Interview: Jeanne Moreau

Jeanne Moreau wasn’t expecting me. The elegant grand-bourgeois apartment was still as Armelle Oberlin, Moreau’s faithful assistant, peered out from behind the heavy wooden entry door. “What interview?” she queried, visibly searching her mind for a reminder, a sign. I possessed, after all, the code that unlocked the forbidding downstairs porte cochère.

Oberlin led me into the library and disappeared into the apartment’s silent folds. As I waited, the gray Parisian light impetuously revealed clues to the maitresse de maison’s personality: books by Nabokov, Heilman, Highsmith, and Wolfe; Fine 120 and Marlboro light cigarettes; texts on numerology and psychology; sheer, sexy, black stockings carelessly tossed over the back of a chair. I was lost in reverie, in some black and white Eric Rohmer moral tale about middle class infidelity, when Moreau’s unmistakable voice called my name and jolted me back to work.

She was wrapped in a pink chenille robe, wild white-blonde hair, and cigarette smoke. At noon, Moreau had just gotten out of bed. I had seen her the night before playing the title role of La Celestine at the Odeon Théâtre. In a dazzling performance as Fernando de Rojas’ manipulating matchmaker-sorceress, Moreau forever climbed up and down the myriad steps of the impressive deconstructivist set of a Spanish village; I knew, this morning, she had to be exhausted. Ever the professional, Moreau rescheduled for later that afternoon.

We sat in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, in the now familiar library, and spoke a lively combination of French and English. The daughter of a French barman and a Lancashire chorus girl who danced at the Casino de Paris, Moreau is in an abundant period of her life and appears joyfully bien dans sa peau. Besides two critically acclaimed theater runs, film work has kept her traveling nonstop for months. She was on her way back to Russia, where she is shooting Anna Karamazov. Afterwards she will travel to Australia to play a blind woman in Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World. Moreau may also direct the French stage version of Steel Magnolias, wants to hire Jim Harrison to write a film for her, and hopes eventually to finish directing her series of portraits on the first ladies of American cinema.

A month later, I ran into Moreau in Florida at the Sarasota French Film Festival, where she was being honored with a special tribute. Since our Paris interview, her mother had died; when we hugged and I offered my condolences, there were tears in her eyes. In her 60s, Moreau still tried to please her mother. In Paris she beamed over a rave review of La Celestine from the London Times; it meant even more to her than the French critiques, since her mother, who lived in England, had seen this one in the paper. Moreau was reluctant to stay for the Sarasota screening of Jules and Jim—she was afraid she would cry, afraid she would be flooded with memories of her mother who had been with her on the set during the filming.

Ever the professional, Moreau remained in the theater after the tribute. In the darkness, she took her seat. In the darkness, her eyes, dry, remained glued to the screen.

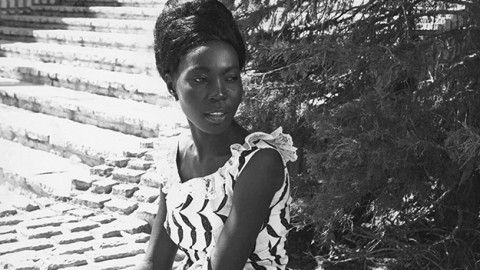

Jules and Jim

You’ve come full circle: summer 1989 you were performing La Celestine with the Comédie Française at the Avignon Festival where you actually made your stage debut many years ago.

It seems symbolic. But it’s only a symbol on a calendar. It doesn’t really affect me deeply.

I started acting in 1947, so I’ve come back to the Comédie Française after 42 years with all this energy, this vitality—I’m obviously not aging in a conventional way. On the other hand, death, the end of a life, affects me.

Life is about chance meetings. Some people live sorry lives where they stay in the same spot and frequent the same people. My destiny is such that, as an actress, many people have the desire to meet me and have sought me out. I’ve just worked on a Soviet film where I’m the only French person. My life is like that. Or, I met Klaus Michael Gruber, the director of La Zerline, and he introduced me to the play, which we performed throughout Europe and which we’ll next take to Tokyo and then to Broadway in 1991. It’s all about chance.

You obviously identify with Jim when he says, in Jules and Jim, “Je suis un curieux.”

Absolutely. My curiosity is stimulated by everything in life. The only thing I’m not curious about is politics, because it’s all about egos and power. I find it boring and dangerous at the same time. Of course, I know what’s going on in the world and how the world transforms itself. I know about East Germany, Vietnam, the Khmer Rouge, China. It doesn’t mean that I’m not curious about what’s going to happen, but unfortunately the worst always happens. So I try to be constructive.

I have enormous curiosity. As soon as something crazy comes my way—like a Soviet director who says, “I can’t pay you. You have to pay your plane ticket; the only thing I’m sure about is that you’ll have food and a good bed”—I go.

Or like Wim Wenders, whom I’ve known for years, even before he made his first feature. When he asked me to be in his next film—even though I hadn’t read the script, I said yes. Fun, I want to have fun in life.

Tell me about this Soviet film.

