If she were part of a circus family, one might say she was meant to be the high-wire artist who for years had vertigo—until, suddenly, one day she found she could fly. Though she is Big John’s daughter, Anjelica Huston emerged, seemingly out of the blue, with an Academy Award for her sassy mafia don’s granddaughter in Prizzi’s Honor. Her first substantive role, the performance was assured, totally original. It shouldn’t have been a surprise. “There’s something wonderful about playing a black sheep,” she comments.

Aspects of Huston’s own life uncannily parallel those of Maerose, a woman doubly cloistered by her Italian Catholic heritage and her family’s illicit business. On her father’s side were the renowned Hustons, père et fils, and on her (Italian) mother’s there was success, talent, and tragedy. Reared on a remote estate in Ireland’s wild and mystical Galway, she attended convent school until the age of eleven, when her parents separated and she went with her mother to London. She felt profoundly out of place there, and her sense of dislocation was deepened by two subsequent traumatic events: at 15, A Walk with Love and Death, the acutely disappointing filmmaking experience with her father, and then the death of her mother a year and a half later in an automobile accident. Almost 20 years of study, struggle, and introspection would pass before she could stand in her own pink spotlight.

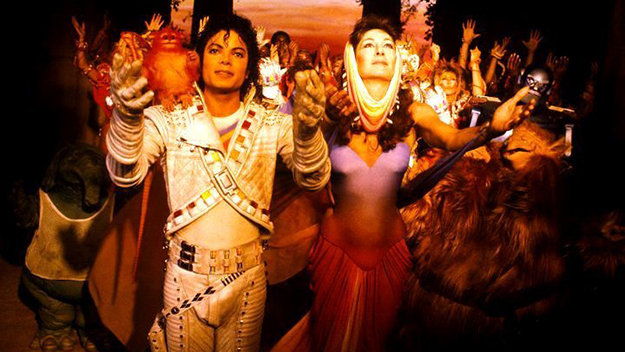

Since working for her father in Prizzi’s Honor, Anjelica has played a spidery witch transformed by Michael Jackson into a queen in Captain Eo, Francis Coppola’s 12-minute 3D laser film for Disney; a Vietnam-era Washington Post reporter in Coppola’s Gardens of Stone; and an Irish gentlewoman also in her father’s film, The Dead.

The Dead

The Dead is the concluding novella in James Joyce’s Dubliners collection, published in 1912. Set at an after-Christmas party, it is an ingeniously wrought parable of caution against certainty in all things, most particularly the covenant of love. Anjelica and Donal McCann, a major Irish theater actor, play Gretta and Gabriel Conroy, a bourgeois couple who bear the weight of Joyce’s morality tale.

Adapted for the screen by Tony Huston, Anjelica’s older brother, The Dead was a long-cherished dream come true for her father, who directed a large, ensemble cast of Irish actors.

“Our memories of Ireland are sweet but they are also haunting. Ireland is a terrible beauty. Making the movie was a sad experience, but we had to do it—as an ode to that time and those people, and to what Ireland meant to us. For all those reasons, it really came from the heart. Though the James Joyce story is set in another time, 1907, the characters felt familiar and the rooms on the set, with their ocher brown baseboard, were incredibly familiar.

The Dead

“To be with those actors for eight weeks was like living in Ireland, again. There’s a searing humanity to the Irish. I didn’t know many of them, and I was staggered at how good they were. I felt very much incorporated by them; there was no division, and the atmosphere on the set was so rich that it didn’t take a lot of work to remain in character. I thought of Gretta as a kind person. She has been married to this man for a long time and has a couple of children—like many women everywhere. It was nice that she came from Galway, like myself.

“I don’t think the dead boy, Michael Furey, was meant to represent her one true love. She loves Gabriel and her children very much, but she has held the memory of the boy inside of her for so long. It has to come out. She says, ‘I’ll never be that girl again,’ and it’s true for all of us: We know our hearts can never be broken in quite the same way, and death will never shock us as it does the first time. There was so much for me to draw on. I feel that way about my mother’s death.

