Interview: Shirley Clarke

Miss Polt, who has written for American and European film magazines, interviewed Shirley Clarke while both were attending the Venice festival last summer. This article appears for the first time in English; it was published originally in Czech translation in Film a Doba, Prague.

How did you get your start in filmmaking?

My first film was a short dance film called Dance in the Sun. When I saw the first rushes I was horrified: it was just terrible. I debated on whether to finish it or not, but I finally decided to go ahead, because if I didn’t I would never learn anything. Still, most dance films are so terrible that mine was among the best, and it won a prize. This made me an authority on dance films. I then made two more dance films and a number of other short features: seven all together before I made The Connection. One of the shorts, Skyscraper, won a prize in Venice and also in the U.S. and gave me a name, making it possible for me to go into features. The first film I really felt strongly about, though, was Scary Time, a film I made for UNICEF. It is a kind of stream-of-consciousness film juxtaposing shots of kids dressed for Halloween as skeletons, and other kids who really are skeletons. The film ends with a long, long shot of a Moroccan baby whose face is all covered with flies; all through the shot, the baby never moves to brush the flies away, as if to say, isn’t everybody covered with flies? UNICEF hated this and wanted me to cut it from the picture, but I refused. The film is hardly ever shown. It was made to be used in Western countries, to influence people to get their governments to give money to UNICEF. But so far as I know, it has never played in the U.S. and probably not in any of the Eastern countries either.

