Interview: Dusan Makavejev

By far the most stimulating fare to be found at the Cannes Film Festival is at the youthful, politically unbiased Quinzaine des Realisateurs which programs films hardly conforming to the socio-political chic of the main event, or to the requirements of that other splinter festival, la Semaine de la Critique, which limits itself to seven features by new directors. The Quinzaine easily accommodates such disparate efforts as Marjoe and Celine et Julie, Bresson's Four Nights of a Dreamer and Schröter's Eikka Katappa. It is also here that the yearly succès de scandale usually takes place, before a large, young, unpaying audience enjoying a temporary surcease from the vigilance of the French censor. Last year, the odds favored Sweet Movie, a Canadian-French coproduction directed by Dusan Makavejev. There was considerable expectancy fanned by word-of-mouth reports that the film featured scenes of vomiting and defecation as part of a group therapy session organized by Otto Muehl whose own Sodoma Suite had been the conversation piece of the Quinzaine back in 1970.

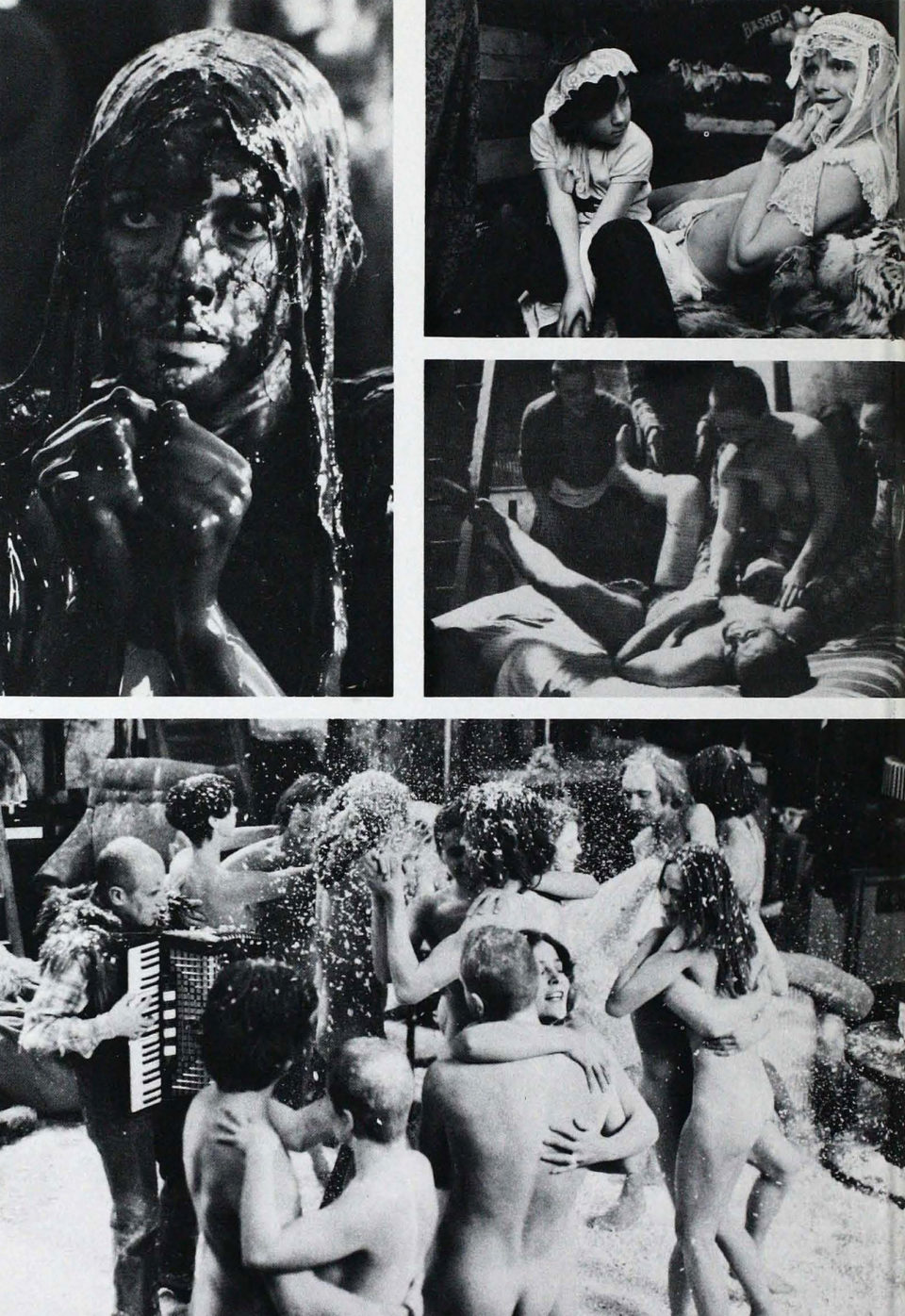

This was the first time that Makavejev worked outside his native Yugoslavia, with an international cast that included Carole Laure and John Vernon from Canada, and Pierre Clémenti and Sami Frey from France. Also intriguing was the fact that Ms. Laure had walked out in mid-production alleging that certain scenes were damaging to her dignity, both womanly and professional, a hazard that necessitated her replacement by a French-Polish stage actress named Anna Prucnal not to mention a revision of the original screenplay. On the screen, Sweet Movie unfolded in the fragmentary structure of previous Makavejev efforts such as Love Affair of a Switchboard Operator and WR: Mysteries of the Organism, with documentary interpolations breaking the original narrative at strategic points: a Nazi newsreel depicting the exhumation of a mass grave containing the elite of the Polish army is a factual footnote, and so is the sequence at the Otto Mühl commune although skillfully inserted in the development of the story. The two leading ladies appear in separate contexts, Laure as the definitive sex object defiled by men from Montreal to Paris; Prucnal as a socialist earth mother dispensing candy and death along the canals of Amsterdam. And there is the usual robust Makavejev humor: Laure and Sami Frey, who plays a charro pop-singer, become stuck in mid-fuck like dogs in heat and have to be disentangled by solicitous bystanders, among them a flock of nuns on a visit to the Eiffel Tower.

