Interview: Bruce Baillie

Also-rans on the screen were some products of bouncing Bolexes and several passionate personal statements whose message was apparently too ineffable to be expressed with technical competence or logical sequence. Immaturity and disorganized psyches were projected in several films screened. A synopsis of one of these (or, for that matter, all of them) is approximately as follows:

The filmmaker, who is making a trek from here to “there” (unspecified place or undefined state of mind) attempts to represent a chaotic state of affairs (personal, political, and / or social) by showing chaos on the screen. The result is a compilation film pieced together from scraps of footage shot during the filmmaker’s pilgrimage (via motorcycle, Volkswagen, station wagon, etc.) across the American landscape.

Interspersed are fragments of TV commercials, shots of cars driving at night, filling stations, people lighting cigarettes, “earth” shots (parched or fertile, possibly switching from black and white to color), sunrises, clouds and more clouds, animal close~ups with emphasis on the eye, roadside signs reading “Jesus Saves,” fast cuts of highways (we’re covering a lot of territory, you see), traffic jams …

These are the ingredients. Mix in any proportion and almost any order, and serve on at least one screen.

The super-category of expressional filmmakers cannot make do with but a single image at a time. Their scenes are double-printed to suggest either ambivalence or duality, and they intersperse black (or white) frames to indicate profundity. For example, superimpose pig heads over Rotary luncheon (pigs are hungry, men are hungry, hence men are pigs).

What you don’t catch on film, put in the sound track: carnival music, construction sounds (especially grinding, burping, groaning noises), rushing water, and heavy breathing, as in passion or emphysema. Play lonesome jazz over a bum’s face and cut on a blue note. Follow with either a cop or the American flag, and switch music to jelly-roll jazz. Print Negroes in negative, turning black into white, thus solving the race problem. –Harvey V. Fondiller, from “The Flaherty Film Seminar” Popular Photography, December, 1969

This interview was recorded at the 1969 Flaherty Seminar and edited by the filmmaker

Quick Billy (Bruce Baillie, 1971) Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives

I had a question about Quixote, which was, it seemed to me, really two films—a film with two sensibilities—one about the West and one more directly about politics, Vietnam, the urban set-up. There seems a very clear demarcation point and I thought both would have made supremely satisfactory films. I just wondered why you put them together. Personally, I felt that for me, as an audience, it might have been more satisfactory as two separate films, dealing with separate things…. I don’t see that it’s two films. How do you separate the land from the politics, the land from the life? I see it as a whole collage of America, with an inner kind of way of thinking, and the impact doesn’t hit me intellectually, it hits me somewhere where I hurt, I just wanted to cry somehow after the film.

I suppose one of the reasons I came here was to see the film. I liked seeing it, but it’s awkward for me in places, seeing it as an audience. The techniques were the best I could do with what I knew, how I could work, and the money I had. But it was more just really what I could do. I couldn’t have done more.

Specifically, the multiple imagery technique was the taping of original A-B-C rolls over a light box with opaque mylar, so that things were kind of coming and going like screens moving across each other. It was really crude; this was one of my first films where I wanted to share the frame, one diverse material with another, without the effect of superimposition.

Most of my revisions were clarifications (1967), just taking out a lot of things, taking away things so that you could see the essential images more clearly. Still there is unclarity and no real control in some areas. To really reach into a frame, the frame, and pursue the logic within the frame and without, according to sequence, etc…. When you get into more abstract work, for example… I’m thinking now about watching it as a storyteller like Gorky… in watching my frame, whether it’s abstract or not, I want to guide the relationship toward some climax, resolution—as in the narrative, each phrase and the phrases in relationship to one another toward the whole.

How do you work? Do you shoot with an idea in mind, assemble some stock footage that fits into your mental framework, and then begin refining it down, or do you have a plan to begin with, or what?

A: It’s like a quest, as I suggested. When I think back, I refer to a man from the past. This was a hero-maker, a storyteller, an image-maker with whom I gradually became concerned generally. But I was concerned with heroes—a hero concerned with heroes. Like the poet-warrior he would start when it was time to start, knowing really not particularly where, and then where he came to, the places he came to, began to tell him where he was going, and then he, of course, began to know where he was at. It wasn’t the Don Quixote of Cervantes I set out to discover, or re-discover, it was only an adventure, I don’t know why he came to me. To that time I hadn’t read the work.

I began to keep notes as I went—with Lilian, Dog and Volkswagen—through the Southwest, back to California, borrowing a little more money from a friend in South Dakota, going on over the Sierras toward Idaho and Montana into winter. For whatever reason I also began the daily reading of Don Quixote. As this form became known to me it was both a shape and a vehicle for my film—my adventure—and that peculiar burden of a thing coming into being.

