Prizzi’s Honor

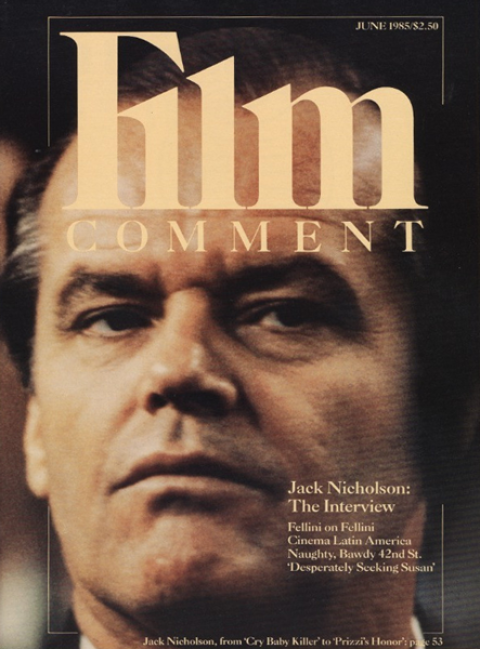

As Charley Partanna, dim-witted son of a Mafia consigliere to the powerful Prizzi family, Jack Nicholson presides over Prizzi’s Honor, his 39th film. With sincerity fairly oozing from every pore and calculation flashing from every eyeball, the whole cunning Mafioso lot manages to make the dark side of their way of life seem an unfortunate by-product of ordinary frailties. Though monstrous, they have charm.

Directed by John Huston who has kept company with such types before, most notably in Beat the Devil and The Maltese Falcon, the film features the fast-rising Kathleen Turner, Anjelica Huston, Robert Loggia, John Randolph, Lee Richardson and William Hickey as the don. However, Prizzi’s operatic tone (cinematography by Andrej Barkowiak; music by Puccini, arrangement by Alex North), its unusual mix of Runyonesque satire, and its Brechtian tragedy give it a special place in the Huston oeuvre, and suggest the presence of another, equally powerful, sensibility.

This belongs to novelist Richard Condon who, along with documentarist Janet Roach, adapted his book for the director. Condon’s co-mingling of the sacred and profane has made him one of the most popular contemporary fiction writers with something to say, not just sell. The Manchurian Candidate, based upon his second novel and released in 1962, is a classic.

Prizzi’s Honor is sufficiently iconoclastic and anti-romantic to have given cold feet to several studio executives and probably could not have been made without Nicholson, who singularly—and effortlessly—dominates the movie. With vulnerability made palpable, he makes the sotto capo inescapably sympathetic. It is not the first time Nicholson has made the preposterous dilemma of a character absolutely real. His extraordinary ability to shade his characters manifested itself in Easy Rider, the 1969 eclat which hurled him to stardom.

Easy Rider

As the alcoholic ACLU lawyer who wigs out on the subject of UFO’s, Nicholson swiped the movie. Half-way through Dennis Hopper’s and Peter Fonda’s tour through counter-culture exotica, “they come upon a very real character and everything that has come before suddenly looks flat and foolish,” wrote New York Times’ critic Vincent Canby. “The movie felt empty after his death” commented Esquire’s Jacob Brackman—and so on, and so on. Official Hollywood, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—which had not noticed Nicholson in any of his 20 earlier, low-budget Roger Corman quickies-nominated him for an Oscar. But the critics knew a tiger by his tone: Five Easy Pieces followed in 1970, and once again playing the black sheep of a distinguished family, he was called “exhilarating…a charming wastral” and “astonishingly natural.” Another Oscar nomination was inevitable.

In one of many interviews following Easy Rider’s phenomenal success, Dennis Hopper described the Nicholson character as symbolizing “trapped America, killing itself.” That description may embrace the emergent Nicholson screen persona. Time after time, the actor has evoked empathy and identification with characters whose actions and attitudes are repellent or obstreperous. In Carnal Knowledge he humiliated women; in The Shining he tried to kill his wife and son; in The Postman Always Rings Twice he made murder for love thinkable and then did it. Even when he plays sympathetic characters, as in The Last Detail, Chinatown, Reds or Terms of Endearment, Nicholson is Peck’s Bad Boy who gets away with a bushel.

Many of Jack Nicholson’s films have pushed at the outer edges of what mainstream society can tolerate. This, too, is part of his mystique. Critic Pauline Kael commented upon his “satirical approach to macho” which helps him escape our wrath. True, but some saw obscenity, not satire, in Carnal Knowledge, a film so controversial it was argued all the way to the Supreme Court.

Any person as successful and independent as Nicholson can be endlessly analyzed. Nicholson’s brilliance is his obvious, intelligent gift for both embodying and commenting upon his character in one seamless evocation. He forgives them their trespasses even as he renders them utterly transparent. It is no accident that Nicholson has always played Americans, and then usually an archetype who nearly everyone recognizes—comfortably or uncomfortably—as someone close to home. We intuitively sense something of the man himself in those squirming fictional men. “Everyone is caged but it shouldn’t be that way,” he once said. “I’ve never let anyone think they own me.”

