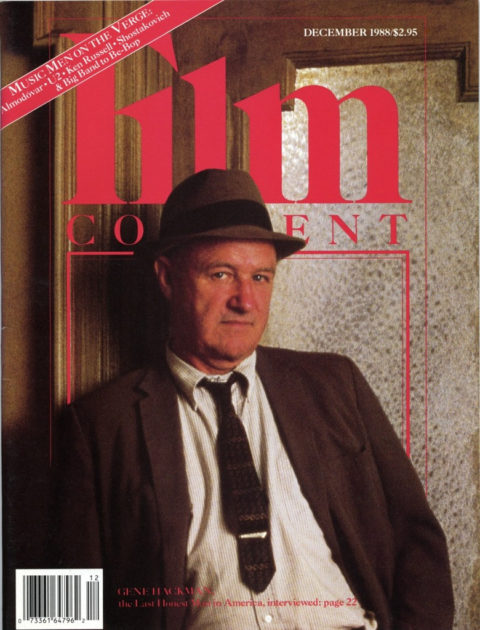

Interview: Gene Hackman

If recent films are an indication, Gene Hackman is entering a whole new phase of his already remarkable career—as a late-blooming romantic leading man.

The most riveting scenes in three of his upcoming films are with women—even in such an unlikely vehicle as Mississippi Burning, the searing drama directed by Alan Parker in which he and Willem Dafoe play FBI agents investigating the murder of three civil rights workers in 1964. Hackman’s gallant approach to Frances McDormand, who, as wife to the deputy sheriff, knows, literally, where the bodies are buried, is something to behold—tender, warm, and subtly sexual.

In Full Moon in Blue Water he plays a moping widower who is simply lost without a woman by his side, and in Woody Allen’s Another Woman, opposte Gene Rowalnds, his juicy, masculine charm is palpable. The surest sign we’re given of Rowlands’ character’s misguided life is her rejection of Hackman.

No other American actor is doing this kind of work. Indeed, civilized relations between the sexes have been largely absent from our films for 15 years—lost to the youth craze, buddy movies, and confusions brought on by women’s emergence from the kitchen and into society at large.

All the more remarkable, then, to find need, caring, and delicate sensuality embodied in an actor who in 1971 became a veritable icon of blue-collar machismo with his Oscar-winning portrayal of the obsesses narcotics cop, Popeye Doyle, in The French Connection. Not that Hackman has been totally confined to working-class trenches. He was a surveillance expert in The Conversation, a skydiver in Gypsy Moths, and a labor organizer in Reds. He did brilliant comic turns in Young Frankenstein and the Superman movies, and in the Eighties has risen to white-collar ranks, playing an arrogant defense secretary in No Way Out, a ruthlessly effective campaign manager in the underrated—and prescient—Power, and a confident, privilged foreign correspondent in Under Fire. In Nicolas Roeg’s Eureka, he combined marginal man with tycoon, as a gold prospector who strikes it rich and becomes a megalomaniacal island potentate.

But all of these films required Hackman to play the quintessential man’s man for whom women were mostly a diversion—often a troublesome one—if they were even around at all.

Director Arthur Penn thinks the roots of this metamorphosis may be seen in Night Moves, the 1975 thriller they made together where Hackman has tough, sexy scenes with Jennifer Warren. Perhaps. Certainly by the time of Under Fire (1983) in which he endures humiliation rather than relinquish a woman he loves to another man; Twice in a Lifetime (1985) where his steelworker agonizingly terminates a 30-year marriage for a woman of his wife’s generation (Ellen Burstyn and Ann-Margret co-starred); Hoosiers (1986) and his ardent wooing of Barbara Hershey; and even in No Way Out where carnality and male pride lead to murder, it was obvious that something fresh and potent was emerging.

Eugene Alden Hackman was born January 30, 1931 in San Bernardino, California. His father, a newspaper pressman, moved the family to Danville, Illinois—abandoning them when Hacjman was just 13. At 16, he lied about his age and joined the Marines, servining in China, Japan, and Hawaii. He got his first taste of show business in Armed Forces Radio, as a deejay and newscaster.

He briefly studied journalism at the University of Illinois (his grandfather had been a veteran journalist) and then hitchhiked to New York to attend the School of Radio Technique under the GI Bill. He worked in radio stations around the country for a few years and then returned to his birth state to study acting at the Pasadena Playhouse. Fellow classmates included Dustin Hoffman and Ruth Buzzi.

