been reported several places that this film is the retelling of Howard Beach. This is a completely fictional thing. We took four things from it: the baseball bat, a black man gets killed, the pizzeria, and the conflict between blacks and Italian-Americans.

How did the ideas develop for the film, and how were they influenced by logistics? It’s hot material.

I wanted it to be one 24-hour period, the hottest day of the summer. I wanted the film to take place on one block in Bedford-Stuyvesant. So that’s all the stuff I needed to work with, to start with. From there I could just go ahead and do what I had to do.

The script doesn’t come to life till you shoot it. The finished film’s always going to be different. I’m always true to what I’m saying, but the most important thing is to do what’s right. If I write something, and it comes out in rehearsals that something else is better, we change it.

Every time I do a film , people ask me, “Did you have full artistic control?” I mean, She’s Gotta Have It, School Daze, and Do the Right Thing—we made the films we wanted to make.

How did the character of Smiley, the Dostoyevskian “village idiot,” develop?

He’s not in the script at all. It came about because Roger Smith, the actor, kept hounding me. So we went for something that wouldn’t seem like it was just an afterthought.

Roger Smith, who plays Smiley, doesn’t have cerebral palsy in real life?

No, that was an act. We just wanted him to be a different character.

Who is Mookie, the character you play? His relationship with Tina, the mother of his child, is unresolved. We don’t really know what his hopes and his dreams are, except wanting to get paid.

That’s all it is. Just live to the next day: He can’t see beyond the next day. Mookie is an irresponsible young black youth. He gave Tina a baby. He changes, but up to that point he doesn’t really care about his son or her.

The end of the film is very powerful, and yet, somewhat ambiguous. How do you reconcile the two quotes, one from Dr. King and the other from Malcolm X?

Well , I don’t think it’s ambiguous. I think you really have to concentrate on what the final coda of the film is: the Malcolm X quote, not the Martin Luther King quote.

Malcolm X said, “I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence… I call it intelligence.” Is the riot then, doing the right thing?

In that specific case it is, because Mookie and the people around him just get tired of blacks being killed by cops, just murdered by cops. And when the cops are brought to trial, they know nothing’s going to happen. There’s complete frustration and hopelessness.

They’ve seen it so many times: Howard Beach, Michael Stewart, Tawana Brawley, Eleanor Bumpurs. Nothing happens. The eight cops that murdered Michael Stewart—that’s where we got that Radio Raheem stuff. That is the Michael Stewart chokehold. Except we didn’t have his eyeballs pop out of his head like Michael Stewart’s did—[the police and medical examiner] greased his eyeballs and tried to stick them back in the sockets. There’s a complete loss of faith in the judicial system. And so when you’re frustrated and there’s no other outlet, it’ll make you want to hurl the garbage can through a window.

If you read about an incident like the one in Central Park in the Amsterdam News and then compare it with The New York Times coverage there are two different perspectives…

A couple days later a black woman was found raped and murdered in a park. No mention of it—you didn’t see nothing—no head lines in the Post, Newsday, Time, New York Times, or New York Daily News. That’s a devaluation of a black life. It’s like black life doesn’t mean anything, doesn’t count for anything.

As long as they see, well, it’s niggers killing niggers, they’re animals anyway, it’s no news. But if a young woman—a young white woman, on top of that, from Wall Street—is raped in Central Park, you might as well spit in the face of Jesus or something, because, you know, a great atrocity has happened.

This [black] woman was raped four or five days after the incident in Central Park. Raped and murdered! Nobody said nothing. Didn’t see no outcry. I didn’t see Donald Trump taking any fucking ads out behind that shit.

The fight in your film was between the most sympathetic white, Sal, and the two least sympathetic blacks. For instance, Buggin’ Out, the activist, couldn’t get any people on his side except Radio Raheem. John Turturro’s openly racist Pino would have been his most likely counterpart.

See, that’s what Hollywood would have had. But that’s too easy. Pino didn’t pick up that stuff out of the air. Some of it had to have been taught him by his father, Sal.

What’s really troubling to some white critics is when Mookie throws the garbage can through the window. Because Mookie’s one of those “nice black people.” I’ve heard a lot of white friends tell me, “You’re a nice black person, you’re not like the rest.” They really followed Mookie, they liked Mookie. He was a likable character. [Laughs] They feel betrayed when he throws the garbage can through the window. Can’t trust them. The Moulan yan. Telling him to get a spear. [Screams. Laughs.]