I can see a great collection of fantastic images working against each other and I can’t see how you put them together in that shape. That, to me, is what I try and find in anyone’s work, how they put them together, and I couldn’t grab it… and I was wondering is it something to be taken as a whole, or is there a linear path to it that I just missed?

Doesn’t the linear path make the whole?

Yes, you get bombarded. It is a total experience. You can’t wend your way through it, it just happens. Maybe it’s all around me, maybe I can assemble it that way at my own time rather than the time necessary on the screen.

That would be nice like a newspaper, invent your own news.

Because the form is linear and that’s the way it collected, I couldn’t get with your work. I couldn’t get your linear form.

I’d say that it probably had a pretty formal, linear structure. During that period of time I came under the influence of a number of teachers: Bach, Brakhage, Cage, cummings, Cervantes. Anyway, I remember myself having a very acute and long-winded joy with this film and its structural problems. I loved them. Like Cocteau, obsessively structuring the silverware between the designs on the tablecloth and the plates. Like the Cervantes novel itself, filled with chapters, dialogues, songs. Some parts discreet, others continuing, in varied form, into new sections. In e. e. cummings: “Uncle,” the last word of a stanza; his proper name beginning the next stanza—a full double space between stanzas.

You being in closer than I would be, your fragments are more fragmented and it’s hard for me to do all those extra steps and put it together so I can grab it somehow.

Every time there was a cut, or joint, section succeeded by section, frame by frame, it was carefully, “heavily” conceived. If it is a work of art—a living thing—it might take some acquaintance with it over a period of time.

It is a little like running and just missing a train that I wanted to catch.

My own technical criticism of the film, again, is that there was lacking, especially in those complex simultaneous parts, the depth of control that I… seek. I have never seen it in a film yet.

You can see it on another level, perhaps, in brilliant works of narrative cinema. But, in an essentially non-storytelling film, there are at some points quite different problems, for example, in this pursuit of the reason for/within a film phrase—for the relationships (”that go down”) from phrase to phrase and within the frame itself.

I had a thought while I was sitting in the theater, between several films, about how different the moments are when one thing becomes another in succession. The cut—really the heart of the filmmaker’s work—and the moment. He makes the moment by cutting. I believe that with certain cuts it is impossible to find the “right” exact moment. On each viewing, with each viewer it will be a little this side or that, having “in each case” a different meaning—a different relationship to the “center” or moment. There’s some kind of cut—I’ve never noticed this before—that will never be solved. That may be good information.

What do you mean by “solve”… That cuts will never be solved?

Well, cuts are problems to a man that’s making them.

Do you mean solve in the sense of where it should be?

Yes, for each time, in any kind of film—the most simple, descriptive kind of film—there’s an exact moment for each cut, which a master finds and makes. But as I said, it seems there are some cuts which will always occur a little differently to the sense, to everybody, to the theater itself. There is no universal place for some cuts, I guess.

I was particularly taken by the sound. Did you have that growing with you in the car too, or did this come later?

I was recording the pieces in the same way I recorded the pieces of the visual. When I came in from the road, after three quarters of a year, I had notes that covered perhaps a fourth of the sound. Otherwise, there was only a vague idea of it at that stage.

When miraculously I had found the money to develop and workprint all the film I had mailed home during those months, I began to put the film together—a film made of many distinct parts, not unlike the novel. It began in mid-context with the old man, Archie Jewell Cradick of Deming, New Mexico. A definite structural idea, based on the peculiar length of the film—I wanted the man to be talking right into the screen, in mid-context, without any fade, without easing in.

Edited to the picture for the most part, I would note down sound relationships as I went… also playing stretches of sound with the picture as I edited. Finally, the sound track came as a last phase of work—in the way of filmmaking it was in part a separate endeavor. This particular track almost plays by itself. It might be nice if on radio they occasionally played the tracks to some of these films.

Some of the basic sound material is from compositions and other tapes of Ramon Sender, The San Francisco Tape Music Center. They were isolated, re-worked, etc.—combined with things from the road, and so on. Another sound base was from Charles Ives’ symphonic work dedicated to America, since I discovered I was making a film that seemed to me very similar to his symphony, filled with Protestant hymns.

Since I know that every film you make, you make several hundred decisions every ten minutes in the process of shooting and editing, it has always seemed to me that it would be pretty difficult for every filmmaker to remember every reason why he made every decision, and that fact that you can’t leads me to believe that you are giving me a better impression of what it’s like at least to make your kind of film than you might if you could remember each one of those thousands of particulars in them. At any rate, regardless of how you explain them, they are quite an accomplishment. I wish you’d talk a little bit about Valentin. It seems to me a simpler image.