Returning to New York in 1956, he got work relatively quickly in summer stock, off-Broadway, and live television. A turning point came in 1963 when he won the Clarence Derwent Award for Irwin Shaw’s Children at Their Games, a production which lasted all of one night.

The hit comedy Any Wednesday, in which he co-starred opposite Sandy Dennis in 1964, established his Broadway reputation. Shortly thereafter, he won his first substantial film role, in Lilith, which starred Warren Beatty, who was responsible for Hackman’s being cast as his brother in Bonnie and Clyde. It was the first of three films he made for Penn (Night Moves, and Target in 1985), and earned him his first Oscar nomination in the supporting category. The second came two years later for I Never Sang For My Father, and two years later came The French Connection.

Altogether, Hackman has made an even 50 films, and though many have been routine, his contribution has always been of the highest order. “He is incapable of bad work,” says his Mississippi Burning director, Alan Parker. “Every direct has a short list of actors he’d die to work with, and I’ll bet Gene’s on every one.”

“He is an extraordinarily truthful actor,” comments Arthur Penn, “and he has the skill to tap into hidden emotions that many of us cover over or hide—and it’s not just skill but courage.”

The range of raw emotion, feeling, states of being and conflict Hackman can convey is remarkable. His face is a great instrument. His body still as a statue, we watch his face, the interplay between his mouth and eyes. He allows us inside; we are really with him, we see the decision process and thus are prepared for the final thrust of his action.

This great gift is of particular importance when he acts with women, because often the action there is internal rather than external, which is why he has been tapped for some of these recent roles.

“American movies have always had certain kinds of self-styled actors who shouldn’t be stars but are,” notes Penn, “and Gene is in the company of Bogart, Tracy, and Cagney.” The director agrees that Hackman is more than ready to bust loose of his average-Joe trappings and do something on a grand scale—a modern-day Coriolanus or Lear.

Two projects are already set for next year. In The Package, directed by Andy Davis for Orion Pictures, he plays a career master sergeant inadvertently implicated in a conspiracy. Then Hackman makes his directorial debut with Thomas Harris’ best-selling novel, The Silence of the Lambs, also for Orion.

There is an ageless quality to Hackman; he has changed little in 14 years and is more at ease with himself than ever. He attributes the new dimensions of his artistry to conscious acting choices rather than to an altered states as a person. “In a way, something is just beginning for him,” says Penn.

Gene Hackman and Frances McDormand in Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988)

This is an exceptionally active period for you as an actor, and you have lots of choice. Why Mississippi Burning?

I suppose I see myself as a serious artist, and it felt right to do something of historical import. It was an extremely intense experience, both the content of the film and the making of it in Mississippi. I was dubious about shooting it there, but Alan thought it would be a cop-out not to, and he kept an edge on the project that was very valuable. As it turned out, we didn’t have much trouble, but there is, of course, still sensitivity.

Didn’t the original script center almost totally on the relationship between the two FBI agents?

Yes, and I had some initial reservations, fearing an exploitation of the incident. Before I accepted the project, much of that was fixed. It’s really the story of how two guys from totally different backgrounds work out their relationship in the process of solving a problem—in this instance the violation of civil rights, and murder. I suppose it’s the difference between a right-wing Republican and a fairly liberal Democrat—though we never discussed politics. My character is a former sheriff from Mississippi and Dafoe’s is more Northeastern oriented and academic.

It’s possible to see your character two ways—with racist tinges, or as someone who has risen above it but who understands and has compassion for these people and the problems of the region.

The FBI man in charge of the actual case was from Mississippi, which may have provided the movie parallel. My character did understand the regional attitudes, but he was definitely not a racist.

How much of the character’s background was in the script, and how much did you create for yourself?

There are just a few biographical type lines. One builds the rest along with the director. As an actor, you hope that you make the character come to life and understandable, without resorting to a lot of exposition, which can be boring.

I read everything I could get my hands on about that period and the incident, including the book Three Lives for Mississippi. In a curious way, I got a lot of insight from a book called The Selling of Marcus Dupree, which paralleled the life of a black football player born on or near the day of the murders. It was done in such a way as to imply that the civil rights workers’ deaths were not in vain: They died so that he could live.

There was a woman there who fought for years to get the case before the proper authorities, and she ended up losing most of what she owned. They froze her out. Everything I learned helped me shape the character in small and subtle ways. I didn’t spend much time on the accent because I did not want it too strong—country rather than Southern. Otherwise it would get in the way.

Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe in Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988)

There’s a certain ambiguity in your relationship with the deputy sheriff’s wife (actress Frances McDormand). Was your character coming on to her just to get information, or was he attracted as well?

Originally, Alan wanted me to make love to her right then, on the floor of her house. I felt that was excessive and would distract from her as a human being and from her courage in terms of what has just revealed. She didn’t do it because she wanted to make love to me but because she thought it was right.

We finally agreed that the lovemaking would be left out, but perhaps the ambiguity comes from Parker’s wanting some of that feeling to remain. I never quite resolved the conflict in my own head. I felt he did care for her a lot, and in the end made a decision to just let her be, not to complicate her life further.

How do you play what I’ll call a double action like that? You’re sweet-talking this woman, and though you may like her, you’re really there to solicit information. There’s something similar in The French Connection, when you publicly rough up a black guy who is actually your informant.

You cannot play a lie. You must play some kind of truth, and if you make the right choice, the audience will read it right.

You mean you count on the film’s montage to give the right information?

Yes.

That takes a lot of single-mindedness, doesn’t it?

That’s right, and trust. That’s why it takes most actors at least ten years to have a maturity about what they do. You have to keep separating the wheat from the chaff, so to speak, to know what’s important and what isn’t, to understand certain physicality and energy.

It’s interesting she would say that because I think it is one of the most crucially important things to know about yourself. But most actors don’t want to deal with that—it’s too out front. They feel they should deal with what’s inside. That the intellectual side of acting shouldn’t exist, that it should all be right-brain function. But I’m a great believer in using both sides of the brain in approaching any art…painting or music…because the left-brain gives you the classical sense.

Referring to your beginnings at the Pasadena Playhouse, it is preposterous that you can Dustin Hoffman were considered “least likely to succeed.” It must’ve had something to do with your unconventional looks rather than with any lack of ability.

I think it did. Dustin was thought of as amusing and strange. He was called a “beatnik” because he wore a leather vest and sandals, which was outrageous then. I’d been in the Marine Corps for five years and was married—an equally unlikely candidate for movie stardom. I think that’s what drew us together. We became very close, and he lived with my wife and me for a while after coming to New York.

Neither Dustin nor myself looked like the leading men of that era, especially Dusty because he wasn’t tall. We were constantly told by acting teachers and casting directors that we were “character” actors. The world “character” denotes something less than attractive. This was drummed into us. I accepted the limitation, of always being the third or fourth guy down, and my goals were tiny. But I still wanted to be an actor.

It took guts to move forward toward an acting career at age 30-plus, with a wife but without encouragement. You must’ve had some kind of inner confidence or perhaps inner need that overwhelmed everything—your own fear and the stereotyping of others.

I had a little of both. Once I met the acting teacher I got the most from, George Morrison, and I started working twice a week with him on scene study, I got over a certain kind of terror. I started realizing that what I was saying to the other actor was very important, not only to them but to me as well. I don’t mean that I personally felt important. But at that moment of interaction there was a very concentrated sense of energy, and of connection, that felt great. I didn’t know if it was acting…I didn’t know what it was but it was thrilling. And I didn’t want to touch it, to examine it too closely—just to do it.

So it was finding that sense of brimming over with the life force that did it for you?

Yes. Actors tend to be shy people. There is perhaps a component of hostility in that shyness, and to reach a point where you don’t deal with others in a hostile or angry way, you choose this medium for yourself.

A surrogate personality.

Absolutely. Then you can express yourself and get this wonderful feedback.

In previous interviews, you’ve indicated that you were headed for the stage rather than films or TV. Why?

In the theater you can play characters totally different from your persona with the aid of make-up, costumes, and so on. In films, you’re pretty much limited to your type. In recognizing what was exploitable about myself, what would get me a job, I chose theater. I was still thinking in terms of conventional leading men in films. Brando had made his mark, so there was something of a groundswell about men who didn’t have conventionally handsome faces, but it hadn’t totally happened.

But it has by today, hasn’t it?

Yes. Conventional handsomeness is almost a deterrent now.

French Connection II (John Frankenheimer, 1975)

The French Connection was the real springboard for your career. Did you have any idea it would become such a hit?

No, no one did, including 20th Century-Fox.

I’ve read you were quite conflicted during the filming because you found it difficult to play the violence.