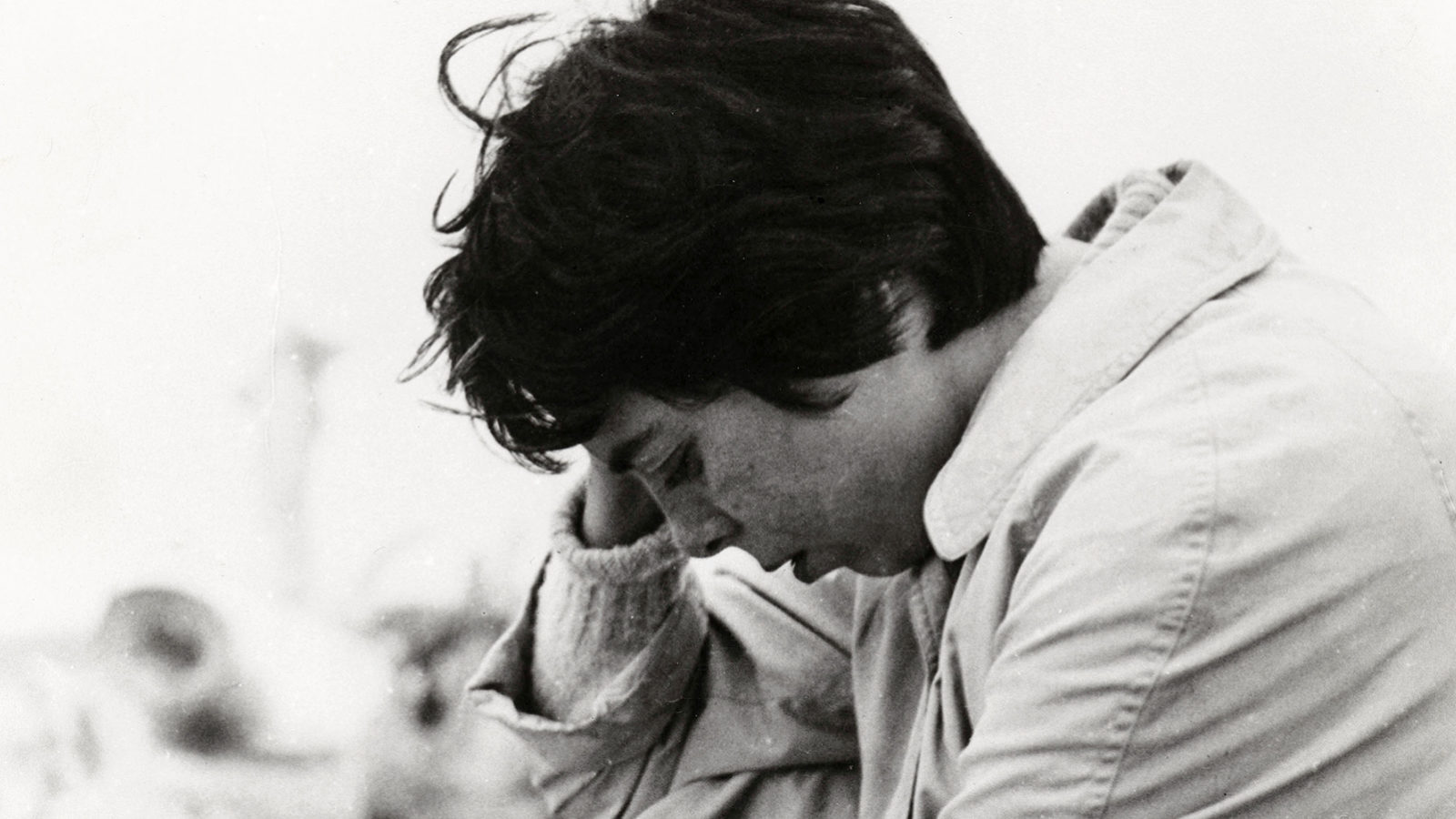

The Connection (Shirley Clarke, 1961)

How did you come to make The Connection?

It was easy. I went to see the play and decided I wanted to make a film of it. The author, Jack Gelber, sold me the rights to it. He had refused a number of other filmmakers before me.

Do you intend to go on making features or do you plan more shorts?

Economically, it’s impossible to stay with shorts. You have to find a sponsor, and then you might as well be working for Hollywood.

How do you feel about Hollywood? Do you have any intention of making a film there?

Never. Hollywood has preconceived ideas about what audiences want. The Hollywood idea is that films about Negroes or films about young boys don’t make money. I would never have got money in Hollywood to make The Cool World.

Where did you get the money to make your films?

I raised it from many people, like the people who give money to put on plays and are interested in the glamor of being an “angel.” Of course, you have to keep costs down and only plan films that can be made on a low budget. The Cool World cost $250,000, which is about a fourth of what it would have cost to make in Hollywood. But the ease with which one can get money for a film depends very much on the success of the last film.

There is much talk of a “New York School.” Do you consider yourself a part of this?

I’m not sure there is such a thing. Both in New York and on the Coast there is a renaissance of films being made by individuals. These individuals come in two varieties: the young men who are trying to get to Hollywood, and the kind who want to remain personal and keep costs down. This is the only common ground.

Mrs. Clarke, how does it feel to be a woman film director?

It’s fun. I find it an advantage being a woman, but perhaps that’s because I am used to being one. I find that I can get away with things that a man wouldn’t. At first I was worried about having problems with male crews, but then I found that those who don’t like working with a woman simply don’t join up. Pretty soon we begin functioning as people, not as members of different sexes. I do have some trouble working with actresses. I didn’t get along at all with Yolanda Rodriguez, the girl who played Luanne in The Cool World.

How did you become interested in the Negro problem?

For the past four or five years I have felt that this is America’s key problem. Without a solution to it, we will never have a free country. After all, we whites are in the minority—two thirds of the world is colored.

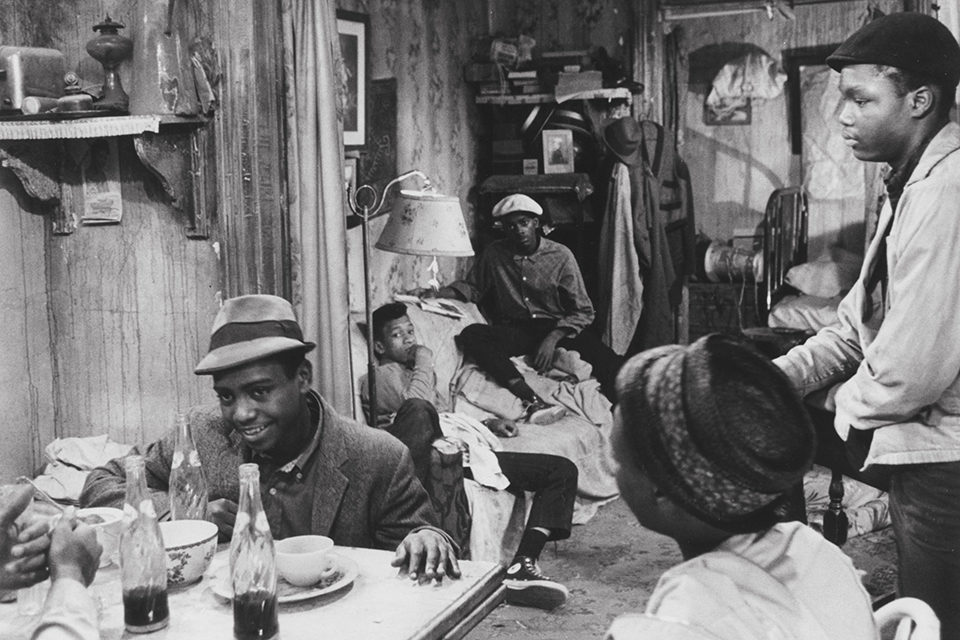

Gloria Foster and Hampton Clanton in The Cool World (Shirley Clarke, 1963)

Can you tell us something of how The Cool World was made?