The film is called Anna Karamazov from one of Nabokov’s novels, Pnin, about a Russian man who is a teacher in the U.S. The title comes from a student who says she wants to learn Russian in order to read “Anna Karamazov,” meaning Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov. The director, Roustam Khamdamov, is a young man who has been hiding and, because of the new politics and Gorbachev, has been allowed to make his film. It’s a big-budget film and they’d like it to represent the Soviet Union in Cannes in 1990. They asked me to do the main part even though I’m French because Roustam, in hiding, had been looking at pictures of me in magazines and dreaming about me doing the film. We filmed for five weeks in Leningrad and we still have eight weeks shooting in Moscow. I have a feeling there’s something extraordinary here.

The Russian crew had never seen me onscreen, so when I arrived I was like a beginner to them. Everyone— the grips, the electricians—went to the rushes asking, “How is Jana?” And the next day on the set they were all tapping me on the back saying, “You’re a big star, you’re fantastic!” It was as though I had passed an examination at 61 years old.

Viva Maria!

Where does your zest for living come from?

Maybe it’s because I’m very grateful. Every day I think about how lucky I am. Before going out on stage, when I hear the murmur of the audience, I’m full of energy thinking that so many people gather each night to see me perform. I’ve been doing Zerline for three years—I did that play 300 times—and wherever we went, the house was full. You have to be grateful for things like that.

I never thought of my life in terms of career. Very early on when I became successful, I instinctively felt the danger and I didn’t want to be part of the star system. That frightened me, so I moved away from it and said no to lots of things. I lived very freely,

I traveled, I fell in love, I did nothing, I read. And many people said that I was destroying my career. But I didn’t want a career. And now that’s my strength.

I do not belong to any category. That’s total freedom. And because of that, I don’t worry. And by not worrying I’ve kept a very childlike attitude toward being an actress. I enjoy it immensely.

You’re one of the stars most associated with the French New Wave. What was the New Wave for you? Did you feel, at the time, that you were in the process of writing the history of French cinema?

The first star of the New Wave was Brigitte Bardot in Vadim’s And God Created Woman, which was made just before Truffaut, Chabrol, and Godard made their films. It was a premonitory sign. Brigitte lived out her destiny totally differently. I had already been making films for ten years when I started working with Louis Malle and Truffaut.

When I made Jules and Jim, I had the feeling, instinctively, that it was something very, very special. During the first days of shooting you know how things are going to be. Strangely, I have the same feeling about the film I’m making now in Russia. But when I made Jules and Jim, I was at that age where one lives very egocentrically; I saw it as the chance of a lifetime. A chance to escape the “star” style. I didn’t even really think “star”; I was thinking of the stereotypical cinematic style—lots of makeup and hair done just right, always being followed around by the hairdresser, makeup woman, costume fitter. All of a sudden we were filming in the street, with very little makeup, costumes you found yourself. No one was telling me anymore, “You have circles under your eyes, your face is lopsided.” Makeup was done in ten minutes, your hair was washed, dried, and you were out the door. Suddenly the natural look was in. When they did a closeup it no longer took half an hour under the lights—“Lower your face like that, no, like that”—and then if you lifted your head they’d scream, “The lights!” Suddenly it was life. And I felt that if I was going to thrive and have fun working in front of the camera, it would be like that.

No less Malle than Truffaut or Godard or Chabrol or Rivette thought they were writing the history of the cinema. We weren’t thinking in those terms; each one saw his own personal destiny. But I felt that it was, yes, very important.

How would you characterize the different decades in French cinema with regard to how women were viewed?

The Fifties dealt with the conventional relationship of the couple. Most films are made by men and the woman, who is born in the cinema, is born out of a masculine vision. It was the goddess, the prostitute, the mother.

The New Wave in the Sixties had a more exact and fresher vision. In the Fifties they portrayed relations between men and women as they would have liked them to be; in the Sixties they tried to understand what was really going on. The New Wave extended beyond films; it was a new attitude towards life.

Then, in the Seventies and Eighties, the woman’s place lost its power. With the moral evolution, with women’s liberation, and women’s demands for autonomy, the idea of the couple and obedience to the master and the husband was no longer valid.

Women wanted the same status as men, and of course it provoked a reaction amongst men, which, because of fear, translated into aggressivity. Look at Brian De Palma. In his films the women are always beaten and killed. I know De Palma and I think he’s a very good director, but so many other directors do the same thing. My ex-husband, William Friedkin, doesn’t make films about women. He erased them completely out of his world. Suddenly, men’s imaginations couldn’t function in the same way.

It’s not only because of feminine emancipation, it’s also about moral liberty and sexual freedom. As soon as we can consume what we want, when we want it—whether it’s a piece of cake, a woman’s body, or an apple—it loses its magic. The sacred side of things has disappeared. Sex has become like a good steak, a drink, like pissing, like shitting. And it hasn’t made people happier.

It’s no longer sacred. I’m not talking in religious terms, but about all those things that carried a taboo and that we had to experiment with in secret. Every human being had a relationship with something taboo that he owned in secret, but as soon as everything was out in the open, the taboos ceased to exist. There were no private treasures hidden anywhere. We thought we had won—everything was allowed and we felt like we owned the world. But the secret, precious little thing that we owned was lost.