That’s so. We shot in continuity, and on the second day I caught a black pusher in the alley and had to pop him in the face. The scene was originally shot in a squad car, with Roy Scheider and myself taking turns hitting him. I’d never had to do anything like that before. True, I’d done my share of fighting as a kid and I’d been in the Marine Corps, but as an actor I’d been taught that relaxation was of utmost importance, and I was not relaxing during that scene. In fact, I felt terrible, and the scene was no good. That night, I told Billy Friedkin he should consider replacing me. It was naïve of me to propose such an idea, but I was serious.

And what happened?

Billy said we’d talk about it later and continued to shoot. About the end of the first week, something clicked in my mind which brought the whole character to life for me and ended the conflict. I’d seen Eddie Egan, the real-life cop the character is based on, dipping a cruller into a cup of coffee and then pitching it over his head. There was something in his attitude that made everything very clear: This guy doesn’t give a shit about anything except his work; he is totally directed.

During the last week of filming, we re-shot the earlier scene except, we did it in an alley. By then I understood my character and could do the action with a certain fullness. When you do it like that, you communicate something to the other actor—Alan Weeks, a dancer—which is that you’re acting and not really hurting him. It was like magic.

And have you subsequently had problems portraying violence?

Always. I always have to find a way to do it. I listen to stunt guys, and I’m very careful; I insist it be totally choreographed. Still, it’s always hard for me, perhaps because there’s such a contradiction between fighting and the craft of acting. If you really fight somebody in a scene, it negates your craft. And since I’m only interested in my craft, it has to be resolved anew each time.

How’d you get that hat you wear throughout The French Connection?

Oh, I saw it in wardrobe one day and put it on.

It was way too small for you.

Oh, yes. That was why I liked it.

When you made I Never Sang for My Father, was your personal relationship with Melvyn Douglas affected by your mutual fictional roles of warring father and son?

The opposite. I had admired Melvyn so much as an actor, but he didn’t like me. During the filming, I inadvertently found out that he had actually warned someone else. This hurt me, but it certainly added to the tension in the film. We kept away from each other, rarely spoke.

The character I played was actually similar to my own father who, as opposed to Melvyn’s character, was not a real strong guy. So it was strange. At a tribute last month in Las Vegas, I avoided looking at a clip from the picture.

What considerations go into accepting or rejecting a given project?

The overall screenplay first, then the character proposed to me, and after that the director and other actors—almost always in that order. Of course, in the Seventies I took a couple of pictures because of the locale….

Gene Hackman and Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

Gene Hackman and Teri Garr in Full Moon in Blue Water (Peter Masterson, 1988)

Full Moon in Blue Water has some extremely funny sequences. You and Teri Garr work well together.

It was worth doing the whole picture for just one scene I have with Teri, a big argument where I chased her around and called her a “whoor.” I loved it!

How do you manage to work at such a pitch, both in terms of quantity and quality?

I have a terrible need to excel at this thing I’ve chosen to do, and I keep wanting further challenges. Unfortunately, in film one is cast so close to type, and I keep getting offered similar roles. But within that context I try to find a way to do something a little different.

Tell me more about this influential acting teacher, George Morrison.

I was introduced to him by Ulu Grosbard, who directed me in my first summer stock production, A View from the Bridge. They’d been at Yale together, and Morrison was already teaching. He was very important for me. He was extremely sensitive and saw in me…something. He never said anything, like, “Gene, you’re a great talent,” but I had a sense he cared. Of course, he gave this caring to others as well, but for some reason I took it personally. His teaching was simple and understandable, something I could get my teeth into.

Will you describe your technique?

[Smiling indulgently, it seems] I do the same thing now was when I was just starting, I ask myself a few questions: How is this character like me? How is he unlike me? In the difference between these two, what is important? What choices can I make which will further the author’s intent? I ask myself where, when, why—real simple questions. I do an atmospheric kind of thing by dealing with objects such as where I’ve been when I come into a room, where I’m going when I leave it. Before every scene, I still do the same relaxation exercises George taught me 20-odd years ago. First-year acting tasks. Those work for me.

Of course, you can’t do just that. You have to make good choices and do a lot of technical things, too. It took ten years for me to fill up as a person, but once I became mature all of that kicked in in a simple, direct way.

Arthur Penn has spoken of the surprises you bring as an actor. He mentioned your death scene in Bonnie and Clyde, when he had suggested an image of a dying bull. How did you work with that image, and have you worked with other images?