The King of Marvin Gardens

Nicholson has never much cared what he looked like onscreen nor has he, like most stars, calculated an icon’s image for himself. He slicked his hair back and wore spectacles for The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), walked through half of Chinatown (1974) with a band-aid on his nose, turned grotesque in The Shining and scruffy in Goin’ South (1978)—the only one (of two; Drive, He Said preceded) he directed and starred in. There’s a hint of a dare to his fans in Nicholson to reject him, yet the opposite is true: He is a surgeon cutting to the bone of human sturdiness. Nowhere is this clearer than in his poignant portrayal of the seedy, out of shape astronaut in Terms of Endearment, for which he won all three major critic organizations’ awards and the Oscar—for a supporting role.

Born April 22, 1937 in Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital and raised in Neptune, New Jersey, Nicholson has become the risk-taker of his time. “He’s a very great actor,” commented John Foreman, producer of Prizzi’s Honor, in which Nicholson both looks and talks funny. “The bravest, I would say. He has gonefrom being admired to liked, to appreciated and celebrated, to beloved. He is now beloved. He is prepared to do whatever the part requires, and anything he does becomes in itself interesting.”

Tell me about your beginnings.

I got out of high school a year early, and though I could’ve worked my way through college, I decided I didn’t want to do that. I came to California where my only other relatives were; and since I wanted to see movie stars, I got a job at MGM, as an office boy in the cartoon program. For a couple of years I saw movie stars, and then AI Triscone and Bill Hanna nudged me into their talent program. From there I went to the Players Ring Theatre, one of the few little theaters in L.A. at the time. I went to one acting class taught by Joe Flynn before Judson Taylor took me to Jeff Corey’s class.

Up until then I hadn’t cared about much but sports and girls and looking at movies—stuff you do when you’re 17 or 18. But Jeff Corey’s method of working opened me up to a whole area of study. Acting is life study and Corey’s classes got me into looking at life as—I’m still hesitant to say—an artist. They opened up people, literature. I met Robert Towne, [Carole] Eastman, [John] Shaner, and loads of people I still work with. From that point on, I have mainly been interested in acting. I think it’s a great job, a fine way to live your life.

And all this while you were in the cartoon department. Can you draw?

I was invited to join the MGM cartoon department. But if I’d started work in animation I’d have had to take a cut in salary, so I didn’t. But yes, I can draw a little.

What was your first professional engagement?

Tea and Sympathy at the Players Ring. I made $14 a week. During the run I got my first agent, as well as some work on Matinee Theatre, a live TV daytime drama. Ralph Acton helped me a lot.

Of course I tried to keep my day job during this period but they closed the MGM cartoon department on me. Along with George Bannon, I was its last employee; I remember wrapping up all the drawings for storage. During the interim between jobs, I got a part in a play downtown. At the time, the only professional theaters in L.A. were road companies, but there were a lot of little theaters where you were paid about $20 a week. However, in this theater there were too many seats and it couldn’t come under a little-theater contract, so I was paid $75 a week.

While I was doing this, I got the lead in my first movie, Cry Baby Killer. Jeff recommended me. I read for it just like every other actor in town. I screamed and yelled—I know I gave the loudest reading, if not the best. And when I got the part I thought: “This is it! I’m made for this profession.” Then I didn’t work for a year.

Cry Baby Killer

Still, it seems that you didn’t have too difficult a time getting started.

But what I’m talking about covers a three-year period. For the next few years I got a couple or three jobs a year, mostly with Roger Corman, and one or two TV shows. My problem in those days was that I didn’t get many interviews. I always got a very good percentage of the jobs I went up for, but the opportunities were few and far between.

It’s been said that you gave yourself ten years to become a star. Is that true?

No. Corey taught that good actors were meant to absorb life, and that’s what I was trying to do. This was the era of the Beat Generation and West Coast jazz and staying up all night on Venice Beach. That was as important as getting jobs, or so it seemed at the time. I don’t reckon it has changed today—but I don’t know, because I don’t go to classes much.

At the beginning, you’re very idealistically inclined toward the art of the thing. Or you don’t stick because there’s no money in it. And I’ve always understood money; it’s not a big mystical thing to me. I say this by way of underlining that it was then and is still the art of acting that is the wellspring for me.

In that theoretical period of my life I began to think that the finest modern writer was the screen actor. This was in the spirit of the Fifties where a very antiliterary literature was emerging—Kenneth Patchen and others. I kind of believed what Nietzsche said, that nothing not written in your blood is worth reading; it’s just more pollution of the airwaves. If you’re going to write, write one poem all your life, let nobody read it, and then burn it. This is very young thinking, I confess, but it is the seminal part of my life.

This was the collage period in painting, the influence of Duchamp and others. The idea of not building monuments was very strong among idealistic people. I knew film deteriorated. Through all these permutations and youthful poetry, I came to believe that the film actor was the great “literateur” of his time. I think I know what I meant…

The quality of acting in L.A. theater then was very high because of the tremendous number of actors who were flying back and forth between the East Coast and Hollywood. You could see anybody—anybody who wasn’t a star—in theaters with 80 seats. But it always bothered me when people came off stage and were told how great they were. They weren’t, really, in my opinion. It was then I started thinking that, contrary to conventional wisdom, film was the artful medium for the actor, not the stage.

The stage has a certain discipline. But the ultimate standard is more exacting in film, because you have to see yourself and you are your own toughest critic. I did not want to be coming off the stage at the mercy of what somebody else told me I did.

Did you develop any concise image of yourself as an actor? Leading man? Young character actor? And how did your awareness of yourself as a potential commercial commodity square with your anti-structure bias?