In Cannes at least, the one scene that really seemed to shock the audience was that of Prucnal, in the near nude, attempting to seduce a group of prepubescent children, a disturbing but valid metaphor. Even former Makavejev supporters were confused and disappointed by the film: to the Americans it may have seemed a belated, Mittel-European yippie yell. The French, as usual in such cases, came up with vague rhetorical reviews, but since the picture was being talked about it was decided to release it immediately. When it opened in Paris a few days later, filmgoers were treated to a process rarely seen on the screen since the early days of Fatima’s Belly Dance (and also used to mask nipples and pubic hair in Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie): black stripes, vertical or horizontal according to the case, covered the offending parts so that a visual pun on Goldfinger was totally lost along with many a plot point. There were cuts as well, but such was the censorship situation in France last May that audiences flocked to see the film at least during the first two weeks. Afterward, the attendance petered out and Sweet Movie closed.

The picture has yet to be released here, although Makavejev garnered some attention last summer as one of three directors to be invited to the First Telluride Film Festival in Colorado, along with Leni Riefenstahl and Francis Ford Coppola. In Berkeley, the film aroused vivid controversy; for American audiences, its interest obviously resides in its political rather than its erotic content. Not so for the French; and from the hindsight of April 1975, Sweet Movie suddenly seems to have arrived too early rather than too late. There are signs of détente in censorial matters since Michel Guy took over the post of Secretary of State for Cultural Affairs. In March of this year, political censorship was relaxed somewhat to allow the release of Stanley Kubrick’s 18-year-old Paths of Glory, a test case, for no ban really existed, only a conservative notion that the film offended national honor and dignity. Pornography is something else, yet hopeful distributors have optioned a number of American hard-core films, both straight and gay. Pink Narcissus, gay, soft- core, and four years old, opened last December to good reviews and attendance.

Makavejev’s own special brand of sexual reportage and political allegory would undoubtedly have benefited from the new policy. The director now lives in Paris and prefers to work outside his native land. His relations with Yugoslavian film officials are friendly, at least on the surface, but WR: Mysteries of the Organism remains banned back home. Despite the relative lack of success of Sweet Movie, there have been offers, the least likely being a John Milius script, Apocalypse Now!, which Coppola offered and which Makavejev turned down.

The following interview took place in Makavejev’s Montparnasse apartment last July.

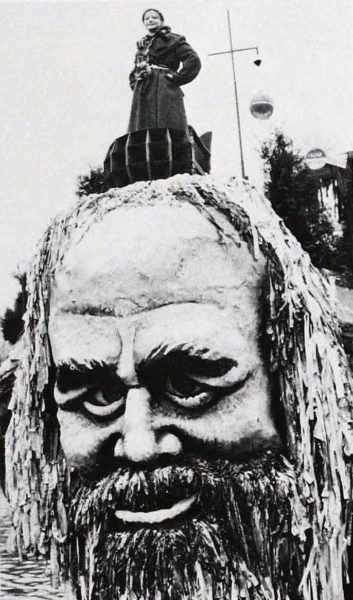

Sweet Movie: Anna Prucnal, captain of the Ship Survival.