I had seen some bullfights. In my motel room, I worked on all fours, trying to emulate the movements of a bull that had been wounded in the back of the neck and is dying.

I love animal images, but I’m so often cast as a working man, and when have we seen a working man who is, for example, a tiger?

How do you feel about other actors who try to physically inhabit a character? Like De Niro putting on weight for Raging Bull?

I love Bobby De Niro for taking those kinds of chances. It’s hard to describe the pressure of being on a movie set with ten million dollars or more riding on your performance. It’s terrible for an actor to have to deal with that, but it’s a reality and you know it. For De Niro to take on that kind of a character problem is very exciting for most actors. I can’t imagine anyone saying he was over the top or whatever. It was brilliant. I’d love to be given a role with that kind of challenge.

You’d be willing to do something like that?

Yeah. [smiling] I don’t have any problem gaining weight.

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

You’ve said in previous interviews that The Conversation was an important film for you, as was its director, Francis Coppola.

I’m always asked about Francis, and I always say it was one of the most interesting working relationships I’ve ever had. But in thinking back about it, I can’t remember anything in particular he ever said. He created ambience which is very good for an actor, the most important thing. You never have a sense he’s dissatisfied or that what you’ve done is not enough, or is too much…He’s just there.

Did you ever have a sense there was an autobiographical component to the film for him? Maybe not factual so much as spiritual and emotional. In The Conversation, the wiretapper lived his life “voyeuristically,” talks about being paralyzed by polio, left in the bath by his mother, and nearly drowning. Coppola may not have experienced all those things, but he did have polio….

There did seem to be something special about his relationship to the film, but I assumed it was just the way he typically worked. And I’ve never done a film with him since, though he has asked me a couple of times and we couldn’t work it out.

Coppola is a very mysterious man—extremely sensitive and yet with a certain kind of bluntness, possessing a great joy of life, but there is a dark side, too.

I could tell the film was very important to him. But when the shooting was over he walked away from it like it was a piece of dead meat. He had to be in New York to start Godfather II.

At the time, I recall hearing that major restructuring work was done in the editing room. Was the finished film very different from the script?

No. I think what people talked about was moments.

Are other actors important to you?

Very. It’s almost everything, once you’re on the set. The people in a scene together have to create an atmosphere to make it work. Today the hardest thing for me is to be patient with younger actors. I tend to forget I’ve been doing this for 30 years, and some of it is very easy for me. Being there, hitting marks.

Is it the technical part you’re impatient with?

I catch myself wanting to say—though I’ve never said it—“Try it another way…turn it upside down…do a 180 on it,” or whatever it takes. I watch actors in a real funk because they can’t make something work. I know how to make it happen for them, but I can’t say anything because it’s not my place. It’s a directorial prerogative, which is what I’m going to go on to now.

How important is a director to you? I’ve read that you like to direct yourself.

Yes, I do. Since I didn’t have a strong father, I don’t have any authority problem and I cannot stand to have someone tell me how to modulate a scene. I’d rather a director say, “Can you find another way to do this—louder or softer or funnier?” If someone comes over to me and says—especially if I think he’s conning me—“I’m wondering if you should go over there to that chair, or not?” it sets me off. Since I’m in a performance state, I don’t want to have to deal with a lot of politics about whether or not I should go to a chair. I’d much rather the guy say, ‘It doesn’t work for us, can we try something else?’

You prefer to make the choice yourself?

Yes, then I can immediately see what the problem is and do something about it, as opposed to having to deal with some kind of diplomacy which I don’t think has a place in art. I understand the necessity of being courteous, but when your energy is real high and you’re trying to capture something, you don’t want someone dealing with you on another level. That’s usually where I have most of my problems with directors.

It’s difficult for a director to know what words they can say to an actor, especially if the scene’s not working and he’s a little defensive. You feel, probably because of ego, that you want to fix it yourself. It’s a very strange atmosphere to work in, and [laughing ruefully] I pity directors who work with me. I do try very hard to get along, however.

They must know by now what to expect.

I guess the word is out, yes….

You’ve made three with Arthur Penn—what makes the two of you such a good combo?

I think it’s because we both came out of theater, even though I haven’t been back in a long time. Our approach is theatrical in terms of a concern for how the overall price works. And we both have a lot of energy. I like to come on the set when I’m not in the scene just to watch him work, to see the kind of energy and enthusiasm he puts into his side of it.