“Gretta and Gabriel’s relationship will improve from this intimacy. They will look and speak differently to each other hereafter.”

When did you realize your father wasn’t like everybody else’s?

I can’t remember a particular instance in which I suddenly made that discovery. My first memories are from about age three. He never looked like anyone else’s father. He was taller and his voice was very distinctive. We were growing up in Ireland, and so the mere fact that my parents were Americans set them apart.

My mother was some 20 years younger than he, and I was very close with her. She was more beautiful than anyone else around, and he was larger than life. They were both somewhat larger than life, and our life was larger than life. There was a castle on our property in St. Clerans, an old Norman castle that was really ravishingly beautiful.

Gardens of Stone

Did you feel constrained by any of that?

Not really. As a child one accepts pretty much one’s circumstances, and I certainly didn’t have a bad time. I was, I think, the only girl in the convent school who didn’t get smacked for not knowing her catechism. I spoke French, was practically bilingual, and I was teacher’s pet.

Your father said that you and your grandfather share a unique quality: the ability to jump into and out of somebody’s skin. Do you sense that about yourself?

No, but having watched my grandfather—the first time was in Treasure of the Sierra Madre—I think it’s true of him. I thought of him as a little old grandpappy kind of figure until, years later, I saw him in Dodsworth. Then I realized the extent of his talent.

Here is a quote from your father: “Anjelica has a rare appreciation of things done with a certain amount of style. Those periods of my life where style was most evident she refers to most often.”

It’s true! Some of my best memories were watching my parents get dressed to go out in the evening. I remember sitting on the edge of the bathtub watching my mother put on her makeup. I loved the transformation. I loved watching her put on the Balenciaga and become breathtakingly beautiful, and it was much the same with my father. The smell of cologne, beautiful white, starched shirt fronts.

It wasn’t until my parents split up that I was even aware of money…and then I was terribly embarrassed by any reference to it. Around my father, the standard of living had been high. Only much later did I learn that Dad often lived way beyond his means. Yes, I admit I always fancied red carpets and chandeliers. In London, I envied the little girls who were dropped off at school in Bentleys.

Captain Eo

Maybe that’s why you enjoy playing all these fantastical characters in Fairy Tale Theater and Captain Eo. Even the don’s extravagant granddaughter, Maerose.

Well, I think of Maerose as a well-grounded girl, as someone very real who came from a situation in which she had to fight and pull her own weight. The part was so beautifully written. Maerose gets a full background, she doesn’t just appear as tarantulan. We see what she has gone through—held down, ostracized, punished. That’ll change you. We’re all products of our upbringing.

The part is very visual. When you’re creating a character, is the visual aspect important to you?

Very important. Of course, I start with myself for any character I play—investigate how I can adapt myself to the character. Maerose is a woman who has had to create herself, and she’s holding her head up. She’s on a fixed income from the family, but she has taste—an eye for color and for style. She’s into interior decorating.

Maerose at home is unlike, say, Samantha Davies, my character in Gardens of Stone. Maerose is someone who gets up in the morning, puts on the full stick, and stays that way. A lot of Italian women are like this. Not long ago I was part of a seminar that included Gina Lollobrigida. You can tell from looking at her that she gets up every morning, puts on her makeup, perfects her hair and nails—creates herself. It’s something many of the old-time movie stars had, and it’s very much Maerose. She has a knot in her heart, but she’s going to look and be her best. I think it shows a lot of self-respect. It’s the kind of thing that wins the war.

When did you have a say in her costumes?

Absolutely. My immediate instinct was to put her in the dark, widow colors of the Sicilian Italian—to contrast the black with bright, poster colors in such a way that they would sing out.

I was in the costume department on one of the first days of pre-production, trying on a dress that was black with a frilly taffeta piece that came over the shoulder and looped to the other side: a designer dress from the Fifties. I told Donfeld, our designer, that I thought it would be interesting to take off the ruffle and drape it in Scaparelli pink. (From the moment I first read Prizzi’s Honor I saw Maerose in Scaparelli pink and black.) Just then my father entered the room. He looked at me and the dress, and said, “Well, what do you think about making the ruffle in Scaparelli pink!” That was the moment I knew there was no separation in how we saw the character.