We see this in the films, in the characters who make us dream. But this, too, can change. Man never owns anything for a very long time. Starting with his life. You lose it. You lose everything, good and bad. If you have something that makes you happy, you’ll lose it. If something happens to you that’s painful, it won’t last either.

The Bride Wore Black

I heard that on the set François Truffaut would give you written direction, that he rarely spoke directly to you.

The communication was very intimate but we didn’t use words.

How did he, as a director, influence you?

He didn’t. Real directors don’t try to transform you, they allow you to become a character. It was intimate work that went on and on. If there was any influence, it was a shared experience. Through me François learned about women, and through him I learned about cinema. As in any profound relationship, there were the ups and downs.

François was not pleased with my decision to direct films—to him it was shocking. I was supposed to be a star; to be that untouchable woman, not someone directing a crew, organizing things, and making a film. It was as though I were losing my femininity. François had a very classical point of view. He didn’t want me to direct, because he didn’t want me in the battlefield. He once said to me, “You know, people say jealousy is very violent between actors and actresses, but frankly the most violent competition is between directors.”

I have been asked to make a film about François, which I’d like to do more than anything else. I’d like to give him that proof of love. It was to be three one-hour films for television —a portrait. I could start working on it next summer, but it probably won’t get made until 1991.

Wasn’t Orson Welles the only person who actually encouraged you to direct?

Yes. He was staying at the Hotel Meurice preparing The Trial. We had had dinner, we drank a lot of sherry and spoke and laughed. Then, looking out the window, he said, “Look at the moon.” I went to another window and saw this huge moon and I said, “Oh, the moon.” Then we looked at each other and realized we were looking in two different directions. I asked, “Where’s your moon?” and he showed me, and we realized there were two moons. Only we were actually looking at the two huge clocks, lit from the inside, on the Gare d’Orsay. And that’s how he found his location for The Trial.

That was the night I told him I wanted to be a director. His answer was, “Of course, but it’s got to be a real, powerful need. And once it’s a real need, you have the freedom.” He knew the respect I had for the cinema. But he was the only one who reacted positively.

Whatever happened to The Deep, the last film you made with Welles?

We don’t know where the copy is. We know it exists. I’m sure it’s in a lab somewhere, and I’m sure the woman he left behind [Oja Kodar] knows where it is. The decision is in her hands. I’d like her to do something about it.

Did you write to Antonioni after you saw L’Avventura and ask to work with him?

No. The director with whom I had a correspondence was Bergman. Antonioni saw me on stage in 1950. He was a beginner at that time and he asked me to do a film with him. But because I was under contract with the Comédie Française, they wouldn’t let me leave for three months to do it. That film was I Vinti. He always kept the idea of doing a film with me in his mind; that’s how La Notte came about. But I had signed a contract with his producer before he made L’Avventura.

The Chimes at Midnight

Tell me about your relationship with William Friedkin.

We were married and had a marvelous time together and a very painful time. We weren’t together long. I think he’s a great film director and I love him still. As soon as a man and a woman are involved in a very passionate relationship, it gets in the way of friendship, and collaboration in terms of work.

I read somewhere that Friedkin said actors can spoil a well-planned shot like ants at a picnic.

Yeah. I was very shocked when he said that. I even said to him, “God, you don’t like actors!” But he’s right in a way. Sometimes actors are a pain in the neck. He used to call me the Great Priestess of Cinema. Sometimes he said it with admiration and other times sarcastically.

We planned to make films together. I haven’t seen him for quite a long time. I was married to [Friedkin] just before I made L’Adolescente. He asked me for a divorce the week I started shooting. It’s interesting—he picked a good moment. When you hurt, you want to hurt.

Do you think you’ll ever get married again?

One never knows. I could live with somebody but I couldn’t submit to them. Why should I? And why should another person submit to me?

I don’t believe in romantic love anymore. Romantic love so often ends with hatred. It has nothing to do with love. It’s just passion; it’s a relationship based on an illusion. Often the lovers don’t want to see the other person as he really is—they want the other person in their image. I’ve been through it. Knowledge is useful. I may have another great love in my life, but not that sort.

At the end of Vadim’s Les Liaisons dangereuses someone whispers that the countess now wears her soul on her face. Do you think that happens as we get older?

Yes, absolutely, it’s exactly that. There are all kinds of beauty. There’s the devil’s beauty, which is a youthful beauty, and afterwards there’s the beauty we find in older people which has to do with other things.

It’s extraordinary that Les Liaisons dangereuses has been re-released. I’m still proud of it. Sometimes we do things and feel, “Okay, I did that, it’s over, now let’s forget it.” But mostly the experience that I’ve had all my life about doing things of a certain quality, with people for whom I had a lot of esteem, has paid off enormously.

What’s your greatest success in life?

My ability to live without any protection. To trust in human beings, to be enthusiastic, and to have more and more pleasure as life goes on. It’s God’s gift really.