I never thought in terms of typing myself, because I wasn’t that successful. After an actor has done a few pieces of work, his naïveté is the part of the craft he has to nurture most. You don’t want to know it all as an actor because you’ll be flat. As a means of supporting that experiential element in film, once I begin to work on a particular movie I consider myself to be the tool of the director.

At about that same time, I had started writing—first with Don Devlin and then with Monte Hellman. I thought of myself as part of the general filmmaking effort. And as my scope broadened, I began to think about directing. I wanted to be the guy who got to say whether the dress is red or blue. I’d still like to make those ultimate decisions. It’s like action painting. It’s not a question of right or wrong about red or blue, but that only one guy gets to say it—and if you don’t get to, you’re doing some thing else. The craft of acting interfaces with this idea.

As an actor, I want to give in to the collaboration with the director because I don’t want my work to be all the same. The more this can be done with comfort, the more variety my work has had. I think this is inherent to the actors’ craft. It is a chosen theoretical point of departure.

That’s a very European attitude.

That’s why I’ve worked with more European directors than the average actor has. They somehow understand that this is where I am coming from. And I’m not doing it to get employment. I’m doing it because I just know that sameness, repetition, and conceptualizing are the acting craft’s adversaries, and it seems more intelligent to start off within a framework where those things are, to some degree, taken out of your hands. That doesn’t mean I don’t exercise my own taste, criteria, and forms of self-censorship; but those elements have to do with who I choose to work with, on what and how it relates to the moment I start and finish. All those factors come into play, but they come into play before the action of acting.

Once you’ve started a film you don’t become a wet noodle. You must have that conflictual interface because you don’t know, and they don’t know. It’s through conflict that you come out with something that might be different, better than either of you thought to begin with.

There is one thing I know about creative conflict: once my argument is exhausted, I am not going to be unhappy whether it moves in my direction or away. That’s what the structure does for you. In the real world there’s an after-effect of disappointment if you lose an argument. But if, to begin with, you’re set up not to have this particular autonomy, then you’re not disappointed. I have never felt brutalized as an actor. Many actors do, some times, but I’ve never had that experience. If I’m not happy with the balance, I just won’t work with that person again.

You obviously saw Easy Rider before knowing the critical and public response. Did you have any clue it would become such a bombshell?

Yes, a clue. Bob [Rafelson] and I were involved in writing Head when Dennis [Hopper] and Peter [Fonda] brought in a twelve-page treatment. I felt it would be a successful movie right then. Because of my background with Roger Corman, I knew that my last motorcycle movie had done $6 to $8 million from a budget of less than half-a-million. I thought the moment for the biker film had come, especially if the genre was moved one step away from exploitation toward some kind of literary quality. After all, I was writing a script [Head] based on the theories of Marshall McLuhan, so I understood what the release of hybrid communications energy might mean. This was one of a dozen theoretical discussions I’d have every day because this was a very vital time for me and my contemporaries.

Drive, He Said

Did you think it would make you a star?

When I saw Easy Rider I thought it was very good, and I asked Dennis and Bert [Schneider] if I could clean up my own performance editorially, which they gracefully allowed me to do. I thought it was some of my best work by far, but it wasn’t until the screening at the Cannes Film Festival that I had an inkling of its powerful super-structural effect upon the public. In fact, up to that moment I had been thinking more about directing, and I had a commitment from Bert and Bob to do one of several things I was interested in. Which I did. Immediately after Easy Rider, I directed Drive, He Said.

But at Cannes my thinking changed. I’d been there before and I understood the audience and its relative amplitudes. I believe I’m one of the few people sitting in that audience who understood what was happening. I thought, “This is it. I’m back into acting now. I’m a movie star.”

You really said that to yourself: “I’m a movie star.”

Yep. It was primarily because of the audience’s response.

How did it f eel to wake up the next morning and know definitively that your life had changed—in terms of financial security, creative and other life options?

It didn’t happen quite that way—in one big zap. Because of Bob’s and Bert’s interest in me as a director, I felt on a big upswing before I arrived in Cannes. The screening there was part of a feeling that things were going well for me. Oh, I got an enormous rush in the theater. It was what you could call an uncanny experience, a cataclysmic moment. But you must understand that Dennis was there, Peter was there. We were in the boat together, so I didn’t feel the success pointed so singularly at myself.

So I didn’t wake up saying, “Gee, my life is going to be different.” I still don’t wake up that way. I don’t leap too easily to results. I’m very suspicious and wary in my way, and still get stung by people who feel I shouldn’t even be working. I always expect something horrible next.

Would you care to speculate what about you the public responded to?

It’s hard for me to know. I wasn’t a babe in the woods. I’d watched a lot of stars, from James Dean to Brando, and I’d seen everybody alive work at MGM. I had a certain old-timer’s quality, even though I was young and new, and drew on what I believed before I made it.

You’ve got to be good at it, number one, and sustain it. There are no accidents. Any kind of sustained ability to go on working is because something is valid in the way you work. The star part is the commercial side of the business—and, frankly, no one knows anything about that. The economic side is really statistical. It’s not based on the fact they think you’re going to do something good; it’s because their economics tell them this is a very good capital venture investment.

From a Jungian concept of archetypes, why is it that certain people become icons for their culture?