The exteriors were all shot on location in Harlem. For the interiors, the New York Housing Authority gave us the use of a whole tenement building which was about to be demolished. For each set, we used a different floor of the building. We didn’t have to buy a stick of furniture—we just used what was there. Our interiors were all pre-lit, so we could move the camera freely. Throughout the film, the camera was hand-held. For sound, we used radiomicrophones, so we didn’t need a boom. The film took almost a year to make, plus four months of casting.

How did you do your casting?

Carl Lee (who plays the part of “Priest” in the film) did most of the casting. He went around to all sorts of youth organizations—settlement houses, social clubs, and so forth. Everywhere he went, the directors would bring out their star pupils. But these kids were completely unable to act. Then Carl would see some kid slinking around the school yard and would ask for him. “You don ‘t want him!” the director would say. But we took these kids to a big loft that we had, and we began improvising from the story. This got them acting, and also made the whole thing possible, because, although they are very bright, many of these kids can’t read. We used this technique throughout the film—a mixture of memorizing lines and improvising. You can’t get quiet, tender moments by improvising, so those we had to write out. But many of the others we improvised, using a straight Stanislavsky technique either before or during the shooting. We never did a scene without checking with the kids first to see if the action seemed believable to them.

How do you like working with non-professional actors?

Well, I worked with a combination of professionals and non-professionals which is confusing. You have to try to make the non-professionals be what they are, and at the same time you have to break the professionals of their bad habits. The kids had no bad acting habits or preconceptions. They were just wonderful to work with—working 18 hours a day, seven days a week, for 12 weeks without a complaint. And shooting a film can sometimes become pretty dull for the actors.

What has become of these kids since The Cool World?

These were all kids who had police records. The life they played in the film was pretty much the life they had lived. Now they’ve changed. Hampton Clanton, who plays the lead, is finishing his last year of high school and goes to a neighborhood playhouse. The boy who plays the leader of the enemy gang is working as a messenger for a playhouse. Some of the boys are acting in an off-Broadway play that our set-builder has written. I don’t know what Yolanda Rodriguez is doing—she didn’t want to be an actress at all. We had to beg her to come all the time. She was working after school for a bra manufacturer, which interested her much more than the film.

How do you explain the change in the lives of these boys?

Their main problem is a lack of self-identity, of dignity. The film gave them a sense of pride: the idea that they are important enough to make a film about what we’re curious about is how these kinds of kids will react when they see the film. We would like them to come out a little straighter and prouder than when they went in.

The Cool World (Shirley Clarke, 1963)

What are your plans for future productions?

Right now I feel I am still working on The Cool World. The film was barely finished when we brought it to Venice, and it still needs some cutting. After that, I want to take a couple of months to plan for the next two productions. I would like to keep the same producer and the same technical people. Eventually, I would like to form a co-op with other directors and produce for each other. We have various enough backgrounds in film that we have an overall knowledge of how to make a film. That wary, too, we could covet each other’s losses. So, if one director’s film loses money, another will gain, and the co-op will still break even. I’m not the only person who wants to do this sort of films I’m doing, or the only person with talent. But talent isn’t enough for a modern artist. He has to be a salesman too. And he has to be willing to plunge in, as I did with that awful dance film. Other people are too cautious. As for me, I don’t care. If the film doesn’t succeed, it’s only money, or a few years of your life.

Do you expect to have any trouble with censorship, as you did with The Connection?

We won the court case in New York with The Connection so we shouldn’t have any trouble. Some cities, for example Chicago, still won’t play The Connection. Burt most cities that have a censorship board will follow New York’s lead. Of course, it did take a year to get that case through the court.

If it’s not being too personal, how did you eat during that year, or at other slack times?

Most filmmakers have to accept commissions or films, or do other little jobs. I’m lucky—I have a husband who has a regular job.