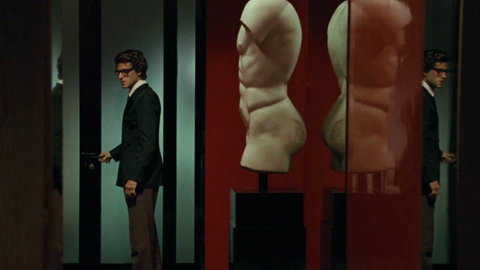

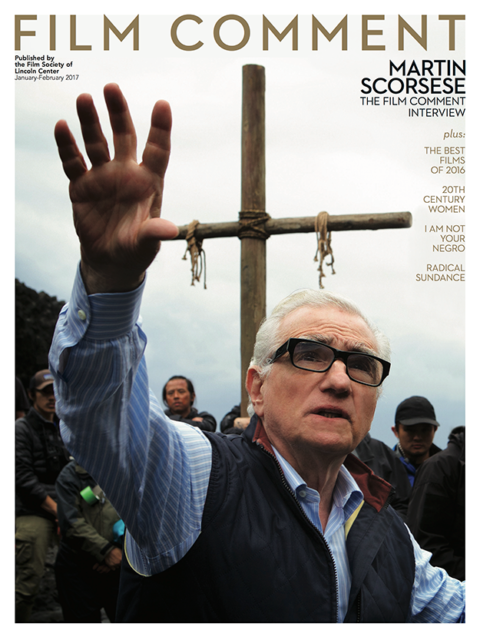

Directions: Bertrand Bonello

Nocturama, the new film from director Bertrand Bonello (Saint Laurent, House of Tolerance), ranked third on our Best Undistributed Films of 2016. It opened last summer in France, but no U.S. distributor has been announced yet. Film Comment spoke with Bonello last September soon after the film’s international premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. The following is an unabridged version of the Directions interview in the January/February 2017 print edition.

Nocturama tracks a band of young men and women as they commit acts of violence in Paris and then hide out overnight in a mall. Given France’s recent experiences with terrorism, did you have problems shooting any of the material?

No, not at all, in fact we shot [in 2015] before the November attacks and after the January attacks. For example, we were even allowed to shoot a real car that blows up in the middle of the city. People are very sensitive and fragile, of course, but I think everybody understood that the film has nothing to do with what we lived through. The reasons are different, the targets are different; it’s not about ISIS. I think it’s a little more difficult for people who haven’t seen the film, because there are some ideas of what the film is. But when people saw the film they put it back in its right place. We are a little bit on our tiptoes when promoting the picture. It’s a film that really needs to be followed up with.

The second half of the film, in the mall, is like a remake of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. But there’s also a John Carpenter and Alan Clarke influence, too.

You quoted the three filmmakers that influenced me the most. Two days before shooting, I rented a theater and showed the actors and the crew Alan Clarke’s Elephant. It was great because when they came out of the theater they were in a totally different mood and they were in the perfect mood to start shooting.

Talking about structure, there is a lot of overlap in perspectives. What prompted that?

It was always coming from problems: geography problems, time problems, how to work simultaneously. I have a lot of characters and in the mall story there are eight floors, so you try to find ways not to get lost. You have three relationships with time: at first with precision and simultaneity; in the second part of the film, time stops and it becomes about finding a kind of tension in the moment; in the third part, it all gets mixed together. This is basically how I constructed the film.

As you said, your characters aren’t ISIS terrorists, they are trying to be anti-capitalist. But they are totally consumed by this millennial consumerist culture: mainstream rap, fashion, etc.

It’s not a 1972 movie, in which the first half of the film could be like a perfect [theoretical] program. Today’s world is much more complex and full of ambiguity. It can produce terrorism and capitalism at the same time. I wanted the film to express this ambiguity. They’re young and they’re a little lost in the head. It’s not so clear and not so easy. I wanted the film to reflect that.

It’s not entirely clear, but you have a vague idea what they’re protesting against. Why did you choose to make that ambiguous?

