Internal Affairs

Bad Education extends the formal exploration of recent Pedro Almodóvar films like Flower of My Secret, All About My Mother, and Talk to Her, stories dealing with "identity crises" in the most extravagant terms. Almodóvar's comedies have always gone to dark extremes of farcical melodrama; they operate with a kind of acrobatic weightlessness, their characters resembling unstable chemical substances trapped in human containers, spilling out in foaming contents when shaken. They appear, too, to leak into one another and borrow each other's form.

I had not paid close attention to what Almodóvar was up to during what I call his “Hollywood” period: not that he “went Hollywood,” but the films that start with Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (88) didn’t much snare my attention and were so widely well-received that I felt sure there was something wrong with them. With Flower of My Secret (95), though, Almodóvar’s immense cunning hit home: a writer successful as someone else, under another name, writing books that in no way coincide with her emotional constitution, decides to write entirely different books, assuming an identity in every way opposed to her inauthentic “self’—every writer is someone else at heart. And, too, with Flower of My Secret begins a discourse on identity that reaches into the scientific or medical realm.

It has become entirely usual in recent years for AIDS to feature as a narrative element in Almodóvar’s films, and the nature of a retrovirus has some metaphorical bearing on the characters Almodóvar invents: they enact an infernal argument with themselves, a conflict about what is “me” and “not me.” The confusion of the self with another becomes literalized in the “theater” of organ donation in Flower of My Secret and the theater-that-becomes-real in All About My Mother (99); the latter film takes the internal oscillations of identity to bizarre extremes, wherein the father figure is, in one sense, also a mother, engendering a sequence of identical children.

Within the “secret” of All About My Mother we see an unfolding and a neutralization of class distinctions, of the bourgeois realm revealing a submerged history of subproletarian existence, the mother-become-pseudowhore, the patriarchal role feminized, the maternal role conflated with a sort of feminized patriarchy. Something else is also at work, in the intense physicality of Almodóvar’s people. They may suggest in general outline creatures out of Evelyn Waugh or Ronald Firbank, but their extreme vulnerability introduces modes of discomfort more readily associated with “realism”—one especially thinks of the Penelope Cruz character in All About My Mother, who, as a pregnant, HIV-positive nun, is doubly fragile, carrying a child that may be seropositive.

In Talk to Her (02), Almodóvar achieves what would appear to be the ultimate destination of the “me, not-me” conundrum: a film about characters who are technically dead, whom the narrative “keeps alive” in the same way that the nurse Benigno keeps the comatose Alicia alive; Benigno’s refusal to recognize that Alicia is “not Alicia”—like the stubborn actors in the organ donation videos of the earlier films who refuse to understand the difference between brain death and “life”—opens a space of infinite suggestion, where a life story can occur in a breath. This space is one the viewer apprehends viscerally, which is to say, Almodóvar brings us uncomfortably close to our own deaths. The self-abandoning risks his characters take by assuming the full consequence of their wishes are an excoriating commentary on the varicolored, one-dimensional conformity of ordinary modern life; even at the nadir of “the lower depths,” Almodóvar locates more authentic human will, more genuine feeling, than can ever be found in the bourgeois world. His work doesn’t despise that world; instead it tries to open it to deadened feeling, to indicate what is essential to life and to expose its empty formalities and discriminations.

Some kind of histrionic genius is at work in these acrostic narratives, which start from impossible premises and steadily raise the ante of unlikeliness; Almodóvar’s exaggerations have affinities to Molière as well as boulevard comedy, and emit the veracity of metaphors beyond the reach of logic. Almodóvar’s position is eminently sane and human—the permutations of identity, whether willful reinvention of gender, or Manuela’s deliberate return to a painful earlier version of herself in All About My Mother, or Victor’s drastic “rehabilitation” in pursuit of an immutable obsession in Live Flesh (97), are bracing assertions of existential freedom in the daily confrontation with necessity. Perhaps the most admirable figures in these films are those incredibly resilient, antic transvestites who invariably prove to be better “men” than the macho characters so often willing to use them for sexual relief.

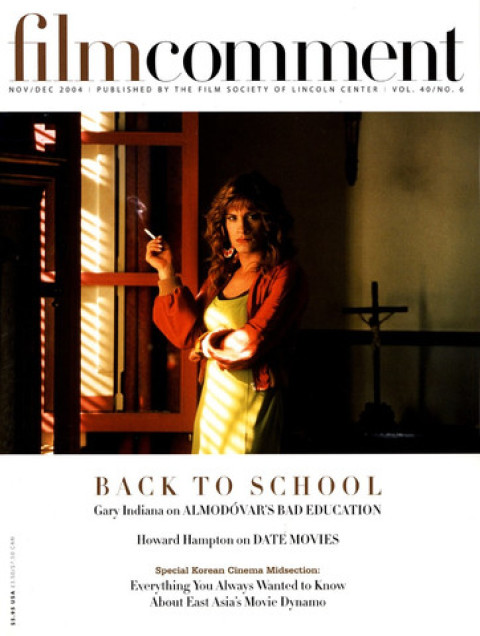

Bad Education (Pedro Almodóvar, 2004)

Almodóvar has recast the Spanish picaresque in contemporary terms, as Buñuel did in his later films. Bad Education has roots in The Saragossa Manuscript and similar epics of digression featuring stories within stories. Its main thread is the kind of interrupted tale the picaresque renders in pleats and fragments.