I made a list of your films that stick out in terms of having a lasting impact. Most are from the early phase of your career because we can already see their place: Bonnie and Clyde, The French Connection, I Never Sang For My Father, The Conversation, Superman I and II, and possibly Under Fire and Night Moves. Twice in a Lifetime got significant new life in TV syndication and videocassettes and is increasingly written about.

I tend to agree with you, but actors have moments in films less commercially successful which they love. I had a scene with Candice Bergen in Bite the Bullet which is one of my favorites. I was telling her about my ex-wife, while standing around a waterhole in the middle of the desert. I played it on horseback.

I think some of my best work was in The French Connection, Part II—the withdrawal scene. I saw a lot of films on drug addiction and withdrawal, and I chose a specific pain for myself. Frankenheimer allowed me time to prepare for that kind of work in a class, when you’re in a protected situation, and another on asset where you’re incredibly limited by time and other restraints—it’s four in the morning and the crew has been there since six the previous morning, and people thin you’re being difficult because you need time to make the scene really come alive. The best actors can do it, though. An actor has to have a terrible toughness and sensitivity side by side.

Al Pacino and Gene Hackman in Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg, 1973)

Do you have a favorite movie in terms of your performance?

Yes, Scarecrow. It’s the only film I’ve ever made in absolute continuity, and that allowed me to take all kinds of chances and really build my character.

In the process of just living, most of us scar over—we almost have to. But if an actor allows that, it profoundly limits his artistry. Have you consciously kept yourself sensitive and vulnerable for the sake of your acting?

Most definitely. It’s one of the most difficult things an actor has to do, to keep himself sensitive, to watch behavior in others, to shut down the defense one has to have in the business end and shift immediately into the creative process.

How do you do it?

It’s a matter of concentration. I’ve developed it; most actors do. I can be incredibly angry about some business aspect of filmmaking and within 30 seconds be performing in a scene, having totally blocked it out.

The very process of acting is often one of regurgitating pain—how do you deal with that?

That’s the pleasure of the work. When you’re operating at your fullest as an actor, emotionally full—the scene is working, tears are flowing, and there’s a certain kind of warmth that suffuses you—nothing feels better!

When a painful scene is over, what do you do with yourself?

Well, there are a lot of practical considerations which you immediately have to think of. If you know that take was the one, and it’s over, you feel great. But there’s a beat when you say, “Do I have to do it again—maybe a close-up or a reverse angle?” If so, you must keep yourself contained. You find a little spot for yourself while they’re re-setting the camera. Stay close. And you do it again. If it felt really right the first time, it never feels as good the second.

How often do you feel your best take makes it to the screen?

I don’t bother myself with that. I decided long ago not to worry about other people’s taste in post-production.

You’ve said an actor can become better and fuller if he can give up a certain sense of his masculinity.

Yes. One of the attractive things in males is how much femininity they have in them—if they can reach it and deal with it.

Has that part of yourself become more available to you in recent years?

I think so, yes. I don’t think I’ve become more sensitive, but I’ve become more aware of what’s important. It’s really a matter of choice, as opposed to what’s available to me [from inside myself]. It’s a mellowness, a letting down of a macho idea.

There’s been a change in you that is reflected strongly in your face—many more layers of awareness and feeling and states of being, that you are now willing to reveal.

I think that’s why actors like Jimmy Dean and Laird Cregar were so amazing: they had all those layers, and yet they were so young. [Note: Laird Cregar was a physically imposing actor who died at the age of 28, having made an indelible mark in This Gun for Hire, Heaven Can Wait, and The Lodger.]

I do feel I’m getting better as an actor, but the clock is also running…Still, look at Ralph Richardson. In his last picture, Greystroke, he was so brilliant. He was always a wonderful actor, but there’s a difference between being wonderful and being great.

Marlon Brando. What is it about Brando?

He is our most sensitive actor and uses more of the feminine side of himself than anyone. Yet, he has tremendous masculinity.

Never have you been more warm, tender, sensuous, and male than in Another Woman. Every female I know who has seen it is talking about that!

I haven’t seen it. I didn’t read the script. Woody only sent me a few pages of dialogue.

Did you like that?

I did, surprisingly. There was no great responsibility. He just told me I was to play a writer from Santa Fe, and this woman—Gena Rowlands—was my ex-girlfriend. At the time, he didn’t know I was living in Santa Fe.