I was afraid the discourse [on what they were protesting] would create a distance from the action and I didn’t want that. I wanted the discourse to be within the action. A lot happens over the course of 20 hours. You could have a prequel of the film, a few sequences that say, ok, we could do this, do this, do this. Then you see that. You have a distance. Here you have to dive into the action at the same time you’re not allowed to have that distance of detachment.

So, again, the Elephant influence.

Yes, in the Alan Clarke, there is hardly one word in the film, only action. And at the end of the 40 minutes, you understand exactly what a civil war is. It’s someone walking across the street and killing someone. I think it’s great when you can have the political sense of something just through the action and not through the words. That’s what I was trying to find.

All of your films have great soundtracks. This one was especially good. Can you talk about getting the music together for the film?

It’s something I try to work on very early, in the first draft of the script. So I decided to have some original score in the first part. I was trying to find the best textures. The thing that was most difficult was to find the sub-bass stuff. It’s not composition, it’s just working on textures.

I wanted the store to be a kind of jukebox for the characters. Of course, I chose the pop songs myself. Each time, I was trying to find the best song to express the feeling and the sensation that I wanted at that moment. It becomes like a scene with dialogue. It means something. For example, with Willow Smith’s “Whip My Hair,” I was trying to find a very sugary pop song to go against the images of explosions on the TVs to create something quite violent with a song which is not violent at all.

Rhythmically it is violent.

Yes, but it’s meant for dancing to and being happy, and it’s a song by a 10-year-old kid. But then you put this song with these images and it means something else.

That’s why I ask. I think that’s such an excellent choice because they are watching these explosions that they made and saying, “Oh, I can’t believe she recorded this when she was 10.” You could say of the same to them: can you believe that you, not even 20, can do all of this?

I wanted to show that they are a little lost. I wanted to show that within themselves there was a mix of awareness and consciousness and unawareness and consciousness. Afterward, when they see the explosion, they just don’t get it.

Where do you feel that unawareness comes from? Is it because they’re young or is it because of our current Western culture, or a mix of both?

It’s a mix of both. The fact that they are very young is also important. I discovered this when I watched the finished film: although they are 18 or 20, I really see kids. I wasn’t aware of that when I was writing or shooting it. Their faces are so young.

Especially in the last stretch of the film, when the SWAT team comes in, you really get the sense that they are children; they are completely helpless. Was some of that imagery inspired by things that have happened in the U.S. in terms of police brutality and police violence?

No, not too much. I worked with an ex-cop who was on a SWAT team. He explained to me that with this type of geography, with eight floors, you can’t see everything, you don’t know how many people are there. So this is how they would handle that. What is quite violent in the film is that you see that from the point of view of the kids, not from the point of view of the police, which is what we would typically see in other films. Usually, we are outside the store and the Chief of Police is saying, “Okay, we’re going to start the operation.” All of that is totally off camera, and this is what makes it violent. I didn’t want to change my viewpoint to use parallel editing. I just wanted to stick with my viewpoint.

It’s like they’re being exterminated.

You can imagine that the government and police’s one mission is to stop the operation as soon as possible.

In contrast with this helplessness, there are also these bizarre moments when one of the young men occupying the mall leaves and goes out into the street, not once but twice—it shows an extreme arrogance. Those moments were so fascinating and eerie. Not just because that’s what those streets would look like in a state of emergency, but because there are several layers to his actions.

You use the right word—a kind of arrogance. He feels untouchable, original. They’ve done something crazy, so he can go out and have a cigarette. He can invite some poor people to go inside the store. It’s totally crazy, but it’s almost like these moments are so totally incredible that they bring some humanity to the movie.

Another component of the film is its commentary on how much of our life is mediated. We are being surveilled at all times. Everyone has a camera. In the film, the characters aren’t reveling in this, but they’re trying to understand these constantly mediated images. How do you see surveillance technology and the potential of always being filmed changing reality and changing film?

To me it’s one of the freakiest things in the world. It really is the end of freedom. I feel like it’s a personal aggression. And when I was talking about the feeling of tension, this is what I was talking about.