Do you know the latest definition of hard-core pornography, by Justice William Rehnquist? “Representations or descriptions of ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, actual or simulated, [or] masturbation, excretory functions and lewd exhibitions of the genitals.”

What do they mean by “lewd”?

Well, they would be able to define it. But then, again, no two persons would agree as to whether a certain “exhibition” is or isn’t.

Well, I’m afraid this is not a very good time for critical filmmaking. It goes very much in cycles, and in general—not just in a particular country, though of course in very different keys-the present mood is oppressive and repressive.

Sweet Movie, though, gets away with the first cock on a French screen, perhaps because it’s a gallant quote fromGoldfinger—the “goldcock.”

Oh, I didn’t think of it that way. Anyway I didn’t worry about that; being satirical you’re always allowed to go a little further. I worried more about Pierre Clémenti, a well-known actor, performing in the nude. The “goldcock” is just an insert, a kind of comics-like joke. Clémenti instead is doing his own performance, his own contribution to the film, and we are recording, almost documentary-like, that performance. But what seems to have angered some people most are things that are not at all sexual. They have felt attacked for instance by the commune scenes. As soon as they see others playing with food, some people get petrified, much more than with sex, like Carole Laure putting Cachorro’s cock against her face and playing tenderly with it. Actually this is covered by a black stripe in the print now showing in Paris. As you know, Carole Laure objected to two tiny bits of the film and we had to remove them temporarily. As to this particular shot: she had seen the rushes back in November ’73, and only six months later she started legal action .

Perhaps she needed some time to think it over.

I suppose so. Actually this is not sex or depiction of sexual activity but a kind of very playful, childish, sensual contact, coming as it does after she has been nursed, breast-fed, all in the same vein. Only Cachorro’s self-castration “number” strikes a different note, being a parody of “macho” attitudes. But as soon as the commune starts playing about with food, and they start vomiting, pissing and all, people feel attacked. This is a kind of documentary about a therapy session, and people just won’t admit that into a fiction film. They feel attacked because we’re shifting the ground and they are not able to keep the compartments closed, uncommunicated. Stick to fiction, they say.

But you didn’t fake the pissing or shitting.

In action films where you have fight scenes, the actors or their stuntmen sometimes get carried away and really beat each other; sometimes it’s very difficult to draw the line between faking and real beating. There, of course, is the excuse that it’s the eternal moral struggle of good and evil. It is as if violence was OK as long as it’s not serving any kind of liberation. You’re supposed to accept things. You’re not supposed to throw out. You’re supposed to swallow everything that’s pushed down your throat. The real problem is what to do with biology in this context, what to do with this kind of new knowledge about where our problems are really located.

In Character Analysis,Wilhelm Reich states that our typical phases proceed according to a definite plan which is determined by the structure of each individual case. He lists: “loosening of the armor, breaking down the character armor which is definitive destruction of neurotic equilibrium, breaking through of deeply repressed and strongly attached material with the reactivation of infantile hysteria”-this is where Otto Muehl and your film come in—”working through of the liberated materials without resistance, chrystalization of the libido from pregenital fixations”—this is also in Sweet Movie—”reactivation of the infantile genital anxiety, appearance of orgasm anxiety and establishing of an orgastic policy…”

The interesting thing with Reich is that he never made any of his therapy public, never did any group therapy, always worked on a person-to-person basis, he hated homosexuality. So he had a number of his own hangups in spite of being such a great pioneer and breaking through much stronger than any other in his time or since. But this breakthrough led him directly to what people considered to be lunacy. He was so alone with his knowledge. His understanding of the connection between biological individual well-being and a political social behavior was so unacceptable that he was just left alone. He lived in a kind of ghetto, boycotted in a kind of invisible cage.

In his writings of the last period, before he was “railroaded” and put in jail, he discusses more and more this invisible enemy. He had this theory that “HIGS” were against his work, and “HIGS” were “Hoodlums in Government.” And the truth was that there were, of course, but he was always trying to define, to create new concepts to explain his predicament. He speaks of Moscow agents being sent from Washington; they were actually sanitary agents from the Food and Drug Administration, former Navy men mainly chasing people who were selling rotten food and dangerous cosmetics-you know, pretty tough guys. And they were happy to find this spectacular case of a crazy scientist up north in the Maine hills, who according to rumors had patients masturbate in strange coffin-like telephone booths. They thought they were going to find something sensational, and there were federal agents all over the states renting orgone accumulators, trying to get people to testify about the atrocious goings on at Reich’s.