Sometimes I wish Valentin would move a little bit slower, about another half pace slower. It’s odd, I suppose I didn’t really know when I was so close to my subject that he would move a little bit faster through my screen. That film came out of the painful experience of one making a record of his own life. I remember that the strength of my impressions daily there was so severe that I really thought I couldn’t live through it. It was being a foreigner, being an outsider by choice; even the horse rejected me down there, I couldn’t take his picture. It, being the last film I’ve made, led me or at least indicates where I feel I’m being led, and that is into an essential question about recording. Whether it’s a distinct action from those actions you make according to just being, and not being a recorder of being, or the concern with creating another being. That is, I am talking about being an artist, a vehicle through which something flows and is one thing and then another; or I don’t know that, but at least it flows through and all the particular pain from that flow was really at a peak when I was in Mexico. I still saw myself as a recorder, so I sought to make a thing from being in this extreme environment and finally, after a number of months in the same town, behaving myself, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I saw a girl on a horse and I looked all up and down the street for her, risking hanging, and finally found her aunt’s house. I mean I felt that there in that environment—you probably have some feelings for her from being there and seeing the film—that public execution was a risk that I was running by asking. But I asked her and then I had a meeting coming up with her father, Manuel. I was afraid and it was about three days to go when I was going to meet him on a corner at night. I had never seen him and I wasn’t going and a little boy came to the house and said he was waiting. So I went to see him and I just said the thing that I had said many times, just learned to say, that I made movies and there would be an exchange of money to the family because they were poor, for my being able to be part of their family, allowed into their house at least. They lived behind a wall with the horse. I wanted to sleep at night on the girls’ floor and photograph them through the cracks as they woke up. I never got that far but that’s how I felt. I was completely, erotically, totally, taken with Mexico and there was no way out. I had found that to make films was the way out. Now I’m looking for how to stay there always. I haven’t found how to do this yet. Neither in or out, but just there, something like that. Instead of making the transit, making way, instead of depending upon a vehicle, instead of having a weapon at my command, a thing between, instead of thing-making to get there. So, in Mexico I began to shoot, using an extension tube with my Bolex and the three-inch lens, skin, the vibrations in the wooden blocks, and the ground, and the sun coming up through the blocks, and the blood flowing down there in the earth. And the sun was so intense I would have thought that the images would be more light. They were so heavy. But then I deliberately bought Kodachrome down there and kept it pretty low. Like I say, I wish it were a little slower, absolutely all of it, by a fourth. The game, loteria, the girls were playing—we used to play with the girls every night on the street corner—the game is the kind of game that’s like a whole family, where playing lottery at night is a kind of nightly reassurance of the whole story of being alive, with all the animals, the sun, the elements, all on the cards. We’d play it every night.

Well, anyway, so that game was in the middle. The sync part was kind of astonishing to me technically, since I was jaundiced at the time and probably shouldn’t have been working. That’s all I had to do was that sync passage, maybe a minute and a half, and there were two passages within it. I didn’t have a sync outfit down there. In fact, I had to borrow a very bad tape recorder.

Is Valentin your favorite of all the films you’ve made so far?

Well, I kind of liked it. I named my horse after that film. I’m still stuck with a kind of primitive view of my existence—like horse, home, woman, man.

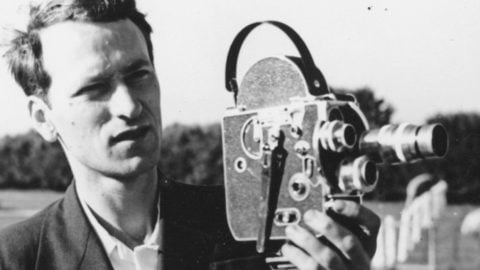

Portrait of Bruce Baillie. Courtesy of BAM/PFA.

In Castro Street and Mass I thought I saw a style beginning to evolve, and now, for me, you kind of break that style with this one, and I am wondering if it couldn’t possibly be the rejection you felt that could have resulted in that kind of style in Mexico?

I knew pretty clearly when I set out shooting where my style was, and probably if I could really remember, could bring up why. It would take me a while to remember though. In all this stuff while we’re talking-I don’t know how the talk’s gone so far—this is good enough—very personal, it’s fun and nobody that really knows not very much should get to talk a lot, I figure. So, if it doesn’t come across in the sense that we’re all connected, that we’re all from the same family, then it’s sort of worthless. For example, what we call and still think of an artist, the question why he might have come on to a different style might be pretty revealing about a lot of things. I can’t remember though. Maybe it’ll come up.

