Interview: Ilya Khrzhanovsky

Ostensibly, Dau, the much-anticipated multimedia project by Russian director Ilya Khrzhanovsky, is a film, or a series of films. But it also claims to be something more: as the publicity material puts it, “a pluridisciplinary epic project,” existing “at the intersection of film, science, performance, spirituality, social and artistic experimentation, literature, and architecture.” Maybe the standard criteria of cinema don’t apply; standard moviemaking methods certainly don’t.

Dau premiered in January in Paris, trailing a uniquely enigmatic backstory. In 2006, Khrzhanovsky began work on his second feature, conceived as a biopic of the Nobel-winning Soviet physicist Lev Landau (1908-1968). But Khrzhanovsky decided that the project needed to be more ambitious: the film, called Dau after its fictional central figure, would span several decades and the production would involve the building, near Kharkov in Ukraine, of a massive space representing the research center where Dau, his family, and his colleagues lived for 30 years.

What became known as the “Institute” wasn’t just a set, but a self-contained building in which the film’s participants—several hundred of them—cohabited full-time over the Institute’s three-year existence, required to live, work, dress, and eat in conditions that replicated Soviet times. The cast, nonprofessionals except for one actress, included real-life Russian scientists; various international luminaries, including artist Marina Abramović and opera director Peter Sellars, also spent time at the Institute.

Dau became the stuff of legend, largely thanks to a 2011 set report in GQ. Year after year, cinephiles wondered when Dau would appear at a major festival; year after year, it failed to materialize. Legendary for its grandeur, the project was compared both to Apocalypse Now and to TV reality shows. The idea of creating an entire self-enclosed universe that took on a reality of its own irresistibly recalled the ever-expanding soundstage-as-world in Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York.

Remarkably, Khrzhanovsky’s “Synecdograd” was not the project of a powerful, seasoned auteur; it’s very different, say, from the somewhat more moderate, albeit wildly eccentric project The Tulse Luper Suitcases undertaken by Peter Greenaway over a decade ago, which resulted in four feature films and a traveling exhibition and came across as a grand culmination of a long and eccentric career. By contrast, Khrzhanovsky had made just one previous feature, the fascinating but esoteric 4, a nightmare portrait of modern Russia written by the conceptual novelist Vladimir Sorokin. How on earth, then, did he persuade people to get involved, and to finance him?

“You’ll understand when you meet him,” Dau’s executive producer Martine d’Anglejan-Chatillon says on my visit. “Perhaps.”

The above is an excerpt from Jonathan Romney’s feature on Dau in the March-April 2019 issue of Film Comment. Read Romney’s conversation with Khrzhanovsky below.

