Interstellar begins more or less after the end. More or less, because the talking heads telling us about the end are evidently speaking from some later point in time, reminiscing about the doomed environment we are about to enter—an early signal that this movie will be a zone in which beginnings can never be presumed to precede endings. From what we can make out, civilization is smashed, in the wake of an apocalypse triggered by the effects of advanced technology. In a “post-Federal” Middle America, the surviving inhabitants cultivate cornfields as a last-ditch source of nourishment in the face of encroaching blights and dust storms that must soon render the Earth uninhabitable.

We become aware of lone individuals who may have it in them to redeem the lost world: Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), a former pilot who still dreams of space exploration, and his precocious young daughter, Murphy (Mackenzie Foy), who receives mysterious communications from what she believes to be a ghost or poltergeist. The signals from beyond are directing them toward a secret installation where scientists under the tutelage of a great astrophysicist (Michael Caine) work to perfect a means to escape from the dying Earth. The professor’s project requires sending Cooper, with a crew that includes the professor’s own daughter, Brand (Anne Hathaway), on a mission into another galaxy located somewhere in the vicinity of Saturn.

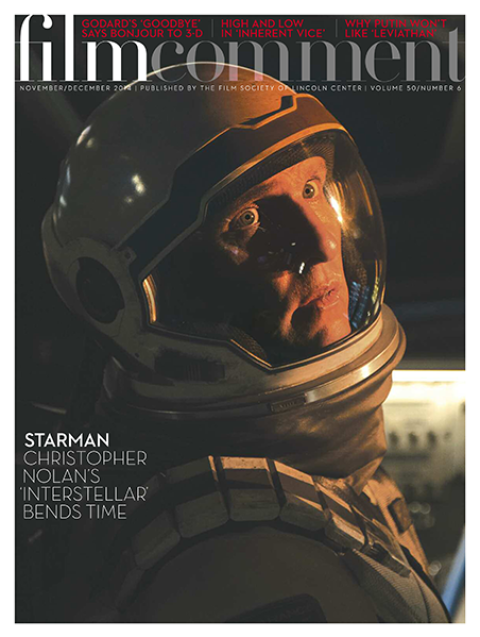

Yet as Cooper and his shipmates proceed into the farther reaches of their voyage—against a backdrop of spacecraft control panels and air hatches, moving at times through Kubrickian arcades of cosmic warp, alighting on worlds that are all mountainous waves or locked in ice—there is the deepening sense of approaching the limits of a livable human relation to space and time even while continuing by reflex to go through the motions of being human. They have reached the point where they can drop down from the spaceship onto a world where time passes at a different rate, and come back a few hours later to find out that they’ve been gone for 23 years. “I’m not afraid of death,” someone says, “I’m afraid of time.”

The whole movie comes to a stop for a moment with the blunt force of time’s horror and the insuperable barrier of human lifespan. We crosscut between parallel narratives and parallel galaxies, as the odds of bridging the abyss seem increasingly narrow. The arc of personal story—the drama of daughter’s abandonment by father evolving toward the drama of father’s rescue by daughter—is twined around the more elusive arc of wormhole physics with its promise of connections between points remote from each other in space and time.

Having set out to be a journey into what can hardly be depicted at all, Interstellar must find oblique ways of suggesting further imperceptible dimensions of the real. It is worth the journey to see what Nolan has constructed as a model of the unknowable. The end-of-the-world story changes into a beginning-of-the-world story, an optimistic paean to hidden human capabilities, holding out the possibility of a scarcely imaginable multidimensional future for the species—even if that future may require jettisoning much of what is supposed to be intrinsic to human identity.

The ghost story becomes a story of resurrection. Yet the ostensible optimism is underscored by a sustained note of mournful anxiety, with Dylan Thomas’s vibrant unconsoled threnody “Do not go gentle into that good night” repeatedly invoked. We are brought at last to an extraordinary transgalactic reunion at the brink of dissolution, an Einsteinian variant on the last scene of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. True to its obsession with recursive temporal arcs, Interstellar is a narrative that reveals itself not so much in the telling as in the playing back, as we make contact with an ending that was already the point of departure.