I believe that part of the entire theatrical enterprise is to undermine institutions. What did I know? I went from Easy Rider, where I played a Southerner effectively enough for a lot of people to think I was a Southerner, to Five Easy Pieces, where the guy pretends to be a Southerner in the first half but in fact turns out to he from a sophisticated classical-music family.

The other part of the answer is that I am reflective of an earlier audience who didn’t find the movie conventions of their time entertaining any longer—who, frankly, found them quite repressive. These same conventions were shortly thereafter flung off by the society as a whole. And once you’re rolling, you stay right there in a surf-ride on that sociological curve. The minute your theoretical meanderings aren’t valid, your work won’t be well received.

For an actor, style comes last. You first have to implement the whole thing, but your style comes from the subconscious, which is the best part an actor brings to his work. These conscious ideas are only the springboard for what you hope will be the real meat from the unconscious. I see where characters I’ve played are influencing the culture we live in.

Henry Miller wrote an essay called “On Seeing Jack Nicholson for the First Time” about my character in Five Easy Pieces. I believe Jules Pfeiffer’s writing for Carnal Knowledge was very influential. And half the people in the world still call me Randall Patrick McMurphy.

Since Easy Rider by what criteria do you select projects?

I look for a director with a script he likes a lot, but I’m probably after the directors more than anything. Because of the way the business is structured today, I have sometimes turned down scripts that I might otherwise have accepted had I known who was directing them. Witness, for example.

You’ve taken more risks with subject matter, supporting roles, or directors than any American star of recent memory. Is the director central in your taking risk?

Yes. There are many directors in the middle range who’ve made mostly successful pictures, and then there are a few great directors who’ve had some successes and some failures. I suppose my life would be smoother if I wasn’t almost totally enamored of the latter category. My choice pattern hasn’t really changed. There were Hopper and Rafelson and, before them, Monte Hellman and Roger Corman. Of course, in that period I had no choice; these are the people who wanted me.

You’ve definitely been in the vanguard of people interested in serious films, films that made statements. If you’d been in New York in the Fifties, instead of out here, your interest in European cinema and existentialist angst wouldn’t have been so unusual. Where do you think your taste came from, and how did it develop?

I imagine that somewhere out in America right now is a guy lookin’ at movies and saying: “I can’t believe this shit. I’m in high school. I don’t have any of these fuckin’ lame-o parties and a bunch of lame-o bullshit. I got serious things to do in my life. Why are they making these movies? All right, if it’s a dog picture, but don’t pretend to be makin’ this shit about me.” That’s where I think taste starts to get formed. The desire…

The Shooting

… not to be insulted.

Right. As far as European movies are concerned, Monte Hellman educated me a lot. The only European films that were distributed out here were movies like Bitter Rice, Umberto D., Seven Samurai, Rififi at the Beverly Canon. Monte and B.J. Merhols, and a guy named Freddie Engleberg who ran the Unicorn, one of L.A.’s first coffee houses, and another guy named John Fless, whom I haven’t heard much of since, formed one of the first film clubs.

There was a period when I just wanted to make what I wanted to make and I didn’t care what lie I had to tell. The two westerns Monte and I made [The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind], for example. Roger Corman only financed them because we cheated him, in a way. We told him that one of them was a kind of western African Queen and the other a variation on Fort Apache. But, what we delivered him were two very austere New Wave westerns, and he knew it. Fortunately, the budgets were such that he knew he couldn’t lose more than he’d already paid for the scripts. You had to be a little bit of a pirate in those days.

The movies were very well received. They were good for Monte’s reputation and they took me to Europe, where I met Godard and Rivette and all those other New Wave people. I think I was 26 at the time. I went to Paris on Fred Roos’ credit card, with $400 cash. I was in five countries in seven months on that $400.

What did you do during those seven months?

I hung around Pierre Cottrell’s house. He took me to every cinema thing in Paris, every film festival around. I met just about everyone in Europe who had anything to do with movies through Cottrell—Barbet Schroeder, Nestor Almendros, Richard Roud…

What year was that?

I don’t remember. It was the year Pierrot le Fou was released [1965].

Well, the late Sixties was a great period in movies. That is when I first became involved in film myself, at Lincoln Center and the New York Film Festival. I never dreamt it would change.

Boy, did it change. It’s a pity. What seems to have happened is “they” started producing the student filmmaker. This, anyway, is what my begrudging nature tells me. The problem was that “they” were a little bit too green. At first “they” made interesting pictures which didn’t make any money so “they” abandoned ‘em for blockbuster city. Then a few years passed, and Steven Spielberg arrived like the final evolution.

Filmmaking always changes. He is the top of the mountain of that particular thing, and that’s good for me. For instance, the only script Steve and I have talked about is a very human story. I figure that anybody who’s not a puppet and who’s left standing in three or four years is going to be in a very good position.

What do you mean by “anybody that’s not a puppet”?

You know, all the those movies with little herpes monsters, and wingdings, buried treasure, cars that talk, jello from every orifice, and so forth.

Don’t you think we’re moving out of that phase?

That’s what I’m tryin’ to say. A few years from now, if you can still portray a human being, you’ll be quite a valuable commodity. I intend to be there. It’s where my hopes as a director lie.

Five Easy Pieces

You’ve worked more frequently with Bob Rafelson than any other director. What is it about your relationship that keeps you both perking?

The relationship falls into the realm of the exceptional. Bob and I tart from the same point, but there are more contradictions between us than between myself and anyone else I’ve mentioned. Since we started off writing together, we know each other very very well, and there is no other director with whom I have so many conflicts when we’re working. During any given movie both of us will say, “This is it. No more.”