You said you were having sort of an erotic affair with Mexico and then you said that you wanted the time to be slower, which reminds me that we unfortunately saw Valentin at the wrong speed here and lost all the sensual qualities of it, and I’m thinking that maybe, in a way, if it had been slower it would have expressed the sensuality of the air, erotic things that you felt.

Well, that film was finished and as a finished living film, I can’t really question it myself, that’s the way it is. It’s like looking at a friend and wishing he would slow down.

I was very held by what I felt was the struggle in the film between, say, the Indian life, which was in a way the content and which was very pure and simple, and on the other hand something that was a kind of abstraction and a kind of chaos which came in the form. And I wonder if you’re conscious of that and if you feel that as you get closer to that Indian kind of life you’re going to get some of that slowness that you felt the lack of.

That’s a good question. I think I wondered about that once. That’s just a good question to pose. It doesn’t need an answer. A very good one. It’s for me a good question anyway. (Silence) Well, what would you like to hear? (Laughter) I mean, kind of generally.

I’d like to hear how conscious you were of that struggle.

Probably absolutely unconscious of it as an aesthetic problem, and probably just now noticing it. It may be that its pace is, you might say, correct or real or truthful to what its aspirations are, where it’s going-thinking of it like a brother or a friend. I can’t tell.

It’s a combination of elements which stop and begin with the cuts, which somehow seem to have an inner logic and a kind of inevitable quality that Quixote built very strongly, in the way you shift from one block or section to another. The connections are always clearly stopped and then started. It’s hard to say quite why, but sometimes it’s enough to say that it works. It’s its own justification.

In Valentin there are several heartbreaking images, primarily of the people, and I wonder how you go about finding these people. I mean you explained how you found them, but…

I will answer according to my past work. I always entered my work religiously, and always when you’re devoted things come your way. They make their own way, they find their own place. If you commit yourself to it you’re bound to pass through. Before you start, of course, there’s no way to anticipate and that’s why we have such an old fear in us about walking, about commitment or taking roads, since they are unknown. I suppose that’s why we have discussions, in fact.

The Eskimoes, as I understand, when they make a carving, they pick up a rock and they see what’s inside the rock, the carving that’s there, and they just try to uncover it.

Well, let me tell you about Yum Yum.

They all arrived on Saturday morning to kill Yum Yum. “As a trained reporter,” the first thing I did was to go back to where Yum Yum was while they were preparing the garage. All the tools and knives were sharpened and laid out, and I saw who was to be killed that morning and recorded it properly, maybe three shots, I’m sure. When he got up from where he was lying, I kind of stood behind a tree as though I’d just got there. That was his first perception, recognition? … isn’t that the first time? … he knew this was going to be some kind of fun Saturday morning. And I began to look at him myself, and I was looking at him, and this was a new question in my life that I came to. The next step was when all the boys prepared the tools. And then I took pictures of the boys in their anticipation. They had a gallery in the garage up in the hay. I wrote down some of the things they said so I wouldn’t forget, since I was recording. I wrote down, “Save my place,” and “You got the gun?” I saw all these elements and photographed them, each separately. Then one of the oldest boys went to get Yum Yum. He didn’t want to come out of the yard, and then there was joking by the father, saying, “Oh, come on Yum Yum, you never did like me,” and the boys bringing him along with some Olmalene. Now Olmalene is the most wonderful food for a cow or horse. It’s corn mash, barley, oats and molasses. There isn’t anything more wonderful. He had some in the bottom of a pail but Yum Yum wasn’t too interested—he was scared. Then he came out and was shot in the head. Well, the shot wasn’t too well placed so Yum Yum had a lot of blood pumping out of his head and I was photographing it. Okay, we eat cows every day and I had to do that job or not do it, one or the other. He walked around half-dazed with a huge bullet in his brain, wondering how soon it would be before he was dead.

These are good men, the men who were killing him, and the man with the gun in his hand was nervous, though he was an extra-good man. Then they had a dead shell and I was setting up with my shutter speed at 1000 and all. Everything was set right, waiting for a second shot so I cou Id get the shutter the moment the shot entered the animal, so I did. The boys were all astounded and watching, so I shot them kind of like you see in the newspaper. This, and then the reaction to this: coverage, it is called. So, I did a good job and bought beer for everybody while Yum Yum was being made into meat. It took him a long time to die. And then I spent the day looking for girls, I think. In the evening, I was riding down Main Street in my truck and all of a sudden I felt nausea. It wasn’t the fact that the animal was killed, or anything, it was just that I had another huge question now. What kind of work was I doing there, which meant to say, “Who are you? What part did you have in his vision, this animal to be killed?” And I know better than to be completely overcome by sentimentality. I can tell myself that we all die and the animals crushed on the highway or made into meat are just making a transit… It’s important, nevertheless, the man, the participant, that journalist in the front row at the gas chamber, know his relationship to Death as well as to Life. Also, it may be that my whole feeling was only for Yum Yum.