Prizzi’s Honor

When did you feel at one with Maerose?

There were moments that gave me great joy on that movie, moments that just came through me in such a way as to raise the hair on my arms and make me feel like a good instrument. And they were like gifts because they came from the outside. The first moment was in the “practice your meatballs” scene with Jack. I was seeking a particular frame of mind for Maerose, and as I looked around at some latticework, I saw two perfect ovals. Jack was behind one and my father was behind the other. I could literally look from one to the other, and use it for Maerose. Another time with the don, William Hickey, a great actor, I had wondered how he would deliver the stultifying line “You are flesh of my flesh, blood of my blood.” Well, when we did it for the camera, I walked in and kissed his ring. Then he stood up, did a little dance, and said, in a funny little voice, “You are flesh of my flesh, blood of my blood.” He did it with such joy, such effervescence, and such affection toward me that I completely understood who I was: I’m his little girl and he’s my grandpa who makes me laugh.

Did you ever tell him?

No. He knows what he does. He’s brilliant. When you work with an actor like that, there are just limitless possibilities. When I come home, I’m full of questions about what I did, and doubts, and it’s not particularly creative for another actor to hear that. That’s one reason I decided to live apart from Jack during the movie.

Jack acknowledged plenty of doubts on his part as well—not enough takes or feedback, and not the kind of relationship with your father he was used to having with directors, and expected to have with John.

My father didn’t have a lot of extraneous stuff going on when he was working, and that’s sometimes unsettling because you want to be cushioned a little. When he worked his mind was so streamlined. And also because of his age and health, he had to be economical with his time. Making Prizzi’s Honor was not a moment when Jack and I needed to hear each other’s problems, or take them to him.

It takes time to evolve such a relationship.

Yes, but we both understood it was the most constructive way to approach the work. When I decided to do the movie, my character dictated a lot of my attitude. I knew I wanted to be very concentrated and clear; to show up with my own power and keep my plumb line straight. The movie happened at just the right time. Acting class had given me a lot of confidence, but I knew I couldn’t take on anyone else’s problems.

Prizzi’s Honor

How did you manage to hold body and soul together until Prizzi’s Honor—trying to find yourself amid so many accomplished and famous people?

When I first came to New York, after my mother’s death, I wasn’t too interested in acting. I felt quite criticized and raw after A Walk with Love and Death. I decided to model for a while, but I wasn’t a traditional American type. For two solid years I worked only for Dick Avedon because no one else would book me. Then I went to Europe, and in Europe I got work. I came back, changed agencies from Ford to Wilhelmina, and never stopped working. Then I wanted a break, so I came to California for a year. It turned into three.

I started to become bored and fretful. I didn’t want to use my—for want of a better word—“contacts” because I didn’t want handouts. Mike Nichols wanted to test me for The Fortune, but I wouldn’t do it. A turning point came when Lee Grant asked me to be in a Strindberg play that she was directing with Maximillian Schell, Richard Jordan, and Carol Kane. We started rehearsals, and at a certain point she said, “You should go to acting school.”

In a critical spirit?

Yes. I was unwilling to give a full characterization, which she wanted, because I was trying to figure out my character. I was devastated. Then I thought about it seriously and decided that, whether or not she was right, I wanted to know what was right for me, and I began to study with Peggy Feury. She did nothing but reinforce me and give me confidence. She calmed me down a lot, helped me be less demanding of myself, and she was extremely kind—which is what I needed most. I was very insecure and apt to overstate in my performance.

The conclusion I drew was that I had an instinct for good writing, and that I sought honesty in the parts I played. Rather than go to acting class to find out what I didn’t know, I found out what I did know. Peggy changed my life. Everyone should have such a guardian angel.

After a while, little acting parts started to come up. Penny Marshall asked me to do a couple of Laverne and Shirleys; I worked as an extra in Frances; I had little bits in The Postman Always Rings Twice and Spinal Tap. I also have John Foreman to thank. A lot of people talk and there’s no action, but he offered me a sizable part in Ice Pirates. It was an entry.