But I really like working with him. The guy is very caring, committed, driven, and ultimately very very smart. He’s a singular moviemaker, and to me that’s the best thing anybody can be. I like being part of that. We seem to make interesting stuff together. Among other things, we both care a lot about whimsy.

I don’t like his having rather a rougher road than I have. There is no reason for it. It comes down to style. I’m more abrasive than he is when we’re working together; but outside that framework, he doesn’t make an adjustment. That is such a false standard to judge creative talent by. You might as well judge them by what they eat.

The man has made a certain number of movies which have been economically feasible. If you ran a question through this industry about The Postman. Always Rings Twice, most people would surmise that it wasn’t successful. That is not true. I know it made money, because I received overages, so it must’ve grossed about as much as Chinatown and much more than Carnal Knowledge. But people are anxious to disqualify it.

I am real, real close to him. And I’d be doing him a disservice if I pretended to understand [his career difficulties]. I think he’s that interesting. These things have a rhythm. Bob’s been working all this time, and we’ll probably make another movie together at some point.

I’d like to talk about you as a director. [Nicholson rises and starts to move away.] Are you leaving the room?

[Laughing] No, I’m just going to get a cigarette. Discussions of my directing always get me into trouble. I either have a fist fight or a heart attack.

Do you enjoy directing?

I love it.

Why?

Let me put it this way: Both as an actor and a viewer, what I look for in a director and a movie is vision. I wasn’t mad about Roman’s [Polanski] Pirates script, but because it’s Roman I know it’s going to be a great movie. Roman is top five; the same for Stanley [Kubrick] as well as John Huston. The imagery of a movie is where it’s at, and that is based upon the director’s vision.

Everybody’s always talking about script. In actuality, cinema is that “other thing”; and unless you’re after that, I’d just as soon be in the different medium. If it’s all going to be about script, let it be a play.

The quality of a scene is different if it’s set in a phone booth or in an ice house and the director has got to know when he wants one or the other. Scenes are different when the camera sits still or if it’s running on a train. All these things are indigenous to the form.

There’s someone I know who keeps a book of drawings made by guests to her home. She ask everyone to make a drawing with two elements of her choosing: a heart and a house. The wildest one in the book was made by Steven Spielberg, and it shows exactly why he’s a great movie director. This is what he drew: a big paper heart as if it were on a hoop, busted open, through which was coming a car pulling a trailer home be hind it. Motion…movement…explosion are all there in that one little Rorschach of a drawing. Everybody in town’s in that book. If I were the head of a studio and I looked through the book, I’d stop right there and say, ‘‘This boy here is a movie director.”

So why do I want to direct? Well, I think I have special vision. If you ask anybody who was in college during the period of Drive, He Said, they’ll tell you it was the peer-group picture of the time. But it cost me because it was very critical of youth. I did not pander to them. I didn’t say, “Oh, march directly from here to the center of power and take over the universe.” Don’t suppress your feelings but don’t blow smoke its ass, so-to-speak.

I’m very proud of my two movies, and I think they have something special. Otherwise, I have nothing to offer. I don’t want to direct a movie as good as Antonioni, or Kubrick, or Polanski, or whoever. I want it to be my own. I think I’ve got the seed of it and, what’s more, that I can make movies that are different and informed by my taste. Since that’s what I’m looking for when I’m in the other seat, I wonder why others aren’t….Well, obviously because I make ‘em a lot of money as an actor.

Have you had opportunities to direct if the movie included your starring in it?

Yes, but I don’t want to be scattered. I prefer to approach a film full-scale. Take Moon Trap as an example. It’s a western I’ve always wanted to make, and I still will, some day. When I started the screenplay—and that’s nearly ten years ago now—I said to the production company involved: “Don’t make me spend my summer writing if the only way you’ll make the movie is with me in it.”

There are two parts in the picture, and they wanted me to play the younger part, which I felt a little too old for. But more than that, I had a list of people I wanted to play that part. Jon Voight was on it, and Dennis, also John Travolta before he’d made a movie, and Tommy Lee Jones, Richard Gere, and Freddie Forrest. George C. Scott and Lee Marvin both said they’d play the older part. But the studio wouldn’t go for it so I dropped the project. But since I own the material and I’m getting close enough to play the older part, I may still get to make it.

Did you write the script yourself?

Alan Sharp came in after me and improved it.

Head

Have you been doing any other writing in recent years? The last credit I see on your filmography is for Head.

I’ve contributed to other things, such as Goin’ South and the scene on the bluff with my father in Five Easy Pieces. I love writing, but I stopped because I felt I was more effective approaching filmmaking from a different vantage point. At this moment, I suppose I can do more for a script as an actor than as a writer—in the film sense. I wrote right up to Easy Rider, at which time I became someone who could add fuel to a project as an actor. I’ve always approached film as a unit, but you have to work your own field.

Jack, will you not direct again until you can do what you want, your way?

There’s nothing I’d like more creatively than to make a film on, say, the tone of My Old Sweetheart by Susannah Moore. It’s a tremendous first novel by someone I’ve known forever. If this were the period we keep talking about—the late Sixties, early Seventies—I could scheme that movie onto the screen. That, or Lie Down in Darkness, or Henderson the Rain King.