Do you know your relationship to it [Death-Life]?

No. Being nothing like my heroes, I haven’t worked on it, I’ve let it go. Of course, I can also give you some more information—some people know about this, and some not. I know a little more lately. These kinds of unknown deeds collect in each of us. They have a particular form-this has the particular form of the butchering of a steer. And if they go unattended, they reoccur in that form, in that unknown form, and the most convenient form for those unknown specters is terror. That’s where fear of the dark, fear of an open door, fear of those “visitations” that each of us gets occasionally, come from. Each of us gets occasional indications from some unknown presence that would have himself invited, and we usually say, “No, no, no, no, no” even among the best of us, and the reason we say no is because we invented those presences (in fearful form) nurtured by our own neglect, I think. They needn’t be terrifying; they can be peaceful and wondrous.

In Mexico they have the fear…

Well, Mexico works it out a lot better than we do. Their masks, their parades…

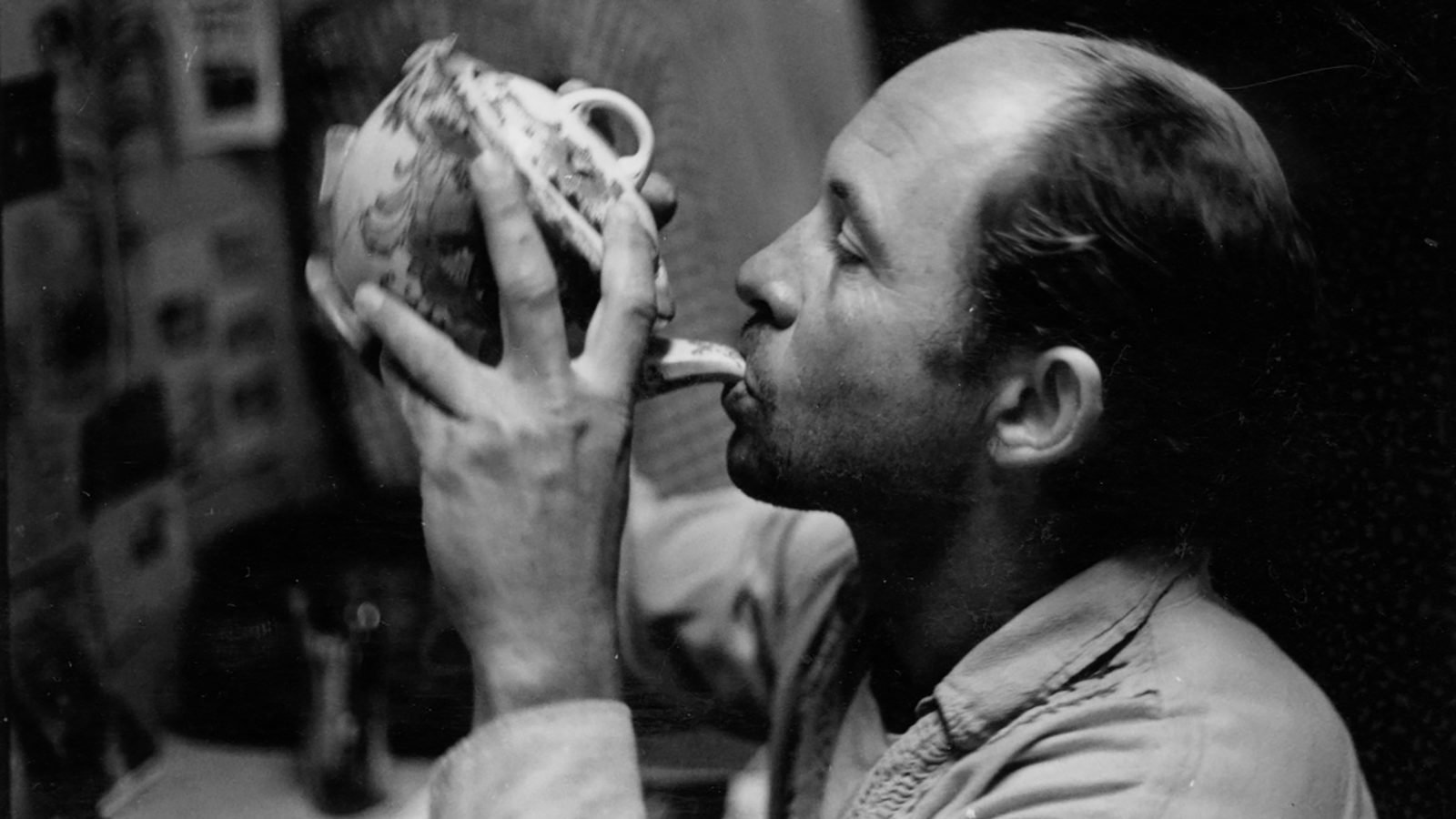

Castro Street (Bruce Baillie, 1966)