As schoolchildren, Enrique and Ignacio enjoyed a special friendship that ended when Father Manolo, infatuated with Ignacio, had Enrique expelled. The film opens as Enrique (Fele Martínez), now a successful film director, rummages through sensational news items looking for a usable story. A handsome youth appears in the office, none other than Ignacio (Gael García Bernal), whom Enrique hasn’t seen in 16 years. Ignacio has become an actor and prefers to be called Angel. He gives Enrique a story he’s written, “The Visit,” based on their experiences at school.

“The Visit” more or less faithfully mirrors the repressive environment of the school, the boys’ escapes to the local cinema, their clandestine bond, and the malignant attentions of Father Manolo (Daniel Giménez Cacho). Ignacio has also written of his later life as Zahara, a transvestite junkie attached to a burlesque company, reencountering Enrique as an anonymous trick and attempting to blackmail Father Manolo—who, with the help of another priest, manages to dispose of him.

Enrique wants to film the story. Ignacio insists on playing the role of Zahara. Enrique explains that Ignacio isn’t the right physical type. Ignacio angrily withdraws his offer of the story. Enrique then begins looking into the later parts of “The Visit” and learns that the Ignacio he knew at school is dead; “Angel” is Ignacio’s brother Juan.

Bad Education becomes progressively more complicated, as Angel sculpts himself into Zahara and becomes Enrique’s lover and star, maintaining the fiction that he is Ignacio; ultimately Father Manolo, now defrocked, with a family, reenters the story to reveal how Ignacio died.

Nothing here is at all what it seems. Bad Education is particularly unrewarding to synopsize, since its textures owe so much to the performances of Gael García Bernal, Francisco Boira as the “other” Ignacio, Lluís Homar, and Daniel Giménez Cacho; Bernal plays three remarkably distinct characters or personalities, with a smoldering conviction that verges on the psychotic.

Some of this film’s basic elements revisit Almodovar’s early works like Law of Desire (85), where there’s also a film director, an ambiguous love object, and a freight of transpersonal exchanges that defy the broad conventions of its narrative setup. As Enrique, Fele Martínez has a general resemblance to that earlier director, and a similarly persistent curiosity; he’s considerably more ruthless and is quick to sense Angel’s predatory nature, and, it must be said, Enrique’s personality reflects the artist in the ostensibly mature phase of egotism wherein life becomes the sacrificial material for creative work and only secondarily what is lived.

Enrique’s ego immunizes him against the abject and dreary trajectory “The Visit” has imagined for him as a fictional secondary character in Ignacio’s drama. If he allows Angel to manipulate him, this is entirely in the interests of his own project, while Angel’s purpose remains ambiguous. As director, Enrique holds all the cards, even if he doesn’t have all the puzzle pieces. Yet Bad Education’s central mystery is not his, nor is it the mystery of his creative process—though it does, miraculously, provide a guided tour of Almodóvar’s.

The mystery is this: what does Angel/Juan/Zahara want? Is he Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity? Bad Education may very well be The Revenger’s Tragedy, and a little bit All About Eve, but it’s a given that all Angel’s manipulation can accomplish is a film by Enrique, who will, in the course of making it, learn what really happened to Ignacio, which then becomes the revelatory climax of a film by Almodóvar.

Angel/Juan “becomes” Ignacio, “becomes” Zahara, and the question remains: why? To dissemble a crime or assimilate his victim? To accomplish his revenge on “Mr. Berenguer” (Lluís Homar), formerly Father Manolo? As Enrique’s lover, Angel completes a story broken in mid-sentence 16 years earlier, and arguably incarnates Ignacio, effects the gratification of someone else’s desire. His seduction of Berenguer, likewise, rewrites the incomplete narrative of Ignacio and Father Manolo. Angel’s impersonation has the aura of a criminal act, and he assumes it, it appears, as an essential ingredient of an actual crime.

Bad Education answers “why” with further equivocation. Angel inhabits the film like some process of oxidation. He is its Iago, the pure embodiment of amoral desire. In this he seems hardly different from Ignacio after Ignacio has become Zahara. The victimizer Father Manolo becomes the victim Berenguer; ultimately, the wreckage of several multiple identities has piled up, so to speak, on the set of The Visit. In the end, no one is entirely to blame for the nasty lessons life has taught him, and everyone is trapped in the institutional madness of church, state, capitalism, and cinema.

Gary Indiana is the author of seven novels, two collections of short stories, and several books.