Sweet Movie

In the documentary part about Reich at the beginning of WR: Mysteries of the Organism, all the people interviewed in the town near where he lived, look rather funny: small-town American-Gothic types. They remind one of those science-fiction Hollywood movies of the early Fifties, where there always were small communities endangered by giant ants, things from outer space, monsters from the black lagoon, what you will. And in that footage you got in Maine, a community was seen acting in the same way – only The Thing had been Reich.

What’s extraordinary is that these people in American towns in the Midwest live in a very good relation to nature—fishing, hunting, swimming. But in a social sense they are completely isolated in a kind of dreamland of permanent security. These little towns are the proletarian dream: these people have been poor, or their parents were, and came to America and found little plots of land and built Paradise there. Living always in this kind of permanent security, their own economy supporting them nicely, getting a fairly good education, feeling defended by government and army—anything from outside that doesn’t conform to their way of life is bound to be monstrous. This strange German scientist doing his experiments up in the hills was perfect for the part of Monster. They even invented that Reich was keeping children in cages for scientific purposes!

Like Jewish ritual murders, in the anti-semitic mythology. By the way, were any objections risen to the scene in Sweet Movie where Anne Prucnal seduces the children?

The French censors were very nice about it, they said they couldn’t deprive adult French moviegoers from seeing this kind of “research film.” They just had us put a warning in all the publicity, that some scenes may be provoking or hurting to many people’s feelings.

An Argentinian film censor was asked once why he didn’t allow on a cinema screen some footage that had been on TV screens. His answer was that even if more people, in figures, watched TV; they watched it in isolation, never more than four or five, while a cinema audience develops a group feeling, and if somebody booed or shouted at the screen others might follow and a riot could start. That’s a man who knows his job!

Somebody told me that the last military putsch in Brazil started as a right-wing reaction against some kind of left-wing unrest among navy cadets who had been watching Potemkin. It sounded so fantastic—Brazilian cadets only a few years ago watching Potemkin! We have here again the boomerang effect: positive action triggering negative reaction.

Top left: Carole Laure in the chocolate bath. Extreme top right : "Research film" in which Anna Prucnal seduces a quartet of prepubescent boys. Top right : Otto Muehl's "Primal Cream" therapy. Above: Post-therapy celebration in the Milky Way Commune.

Though WR is more developed and aggressive, of course, the basic approach of that film is much the same as in The Switchboard Operator, your second feature. Did it shock people in Yugoslavia back in ’67?

Switchboard Operator was widely accepted by critics and audiences. It became a box-office success and was part of a new trend in non-linear story-telling, mixing documentary and fiction all the way. Also in its fresh approach to subject matter: sex, everyday life, the relationship between work and love and History, and so on. The interesting thing in this experience is that if you have fiction alone, or documentary alone, the audience is geared to this particular genre or level of communication, but if inside a fictional story you insert documentary fragments they become more documentary than in a purely documentary film. Being geared to watch fiction you start discovering in documentary certain qualities that would have passed unnoticed otherwise, but you also start recognizing in fiction all this marginal documentary remains—the way people dress, move, eat, their homes. No matter how transposed on a fictional level, they keep a value as expression of a certain culture, of a given moment in history.

Anyway, I was happy to get many people to watch Switchboard Operator even without this intellectual frame of reference. I feel that all of us, those who started making films after 1960, were condemned to represent what’s called “author’s cinema”—-a kind of intellectual filmmaking. It’s difficult to liberate oneself from this, and try to be just entertaining. The great quality American movies had in their best days was to be made under market dictatorship. They were not afraid to please the market, and just had to be interesting all the time. If they felt like making some intellectual comment, they had to infiltrate it. Besides, ourselves being filmmakers from marginal countries as far as film industry go, we are supposed to express our national cultures. And being interesting becomes a kind of secondary duty.

Take westerns, for instance. Take horses, landscape, trains, guns. These are documentary items, and there is real action being done with them, in them, though the framework may be purely fictional. You get this strong impression of a life force at work, and bad guys against good guys become just a very simple excuse for a kind of biological display. Like the fantastic chases—real people, real horses, real rocks—this is behavior on an ecological level. It’s something we’ve come to reevaluate after these years of intellectual perversion in movies. Going back to roots. And the roots, of course, are in American movies, the only film industry in the world that is supported only by the public.

To read the full interview, purchase a copy of the May/June 1975 issue.