I’ve been thinking about two things the whole afternoon. One is that it is like Dostoevski saying that the man is always better than the work, and the other thing I’ve been thinking about is that if you actually became an Indian, lived there, became like an Indian, there’d be something in you that would still have to make film.

I don’t know.

Do you think there is a doubt? Is film a way into life, and if the life if full, is filmmaking so important? If the life is realized, the art falls away?

Maybe you’d just like to weave or take care of horses if you’re “retiring.”

I wonder about adding to the noise men make? Well, it isn’t that it’s a distinguishable question—initially it’s not a discrete question between for whom, since the man doing the making is partly the man doing the receiving, the using. And then it’s not different again since to decide about it or, for example, to go on the wrong road, to continue on the wrong way, he’d be a wrong-way filmmaker. He would do nothing, his films would be noise, so that’s the question…

What would make you feel that it is the wrong way?

I don’t feel that necessarily. I’m just questioning the road, the way, the way of making, of doing, of committing energy outwardly into shapes and forms and things.

Is it somehow because the return isn’t what you hoped it might be?

What return could there be, I don’t know. I can’t imagine any.

Do you feel that your films are accomplishing something of what you put into them?

Well, I wouldn’t know that… I think probably some of those things do matter but I don’t know which, and I don’t know how.

Does it matter whether you pick up a camera or whether you dig a hole in the ground?

There have been some successful human artists, human beings that could function singly and were brilliant thing-makers. Well, there’s a tradition that says that man, the artist, it’s all right, he’s a madman! It’s a glorification, a heroic, a romantic tradition, and it’s one which will no longer serve. Making a passage right now, we’re in a changing no-place, a gigantic uncertainty; a man who might choose to foolishly accept that tradition becomes very mad in the twentieth century, really. It was still useful in Europe right through Genet. So, now demands something unfamiliar, demands another norm, the shapes we used before don’t work now. Hardly any you can name—even the size of shoes—everything has disappeared, and its usefulness. It’s terrifying and a man who wants to enter that kind of life with a tradition saying it’s okay to be mad as long as you’re a filmmaker! I think it is Life magazine’s job to list those certain principles that have worked for centuries. For all I know, Life is handling that already, I hope so. We should learn in the third grade about romance, life and death, etc.

Then you are questioning…

I’m questioning the romance that a man can be two things, that he can be on the one hand this, and on the other that, which offers him madness. Before, some men were strong enough to contain it, and in fact have been brilliant creative madmen.

What do you do when you’re driving around in your Volkswagen and you get lost…

I call Life magazine. (Laughter) I do.

What do you do when you get lost when you’re in the desert or in Mexico or something? Do you just keep on driving, or do you stop and go back, or some people stop and ask, or do you open a map, or do you just go by your feelings towards east or west in the general direction? People have different ways of doing things when they get lost—the reason I asked that is you talked about going in the wrong way. You can go in the wrong way and when you make a mistake, the only way to correct a mistake is to stop doing it. You can go back and take the other fork, or something, but maybe you don’t. I’m just asking what you did in your Volkswagen.

That’s something I think people really have to work on now—to know if they are on the right way or on the wrong.

I overshot this place by twenty-five miles the first day here. I had to drive all the way back. Well, you’re obviously considering retiring, and so forth, or continuing making films, and you say that might be the wrong way.

I think that’s probably the story of most people’s lives, perhaps, being in the wrong place in the wrong time.

The problem seems to be to make that step into the dark, not knowing which way you are going to go and allowing yourself the freedom, trusting that you have to go whichever way you feel. I don’t see how you know—I think you can know when you’re mad. And whether you can stop that and still be an artist, if that’s the way you would go—

I think the trap that awaits man is his attraction to movement. As you go along the way, you gradually become familiar, and as you become familiar, you become gradually possessed, just like in the way of families, attached to it. Now, my new mystery? Each time is new, brand new, no rules for it at all except for the footwork. My question is can I do that work and remain unattached to the environment passing through that world in which I will inevitably find myself. All adventures seem for us to have a way in and a way out?