But I can’t guarantee how much money a movie based on any of that source material would make, and you can’t mortgage your life for favors just to make one movie. I can’t go out there and say, “Look, Barry…or Sid…or Guy.” These men are friends of mine, smart, and I’ve got nothing to say against them. I believe in making all movies at their most reasonable. That I get a lot of money as an actor is because nobody else will get it if I don’t. It will not be ploughed into another movie. That money is better off with me. [Laughing]

I don’t want to make a better “alien” movie. If I did, it would probably reflect the period we’re so fond of. I’d do it Alphaville-style: Take out all the art direction and mix in a little Krapp’s Last Tape.

In three of four years I can make the kind of movies I want to make. I’ll still feel a little like a pirate. The center’s always in the middle, but the studios will be a little bit less in that center lane than they are now.

Prizzi’s Honor must find the adult audience this summer. I looked at what’s being released around the same time. There’s something about discovered pirate treasure, gnomes, reporters who keep old typewriters and pretend they’re beach bums. There is all this stuff which I call an offshoot of student humor and preoccupation. Something has got to give. People don’t go on liking the same things. Skirts go up and skirts go down.

That’s why I went with Terms of Endearment. It was the most human script I’d read in years, and I just knew it would be successful. Why? Product difference. To a studio executive who’s in a more intense flow, product difference looks like danger. But to someone like myself who is one step removed, that’s what you’re looking for. That wave is going to break, believe me. A lot of good things will get made that haven’t been done yet.

Terms of Endearment

So we shouldn’t expect to see you behind the camera in the next few years?

Let me put it this way: I’m available to direct almost anything. But, to be honest, I don’t get a lot of offers. The funny thing is when I’m asked, it’s invariably by another director. Bogdanovich offered me a project once, and Francis [Coppola] and Fred [Roos] wanted me to do On the Road. There are offers that are here one day and, because I’m not immediately enthusiastic, are gone the next. I respect those guys for even thinking about me because they don’t have to.

Do you feel the more auteur-oriented directors are generally smart enough to incorporate a star into their own vision?

Yes. The people I work with are auteurs in the sense that if they want something a certain way, they’ll get it. I don’t argue with them past a certain point. But I feel it’s my job to attempt to influence their thinking. OK, the director makes the movie. But some movies can’t get made without someone like me in them. You can’t call yourself an auteur if you want Robert Duvall for a part but you wind up with Jeff Goldblum. In that sense, Pirandello has begun to rule your life.

Looking over all of it, the single most obvious thing to me, in all we read and all we write about films, is this: people fear the creative moment. That’s why they talk so long about a given scene. But the creative moment is happening when the camera is turned on, and stops when it’s turned off. First time…this time…only now…never again to be that way again. That’s it.

One person cannot be in charge of all that. The director says when to turn on the camera, whether to do another take, and he selects which of the moments he thinks is worthwhile. From a collage point of view, he is primary. Bernardo [Bertolucci] and I heard this argued once, at seven in the morning, by Pasolini and a man who was head of film at the Sorbonne. The argument was this: In film syntax, what is the basic unit, the shot or the content of the shot?

In that sense, you can’t separate out the actor. With Michelangelo [Antonioni], the actor is moving space. If he wants to be straight, Michelangelo will tell you up front that the actor is not the most important thing in his movies. The actor informs the rest of the image, but it is the entire image which interests Antonioni. Another director might say that it’s only the moment when somebody touches their lip, or one hair is sticking out of place in a love scene.

I always try to get into whatever mold a director has in mind, but in all honesty, in the real action of it, they don’t know. They want you to deliver “it.” They hire someone like myself because they hope I’ll do something beyond whatever they have in mind. Bring something they didn’t write. They’ve created everything up to that moment when they turn on the camera—the clothes, the day, the time—but when that rolls they’re totally at the mercy of the actor.

Many auteurs are more fascinated by individual stars. They sense something in the star they want to use, like a color on a palette.

Oh, have I found that out! And I’ll tell you why: because a star is not a manipulated image. Nobody can prove that better than I. Only that audience out there, that audience which I’m not a terribly affectionate person toward, as you know, makes a star. It’s up to them. You can’t do anything about it, or I never would’ve got anywhere. Stars would all be Louis B. Mayer’s cousins if you could make ‘em up.

And that’s what those directors love, because they’ve studied or written every type of scene from every angle. I’ve been over every goddamned type of scene, either by myself or with somebody, and I don’t want to make a nice movie that’s like a great play. I want to make “that other thing.” Rafelson’s shooting the goodbye scenes; the wind blows, and a bird flies through. It’s the oddest thing of all time. Not planned. The audience may not realize it consciously, but somehow they know that is what made the scene right. The written scene is “I love you.” The bird is on his own.

When I was young, I was even further out. I was ready to make a movie about doors opening and closing for two hours. Sometimes I wanted to stand up and shout, “Didn’t you hear Godard? All you want to talk about is story. You think that’s it.

Before I moved into the mainstream of American movies, I wrote a script as an experiment. I wanted to get very far away from the clichés about the three-act play—structure, development. I refused to think about it except when I was sitting at the typewriter. I wanted every day to inform the script. The end came when I had written 94 pages, which I considered the magic number in those days.

What was the script like?

Great!

What happened to it?

I don’t know, I lost track of it. Last year, somebody tried to buy the first script I ever wrote for a lot of money, but I couldn’t find a copy of it either.