Spinal Tap

Has your Oscar convinced you that you’re good?

Well, this business of the Oscar…you have to be a bit defensive about it. We all know it’s just insane to compare one actor to another. Still, you want it. A lot of it is tortuous—what you’re going to wear, and what you’re going to say. You know that whether or not you get it, there’ll be tears before bedtime. Too much fun at the fair.

With that foreknowledge, I had a wonderful time that night. After the Governor’s Ball we went to Dad’s hotel room. Everyone was a bit pissed off that he didn’t get it, but I wasn’t going to allow that to spoil my parade. I knew he and Jack would’ve preferred I win, rather than the flip. That was comforting.

I remembered Robert Towne going home in the limousine after Chinatown, hiding his Oscar in the wedge between the seats. I did not want to do that. I was going to enjoy the moment. And I did.

What did you like about Gardens of Stone?

Gardens of Stone expressed a woman’s feeling about men and war. That is what attracted me to it. I’ve heard it said that the film was pro-army and anti-war but I personally find that a contradiction in terms. I guess we all understand that armies must exist. The film took no sides; it was really quite original in that respect. It may have shown the soldier in a somewhat glorified light but it also showed the absurdity of the whole process. It certainly showed that people are people, affected by time and circumstance, despite their institutions’ allegiances.

How does that jive with Apocalypse Now?

It’s the flip side. I’d like to see them on a double bill. A time comes in all our lives where retrospect is not only inevitable but necessary, and it seems to me that history is very rapidly doubling up on itself at ever-greater speed. By 1990 we may be celebrating 1987 as a bygone era.

Gardens of Stone

Samantha, your character, is perhaps the first ordinary mortal you’ve played.

I liked that! I liked the character; she was a good girl, sweet and strong and full of heart. And I wanted to be able to say those things about War that she says—that it’s genocide. I love to work with Francis. Obviously, things were very hard on Gardens of Stone, and it’s a miracle he got through it. But he has the qualities I look to in a director. A director is the captain who draws together the forces. My father always tended to surround himself with familiar faces, and it’s very strong in Francis—that family thing where you’re all working together and there’s such excitement. You feel the man has an idea and knows where he’s going.

That doesn’t mean you have to report to the captain, but it does mean that if the rigging isn’t going up the way you’d quite like, you can speak to him and he’ll give you a key, perhaps the voice of the picture, as my father did on Prizzi—some little secret to get it up. It’s the gift, and the vision, and the power. It makes you want to please them more than anything in the world, and when you do you feel great.

How did you cope with your father’s illness?

I coped on a day-to-day basis. It was extremely painful to watch someone whose mind was so vital laid low by bodily matters. When I think of how many of us abuse our health and how he fought to survive, I become angry. I wish above all things that he could have had his full health on a daily basis.

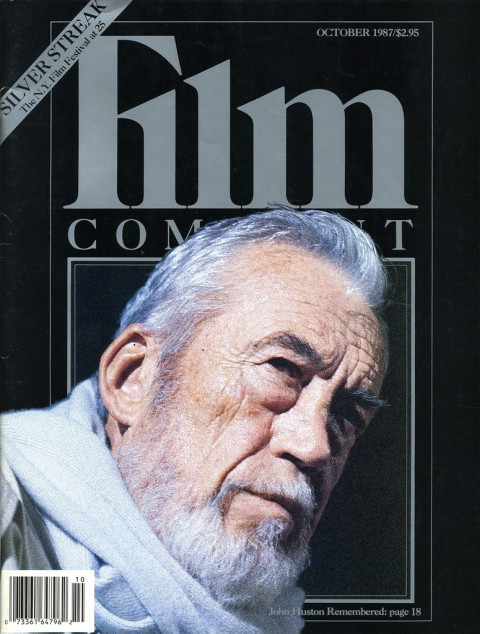

What is the main legacy your father leaves you?

A love of things beautiful and an attempt toward understanding rather than immediate judgement. One of the things I admired most about my father was that he liked you to know what you’re talking about; he didn’t suffer fools lightly. He liked a qualified statement, and I admired his search for that.