In the beginning, if we’re well acquainted with it, we don’t look for it again-we don’t even want it—and initially, early in the adventure, we find ourselves free. It’s a romance, we’re in love again! We’re free. Because that’s what romance does, temporarily, free us—and gradually we become wed to this new familiarity, this new world, and I want to know about that. I don’t want to get there ever again. I want to stay in transit. Not lost like a ghost. Ghosts are those who have lived, who have had form, who are familiar with having a place, being somewhere, and have turned off, deceased in any sense you like, and are constantly terrorized by all the unresolved stuff of their lives, the result of their living. There’s more about ghosts that I don’t know at the moment.

But I don’t mean like a lost soul. I mean the contrary, like a permanent infinite kind, always here, just here. No matter where.

So, I am questioning the vehicle, art. I am wondering about it. I wanted to be an artist all my life, since I was a little kid. Late in my life I finally found tools and worked hard at it making films that I loved. They are all off now on their own—they are whatever they are, and I wonder now-I have much more skill now at my command at this moment than I had a year, two, three years ago-and I wonder at the film I’m making, and may not make. So, I’m asking can we make that new adventure each time, can we make it now and take our tools with us from here to there, can we carry these tools, can we use them? What can we possibly know about bringing anything to a strange environment? Now, I can answer a little bit just for myself, as having been a film artist. I always felt that I brought as much truth out of the environment as I could, but I’m tired of coming out of. It’s like being comfortable. (Like the author of Don Juan)—like you go on an adventure but no matter what you do, or where you go, you know you’ve got Berkeley back there, or whatever safe place it is. It’s home. No matter how fierce the Revolutionaries, they’ve all had a home.

But I want everybody really lost, and I want us all to be at home there. Something like that. Actually I am not interested in that, but I mean that’s what you could do. Lots of people would like it. I have to say finally what I am interested in, like Socrates: peace… rest… nothing…

No movement at all?

Nothing. Okay, that’s enough.

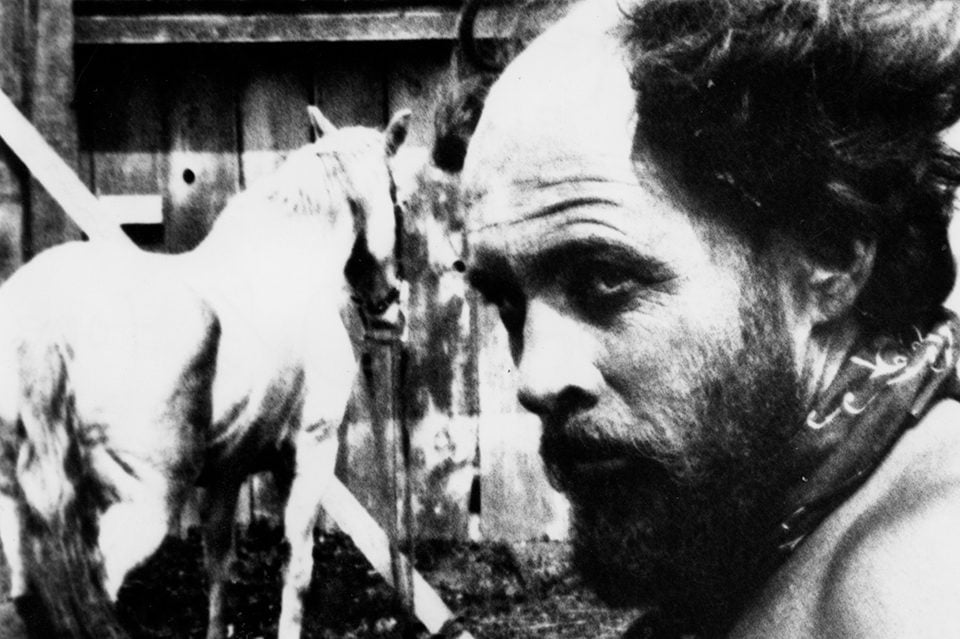

Mass for the Dakota Sioux (Bruce Baillie, 1964). Courtesy of BAM/PFA.

FILMOGRAPHY: BRUCE BAILLIE

(notes by Bruce Baillie)

1961

On Sundays

35 minutes, black and white.

With Miss Wong. Document of a lovely friend and of San Francisco woven together in fictional form .

1962

David Lynn’s Sculpture

3 minutes, black and white.

Shown in our early Canyon Cinema showings, never printed. Example of “The News,” an inexpensive local means of combining film seeing and filmmaking.

Mr. Hayashi

3 minutes, black and white.

Short document of a man, made originally as a “News,” and now in distribution. Midwest Film Festival Award, Ann Arbor, 1963.

Friend Fleeing

3 minutes, black and white.

Another “News,” made for my friends and not printed.