Prizzi’s Honor

Prizzi’s Honor was something of a family affair. Did you have any qualms about doing it?

I had trepidations. I’ve always tried to do what was best and not what was convenient. The pre-picture anxieties were very intense because the deal was difficult to make and the diplomacy of the situation quite complicated. But once it got rolling, it definitely had the flavor of a family project. That doesn’t necessarily mean that it informs the doing of the film—other than that Prizzi is about a family. John Huston and John Foreman have been close for years, and I’ve been Anjelica’s boyfriend for quite a while. I knew John Huston even before I knew Anjelica, and I always wanted to work with him; we’d talked intermittently about different projects.

How did it all work out, finally?

It jumped into gear pretty early on, and it was fun. I have been silently hoping for Anjelica’s success as an actress, and I’m very happy that it is beginning in a picture we worked on together. Prizzi should be a career-maker for her; she is flawless in it. And in the real world, it was a big deal for her and John to work so successfully together. There was a lot of grit between them on the subject of A Walk With Love and Death. They seemed to have had two separate experiences, equally baffling to both of them. But it was obvious how exhilarated John was by the material and by how much she has grown as an actress. She reacted to that, of course, so it did give the experience a special quality.

Did the filmmaking affect the intimacy among all of you?

Anjelica and I decided to have separate apartments in New York—which is what we do in real life, too. It was just a professional thing: different hours, calls, places to throw your notes. As far as my relationship with John Huston is concerned, we have always gotten along very well. I don’t know anybody who’s as well loved as John Huston. It’s quite a phenomenal thing to see. Teamsters stand up when he walks by. They’re proud to be called “shiny pants” because they never get off their asses, so the fact they stand up is a singular compliment.

Once you started working with him, were there any surprises?

The biggest surprise is that he’s totally unique. I knew a lot and I’d heard a lot but I wasn’t ready for “total unique.” It’s in the way he commands a set, the economy of his shooting, how he approaches the work, what he’s after, how sure he is of what he’s after. I did more one-takes on this picture than anything since my Roger Corman days!

John camera cuts. If you only do one take you don’t really know what you did. You don’t get to refine it. You come home and think of the 35 things you might’ve thrown in the stew. When a director shoots several takes, you eventually find his rhythm and try to come up to the boil together. But with John Huston everybody’s got to be ready to go right away. But there were never any problems. Everyone ha such respect for him that no one want to be the fly-in-the-ointment, so to speak.

Richard Condon’s novel verges on the surrealistic. How did you approach it?

Initially, I did not understand it. I did not know it was a comedy the first few times through, including having read the novel. I thought the jokes were what needed to be rewritten, and I kept saying, “John, this is gonna get a laugh, y’know.”

Then he said [perfectly imitating Huston’s speech] ‘‘Well, you know it’s a comedy.” Once I got that straightened out, I got going.

What kind of dialogue did you have with Huston about your character, Charley Partanna?

I was down in Puerto Vallarta for a week but about all we did was watch the boxing matches on the Olympics twelve hours a day. The business talk was very brief. After I found out it was a comedy, I went back to my room and read it over a few more times, and then came back and this is what he said to me: “It seems, Jack, that everything you’ve done until now has been intelligent. We can’t have any of that in this film. And I’ve got an idea, I hesitate to say what it is, but something to let people know immediately that Prizzi’s Honor is…different…from anything else you’ve done. I hesitate to say it, but I think you should wear a wig.”

Now I’ve got comedy…and dumb…and a wig to deal with. I went to bed.

Carnal Knowledge

What kind of wig did he have in mind?

A bad one. I’ve never worn a wig except in Carnal Knowledge for the teenage stuff, but I’ve always thought of it as an aging device rather than the reverse. If you do it just a little wrong, it makes you look older. So, while I was ready to wear this wig John had in mind, I was definitely searching for something else to make the same point. Some friends of mine who grew up in Brooklyn took John and me out and about in the “environment” there, and one day I came up with this little device…[curls his lips as he does throughout the film]…which helped me talk funny, too. [He launches into a pronounced Brooklyn accent.] One small thing like that can give you the spine of a character.

Was it an actual prosthetic device?

No. I’m not going to tell you how I did it! One day in the limo I tried it out on him and he said, ‘Oh, that’s fine, no wig.’ I noticed that Sicilians and Italians don’t move their upper lips much when they speak. I was mainly worried about playing an Italian. I turned down the original Godfather because I thought it should’ve been played by an Italian. I both do and don’t regret that decision, but I know it was right. Al Pacino was the perfect actor for it and the picture’s better because of him. But now a little time has passed and it’s not so militant, so I thought I could get away with playing an Italian. And the lip curl and accent really gave me as much of a feeling of being a different nationality as it aided the comedic aspect.

How did the accent evolve?

One day in New York, Anjelica and I were huddled in our hotel room when John called. “Kids, I’ve found some wonderful stuff; I’ll be right over.” And he shortly came running in and said, “Have you ever heard true Brooklynese?” I told him I thought I had but I wasn’t sure, and he said, “I’m not sure you have either. We’ve all got to go back to school for this picture. This is the way we’re all going to talk, this is what we’ve been looking for.”