“Moulan yan” means eggplant.

Haven’t you seen any Martin Scorsese movies?

John Savage and Giancarlo Esposito in Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

Were the events leading to the riot a way to say that even the “nice” whites are willing to hide behind the colonial power structure?

Sal says, “These people love my pizza.” I mean, any time you hear someone say “youse people,” you know what that is.

Although he seemed proud that everyone grew up on his pizza…

Yeah, but look, as soon as the shit started to happen, all of a sudden he starts saying, “I’ll break your fuckin’ nigger ass.” That didn’t come out of thin air. It was there. It just had to be provoked. But it’s still there, though.

Why provoke the fight in a seemingly safe civil arena, a gathering place, rather than on the street?

Well, that’s where a fight like that would start. In the public eye. Buggin’ Out’s character is a direct reference to the couple days after the Howard Beach incident. Some black leaders got together and wanted all the black people in New York City to boycott pizza for a day. It was one of the most ridiculous things I ever heard in my life. It was stupid.

I mean, Buggin’ Out has the right idea. But what’s going to be the value of having one black photo up on Sal’s wall of fame? Is that going to do any good? But on the other hand, he also has a point, because let’s turn it around and say, “Look, Sal, you make all your money off black people, why don’t you have enough sensitivity to have at least one photo up on the wall?” So that’s the way the film is to me. Everybody has a point.

And are you advocating for the riot at the end?

I’m not advocating anything. These are just characters, and this is how they act. This is how they acted. And if we turn that around again, I think Sal has a point, too: When you black people get together and have your own businesses, you can do what you want to do.

I don’t think that blacks are going to see this film and just go out in the streets and start rioting. I mean, black people don’t need this movie to riot. They’ve been doing it already. Just look at what happened in Miami the week before the Super Bowl, when those cops killed people. Now some people be killed in New York City in summer by the cops, and this movie’s not going to help. But it’s going to be tense here in New York anyway, with this whole mayoral election coming up. And it’s going to be hot, you know. That was the whole premise of the film, that in 95 degrees people lose it anyway.

Do you think that the “wilding” incident in Central Park will affect the film’s reception?

I never even heard of the term “wilding” before this movie came out. It’s like they got this thing, they made it up, you know. I’m very sorry that the young woman got raped. It’s a terrible act no matter who it happens to. But I think the whole thing was blown way out of proportion. The media just whipped white New York into a frenzy, and Donald Trump wasn’t helping, taking out them ads: bring back the death penalty—they’re code words. Anytime you hear Ed Koch talk about “savages” and “animals” you know he’s talking about young black males. It was the whole Bernhard Goetz thing right away. And definitely this is being tied into the mayoral race. It’ll come up again: a vote for [black candidate] David Dinkins is a vote for wilding. I can see a campaign like that for sure.

White people fear that you are advocating violence.

Look, all they have to do is read the last quote of the movie. I’m not advocating violence. Self-defense is not violence. We call it intelligence. People are full of shit. Israel could go out and bomb anybody, nobody says nothing. But when black people go out and protect themselves, then we’re militants, or we’re advocating violence.

It seems you almost glossed over the death of Radio Raheem. When Mookie goes to see Sal at the end, he just says, “Radio Raheem is dead.”

Yeah, but that’s Mookie’s character. What happened that night was tragic, but Mookie’s whole character is not going to change overnight. And the reason why he’s there that morning is because he wants to get paid. He’s been saying that the whole movie, you know, get paid, get paid.

No, I don’t think I glossed over it. What’s the last thing that Love Daddy says? “The next record goes out for Radio Raheem. We love you, brother.”

When Mookie breaks the window, it’s his decision to get off the sidelines, take a stand and really explode the situation… Is that you?

We’ve always tried to take a stand no matter what. All creative filming does. I don’t think that we’re going to change anything. This is just a more explosive, volatile subject matter.

Is Mookie symbolic of art taking a stand?

Of art? No. I leave that up to you journalists.

Spike Lee and Danny Aiello in Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

After the riot, the only people who lose out at the end of the film are the people who live in the neighborhood.

That always happens. Look at the riots in ’67, ’68. Anytime there’s a riot, the National Guard, police—whatever—they always make sure they contain that riot to the ghetto. And so the buildings they burn down will never be built back.

When there were riots in New York City, they were never on Fifth Avenue. There’s never been looting in Lord & Taylor’s or Saks. It was on 125th Street. So, in a way, we do lose out. But people don’t feel they lose out, because they feel they lost already. People have nothing to lose.