The Gymnasts

8 minutes, black and white.

Semi-narrative, partly documentary, my first film with “fancy” editing. Originally a “News,” now in release.

Everyman

6 minutes, black and white.

The sailing of the boat Everyman into the Pacific nuclear testing area as protest. John Adams and guitar.

News #3

3 minutes, black and white.

Material from a Cuban rally intercut with peculiar rock formations from my California travels. The sound is radio music and mob sounds.

Have You Thought of Talking to the Director?

14 minutes, black and white.

Made while under the first impression of Mendocino, up the coast north of San Francisco, and of my friend, Paul Tulley. My first “serious” piece.

Here I Am

10 minutes, black and white.

A film for the East Bay Activity Center in Oakland, a school for mentally disturbed children.

1963

To Parsifal

16 minutes, color.

Still one of my best. A tribute to the hero, Parsifal. The first part is offthe California coast, at sea; the second part is the mountains and the great slow freight trains through the passes. First Award, San Francisco, 1963.

1964

A Hurrah for Soldiers

4 minutes, color.

Dedicated to Albert Verbrugghe, a Belgian whose wife was killed by UN soldiers in Katanga, December 1962. A collage mishmash with a strong recognition within it of the quality and historical place of the soldier.

The Brookfield Recreation Center

6 minutes, black and white.

Made for the Oakland Public Schools on an experimental series of classes in the arts.

Mass

20 minutes, black and white.

A film mass, for the Dakota Sioux. Grand Prize, Ann Arbor, 1964; Moholy-Nagy Award, Illinois Institute of Technology.

1965

Quixote. (Revisions 1967)

45 minutes, black and white and color.

Originally intended for two simultaneous screens. “A view of America and Americans, sometimes complimentary, often embarrassing, always fascinating…. The sound track is a montage of the sounds which surround us in modern life.” -Gregg Barrios.

1966

Yellow Horse

9 minutes, color.

A cycle scrambles poem. Shot while editing Quixote. Bass solo by Pat Smith, a Los Angeles musician friend .

Tung

5 minutes, black and white and color. Silent.

Portrait of Tung: “Seeing | her bright shadow | I thought | she was someone | I | you | we | had known.” Numerous first awards; Ann Arbor Touring Festival, 1966.

Castro Street

10 minutes, black and white and color.

(“The Coming of Consciousness.”) Conceived in the form of the street itself, Castro Street in Richmond, California. A Standard Oil Company refinery on one side of the street, railroad switch yards on the other. Male and female counter-motion. Ann Arbor Touring Festival, 1967.

All My Life

3 minutes, color.

“Singing fence,” Caspar, California.One continuous moving shot. Ella Fitzgerald singing “All My Life” on the soundtrack.

Still Life

2 minutes, color.

From the commune life at Morning Star, where I made Castro Street.

Termination

6 minutes, black and white.

Tulley and I made this film for some people up at the Laytonville Rancheria. They were being “terminated” under a new Bureau of Indian Affairs program.

Port Chicago Vigil

9 minutes, black and white.

Kind of a “News,” for the people of the 24-hour a day vigil around the US Marine Ammunition Depot at Port Chicago, California.

Show Leader

1 minute, black and white.

A repeated shot of me in a stream talking to the audience, used as an introduction to Baillie film programs. Rent-free.

1967

Valentin de las Sierras

10 minutes, color.

Made in Chapala, Jalisco, Mexico. Titles in Spanish. Song by Jose Santollo Nasido en Santa Crus de la Soledad, blind singer. First Award, San Francisco, 1968.

1967-1970

Quick Billy

60 minutes, in four reels. Plus Rolls #41,42,46,47; three minutes each. Color and black and white.

The essential experience of transformation, between Life and Death, death and birth, or rebirth. The first three reels, which are color and abstract; structure adapted from the Bardo Thodol, The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The fourth reel, in black and white, is in the form of a one-reel Western, summarizing in drama the material of the first three. “The rolls” are silent rolls of film that came after the film itself, like artifacts from the descending layers of an archeological dig. Aesthetically complete, they are part of the total work. (Rent-free option.) Part IV was a group effort by Paul Tulley, Charlotte Todd and myself.

Distributors:

Audio / Brandon, 34 McQuestern Parkway, Mount Vernon NY 10550.

Audio Film Center, 406 Clement Street, San Francisco CA 94118.

Canyon Cinema Co-op, room 220, Industrial Center Building, Sausalito CA 94965.

Center Cinema Co-op, Columbia College, 540 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago IL 60611 .

Filmmakers Co-op, 175 Lexington Avenue, New York NY 10016.

Also co-ops in Tokyo, Stockholm and London.