He brought in Julie Bavasso and told her to read us some of the script—which she did and left. John was enthralled. “Marvelous, wasn’t it, marvelous.” Then he stood up and went over to the window and looked out on Central Park and said, “Oh, look at the city here. It’s one of the world’s beautiful sights, isn’t it? Well, see you later, kids.” And he was gone. That was it for Brooklynese until we were all out in Brooklyn, makin’ the movie, looking and listening. When you use a dialect, you worry that the people you’re imitating will think you’re making fun of them. But we eventually got it together.

Can you compare Prizzi’s Honor with anything else you’ve done?

Nothing. The closest would be to pictures where I’ve been extreme, such as Goin’ South, The King of Marvin Gardens, and maybe The Missouri Breaks. These movies haven’t always gone down too well with the public but, oddly, I think they’re what is most successful about my career as a whole. Many actors will try something different once, but if it isn’t a box office success they’ll never do it again. In my opinion, there’s no point in going on with this job if you do the same thing over and over again. I feel very lucky because I don’t think there’s any part I can’t play. There are parts that scare me more than others…

Didn’t Charley Partanna scare you a little?

Only in the sense that I’m used to working within a very informed team concept. Having come in so dumb, I was worried. What John said that finally brought me around was “I always hesitate to say this, Jack, but I think we have a chance here to do something different.” When John Huston says something like that under the weeds in Mexico, well…

After you’ve made a movie or two, and you’re over the feeling that you’re hanging onto something ephemeral by your fingernails, the fun of doing it is in the difference of it. I’ve always been a smart-aleck filmmaker. From ‘way too early on, I thought I knew everything, so the opaqueness of Prizzi s Honor took me by surprise. But I used it. I put my not understanding the material together with the character’s dumbness into a kind of dynamic on how to play him. I let the character’s limitations keep me happy.

For example, I did not want to know what period the film was set in and I didn’t try for the same kind of dialogue with John that I do with other directors. When you bring him an idea, he doesn’t say he don’t like it. He just goes [big tooth gnashing grimace]…and that’s all he has to do. You never bring up the idea again. You drift off like smoke.

So I said to myself, “Okay, I’ve got one of the most commanding people I’ve ever known with his hand on the helm; the producer’s an old friend of mine; I’ll just do my own simple job like a dummy and that’s it.”

Prizzi’s Honor

What do you think Huston meant when he used the word “different” in relation to Prizzi’s Honor?

We’re in a time when high concept is king and Prizzi’s Honor is not about high concept. It’ about alleys and place that people haven’t gone before. I think it’s very revealing of the milieu that it’s about. After all, Italian are funny people. But you don’t want to gamble with them a lot; they can also be dark. I don’t know any professional gangsters, but I would imagine they’d find Prizzi most entertaining. As you know, I’m a big peer-group pleaser. They may be able to look at it and enjoy it, and that is what successful satirical comedy is all about.

Tell me about Two Jakes—is it a genuine sequel to Chinatown?

Not exactly: We always had the idea of three film in the back of our minds, but at the time of Chinatown’s release [1974], sequels weren’t a big part of the industry. The first story began in 1937—which is the year of my birth—and follows my character eleven years later after he’s been through the war. That’s 1948; and the third story finishes off at about the time Robert [Towne] and I actually met.

In other words, it’s a literary contrivance; an 18-year project. We wanted to do a project whereby you waited the real amount of time that passed between the stories before going forward. That’s why we never talked about a sequel; why we negotiated a contract wherein they couldn’t make one without us—they couldn’t do a TV series. I don’t have to gray my hair for Two Jakes because eleven years have passed and I played the part before and this is what I look like eleven years later. Cinematically it works.

Statistically, people’s careers don’t last 18 years, so to plan an 18-year project is insane. But we’re almost half-way there now. The next one, to represent 1953, which is just before Robert and I met, will be five years from now. They deal with Big Elements: air, land, water, fire. I’m demi-collaborative in all of it. Bob’s doing the writing—and he’s definitely in the running as the great screenwriter of our time—but we’re partners. I’m the vehicle. The risk we take is that no one will want to see the third movie. You got to have a little trust.

Robert always wanted, as a literary trick, to create a new and original detective character like someone from Hammett or Chandler. It kind of begs the notion of a sequel. And, for his part, as a native Californian, to tell the social history of the region. It’s the roman à clef approach.

Robert always teases me because I want to call it a triptych rather than a trilogy because I always wanted the movies to stand on their own, yet be able to be seen as a group. And he does too. But he teases me because I use a painting rather than a literary term.

Triptych is also non-linear…

That’s right. You can put one piece in Asia and the other in Brooklyn and people don’t even know they’re part of a trip or diptych or whatever. It’s a big piece of writing. RT is a dear friend and whenever the opportunity arises—as it did on Chinatown and The Last Detail—we’re inspired to work together. And that’s the fun of it; that’s part of the fun of lasting.

You have to do every movie one at a time. Trilogy is contrary to this ideology. My nightmare is to wake up and find myself the host of a TV series—GE Theatre, for instance.

What is the status of Mosquito Coast?

I was committed to it as long as they wanted me to be committed, but they weren’t able to put it into production for one reason or another.

And The Murder of Napoleon?

I have a lot of collaborators, but no partners; I work on my own. I’m doing what is called producer’s work on it. Bob wanted to write and direct it but that effort has branched into Two Jakes. I haven’t gone to a studio and said I’d like to develop it, because I’m working all the time. And no one has asked me. I feel just like I did as an actor early on. I don’t understand why nobody is asking me to direct films or to develop projects.