Before the riot they had the pizzeria, whatever that meant. But now, the street’s the same except it’s filled with debris and they don’t have a pizzeria anymore.

They felt better about it, though. They felt that for once in their lives, they’d taken a stand. And they felt that they had some kind of say. They felt powerful.

It’s brought up several times in the film that “it’s a free country. “ Your character brings it up at one point; Clifton, the yuppie who moves into Bed-Stuy, brings it up. It’s a very ironic statement.

Well, yeah. That was no accident.

The street in the film—that was the cleanest street I’ve ever seen in New York.

I made that choice because any time you hear people say Bed-Stuy, right away they think of the rapes, murders, drugs. There’s no need to show garbage piled up high and all that other stuff, because not every single block in Bed-Stuy is like that.

It would be a fallacy to say that lower-income people always live in burned-out buildings. These are hard-working people, and they take pride in their stuff just like everybody else. So there’s no need for the set to look like Charlotte Street in the South Bronx.

Another thing people ask: “Where are the drugs?” Drugs is such a massive subject, it just can’t be dealt with effectively as a subplot. You have to do an entire film on drugs. This film was not about that. This film was about racism.

The people in the film are very intelligent. The most ignorant person is Pino. Is there a difference between violence in the hands of the ignorant and violence in the hands of the intelligent?

Intelligent people will use violence to their advantage and ignorant people just use violence for violence’s sake.

But if you had really ignorant people fighting back the riot would have carried a different weight.

No. I think that it is good these people were intelligent. Because then it shows this is not just a case of random violence. People knew exactly what they were doing.

And if they had jobs? Mookie says several times, “Get a job.”

He gets that really from working for Sal. “Get a job”—that’s really a statement on your manhood. Because every man should be able to hold his own weight. And what’s the first thing Pino says to the guys who are heckling him, when he’s beating up Smiley? “Get a job!” Because a lot of these guys don’t have jobs. Therefore, in Pino’s eyes it means that they’re not men. “All the Moulan yans are on welfare anyway.”

Rosie Perez and Spike Lee in Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

Your screenwriting and filmmaking aren’t strictly narrative. They bear a strong resemblance to a musical score. Each character is a note that you play and then bring all together for a crescendo at the end.

We just don’t like to have narratives that show. They’re there, but we just don’t want to be out in front, because when narratives are out in front, the audience will be able to guess from watching the first ten minutes of the movie exactly where you’re going to go. We like to keep them guessing, just let there be work. I think that for the most part, not enough respect is given to audiences’ intelligence. They’re just spoon-fed everything.

When School Daze was released, it was lumped together with… Shoot to Kill and Action Jackson.

They all came out on the same day. They just think that the black audience is just one monolithic audience and has no diversity at all—which I think is very disrespectful. There’s no way Shoot to Kill is a black film. Very few black people went to see that film. Sidney Poitier was the only black person in that movie.

In your book, Do the Right Thing, you say that blacks can’t be held responsible for racism, that they’re victims. It seems that one’s self-perception as a victim reduces one’s power—as seen in the conversation between M.L., Sweet Dick Willy, and Coconut Sid about the Korean fruit stand.

No. How is that going to be “my perception” if black people were taken from Africa as slaves? I’m not imagining that. You must acknowledge that, but not use that as an excuse.

When I was becoming a filmmaker I knew it would be harder for me to be a black filmmaker—to be a filmmaker because I was black. But I realized that you just have to be two or three-four times better. The same thing as any black athlete. They got to be better than the white boy to make the team. You don’t sit there and brood about it. This is something you just know, growing up black. It’s a given. The problem starts when people say that’s a given and then use that as the excuse.

I was reading an article in Premiere about blacks in the film industry. And one person was quoted as saying Hollywood films are based on the premise that a black man or woman can’t lead you anywhere. Which is to say that whites’ moral/psychological identification can’t be with a black person.

I truly believe a lot of people—a lot of executives—believe that. There’s an age-old axiom in Hollywood that black is death at the box office. Except for very few exceptions—Eddie Murphy being one. Look at Time the week they had Mississippi Burning on the cover. Alan Parker said the realities of Hollywood today demand that this film have two white leads. And I’m not going to hang Alan Parker about that statement. I think that he’s just echoing what a whole lot of executives feel, the people who get pictures made.

No matter what you do—you can be as big as Michael Jackson—they still look at him as black first. So, you really can’t get around it. But it doesn’t bother me.