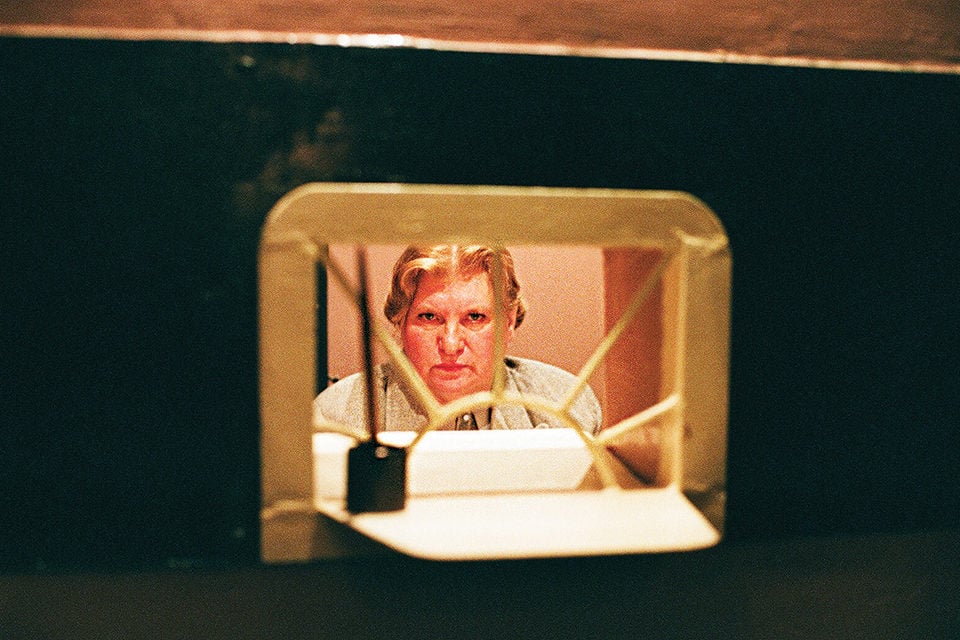

DAU, © Phenomen IP 2019, Photo by Olympia Orlova

So you see the Dau films as trailers for the online material?

The films themselves are trailers for the matrix: it’s more a way to introduce the characters and the stories. For this “event”—I don’t like this word—we knew we needed a space where the audience would have enough physical time and enough space to learn and react to the movies, and spend the right time between the movies, before and after.

After watching four films, I realized that watching Dau wasn’t really about piecing together a narrative, but more about exploring its world.

Most of them have the shape of a movie, but it was important for me to keep this raw feeling—that’s why we chose theaters under construction. One life is finished, another life didn’t start yet. It’s raw—you can never make it beautiful and comfortable, it’s a kind of station in between.

Was Dau originally conceived as a “normal” film, and how did it become something else?

The kind-of-normal film will arrive later—the “mother movie,” let’s say. There will be one, but with completely different rules. But I want to talk about the present time, and to do that you have to go out of the present. My options were fantasy, fairy tale, past, [or] future, but the Soviet past I know—it’s this kind of trauma that all of us who grew up in the USSR have, whether we accept it or not. Or maybe not trauma, but some specialty of perception of the world. Also, it’s a kind of magic thing that there was a big country which has disappeared. People were born in cities that don’t exist anymore, like Leningrad. The idea is to really create a world that has never existed before. Of course, what we’re creating is a fantasy.

Your first film 4 contained many fantastical elements. Here there are very few traces of the surreal.

You just didn’t see them. There are some completely crazy, surreal stories, but you never know where is this border between real and surreal—not only in art, but in politics and technology. What can be more surreal than quantum physics? If you start to think about a nonlinear world, then you don’t know how to react—everything you think is real is not.

DAU, © Phenomen IP 2019, Photo by Olympia Orlova

In some ways, the drama in these films feels much closer to theater than cinema.

Theater is more life. What is cinema? Now everybody is a cinematographer, everybody films something on his own telephone. What I’m doing, I don’t know—is it cinema? Yes, because I film it, and the main engine [behind it]was cinema. Is it theater? In the moment when you’re coming inside the performance, yes—it’s an ongoing thing, if you visit this theater. Is it performance? Yes. Is it contemporary art? Probably yes. But I never think what kind of area [the project belongs in]—it’s between everything.

How do you get your nonprofessional cast to lose their inhibitions—particularly in sex scenes, where there’s no restraint?

This was a space where things happened with people and they just reacted to each other. Part of it was sex, part of it was intellectual conversations, part of it was drink, sleep, food. Sex is probably not more than 10 percent of the whole material.

Everything was shot on 35mm. No hidden cameras, no hidden recording, ever. You have [the] camera, you have [a] focus puller, [a] boom operator… I love that a lot of people think it is real, that the rape is real, the torture is real. The emotion, of course, is real—but it’s real inside this world.

Initially I wanted to film actors. But actors can only play on the psychological level. When I started to invite people with a different human structure [to perform], I tried to bring together personalities. Some people, you talk to them and you know that they’re not alive anymore—they can be successful, they can be funny, they can be lucky, but you know that something in them is dead. Big personalities react differently—they’re not predictable.

Read Jonathan Romney’s full feature on Dau in the March-April 2019 issue of Film Comment.